A.J. Muste’s gives his analysis of the crisis over John L. Lewis’ leadership in what was, for generations. the largest and most important working class organization in the United States.

‘The Crisis in the Miners’ Union’ by A.J. Muste from Labor Age. Vol. 19 No. 3. March, 1930.

WITHOUT blast of trumpets, with very little definite warning, without a word of comment as we go to press from official American Federation of Labor circles, comes an event that may prove to be of the most profound importance to that organization and to the entire course of the Labor Movement in the United States. Backed by the miners of District 12, United Mine Workers of America, Illinois, a call has been issued by 22 prominent miners, most of them noted for their progressivism, for a convention to be held in Springfield, Illinois, on March 10 “to establish an international organization of the United Mine Workers of America.”

The call goes on to state that the further purpose of the forthcoming convention is “to adopt an international constitution of the United Mine Workers that will place the control of the organization in the hands of the rank and file by restoring home rule to the districts to elect international officials in accordance with the provisions of the constitution to be adopted, and to adopt ways and means to accomplish the complete reorganization of the U. M. W. of A. and “to unionize the unorganized coal fields and stabilize the coal industry.”

What has led up to this momentous decision of the Illinois district and such miners’ leaders as Alexander Howat, John Brophy, John H. Walker, Adolph Germer, to smash the Lewis regime and reorganize the United Mine Workers? Who are the people, what are the forces involved in the situation? What is likely to be the outcome?

The Coal Industry

The bituminous coal industry in the United States suffers from the disease of “over development.” The industry has always been a highly competitive one because it is a comparatively simple matter to open up a coal mine, and because there is a great demand for coal at certain seasons of the year, tempting operators to open up mines in order to take advantage of the high prices offered when demand temporarily outruns supply. These mines then are wholly or partly idle when demand drops. For the miners this means, of course, that large numbers of them are brought to coal camps, settle down, acquire homes and certain habits of living and working not easily broken, and then by the thousands find themselves altogether out of work when mines close down, or on short time in such mines as remain open.

The war greatly stimulated the demand for coal for various reasons. John L. Lewis came into the presidency of the United Mine Workers of America in 191 9 when the boom was still on. Even after the war boom was over new mines were opened up and machinery was introduced at a rapid rate, so that the mine capacity increased from 672,000,000 tons in 1914 to 796,500,000 in 1920, and again to 824,000,000 in 1925. Incidentally, the proportion of bituminous coal mined by undercutting machines advanced from 25 per cent of the total in 1900 to over 50 per cent in 191 3, reaching 72 per cent in 1927. Since the amount of bituminous coal the country can consume is about 50,000,000 tons annually, the capacity is over 300,000,000 tons in excess of what the country can consume.

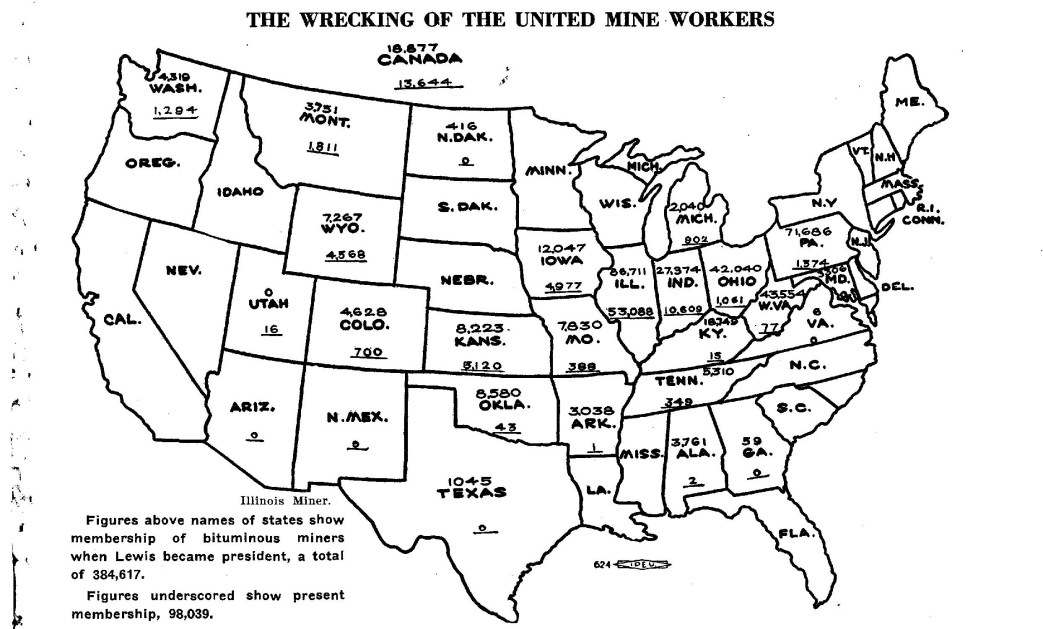

This situation must not be lost sight of by anyone who wishes to make a fair evaluation of men and policies in the miners’ union during the past decade. It is a situation with which any new leadership the United Mine Workers may develop will have to reckon. It means that there were more miners than could profitably be employed, and that there was bound, under the best circumstances, to be unemployment on a considerable scale among them. Under such conditions it would have been difficult for anyone to hold the miners’ union intact and no one could possibly have kept the membership up to its peak. To illustrate, even in Illinois where the mines are still practically 100 per cent organized, the membership is down to about 53,000 from a peak of something like 90,000.

The Lewis Policy

What policies were suitable to meet such a condition, and what did President Lewis do about them? In the first place, it seems obvious that something needed to be done to stabilize the industry, to prevent the constant opening up of new mines when the industry was already suffering from over development. Nationalization of the mines was proposed immediately after the war by a number of economists as a solution. The miners in convention assembled appointed a committee to study the subject and to prepare a report for study by the miners on the basis of which a definite program for the control of the industry might be adopted at a subsequent convention. The committee included such men as Chris Golden, at that time President of District 9, and John Brophy, at that time President of District 2. The committee prepared its preliminary report for circulation among the miners. Then Lewis sabotaged the work of the committee and prevented the miners’ convention from dealing seriously and intelligently with the problem. It is quite conceivable, of course, that no measure for nationalization of mines could have been passed in this country. However, if the full force of the miners’ union had been put back of an agitation for nationalization, it is possible that either the operators or the government or a combination of the two agencies would have taken some serious steps to stop expansion and to stabilize the industry. With the nationalization movement killed and no substitute plan offered, nothing needed to be done and nothing was done. Government and operators could hardly be expected to be wildly enthusiastic about a miners’ union with 500,000 members, and the union might slowly and surely be bled to death in an industry suffering from chronic overexpansion and unemployment.

Moreover, the expansion during the war and the years following took place mainly in new districts, such as West Virginia, Kentucky and Alabama. There were excellent seams in those states. It was easier to introduce up to date machinery and methods in new mines. There was a supply of cheap labor in the hills and on the farms of the South to draw from people with no union experience. The union, on the other hand, was strong, especially in the so-called Central Competitive Field, including Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and Pennsylvania. In these states wages were high and conditions good. It seems obvious, again, that sound union strategy demanded an intensive effort to organize these nonunion strongholds, since otherwise wages and conditions must inevitably come down in the union districts, if indeed the industry was not to be entirely crippled in the latter by the competition from the new and unorganized fields. How did the United Mine Workers under the Lewis leadership handle this problem?

It cannot be said that no effort to organize the non-union fields was made. Lewis can point, as can other A. F. of L. unions, to large sums of money spent in the South. Some terrific bloody battles for unionism were fought in the coal fields in these states. But in the first place there were some apparently inexcusable betrayals of non-union miners when they heeded the call of the organization and came out on strike. Thus about seven years ago John Brophy and Powers Hapgood organized the non-union field in Southern Pennsylvania. By the thousands the men came out on strike in response to Lewis’ summons, along with the previously organized miners of the county. Then the United Mine Workers made a settlement for the previously organized miners which left out the Somerset County men. Presently the International ceased to give strike relief to these men, who still fought valiantly on, although under the settlement union miners were at work in other sections, for the same coal companies against which they were still striking. District 2 itself was so far as possible discouraged by the henchmen of the International union from helping the strikers. A general cannot often leave soldiers in the lurch like that, whether with or without cause, and still retain any power to carry them with him into battle.

Secondly, far too large a percentage of the organizers sent into non-union fields were chair-warmers and errand boys for the International “machine” who perhaps were not expected to organize, and in any case did not.

Thirdly, when a couple of years ago the so-called Jacksonville agreement expired, when the union had been completely driven out of the southern fields and when there was a big differential in wages between the union and the non-union fields, Lewis adopted the strategy of insisting that the wage level in the union fields must be maintained at any cost, even in mines where machinery had been introduced and miners could make more than the Jacksonville scale called for, even if piece rates were cut. The result was an utterly disastrous, prolonged strike which pretty nearly wiped out the union in Pennsylvania, Indiana and Ohio. The Illinois district saved itself only by making a separate agreement.

The upshot in brief is this: When Lewis became president of the organization, fully 70 per cent of the bituminous coal mined in the country was turned out by union men, less than 30 by non-union. Today the proportions are reversed.

Killing The Soul of a Union

Lewis sabotaged the nationalization program for the stabilization of the industry and failed to provide a substitute. He made no adequate effort to organize the non-union fields. There is a third count in the indictment, possibly the most serious of all. Under the best leadership the United Mine Workers would have been compelled after the war boom to beat a retreat at certain points. In such a period a union needs a calm, unselfish, utterly devoted, idealistic general, who will toil and suffer and struggle with his men. In other words, its soul must be kept alive. And though it be true that an army marches on its stomach, there have been generals who could make it march on its soul when stomachs were empty. What sort of generalship did Lewis provide the miners?

He permitted his salary to be raised at the last convention while literally thousands of miners were on the edge of starvation. He permitted, if he did not abet, a regime of corruption through the padding of expense accounts, for example. He fought practically every expression of progressivism or radicalism among the miners. He caused the democracy of the miners’ conventions to vanish; debates were settled by slugging. He eliminated by ruthless methods anyone who was able to challenge his leadership or who ventured to differ from him on policy. Alexander Howat, John Brophy, John Walker, Bob Harlan, Powers Hapgood and many others were attacked. Brophy charged that the election for the presidency was stolen from him by Lewis, and the issue was never seriously tried in convention. Lewis actually undertook to persecute Brookwood and was instrumental in inducing the American Federation of Labor to attack this labor college because some members of the United Mine Workers who had graduated from Brookwood had the audacity to work and vote for Brophy instead of Lewis in that election. International organizers were used to carry on “political” activities for the administration in organized self-governing districts, instead of promoting the union in non-union territory . Contrary to the constitution, the regularly elected officers of supposedly self-governing districts were replaced by provisional governments composed of personal henchmen of the international president. It was the fact that Lewis attempted to do the same thing in the Illinois district recently that caused the movement to unseat him and to reorganize the U.M.W. on a democratic basis, to take definite form. The officers of the Illinois district went to court and secured an injunction forbidding Lewis to interfere with their administration of the district.

The Forces in The Field

What are the forces and personalities to be reckoned with as the decisive conflict of March 10 approaches? On the one hand is President Lewis, a fighter, who in the past has walked over every opponent who has dared to stand in his way. With him stands his official family, the present (or must we say former) international administration of the U.M.W. of A. There is as yet no indication of a break in their ranks. Have these generals any supporters back of them? So far as the bituminous fields go, indications are that they can count on little, if any, support from Illinois or Kansas. The official family of the Illinois district has signed the call for the Springfield convention. They may not be able to carry all the locals with them, but there are no indications that Lewis will be able to carry any considerable number with him. Alexander Howat, president of the Kansas district, is also a signer of the call. But Illinois and Kansas between them have over 56,000 of the 98,000 dues-paying bituminous miners left in the U.M.W. There is a history of anti-Lewisism in Canada, and for a number of reasons it is doubtful whether Lewis can count on much support from that district, which has 13,644 members. Most competent observers question whether Lewis can count on much support from the 10,000 miners in the Mountain and Pacific Coast states.

So far the anthracite miners have not given any clear indication of revolt. Nor is it apparent that any strenuous effort is being made by the bituminous miners to induce them to do so. The anthracite districts may stand by the Lewis administration and thus he may have a union left in that branch of the industry. This would not necessarily weaken in any appreciable degree, however, the chances of success of the independent movement among the soft coal miners. In fact, it might in some measure strengthen it. The two branches of the industry do not work for the same markets. The history of the union has been one of bituminous helping the anthracite rather than vice-versa. The bituminous miners have always in normal times constituted the great majority of the membership. The contract of the anthracite districts expires at the end of August, and conceivably the bituminous miners might be better off if they did not have to add the renewal of that contract to their other worries. Besides, the anthracite miners have never had the check-off and they are by no means as sure a source of income as the bituminous men.

On the other side stand the forces which have now assumed the responsibility for seeking to end the Lewis regime and rebuild a union for the soft coal miners. Chief among them, as already indicated, is the Illinois district. The administration of that district during the past decade has certainly not been altogether above reproach. When all allowances are made, however, it has the prestige of having a practically 100 per cent organization of the miners in the state—53,000 dues-paying members, a contract with the operators which still has a couple of years to run, a fighting tradition, a solvent and functioning district organization. There is a fair chance that now having given a decisive lead, the officers of the district may be able to carry the overwhelming majority of their membership with them. There is the possible support from other bituminous districts, as already suggested. There is the support of such outstanding progressive union leaders as Alexander Howat, John Brophy and Adolph Germer. Special mention may be made of John H. Walker as a signer of the call for the Springfield convention. That despite his presidency of the Illinois State Federation of Labor and his close relations in recent years with the official A.F. of L. family, Walker, who was at one time president of the Illinois district and a Socialist, has now allied himself with the anti-Lewis forces, is an event of considerable significance.

Reference may be made in passing to a figure whose signature is not attached to the convention call, namely, Frank Farrington, predecessor of Harry Fishwick as president of the Illinois district. Farrington was at one time a bitter enemy of Lewis but subsequently patched up a truce with him. It will be remembered also that a few years ago while president of the Illinois district, he signed a contract to become an employe of the great Peabody Coal Corporation. He went to Europe as president of District 12, expecting to resign and assume the position with the Peabodys on his return. During his absence Lewis secured a letter written by Farrington which revealed the existence of his contract with the Peabodys. It is said that Lewis tricked Farrington into making this contract, and that Farrington did practically no work for the Peabody interests during the three years which that contract ran. Certain it is that in recent months Farrington has been among the foremost of those attacking Lewis and has given great impetus by his writings to the campaign waged by the Illinois Miner, the official organ of District 12. Obviously, this is a complex situation, some of the phases of which are probably still unrevealed. Many observers hold, however, that it would have led to confusion and misunderstanding if Farrington had been among the signers of the call, that it might have divided forces in the Illinois district, and that if he is genuinely desirous of serving the rank and file of the miners, an opportunity to demonstrate that may possibly come during some future time.

What of the Communists? Their recent strike in Illinois was a total failure. It is not apparent that they need to be reckoned with seriously in the miners situation today, whatever may have been the case in the past or may be the case at some future date.

What of the A. F. of L.? For them this situation is pregnant with serious, if not disastrous, possibilities. If Lewis fights the present move and declares its promoters and following outlaws, the A. F. of L. on the basis of its traditional policy seems bound to support Lewis, and that means the possibility of a miners’ union outside the A. F. of L. fold. Presumably, interested parties are conferring behind the scenes. There are indications, however, that all the A. F. of L. can do for the present is to stand by and watch developments. When the Illinois district wired to the A. F. of L. convention at Toronto in October an offer to open its books to competent certified accountants if Lewis would do the same, the Illinois officers to resign if corruption were proved by the examination, and Lewis to do the same, the communication was quietly and very firmly ignored. Efforts which have presumably been exerted to prevent an open break and the calling of a convention in defiance of Lewis, have quite obviously come to naught. This situation can do more to the A. F. of L. than the A. F. of L. can do to it.

What of the coal operators, particularly in Illinois? They have a contract in the Illinois district which still has a couple of years to run. They are no better and no worse probably than coal operators generally and might break a contract, which would doubtless cause much embarrassment to the Illinois district. The chances appear to be that this will not occur. It is possible that by this time a good many coal operators have come to the same conclusion that certain leaders of the Ladies’ Garment industry reached not long ago, namely, that it is better to have a union and a stable industry than no union and anarchy. In any event the Illinois miners have a long tradition of militant unionism, and the operators probably shrewdly calculate that if they attempted to abolish the union, the result would probably be hell and not peace.

Possibilities for The Future

What are the possibilities for the future? They appear to shape up as follows:

1. The officials of the Illinois district may patch up an agreement with Lewis before the final break comes. This sounds weird after all they have said about Lewis in the Illinois Miner in recent weeks. Stranger things than this have happened, however. Yet it is unlikely. It is improbable that the progressives who signed the call for the Springfield convention did so without obtaining some guarantee that they were not going in for a sham battle or being led to slaughter in a tragic farce. What is much more to the point, it is highly improbable that the Illinois district officials could control their own rank and file if after all that has been said and done, they made a weak peace.

2. Lewis may take the anthracite and leave the insurgents the job of organizing the bituminous industry, the A. F. of L. chartering two unions for the coal industry—one to have jurisdiction in the anthracite and the other in the bituminous fields. The chances of this happening are likewise not very good. It would be unlike Lewis to give ground in this way; and it is hard to see how he could have any assurance of being able to retain his control in the anthracite once he is compelled to relinquish the larger part of the industry.

3. Lewis may, with some face-saving gestures, practically admit defeat. If some fairly important position were available for him in the Labor Movement, in business or in politics, this might happen. The difficulty in the way of this solution is that if he is virtually forced to retire from the miners’ union, he is in large measure a discredited man, and the chances of an important position being open under the circumstances seem slight.

4. Lewis may fight back, the A. F. of L. may back him up, and he may succeed in defeating the insurgents and retaining his hold on the U.M.W. This would also involve his taking control of the Illinois district. It is difficult to conceive of this happening* after what has already transpired, without a knock-down and drag-out fight in Illinois, which would wreck that district. There is not much in past experience to encourage the hope that Lewis might lead in an effective organization of the non-union fields, particularly if now the Illinois district is also wiped out. In other words, this would probably mean the wiping out of the union in the bituminous coal industry altogether, paving the way for company unionism in that basic industry also.

5. The outcome may be in the nature of a draw. For example, the insurgents may succeed in ousting Lewis only after a long continued battle and before the fight is over the Illinois district may be seriously weakened or wrecked, and the insurgents may find the job of organizing the nonunion fields impossible under the conditions. In this case also the miners’ union will eventually be wiped out and the way prepared for company unionism in the industry.

6. The outcome may be clear victory for the insurgents, with Lewis put out, the Illinois district left intact, and a vigorous organization set up to carry the campaign into nonunion territory.

If the insurgents achieve their aim, either because Lewis eliminates himself, or because they defeat him, then there is an excellent chance that a progressive, fighting, democratic, clean, intelligent industrial union may emerge in this great basic industry. As has already been suggested, the industry has gotten to the point where it may have to have a union to stabilize it. Intelligent leadership could avail itself of that advantage. In any case, however, the task of rallying the miners to unionism in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, etc., is a stupendous one. A union which undertakes it must have a fighting soul. It must be able to command the services of its idealistic spirits, and it must be able to enlist the confidence of the rank and file. Only a clean, progressive union can do that. Circumstances will compel the reorganized union to be that kind of a union, at least for some time to come.

Should this kind of a miners’ union come into existence, the chances are immensely increased that an organizing movement in certain other basic industries such as automobiles, steel, textiles, etc., would get under way. These unions would undoubtedly be tillable to achieve their ends under a policy of non-partisan political action, and would strive to join with others in launching a labor party. They would need a progressive workers education movement and would undertake to promote it. The C.P.L.A. program would have become the program of a mass movement.

If the reorganization of the miners’ union comes as a result of Lewis peacefully eliminating himself so that the A. F. of L. will not be confronted with the necessity of ruling on a question of “dual unionism/’ then unquestionably the reorganized miners’ union will be within the A. F. of L. and may contribute to the reinvigoration and transformation of that organization.

Problem for A. F. of L.

If the reorganization of the miners’ union comes as a result of a break away from and victory over Lewis, with Lewis declaring the insurgents outlaws, the A. F. of L., as has already been suggested, will almost certainly line up with Lewis. It is by no means certain that this would be a fatal handicap to the movement. “Dual unionism” in the sense of a movement which is built upon a theory or ism, and which seeks to break down existing unions, has not had much success in the United States. But “independent unions” which were not built primarily on a theory or ism and did not seek to destroy existing unions but simply undertook to meet the need for organization on the part of a group of workers who had been betrayed or were not being effectively served by an A. F. of L. union, have survived and flourished in the United States.

For the A. F. of L. such a development might have most serious consequences. Suppose that to the Railroad Brotherhoods, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers, and some smaller independent organizations, a big miners’ union were added, and to these presently unions in some of the other basic industries. If the A. F. of L. proceeded to bar them from affiliation, it seems certain that they would be forced to federate among themselves for certain purposes. Could the A. F. of L. retain its present affiliations intact in such a case? In fact, some important decisions involving these issues may have to be taken very soon. Suppose the reorganized union gets under way and is barred from the A. F. of L. at the insistence of the present U.M.W. officialdom, what is to become of the Illinois Federation of Labor, with the Illinois district of the miners constituting perhaps one-half or more of its strength, and with the president of that federation, John H. Walker, among the promoters of the “dual” union? What position is the Chicago Federation of Labor going to take in the face of such a development?

Whatever be the outcome of the convention, which opens at noon of March jo in Springfield, Illinois, it will make history for weal or woe for the American Labor Movement. It is well in any case that the Illinois district decided not to stall or temporize. To postpone the decision of the issues between it and John L. Lewis would have meant only confusion and distress for the miners. It has assumed grave responsibilities for which history and the workers of America will hold it accountable. A union in which the rank and file can believe, an honest, clean, democratic, fighting, progressive union for miners is desperately needed. The men and women who fought and died in the past to build the United Mine Workers call for it. The men who now work in the mines for starvation wages or walk the streets without jobs call for it. May the courage, the intelligence, the honesty to answer that call be forthcoming.

—-

Since this article was written John L. Lewis and his Executive Board, issued their own convention call to convene at Indianapolis, Ind., on the same day as that of the Illinois convention, March 10.

At the same time John L. Lewis called upon President Green to ask John H. Walker, President of the Illinois Federation of Labor, and one of the signatories of the Illinois Convention Call, either to withdraw his signature, or failing that, for President Green to revoke the charter of the Illinois Federation of Labor. This brings a new development into this complex situation.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n03-Mar-1930-Labor-Age.pdf