A detailed history of the mass textile strikes in France’s Roubaix-Tourcoing region during 1921 from Joseph Tommasi. Tommasi was a leading French syndicalist, an officer in the C.G.T., he became a founder of the French Communist Party in 1920 and a member of its leading body.

‘The History of a Labour Battle’ by Joseph Tommasi from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 1 No. 13. December 2, 1921.

After seventy-six days of battle, which at times was very violent, the workers of the Roubaix-Tourcoing Region, belonging to the textile industry so harshly exploited by the heartless employers, have just gone back to work without having been able to terminate successfully the task which they had undertaken.

Causes of the Movement.

In a preceding article I explained the origin of this movement which had for its sole aim the prevention of a new reduction of wages at present insufficient for the excessively high cost of living in this region of the North, which for two years has been a prey to the most rapacious kind of speculation attracted thither by the alluring business opportunities offered by the reconstruction of the devastated regions. That movement was not spontaneous, however. For months the masses had been stirred up by a revolutionary minority which in spite of many difficulties strove to bring them to a better comprehension of the class-struggle.

Since the armistice, and indeed up to the last few months, the Social-Democrats of Roubaix-Tourcoing were content with a policy of class-collaboration, which, however, had not brought much good to the workers. Several months ago, while at Roubaix there still existed a certain amount of confidence in these men and their reformist methods, at Tourcoing, and more especially at Halluin, the workers rid themselves of such methods whose value they knew.

These methods had run their course in the year 1920, when the proletariat of the textile industry of the North had to “accept” a reduction of 30 centimes per hour, without being able even to put up the least resistance.

The employers knew this new spirit, but did not credit it with the value which it really possessed, and they underestimated the extent of its penetration among the masses.

It was thus that at the beginning of August the employers decided to engage in battle for two purposes. The first was to force a new reduction of 20 centimes an hour; and the second was to assassinate the labor-unions which would be too dangerous a weapon in the hands of the workers on the day when the revolutionary spirit penetrated these labor-bodies.

On the employer’s side–There were 300 big manufacturers of the Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing region, combined into a “Consortium,” with two large fortunes at its head which the war and the German occupation had not in any way diminished, on the contrary, it had grown. As secretary there was a rogue by the name of Ley, a workingman’s son, himself a workingman who had been somewhat of an anarchist before the war, and had risen in the world by selling himself and betraying his former comrades.

This unscrupulous individual had been a lackey to the “Kommandantur” during the occupation, an auxiliary to German militarism against the unfortunate workers of the region. Moreover, he had got hold of so much documentary information concerning the greater number of the employers composing the “Consortium” that no one dared to budge or protest while this vicious individual was manoeuvring in the most ignominious fashion, and by his sole misdeed, reducing tens and tens of thousands of workers to the greatest misery.

During these three months he was to be the accursed soul of this criminal action, and in order to constrain the workers to beg for mercy he was to succeed in bending the government, the magistracy, the police and the army to his purpose. He was io employ all means, including the worst, in order to triumph.

On the workers’ side—In spite of the decisions, always favorable to the workers, which were given by more or less official bodies before which the questions was put, the employers nevertheless persisted in wanting to reduce wages. Uncovering their batteries at last they spoke of unemployment, took up the theme so dear to the hearts of the Labor Confederate pontiffs—that of the “general interest,” of “economic renaissance,” asserting moreover that this reduction was necessary for the revival of business in the Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing region.

Before such an assertion the workers’ conscience awoke. At first there was stupor, then anger, then a cool determination to enter into battle, since that seemed to be the employers’ wish.

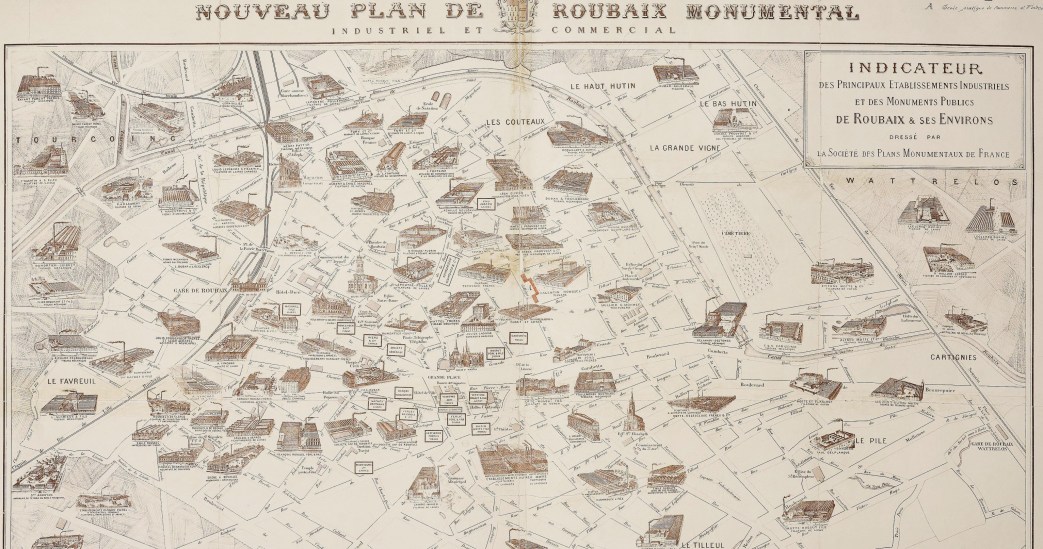

At the beginning of August the strikers multiplied in number. In Lille the cotton-workers quit work, followed a few days later by the weavers. In Roubaix the construction-workers left their work yards. Wattrelos, Wasquekal, Halluin, Bousbecque, and Verviers follow. In all the centers there was a vast quivering which shook the working-class. The provocations by the employers, the discussions, the tendencies which had taken on a formidable acuteness since the secession at Tours and at the Congress of the C.G.T. held in Lille in July all this awakened in everyone the need for knowledge and resistance.

It is under such circumstances that the general strike of the textile industry broke out on August 16. The employers persisted in wanting to ‘reduce the wages by 20 centimes an hour at two turns, whatever may be the cost of living.

More than 60,000 workers entered the battle at once. The proletariat had suffered too long a time. It was at its rope’s end, determined to undergo the last sacrifices in order to impose its rights upon those who live in wealth from its labor and its misery. The discipline impo6td upon it seemed an unbearable chain, it felt the need of throwing itself into “direct action”. Its militants would lead it wherever they wished.

The first week, however, was calm. Processions of 20,000, 10,000 and 40,000 strikers marched through the streets of Roubaix singing the “International,” “Revolution,” the “Carmagnole”, songs which left no doubt as to the frame of mind of this admirable crowd.

The second week things were somewhat spoiled. The “Consortium” tried to disrupt the movement with the aid of more or less clean manoeuvres. The response was not long in coming. Yellows (they were not numerous) were prevented from working; trucks were overturned, windows were broken. Electricity was in the air, not much of it was needed in order for the storm to break.

At the “Consortium” they did not make a misstep. They waited for better days.

The Central Strike Committee, confining itself to the methods accepted by most of the militants which compose it called for calm, placing their confidence in the simple force of right to triumph in this combat.

During the third week nothing happened which would give any hope for an arrangement benefiting the workers. As for amiable arrangements, no one wanted that. The C.G.T. was expected to give the order lor making the movement general, as that was the only thing which could force the employers to give up their insolent arrogance and their abominable pretensions.

This decision was taken on September 12; already one month had passed since the beginning of the struggle between employers and textile workers. All the labor-bodies, such as those of metallurgy, construction, gas, electricity, food, municipal service, newspaper dealers, printers and lithographers had all entered the battle to support the cause of the textile workers for which the construction workers of Tourcoing, Roncq and Halluin, and the transportation workers of Roubaix-Tourcoing had already been fighting.

The power of the electric current was cut in half. The lighting of the cities was reduced by three-quarters. For twenty-four hours the food-supply workers and the undertakers’ assistants ceased work and resumed it again only on the authorization of the Strike Committee. The cates were closed, the bartenders’ union solidarizing with the workers. The sale of papers was prevented. The local sheets such as the “Journal de Roubaix” and the “Egalite” no longer appeared. A labor union customs-line was established on the frontier. Thus, the Belgian workers could not leave their territory. A red police functioned and spread over the city.

Two faint shadows appeared in the picture. The municipal employers of Tourcoing had not followed. Their union had resigned from the Labor Exchange of Tourcoing eight days ago because this Exchange had dared to name a delegate of its tendency to the administrative commission of the Departmental Union of the North after the Congress of the Departmental Union and of the C.G.T. The majority of the Labor Exchange of Tourcoing declared themselves with the Revolutionary Minority, as at the Departmental Congress, and naturally a Minority delegate replaced the preceding one who had been of the Majority. On account of this the municipal workers quitted the Exchange and did not go on strike.

The second shadow was that of the street-car employees of Roubaix-Tourcoing. With them the ill-feeling persisted. However, it had more justification lor at the end of the nationalization strike the street-car workers had suffered a great deal. The union had to struggle more than five weeks after the strike to prevent reprisals. During that time the Civic League and the conductors provided a limited service. No one took up the defense of the street-car workers. No organization took a stand against the Civic League. That was a great mistake on our part. The street-car workers of Roubaix-Tourcoing had not pardoned us for that. However, the union workers of the street-cars were not stubborn in face of the big demonstrations, and they led the cars back to their barns. Only the “Mongy” ran from Lille to Roubaix or to Tourcoing, taking care to stop prudently before the toll-stations of these cities.

There were incidents: trucks overturned, automobiles destroyed, windows broken, street-cars damaged. The troops were called. The Sixth of the Light Cavalry and 509th of the Tanks (Champions of the Tanks of France) were going to keep up the bloody tradition. It was of little avail. The strikers were resolute.

The 75,000 working-men and working-women, animated by the faith of revolutionists, did not bend before the governmental threats.

Who then was able to cause such a perfect unity of action? It was the employers’ answer, read at the prefecture by M. Boulin, divisional labor-inspector which accomplished this.

General Strike.

Thus the decision was taken—with some rare exceptions all the organizations entered the bade in order that the employers should not succeed in their dishonest designs.

But the moment it broke out, it appeared that the general strike of all the labor-bodies would find itself weakened through the very will of those who caused it to break out. Too many contrary influences brought it about that the general strike did not achieve what one had a right to expect from it, and less than fifteen days after it had broken out, the general strike came to an end without the big filibustered of the “Consortium” being forced to reduce their pretensions even by the smallest amount.

From that moment on, it was easy to foretell what would be the end, unless the Central Strike Committee would decide to take into consideration the suggestion of our communist comrades of Tourcoing and give up the methods made use of for more than a month and a half, which ended with nothing, except compromises which the workers refused to listen to.

The employers’ offensive.

With the general strike ended, the employers thought that the textile workers were going to make honorable amend, and to start the factories working again with this new reduction of salaries.

But there again they were very much mistaken, for the duel continued—determined, ferocious, decisive. Although the workers suffered the direst misery, they were determined io struggle to victory in their just cause.

But though the strike was holding out, the leaders did not think there was any necessity for changing the forms of action applied from the very beginning of the strike.

The attempt was still being made to bring about a conference before an arbitrator and they were certain of easily proving to this arbitrator the justice of the workers’ cause.

About October 15, while the battle continued on the side of the workers with very legal tactics, a formidable offensive started from the side of the “Consortium” against all the militants and even the strikers Before everything else the employers’ side made sure of the aid of the government and the police.

The prefect Nodin, as a good watch-dog for Capital, did everything within his power to break up the movement. Whereas, during an interview, the president of the Cabinet, M. Briand himself, congratulated the militants on their good behavior in the strike, an order was given to flood the region with a host of military and police.

At the same time there was an avalanche of private letters addressed to workers—these letters written in such tricky, Jesuitical terms that inevitably a certain uneasiness was bound to grow up within the ranks of the strikers.

Next there was an avalanche of posters, all of them just as ignoble and insulting to the private life of the militants, which was calculated to enlargen the breach made in the ranks of the workers by the first manoeuvre.

Finally, for a whole week, the officers, the policemen, the prefect-officials raided the homes of the workers, in order to hasten the disruption within the ranks of the workers. And then, supreme manoeuvre, one fine morning the sirens began to blow, and the doors to open under the protection of the armed forces of the state.

A movement for resumption of work became immediately apparent. The centers subjugated by the methods and the men of reformism surrendered in part.

At Lannoy this movement of resumption of labor began, and immediately spread to Croix and Roubaix and also to Wattrelos like wildfire, stopping only at the gates of Tourcoing.

At Tourcoing thanks to the confidence inspired by the men of action and by the active methods applied by them, the evil did not penetrate; and up to the last day, when it was deliberately decided to go back to work this was a compact block which was to remain in the battle.

Al Roncq and at Malluin which were more decidedly won over to Communism and to its methods of direct action, the struggle ended to the advantage of the workers with a renewal of the force of the working-class to organize for battle.

And during all this time the “Consortium” directed its most decisive blows on the points which appeared to it most vulnerable.

Without embarrassing itself by formulas which seemed to be the foremost preoccupation of the Central Strike Committee, the Consortium directed the battle clearly on political grounds.

In addition to the posters insulting the private life of al! militants, other posters were full of the writings of trade unionists more inclined towards reform and dissidence–writing cither against the “Russian Revolution”, and the “proletarian government” or against the Communist Party.

On Wednesday October 19 it was noticed that a number of workers resumed labor in a majority of the factories. On the next day the number increased tenfold. Friday, the 2nd was an inauspicious day for the strike, and according to the expression of a militant of Roubaix, the laborers crowded to resume work to such an extent that “I was ashamed of it.” By Saturday, the 22nd, the resumption of work was complete and on Monday the 24th, the workers’ demonstration which came from Tourcoing towards Roubaix was apprised of the fact that most of the factories were in operation.

In view of such a state of things the Strike Committee of Tourcoing, after having fully weighed the consequences of its move, decided on the 30th for the resumption of work for Wednesday November 2nd, and demanded the Central Strike Committee to make a decision immediately.

The leading reformists of Roubaix did not come to this meeting of the Central Committee for reasons more or less obvious.

It is impossible to take up one by one the events of these last eight days of the strike, but what we ought to do without any sort of reserve whatsoever is to draw the lessons from this labor battle, and they are many.

About the C.G.T., also, there is not much to say. It had the opportunity to get back again into the good graces of the workers. Buried in its policy of self-denial, it was incapable even of fulfilling its promises.

The fighters of Roubaix, seeing nothing but promises, seeing that the roads to conciliation were definitely closed, that the war of usury had not reduced in any way the employers’ forces, fell back. Already suspicious, they became definitely disaffected, and thus the movement lamentably gave way in spite of the valor of the fighters.

The last fifteen days, out of the 4000 strikers remaining in the struggle, five to six hundred and rarely as much as 800 participated in the demonstrations held in Roubaix, while at Tourcoing and Halluin all the workers look part in the demonstrations.

Conclusions.

The conclusions which we can make are the following Never, in spite of everything that might have been said, was the movement essentially economic. It immediately took on the aspect of a social movement, and all the forces of reaction hastened to join hands in order to defeat the workers.

Wherever the Reformists and Socialist Dissidents (for there is no difference between the two) tried to apply their policy of “cooperation” of the employers and the workers, there was defeat and disbandment.

Wherever the Communist spirit directed the action, there was success, or the conservation of the force of the union-organization. For example: Roubaix—a loss of 50 % for the textile union.

Tourcoing–There were 8,000 organized workers before the strike, and the week following the resumption of work, the number of union-workers was 12,000.

Halluin–is Communist, and Warn de Wattine, Secretary of the Union is at the same time aid to the Communist mayor of Halluin. At Halluin the workers resumed labor after having obtained satisfaction and with all the workers, numbering 4000, joining the unions.

The anti-political policy of the labor-unions, the ignorance of political economy, has just been struck a decisive and mortal blow in the course of the strikes in the North.

The Dissidents among the syndicalists and the political elements have realized it very well. No manoeuvre was overlooked by them, in spite of all deceitful and pleasant appearances.

Not having succeed previously in driving out the militants of the C.S.R. (Comites Syndicalistes Revolutionnaires) and the communists, the politicans and the immovable officials of the syndicalism of the “Union Sacre” attempt now to exclude the militants and the unions who saved the honor of the workers in this battle, instead of working for the regroupment of forces within the union organization.

After having thrown out the Minority militants and the communists from the Co-operative of “Peace” at Roubaix they would like to get rid of them by throwing them out of the “Confederation Generate du Travail” under the rather odd pretext of “indiscipline.”

They will not succeed, and Roubaix, Tourcoing, and Halluin will become so many fortresses of Communist-Syndicalism, joining the already numerous forces (which to-morrow will be the majority) which, fully conscious of the necessities imposed by the class-struggle, are preparing to join the revolutionary organization of workers—The International of Red Trade Unions of Moscow.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1921/v01n13-dec-02-1921-inprecor.pdf