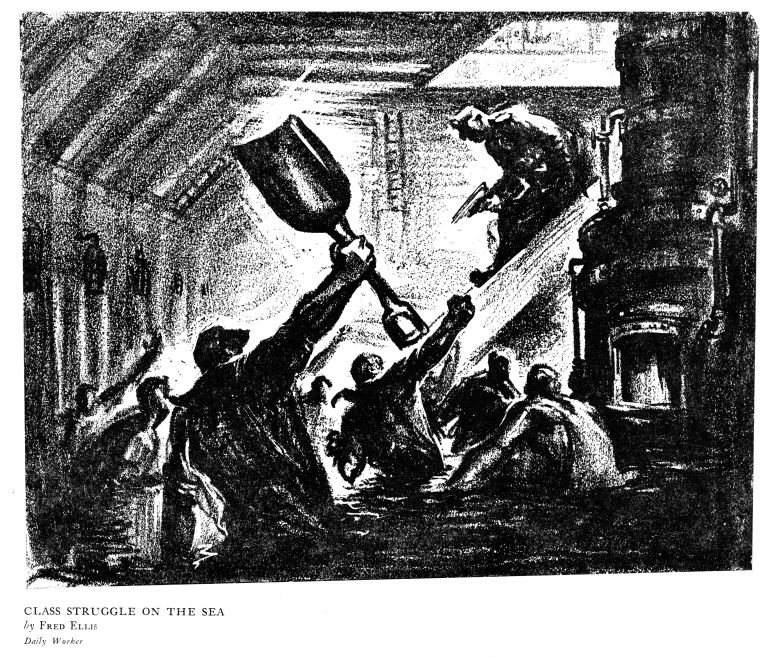

Meet Fed Ellis, the worker-artist responsible for so many of the remarkable images to appear in the Daily Worker in the 1920s and 30s.

‘Fred Ellis, Artist of the Proletariat’ by A.B. Magil from The Daily Worker. Vol. 5 No. 315. January 5, 1929.

IN the early part of the year 1905 twenty thousand Chicago stockyard workers went out on strike. It was a strike against one of the most brutal, most diabolical slavery systems ever devised by American capitalism. Talk about slavery. Twenty thousand workers, most of them foreign-born, were working under conditions that make your hair stand on end–12, 14, 16 hours a day for wages as low as eight or nine dollars a week, working in bitter cold and oppressive heat, in overwhelming stench, in damp, germ-laden chambers, with rheumatism and all sorts of fiendish pains stabbing them all the time.

Twenty thousand of them rose in revolt. One of the strikers was a 20-year-old youth named Fred Ellis. He had gone to work in the yards two years before and had gotten a job as trucker. The truckers transported cases of prepared meats from the refrigerators to the cars to be shipped to various parts of the country. They had to keep constantly on the run between the refrigerators and the cars. The temperature in the refrigerators was 5 below zero. Outside in the bitter Chicago winter it was little better. No coat, half-frozen, the wind lashing your face and–speed, speed!

In the summer it meant stepping from 5 below zero into an oppressive ninety-odd, hundreds of times a day. If an exhausted worker slowed up for a moment, whack would go the stick of the straw-boss. The worker would stagger painfully into the trot, the human machine would go thru the motions again.

The average work day was 12 hours; pay 162 cents an hour, $1.98 a day. Of course they made more in fact, during the busy season they could clean up quite a pile on Saturday working 18 hours–whether they wanted to or not. Get to work 4 in the morning. Fifteen minutes for breakfast, 30 minutes for lunch, 15 for supper–and 18 solid hours of back breaking work.

The truckers didn’t kid themselves. Each man worked on, knowing he couldn’t last, no matter how strong he was to start with. Everybody knew that the average work-life of a trucker was four years. After that he was thrown on the garbage heap. Used up. Next!

The Swifts and Armours never threw any parts of their slaughtered animals away, no matter how foul and moldy. But a man who had sold his life to them for a few years was thrown away as so much garbage. And there was always a finer strong, healthy fellow to step into his place.

TWENTY thousand of them in revolt in Chicago, in the year 1905. Thru the hot, weary months, thru seven long bitter months they fought on. Scabs were brought in, paid high wages, fed, clothed, lodged, gorged with whiskey. The police and the courts hearkened to their masters’ voice. Mr. Swift might be traveling in Europe, enjoying the masters in the Louvre or the pure, golden air of Florence where so many great men had walked. But he would break the back of the strike. And meanwhile the huge, tireless stockyards worked on as usual, feeding their rotten, diseased meat, flesh and blood, of animals, of human beings, to the country.

The strikers were driven back. Many of the scabs were retained and so nearly everybody was put on part time; you could starve twice, as fast now. The truckers had struck for a raise of from 16% to 17% cents an hour. A month after they returned they were cut to 15% cents, Five below in the refrigerators, 18-hours on Saturdays, speed, speed! A man lasted four years and was thru…

Mr. Swift bought another old master. The air of Florence ah, one can feel the spirit of Dante himself alive in these streets.

“I USED to see the sun only on, Sundays,” Fred Ellis said to me. It was 23 years after, in the office of the Daily Worker in New York City, and Fred Ellis, staff cartoonist of the “Daily,” was being interviewed.” Put “interview” in quotes. Fred Ellis is too simple, unpretentious a person to be interviewed. He just talked while getting ready to start another drawing. It was unusual for Ellis to be talking about himself. He never does. Now he was talking about himself because he was asked to.

I gasped at what he told me of the life in the yards. “How could you stand it?” I asked.

“I don’t know, I just did. You can stand anything if you have to.” His eyes were sad.

“It was a miserable life. Like being in jail, only you worked much harder. Two or three times a week we’d go to sleep with our clothes on, too tired to take them off. Sometimes men would get desperate, they’d let fly a hook and a straw boss would be on the ground with the blood spurting out of him. Men become killers in such a life.”

Upton Sinclair has told the story in his great epic of the American class struggle, “The Jungle”–perhaps the only really revolutionary piece of writing Sinclair has done. Sinclair was charged with hysterical exaggeration and falsification of facts.

“What do you think of “The Jungle,’ Fred? Did Sinclair tell it all straight?”

“He didn’t tell enough. There were many horrible details that Sinclair never learned.”

Working 12 hours a day and more left you little time for leisure pursuits. By eating cheaply and sparingly, buying almost no clothes, spending practically nothing on amusements, Ellis in the course of three years managed to save even out of his miserable wages $100. He had always liked to fool around with pencil and paper, drawing sketches of things and people. So he decided to stop work and go to art school. He went to the Art Academy in Chicago for two months and then had to quit because his money was used up. That ended his formal art education.

But Ellis was through with the stockyards. He became a sign-painter, painting large outdoor signs. For 21 years he worked at this trade, being active in his union all the time. He was just one of the hundreds of thousands of rank and filers, unknown except to his immediate circle, working in Chicago when he could find work there, traveling to other cities when he couldn’t, always hunting the elusive job. He had no contacts with the organized movements of the workers outside of the American Federation of Labor

Later on Ellis was elected an officer of his union and became a delegate to the Chicago Federation of Labor. In 1919 the Chicago. Federation, then under progressive leadership, launched a weekly magazine. The New Majority. There were drawings by Art Young and Boardman Robinson in The New Majority, reprinted from the old Masses, with which he was familiar. The thought occurred to him that he might be able to do some suitable drawings, and so he tried. They were accepted and printed. They marked the first emergence of Fred Ellis as a working class artist.

Ellis contributed more drawings and continued to draw for The New Majority while working at his trade.

In 1919, while working on a scaffold on the fifth floor of a building in Chicago, Ellis suddenly slipped, lost his balance, whirled thru dizzy air and landed in a heap on the hard asphalt pavement. Some people die from a fall like that. Ellis was lucky. He lived. He spent six weeks in the hospital and for two years walked with crutches or a cane, unable to work. Ellis was lucky.

William Z. Foster was circulation manager of The New Majority and it was through him that Ellis formed his first real contacts with the revolutionary movement. While in the hospital he was visited by John Reed, Art Young and Ralph Chaplin. Later Robert Minor came to see him at his home. Minor had just returned from the Soviet Union and he took Ellis over with him to see Bill Haywood. It was Minor, himself a famous working-class artist, who took Ellis under his wing and helped develop his great talents.

“Bob Minor taught me nearly all I know about cartooning,” Ellis said. When towards the end of 1923 the Workers Party decided to launch a daily organ, Ellis did drawings for the campaign for funds and subsequently became a frequent contributor to the Daily Worker and the Liberator. He continued to work at his trade, though he found it increasingly difficult because of his injuries and the psychological effect of his accident had had on him.

“I quit three jobs in a single month,” he said, “because I couldn’t go up high. I lost my nerve after that five-story fall.”

In the summer of 1927 Ellis came to New York to become staff cartoonist of the Daily Worker.

“How do you like working on a revolutionary paper?”

“It’s the berries!”

“Wouldn’t you like to work for the World or some other capitalist paper and draw a nice fat check and have lots of fame?”. I ask half-jokingly.

“No, I wouldn’t.” Then after a pause: McCutcheon of the Chicago Tribune (he’s a $25,000 a year man) once told a friend of mine that he admires me as an artist, but thinks I’m a damn fool. But then he’s a $25,000 a year man and I suppose that gives him the right to consider me a damn fool.”

I asked Ellis what his method of work was.

“That’s what I’ve been trying to discover for years,” he said. “If I could find out, it would make things much easier, I suppose it’s my lack of academic training. Most cartoonists work according to a definite scheme.”

Ellis had to start work on another drawing and so the “interview” was over. Most newspaper cartoonists do one drawing a day and call it a day’s work. Ellis sometimes does two, three and more. Nothing that is related to his field is beneath him. Ellis is no prima donna. And he has a fatal weakness: he can’t say “No.” Labor Unity may need a drawing for the next issue, the Labor Defender may want some pictures retouched, a working-class organization may want a poster for an affair it is running or he may be asked to do a few sketches for a shop paper. It’s all in the day’s work for Ellis.

The story of the rise of Fred Ellis from stockyards worker and sign-painter to revolutionary artist will not be found in any of the success magazines. Lofty literateurs do not write profound articles on him for the Dial. His name is unknown in the art-haunts of Paris. Plainly, Fred Ellis has no “standing.” It is not really the story of a “rise” at all. Merely a change of jobs. Fred Ellis was a worker 25 years ago; he is a worker today. The difference is that now he is a more conscious fighter for his class, fighting where he can be of the greatest good.

Suffice it, that Ellis does have “standing,” but with a different class. His drawings have been reprinted in the Communist press of the world and hundreds of thousands of workers have been influenced by them. And that is the only sort of “standing” that means anything to Fred Ellis.

Class consciousness with Ellis is not something that has grown out of intellectual conviction. It is not even primarily an emotional thing. It is a normal function of his being, like eating and sleeping. One can no more pry him loose from his class than one can pry him loose from his heart and lungs without destroying him. And that is why Ellis is such a thoroughly unconventional artist personality. He is an artist who rarely talks about art, who thoroughly dislikes all esthetic pose as he dislikes cant and sham of every kind.

Fred Ellis is a worker. Fred Ellis is one of the greatest working class artists in the world.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v05-n315-NY-jan-05-1929-DW-LOC.pdf