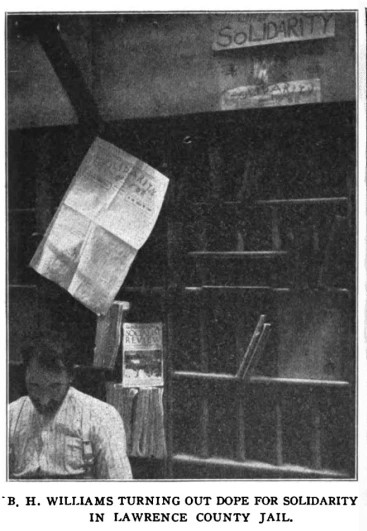

Veteran organizer and editor of Solidarity, Ben Williams reports on the work of the 6th I.W.W. convention in September, 1911 with the main debates over centralization vs. decentralization.

‘The Sixth I.W.W. Convention’ by B.H. Williams from International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 5. November, 1911.

NOT long since, a very pertinent question was asked by Frank Bohn through the columns of the Review. That question, Is the I.W.W. to grow?” has gained an affirmative force in the minds of many of us who attended the sessions or reviewed the proceedings of the Sixth Annual Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World, which adjourned its ten days’ sittings in Chicago on September 28.

A number of disquieting rumors were afloat prior to the convention. One was to the effect that the “antis” as they are familiarly called would be there in full force and with the avowed purpose of so amending the Preamble or changing the Constitution, as to make the I.W.W. once and for all an “anti-political” organization. Another had it that the supposed “antagonism between the rank and file and the general administration” would result in a split at the convention, and thus again interrupt the constructive work of the organization. Other rumors went the rounds, all tending to the conclusion in the minds of those who circulated them, that “something was going to happen at this convention,” to show that the I.W.W. did not understand itself or the problem it was aiming to solve.

None of these predictions were verified. The question of “politics,” a burning question up to and including the stormy Fourth convention (1908), was not discussed at all by the Sixth convention. Some local had proposed the following amendment to the I.W.W. Preamble: “Realizing the futility of parliamentary action, and recognizing the absolute necessity of the industrial union, we unite under the following constitution.” Although it is safe to state that a large majority of the delegates were non-parliamentarians, the above proposition was voted down without discussion.

The question of the “general administration and the rank and file’ was not so readily disposed of. Many proposed constitutional changes were brought before the convention, chiefly emanating from local unions in the Rocky Mountain and Pacific states, all with a view to modifying or minimizing the power and privileges of the General Executive Board and the General Officers. Debate on these proposals lasted for several days. The relations of the different parts of the organization to each other were thoroughly threshed out. Misunderstandings were cleared up. All of the proposed amendments were voted down. Several delegates who came instructed by their local unions to vote for them, admitted that after due consideration and more enlightenment on the questions, they were opposed to their instructions, but none of these voted contrary to the wishes of their constituents.

As above stated, nearly all proposed changes in “behalf of the rank and file” came from western locals. In order that this may be clear to readers of the REVIEW, it may be well to point out here some of the sectional differences between the East and West.

That portion of the West between the Rockies and the Pacific is still an undeveloped country, vast in area and very thin in population. The principal industries are agriculture, lumbering and mining. All three, though more or less trustified, are undeveloped. Jobs are far apart. Workers, classed as unskilled, are compelled to shift constantly from one section to another and from one industry to another. As a consequence, “mixed” or recruiting locals become a necessary feature of I.W.W. organization in the West; while INDUSTRIAL unions proper are difficult to form and still more difficult to maintain on account of their shifting constituencies. Moreover, the rough and ready life of the migratory worker tends to self-reliance and individualisms, which are far more pronounced in the West than in the East. Every member becomes an agitator, and many “soap-boxers” have been developed to carry the message of industrial freedom into every nook and corner of that section.

Strange as it may seem at first thought, this tendency to individualism has given rise to an undervaluation of individual initiative in the administrative affairs of the organization. It is apparently a case of being unable to see the forest for the trees. Since there are so many capable individuals in the West for secretaries, organizers, editors, etc., it follows logically in the minds of some that the I.W.W. everywhere should have a complete change of officers at least once a year in order that no individual may be tempted to usurp too much power. Again, the necessary “mixed” local form of union—on loose geographical lines—has stamped its character on the minds of our western members, and caused some of them to question the industrial form of organization with its proposed centralized administration.

Thus we see in the West, individualism in practice, combined with a theory of collective action that scoffs at individual or group initiative by general officers and executive boards, and conceives the possibility of “direct action” in all things through the “rank and file.” Hence the proposal from several western locals to abolish conventions and inaugurate a system of legislating exclusively through the initiative and referendum. Hence also the proposals for rotation in office and for minimizing the power of the general administration.

On the other hand the eastern delegates bring to the convention different ideas acquired from a different environment. The East is a great beehive of industry highly developed and centralized. The worker in a steel mill in Pittsburg, for example, knows that his employer is a gigantic corporation, which also employs miners in Minnesota. He does not, however, think of Minnesota or of Pennsylvania in a geographical sense. He thinks only of the steel trust. Locality is of little significance to him, though he may be anchored in one spot for life; the industry is everything. And since that industry is a trust, with centralized administration, the eastern worker naturally demands a similar organization among the wage slaves. He sees no chance for quick and effective action through the unwieldy method of legislating by referendum. Without the individualistic spirit himself, the eastern worker nevertheless recognizes the value of individual initiative in promoting mass action and in executing the mandates and requirements of the organization.

The problem before the Sixth convention was to preserve the balance between these two sets of ideas. In that, the convention succeeded admirably. While recognizing the need of local initiative and freedom of action, at the same time the convention insisted upon the equal necessity of preserving the integral organization, through a proper understanding and adjustment of the relations of one part to another—of the individual to the local, of the local to the general administration; and vice versa. The sum total of its conclusions along this line was that few constitutional changes are now necessary; that the I.W.W. is on a working basis and should direct all its energies toward organizing the One Big Union of the Working Class in the industries of the nation. On that basis the East and the West came to a common understanding. Moreover, for the first time in an I.W.W. convention, they found fraternal delegates from the South, who were in enthusiastic accord with the same purpose. These were the representatives of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers, who in only a few short months of experience in unionism have developed splendid fighting qualities in their combat with the lumber trust in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas.

Little need be said of the personnel of the delegates to this convention. There were few striking contrasts among the men. Although here were fellow workers who had been active in the struggles of the old Knights of Labor, the Western Federation of Miners and other militant unions, and had gained much practical experience by the way, still in the eyes of the world at large they are “unknown men.” “Intellectuals” were conspicuous by their absence. Most of the delegates were young men full of the fire and enthusiasm of youth; somewhat crude as to their knowledge of parliamentary usage, but very much in earnest in debating the welfare of the organization. They were I.W.W. men first, last and all the time, with a singleness of purpose that augurs well for the future of the economic movement.

Without presenting any marked contrasts or any striking incidents, the Sixth convention nevertheless has marked a distinct epoch in the development of the I.W.W. It has shown that the stormy periods and internal struggles of past years have not destroyed the vital principle of the organization; and that from now on the I.W.W. should move forward with increasing numbers and power.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n05-nov-1911-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf