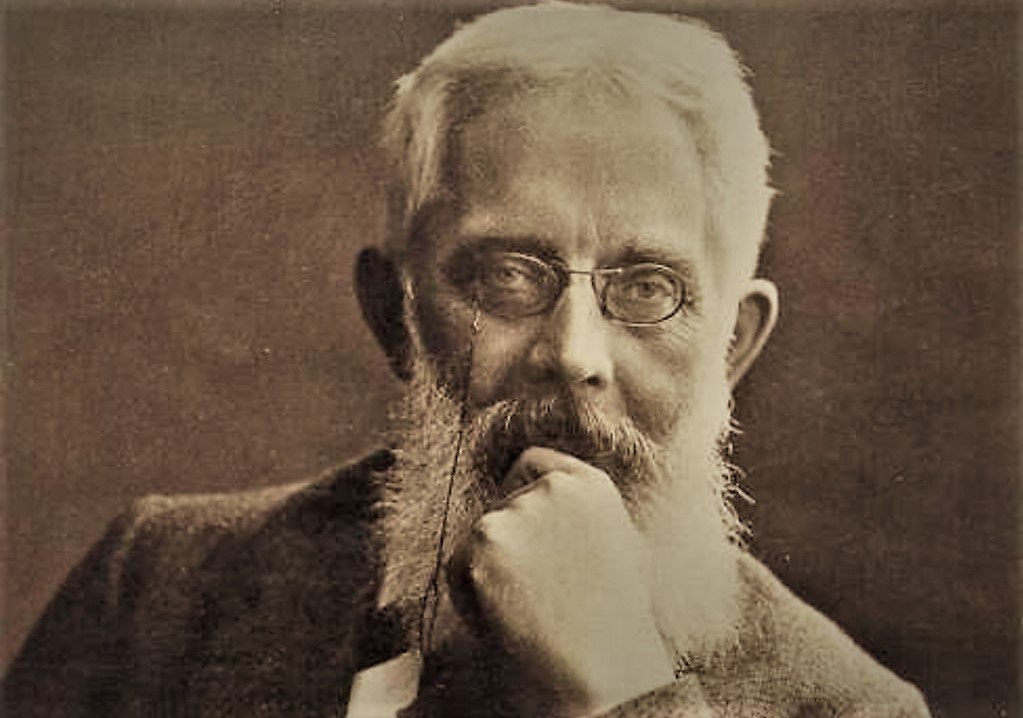

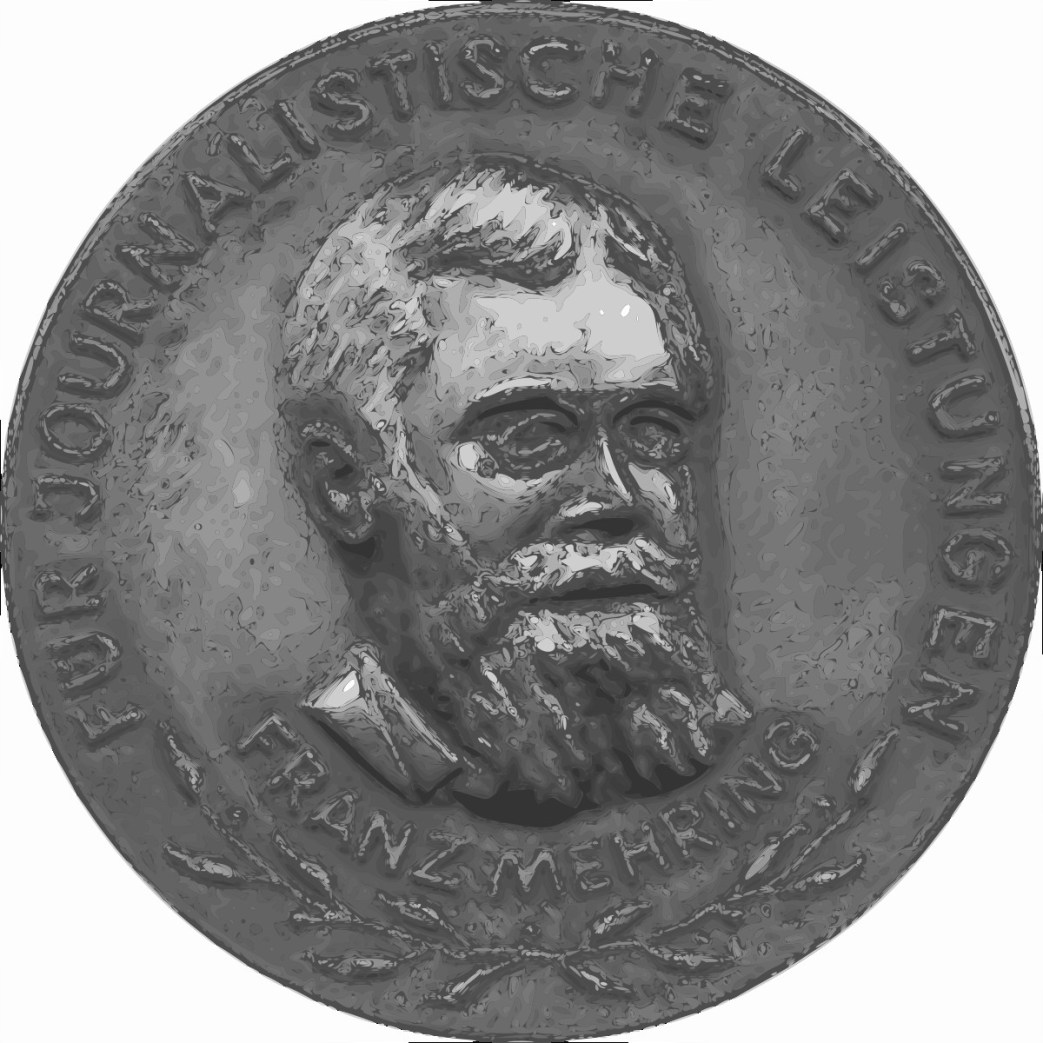

The life and work of the great German revolutionary on his death in 1919 at 72 by John Brahtin, a stalwart of the Cleveland left-wing, unionist arrested for sedition during the War, original member of the Communist Party in 1919, later to be expelled in 1929 as a Left Oppositionist when he helped to found the Communist League.

‘Franz Mehring’ by John Brahtin from Ohio Socialist. Nos. 61 & 62. March 26 & April 2, 1919.

At a time when the revolution in Germany needs its guiding spirits, clear thinking and far-sighted leaders most the unseen hand of fate takes them away, one after another.

In the course of the war, the overwhelming majority of the German Genossen went over to the imperialistic German government and declared that the integrity of the capitalistic fatherland is more sacred and stands higher than the struggle of the working class against its exploiters, the instigators of the war which threatened the fatherland. At that time a group of members of the official Social-Democracy broke away from that organization and launched a new one, under the name of “Spartacus.” They set to work against the deadly doctrines of class truce (Burgfrieden) advocated by the majority of the German party. For that purpose the Spartacides began to publish a new magazine “The Internationale.” The outstanding personalities grouped around that new publication, were, the old veteran of the German party–Franz Mehring and Rosa Luxemburg, H. Strobel, A. Thalheimer and Klara Zetkin. The hatred of the government Socialists against their adversaries went so far that they did not stop short even at spying and denunciations. They pointed out to the gendarmes and military authorities, who were the guilty ones. The group “Internationale” was easily rounded up and put behind prison bars.

Governments with their spy squads always think it possible to subdue any mass movement by the imprisonment of its leading individuals. The German government was not an exception, although it knew by experience, that such measures are ineffective. The severe persecutions by the government, supported by the kaiser’s Socialists, resulted in the suppression of the magazine “Die Internationale” after the appearance of its first issue. The German rebels, however, undertook other means of carrying on the combat. Among them was the old veteran, Franz Mehring, who during the exception law period watched the Socialist activities from outside and then, convinced of the justice of their cause, joined them.

A news dispatch, about a month ago, announced the death of Franz Mehring. Through the death of Franz Mehring the Spartacides lost from their tanks the oldest (he was 72 years of age) and brightest head.

The personal history of many of the veterans of the German Socialist movement is closely connected with the whole movement and cannot be described separately and apart from it, and thus it is true in regard to Mehring. He joined the German Social Democracy, not through economic necessity and pressure, but through fundamental understanding of the Marxian theory of economics, history and philosophy. After his graduation from the university, Mehring became a bourgeois journalist and many times joined issues with Socialists on the theoretical field. Nevertheless, he always sided with the oppressed on the grounds of justice. The horizon of the bourgeois justice is too narrow for a broad-minded man. Mehring strenuously strove to penetrate into the essence of things. Bourgeois philosophy interpreted the historical phenomena insufficiently and unexplicitly to him. To gain inside information about socialism he spent many nights in spirited discussions with the senior Liebknecht and August Bebel. It may be accredited to them that Mehring was converted to socialism and became one of its sincerest exponents and advocates. When joining the Socialist movement he was already a well-grounded Marxist. He did not join the movement to study it, but to use his broad and deep knowledge of human society to bring about the realization of the ideal of socialism. To this great ideal he remained faithful all the balance of his life.

To make up for his former attacks on socialism, Mehring set to write and publish on the origin and growth of modern Marxian socialism; he spread the conception of Marxism as a theory of social life.

Mehring’s Writings.

After the appearance of his first book, “Die Lessing-Legende,” a history and critique of Prussian despotism and classical literature, he established a reputation as a Marxian scholar. “Die Lessing-Legende” is a small book of minor importance to the average reader, although it is highly valuable to the student of social development. Mehring’s life’s work is, “Die Geschichte der Deutschen Sozialdemokratie,” (The History of the German Social Democracy) in four large volumes. This is such a wonderfully clear and scholarly work that there is no Socialist movement in the he world that has anything to compare with it. All other writers in the Socialist movement are dipping their information from this which shows no sign of exhaustion. The first volume of that great work traces the doctrines of Utopian Socialists before Marx, and shows how scientific socialism developed gradually toward its present completeness.

It prove that industrial development and the growth of the economic classes creates the necessity of clear comprehension of the task before the newly developing working class. We find the Utopian Socialists elaborating schemes about how to abolish the evils in contemporary society. Some of them go to great extent in working out the economic theory; others work on history and still others, on philosophy. New conceptions in the various fields of social science and practice come from various countries. Each one of these falls short in their own special area because they endeavor to separate these experiences from each other and do not take them as a unified whole. The practical schemes of these Utopians, applied to real life’s practice, appear to be entirely impractical. Meeting with failure they invent something new, only to fail again at the first trial. At last the working class discovers its real apostle and interpreter of society and its achievements from the economic standpoint, who unites economics, history and philosophy and proves their unity. That is Marx.

But Marx’s doctrine is outlined in highly scientific terms and requires much previous training of the mind to understand it. With incomparable clearness Mehring shows the sources from which Marxism originated. It did not come from the blue air, ready made, but took amply from the achievements of the French Socialists and historians, English economists and d from the industrial status of that country; it took much, but very critically, from the classical German philosophy of Hegel and Feuerbach. Knowledge of the historical development of modern socialism eliminates the cant saying that socialism is “made in Germany” and therefor will not fit the different conditions of the different countries, and that’s why it should be opposed when it appears in other countries. Mehring in his great work proves that socialism is not the inheritance of one country or of the working class of a certain country. Socialism, according to Mehring, is the last word in modern science. Science is not national but international, and so, also, is socialism. Marxism is not a static but a dynamic theory, it interprets social phenomena not as it stands at present but tells how it became what it is. And so we find in the first volume not only the beginnings of socialism in Germany but in all industrial countries in Europe, particularly France and England.

The Exception Laws.

Establishing the Marxian theory and its outcome, Mehring proceeds to show its special application and further development in Germany. The theoretical struggle between Lassalleans and Marxists is thoroughly discussed. Especially interesting is the narrative on the exception laws in Germany against Socialists, invoked by Bismark and their utter failure. The growth of the revolutionary spirit was the cause of Bismarck’s demanding such laws. With them he expected to destroy the revolutionary movement of the German workers. The impotence of these stringent laws to stop the growth of the German working class movement, forced Bismarck to ask for repeal of these laws. They were in n force in Germany for twelve years, from 1878-1890. In spite of the drastic action of the police and gendarmerie, the German workers marched triumphantly on shows how the organizations of the German workers multiplied, how education became always more broader and deeper and how the vote for the Socialist candidates to Reichstag always increased. When it was impossible to publish Socialist matter inside of Germany it was published outside–in Switzerland, Belgium and England and smuggled across the German border in hundreds of thousands of copies and spread broadcast.

The last volume of Mehring’s work has especial interest for us in America, now, that our Republican statesmen are endeavoring to practice in this country those persecutions against Socialists that monarchial Germany, through Bismarck, tried to do 30 years ago. The monarchy of Germany failed. Will the republic of America succeed? Industrial Germany of that epoch was in state of its development, the working class, small, numerically inferior to the other classes; the U.S. is at the climax of its industrial development, its working class outnumbers all the rest of its population. The of the German working class made ineffective the exception laws in that country; the growth of the working class consciousness in this country will accomplish the same here. The numbers are here already.

Edits Marx and Engel’s Writings.

The second great work that Mehring undertook to accomplish, was the editing, and publishing of the unpublished manuscripts of Marx and Engels. This task Mehring fulfilled in a masterful way. The Socialist Internationale has before it all that Marx wrote. Under the general title, “Aus Dem Literarischen Nachlass,” Mehring gathered and published all those writings, which Marx and Engels did not live long enough to see in print. The first volume contains an introduction of about 80 pages, in which Mehring, in concise form, gives the biography of Marx and how developed his philosophy. All separate articles and treaties of Marx are accompanied with introductions and explanatory notes by Mehring, which makes them clear, for present day students of socialism. Without these notes and comments, “Aus Dem Literarischen Nachlass” would remain a sealed book to many of us. It took the broad knowledge of Mehring, who studied philosophy from the same sources and as deeply as Marx himself, to explain the trend of thought of the father of modern socialism.

Takes Active Part in Movement.

Editing the unpublished writings of Marx and Engels did not prevent Mehring from taking an active part in the latter-day development of the Marxian thought of the world. His sharp pen was busily at work against such pseudo-Marxists as Ed Bernstein and Conrad Schmide of Germany and Ernest Unterman of the U.S. It was Mehring who knocked Mr. Unterman on the head when the latter endeavored to prove the superiority of Dietzgen over Marx in the field of philosophy. Mehring pointed out to Mr. Unterman that his knowledge of the subject, about which he wrote and talked so much, was too shallow. Unterman did not discover the contradiction in Dietzgen’s philosophy. Mehring did find it and therefore was able to prove that to comment upon and augment Marx with Dietzgen, is a folly.

Under Mehring’s editorship the Leipziger Volkszeitung became the stronghold of the left wing of the German Socialists. All the polemics against the right wing and the center of the German Social-Democracy found space in that paper. The sharpness of Mehring’s polemical articles made many Socialists view them as personal attacks and not defenses of principles. All such accusations Mehring bitterly denied and the present developments prove so emphatically the correctness of Mehring’s position that there is not the slightest doubt left. He pointed out the danger toward which the German workers were heading; he did it without pity, without mercy, but the workers as a class, did not heed that warning but fell into the hands of their enemies and misleaders.

Mehring’s Attitude During War.

Mehring was the first one to express his indignation when the Socialists went over to the government in support of the war. To see the way that Mehring fought against the betrayers of the proletariat, it suffices to read the “Crisis in the German Social Democracy,” in the preparation of which Mehring collaborated and which has sharp style and clearness and thoroughness in outline of the subject. All through the war Mehring was the bitterest enemy of the Prussian Junkerdom, bourgeoisie and the semi-Socialists of Germany.

Mehring was the first one to voice and glorify the success of the proletarian revolution in Russia. In his letter to the Bolshevik organ, Pravda, he viewed the Russian revolution as the hope of the German working class. Bitterly he condemns the lukewarmness of the Independent Socialists of Germany who view with a smile on their lips the things transpiring in Russia, but do nothing to arouse the revolutionary spirit in Germany. Mehring, very bitterly attacks Kautsky, as a man who knows every word that Marx wrote, but who lacks the revolutionary spirit of Marx. Mehring, truly, had that spirit and courage. Mehring passed away, but his life’s work remains with us and will live forever.

Those who wish to study the outcome of modern socialism can be referred to the inexhaustible sources of Mehring, where they will find the theory and tactics of the labor movement, outlined clearly, convincingly and forcefully. When Liebknecht was se sent to prison Mehring was elected to take his place in the Reichstag; a respectable successor to that younger and fearless fighter of the working class. Mehring and Liebknecht have passed away, but also the old order, against which they fought, in Germany, is dead. They saw the dawning of the new day. They know it will not come easy. The example of the Russian revolution was before Mehring and his broad knowledge of history, convincing him what revolutions are, how they came about and how they are won.

The fruitful life of Mehring is before us like a guiding star. A man, who, to the last minute, did not lose his courage and remained faithful to his life’s work and devotion. Franz Mehring is not among us anymore, but the memory of him and the work of this untiring fighter for working class emancipation, will be among us forever.