A new factional struggle begins its public phase. Immediately after the turmoil of 1927’s faction fight between the Bukharin-Stalin-Rykov majority and the United Opposition was decided with the Opposition’s defeat and expulsion at December, 1927’s 15th Party Congress, a major news crisis developed which would change the course of the Soviet Union, and the world.

The 15th Congress had initiated the first Five Year Plan. While under the New Economic Policy, a multi-faceted debate on implementing industrialization had been going on. Very broadly speaking, two tendencies developed on how to proceed. One, the so-called ‘genetic approach’ based the plan on existing trends within the largely peasant economy (Rykov, Bukharin, Bazarov, Kondratyev, and initially Stalin); another, the so-called ‘teleological approach’ sought to transform the existing economy through rapid industrialization (Kuibyshev, Strumilin Trotsky–expelled at the Congress, and Krzhizhanovsky). As the Congress was under way, multiple issues combined to create severe grain shortages–meaning no food for workers or export for cash.

Stalin abruptly shifted course, proposing grain procurement (which he personally oversaw in January 1928), and then mandatory agricultural collectivization, and rapid industrialization. Many in the old United Opposition, particularly but not exclusively among the Leningrad Opposition (‘Zinovievists’), recanted and were readmitted to the Party seeing their positions vindicated.

Along with the shift internally, came a shift internationally. The February, 1928 Executive Committee meeting of the Comintern first instituted what would become the policies of the ‘Third Period.’ A concept, not the practice, first formulated in the Bukharin-led Comintern whereby the post-World War order would see three periods, the first period being post-1917’s revolutionary wave, the second a period of capitalist stabilization and political reaction, followed by a third period of disequilibrium whereby the ‘united front’ of the stabilization period would be replaced by a policy of ‘class against class.’

This shift which would conflict with many of the Comintern’s constituent Parties’ leaderships, including the U.S. Party’s leadership under Jay Lovestone. In the colonial world where a policy of working with powerful nationalist forces in India, China, and Indonesia had been the policy since 1924’s 5th Comintern Congress, it would also mean a significant change.

In spring of 1928 Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky spoke against the Stalin wing’s plans in Party meetings, particularly the forced grain seizures. The two fights coalesced. As part of the struggle Stalin maneuvered to undermine Bukharin in his Comintern base. This January, 1929 editorial in the Comintern’s official publication does not name Bukharin, then its General Secretary, but is aimed at him as well members of the International, particularly in the German party.

Losing the struggle, Bukharin was removed from his leading positions in the Communist International by the E.C.C.I. of that August, and from the Politburo and as editor of Pravda at the Central Committee’s November, 1929 Plenum. A number of other well-known leaders of the International, like Indian leader M.N. Roy, would be expelled as well. The U.S. Party’s leadership under Jay Lovestone was also expelled, to then constitute themselves the Communist Party (Majority Group) in reference to the Central Committee majority Lovestone held at the time. By far, the most influential of the groups to emerge of the so-called ‘Right Opposition’ was in Germany with such historic leaders as August Thalheimer, Heinrich Brandler, and Paul Frolich.

Many, many more did not fit neatly into any of these categories and would find themselves either expelled or alienated in the International’s factional fights of the latter 1920s.

‘The “Right” in the C.P.S.U. and the Comintern’ from Communist International. Vol. 6 No. 3. January 1, 1929.

THE recently concluded Plenum of the C.C. of the C.P.S.U. summarised results of the struggle which has been taking place in the Party of recent months over the decisions of the Fifteenth Congress. The main line of discussion was on the attempts to retreat from the decisions of the Fifteenth Congress on industrialisation in the U.S.S.R., and the strengthening of the attack on the kulak. The Plenum considered the whole group of problems connected with the practical work of carrying out the decisions of the Fifteenth Congress. The control figures of national economy for 1928/29, i.e., the annual plan of socialist reconstruction, the measures indispensable to a speedier development of backward agriculture, the introduction of the seven-hour day as being at the present stage a fundamental condition of greater attraction of the workers to the work of industrialisation of the country, and finally the enrolment of the workers and the regulation of the growth of the party; (in other words, the improvement of its personnel) so as to ensure successful speedier reconstruction of the entire economy ; a task which now immediately confronts the country and the party,—all this in the aggregate represents the sum of practical measures which must be carried out in order to realise the decisions of the Fifteenth Congress at the present time.

ALL the work of the Plenum was carried on with the idea of resolute resistance to the right deviations and to any reconciliatory attitude towards them. This aspect of the Plenum’s work is of especial importance to the C.P.S.U. It was on this question that the Party impatiently awaited a decision.

In its decisions the Plenum attacks those superficial views which represent right deviation as one easily overcome, as the kind of deviation that could be liquidated by a couple of hundred resolutions and a few dozen applications of so-called “organisational measures.”

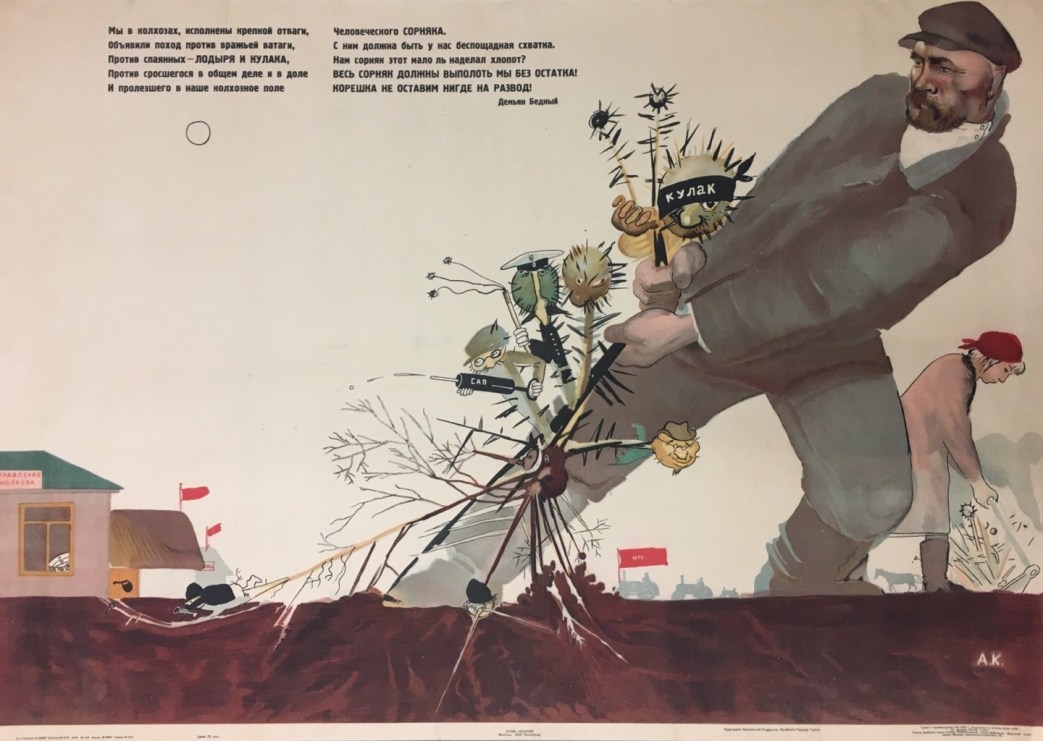

These views are profoundly inaccurate, since the Party has still to carry on a long struggle with the right. The liquidation of the right will be first and foremost predetermined by the socialist reconstruction of the entire economy (including agriculture). So long as there remain millions of privately-owned, peasant commodity-producing farms, elementals of capitalism, so long as the kulaks and Nepmen consequently retain their hopes of a capitalist development of peasant economy, so long as the pressure of the petty bourgeois elements on the Party remains, so long will there be manifestations of right deviations to a more or less degree, and in one or another form, within our Party. Hence the struggle with the right cannot but be protracted.

Trotskyism was an anti-middle peasant deviation. It denied the Leninist idea of the union of proletarian and peasant. Consequently Trotskyism was and remains a ‘‘town’’ deviation. It rests and will continue to rest on the fragments of the old classes (the “suburban” and the bourgeois intelligentsia) and on the declassed elements (students and others declassed in the process of the revolution). Trotskyism, with its idea of the return to war-communism, with its view of the peasantry as a colony of the socialist State to be ruthlessly exploited for the purposes of socialist construction, cannot receive support from among the great masses of the peasantry.

THE right deviation is preponderantly a “village” deviation. It does not reject the Leninist idea of the union of proletariat and peasantry, but objectively it leads to the directing role in that union being conceded to the peasantry, thus retreating from Lenin’s basic condition of the directing role of the proletariat in that union.

Even in 1920, side by side with the “Workers’ Opposition” of that time (Shliapnikov) we had developed a “peasant” opposition also (finding expression in a primitive peasant form in the Red Army). This peasant opposition put forward the proposition that the “peasantry is the elder brother, and the proletariat the younger.” After several years of N.E.P. the peasant idea found its expression in a milder form in the denial of the necessity of industrialising the U.S.S.R. in the immediate future, and in the teaching that it is necessary to agrarianise it during this stage. But in such a form the deviation was far too primitively expressed, and at the present time it is masked behind the teaching that we ought not to set too swift a tempo of industrialisation, that we ought not to restrict the freedom to develop of the kulak farms, since the kulak is still of service to us,—we still need the kulak’s grain,—and that finally we ought not to be in a hurry with our collective farms and Soviet farms. Thus the idea of co-operation of the proletariat with the bourgeoisie for the construction of socialism in the U.S.S.R. is thrust forward: an idea which has nothing whatever in common with Leninism. That is the basic idea of the right deviation in its “Russian” form, an idea which naturally does not make its appearance in such a nakedly cynical form.

THE second peculiarity of the “Russian” form of the right deviation consists in its still not being formulated even ideologically, not to mention any organisational formulation. It is still passing through the elementary phase of its development.

None the less the sources of this deviation are incomparably more profound, as we have seen, than the sources of Trotskyism. It has its roots deeply thrust into the enormous mass of 25,000,000 privately-owned peasant farms (of which only 400,000 approximately were united into collective farms last year). Its tendencies are individualist peasant tendencies, the tendencies of a peasantry not yet drawn into co-operation, of a peasantry still drawn towards capitalism; and consequently they are kulak economic tendencies.

THE concrete forms of manifestation of the right are extremely varied. They appear in various sections of the Party, Soviet and trade union work. Naturally the enormous petty bourgeois masses exert pressure on all phases of Party life. The deviation also appears in the grain collection campaigns, when the lower Party and Soviet workers put obstacles in the way of the sound development of that work on behalf of the interests of the kulaks and the prosperous sections of the middle peasants; it is revealed also in an unjust distribution of the agricultural tax (a lowering of the tax on the kulaks to the injury of the middle peasants), and in an unjust distribution of agricultural machinery (their supply to the kulaks), and in purely social manifestations (Communists fraternising with the kulaks and Nepmen), in the kulak elements’ penetration into the village Party organisations and so on. It is impossible to specify all the varied manifestations of the right in the Party life of the C.P.S.U.

THE right deviation has not yet been crystallised into any system of opinions, but separate elements of that system are scattered everywhere. In consequence of this a ruthless ideological struggle with the deviation, despite the fact that it is still ideologically unformulated, is urgently necessary even now. The Plenum emphasised the absolute necessity of such a struggle in the most resolute fashion, and thus also emphasised the absolute necessity of struggle against any patient or reconciliatory attitude.

IN other Communist Parties there is a different situation from that in the C.P.S.U.

This has to be given particularly definite emphasis, since the purely mechanical application to other parties of the decisions taken by the last Plenum of the C.C. of the C.P.S.U. might result in a complete distortion of the practical tasks confronting those Parties in the struggle against the right.

In the first place it must not be forgotten that in distinction from the C.P.S.U. other C.P.s are still confronted with the task of accomplishing a socialist revolution. And as we know very well from the experience of the Russian party, that task demands the maximum of unity and agreement from those parties. During ten years the Bolsheviks carried out a persistent cleansing of their ranks to ensure this. Without all this preliminary work, which was expressed in a protracted and persistent struggle against all deviations, the C.P.S.U. could not have prepared itself for the accomplishment of the October revolution.

The history of all the other Communist Parties which have developed since the October revolution and emerged from the womb of the social-democratic parties, shows that during these years those parties have also cleansed themselves by way of an internal party struggle more and more from the social-democratic human ballast (Levy, Frossard, Bubnik and company) which they had brought out with them. Now these parties are more homogeneous than they were ten years ago. But the process is far from being completed.

BUT meantime the intensification of the class contradictions and the class struggle and the swift approach of the war danger demand of these parties a swifter cleansing from social-democratic elements.

The sources of the deviations in the C.P.S.U are also different. While in the C.P.S.U. the right deviation is still passing through only its elementary phase, in other Communist Parties the deviation has already been formulated not only ideologically but in places organisationally also. This essential difference must not be forgotten, for it shows that the purely mechanical application of the decisions of the last Plenum of the C.P.S.U. to other parties may lead to a number of serious errors.

But the common feature of the “Russian” and the International right deviation is the tendency towards co-operation with the bourgeoisie (in the capitalist countries in the form of co-operation with the reformists). This tendency arises out of the fear of struggle in circumstances of an intensification of the contradictions existent both in the U.S.S.R. and in the capitalist countries. Naturally this tendency takes on different forms in the U.S.S.R. and in the other countries, since in the U.S.S.R. the construction of socialism is already proceeding, while the other countries are still only confronted with the social revolution. But despite this enormous difference it is this basic tendency towards co-operation with the bourgeoisie which unites the right on the international scale. And this also must in no circumstances be forgotten.

THE task of cleaning out the right elements assumes a particular importance in regard to the directing party organ. The approaching gigantic class and war conflicts demand the transformation of these directing organs into revolutionary staffs, not in any figurative, but in the actual meaning of the words. And in the staff there must be no doubters, no waverers, no unstable elements ready to retreat at the first failure; in a staff there must be no panic-mongers.

We do not in the least intend to imply that there must be no ideological struggle. That would be absolutely unsound. The ideological struggle is indeed needed. We only desire to emphasise the profound difference which exists on the question of attitude to the right danger between the U.S.S.R. and other C.P.’s. The basic task of the C.P.S.U. at the present stage is the waging of a ruthless ideological struggle against the right and so-called “organisational measures” can play only a secondary role. But in other C.P.’s the basic task is a cleansing of the right elements, which will not in the least eliminate, but will on the contrary, demand of the party an intensified ideological struggle against the right deviation.

A number of incidents which have occurred in the C.P.’s of recent times have provided extremely clear confirmation of this. As an example we need only to consider what has been happening and is still happening inside the German C.P. The right-wing attempts in connection with the Wittdorf affair to overthrow the existing Party leadership and to capture the power for themselves, their organisation inside the Party of fractions which publish their own fractional newspapers and refuse to subject themselves to the decisions of the C.C., which violently attack the decisions of the Fourth R.I.L.U. Congress and the Sixth Comintern Congress, which sabotage the struggle in the Ruhr, and are openly preparing a schism within the Party, provide a pattern of what awaits our Party in the event of revolutionary or war complications (which are incomparably more difficult than the complications caused in the Party by the Wittdorf affair) if the rights retain the organisational possibility of sabotaging the revolutionary work of the C.P.’s and exploit internal Party difficulties to this end.

AT the moment we are not discussing the question of the forms of reaction to the activities of the rights in the German and other C.P.’s. This is another subject: that of the methods necessary to cleanse the C.P.’s of the rights. The question which interests us at the moment is the estimate of the present experience of the struggle with the rights is that without a resolute cleansing of mate of experience in the light of the general revolutionary tasks confronting the C.P.’s, and also in the light of the immediate revolutionary tasks.

The chief conclusion to be drawn from this survey of the experience of struggle with the rights is that without a resolve cleansing of the C.P.’s of the capitalist countries, and in particular of the leading Party organs, from the rights, our Parties will not be able completely to fulfil their revolutionary obligations.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-6/v06-n03-jan-01-1929-CI-grn-riaz.pdf