More interesting deliberations on the questions nation and its place in the class struggle raised by the first global war from Communism’s U.S. founder Louis C. Fraina.

‘The Class and the Nation’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol. 4 No. 2. January 15, 1915.

THE Russian Socialist, Paul Axelrod, insists that a thorough historical study of the nation is indispensable for Socialist reconstruction after the war. This is an acceptance of the fact that our attitude to the nation is the decisive factor in the reorganization of the Socialist movement; and our attitude to the nation carries with it the reconstruction of our national and international policy and tactics, not simply in relation to war, but to the whole scope of the movement.

A mere historical study, however, is in itself insufficient; few Socialists would disagree, historically, about the significance of the nation as a creation of the bourgeoisie. The important point is a contemporary study of the nation and its role in social development, and the whole subject of the nation and parliamentary government within the nation. Parliamentary government is part and parcel of the nation, fundamentally one problem and one manifestation, and should be considered as such.

But even historically Socialists are not all in harmony in their conception of the nation. There is an assumption among some Socialists that, while the nation is the particular creation and form of expression of the bourgeoisie, the nation is just as important as the class and that the struggles of nations each with the other function as dynamically as class struggles. History refutes this assumption- national struggles are a form of manifestation of the class struggle.

The historical generalizations concerning this problem may be summarized as follows:

1. The nation is the expression of a particular social and economic system and the class representing that system.

2. The destiny of a nation is determined by the development of the economics of its social system and its ruling class.

3. Competing nations represent competing social-economic systems and ruling class interests.

4.The hegemony of a nation at any particular epoch represents the hegemony of the most highly developed social system, consequently most powerful ruling class.

5. Any struggle between nations-national struggles-is the expression of a struggle between classes using the nation in waging their disputes.

These are the generalizations; the practice is not as concrete. Social progress is uneven; nations do not develop simultaneously, although their development is along essentially parallel lines; remnants of the preceding social system persist into the new and affect events; a ruling class often disputes supremacy with its predecessor or potential successor, and is itself often divided into warring groups; nor is capitalism static, its various stages of development being a distinct factor and affecting the course of events. Then, again, the nation- a product of historical factors-becomes itself an historical factor, and at times must be considered as an historical category. But all the historical factors are synthesized into the dominance of class and the struggle of class against class, and are fundamentally determined by the interests of the class struggle. There is a play of forces- of their proportion and relation which offers a fruitful field for investigation to the Socialist historian. This task is beyond the scope of this article; our task is to indicate and suggest.

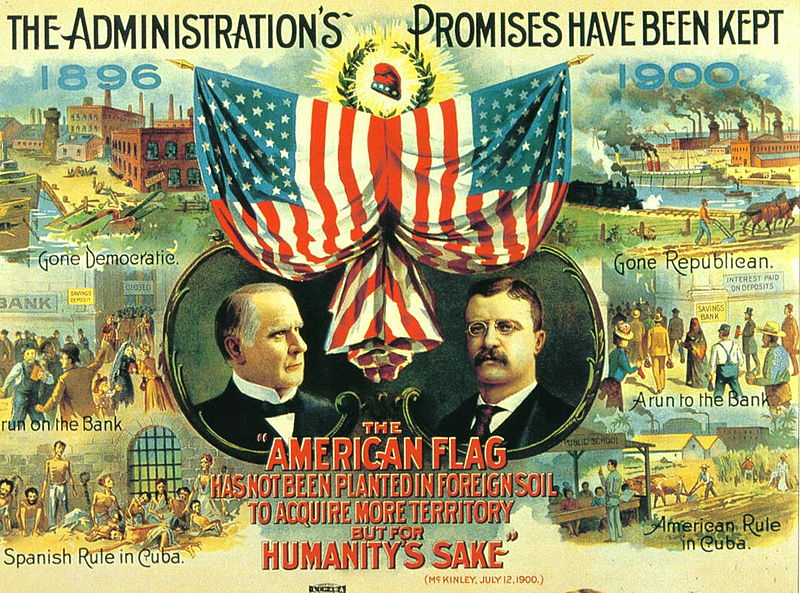

The series of bloody wars which signalized the advent of the bourgeoisie and the nation-state was essentially the expression of the class interests of the, bourgeoisie, in conflict with Feudalism. The struggles of many years between France and England, marked by the battles of Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt, were fundamentally a class struggle in the form of war between the rising bourgeoisie of England struggling for territorial conquest and markets, and the feudalism of France, the triumph of the yeomanry over the flower of the French nobility is symbolical of the character of the wars. It is true that England and France at this period had much in common, historically; both were at the era of territorial consolidation, politically the distinguishing feature of the formation of the nation; but England was much more advanced than France economically; her bourgeoisie had conquered a larger share of power, its commercial interests stronger; while in France feudalism was as yet unshaken by the bourgeoisie. The flourishing manufacturing interests of England were protected and encouraged by the government, and the extensive trade in wool with the manufacturing towns of Flanders was a direct cause of the wars. Undoubtedly, the wars were not purely capitalist wars; feudal interests were involved; but what distinguishes them from the wars of feudalism and gives them their distinctive historical character was the preponderance of bourgeois interests. The national struggles of the era of the Reformation were another expression of the bourgeois urge to power, and the expression in national form of the interests of the class struggle of the bourgeoisie.

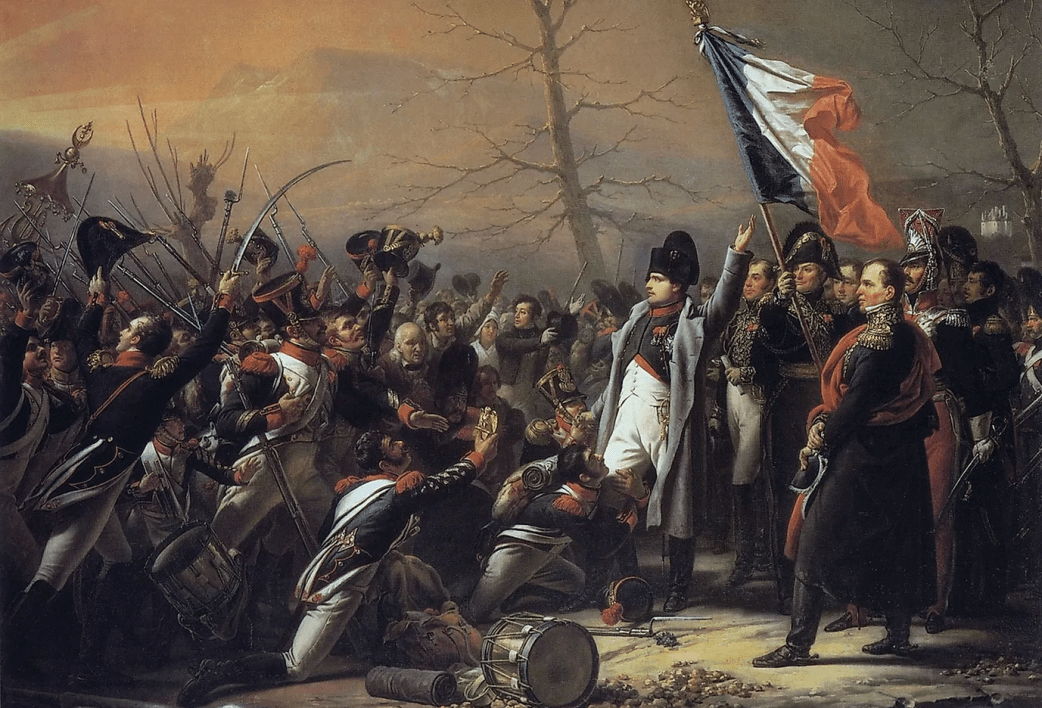

The wars of the French Revolution offer the finest illustration of the essentially class character of national struggles. These wars were an extension and continuation of the struggle waged by the bourgeoisie of France against the absolute monarchy and its feudal interests. Never was a nation as thoroughly dominated by its bourgeoisie as was the France of 1793 and Napoleon. The revolution that drastically overthrew the monarchy and its feudal relations struck a terrific blow at monarchy and feudalism throughout Europe. Clearly and absolutely the national struggles that followed were dictated by class interests-the class interests of the bourgeoisie, incarnated in Republican France, in conflict with the class interests of feudalism, represented by monarchical Europe. The class struggle of the bourgeoisie waged in France by means of revolution, was converted into a national class struggle waged by means of international war, emphasizing that national struggles are a form of manifestation of class struggles waged on the field of international politics. The revolutionary and Napoleonic wars were the death-grapple of two social-economic systems struggling for ascendancy. (1)

One feature of the Socialist theory of the class struggle is that the class struggle represents a struggle between a dominant economic system and its ruling class, and a rising economic system and its subject class. The national struggles cited were essentially of this character, struggles between feudalism and capitalism, each seeking social control. But not all national struggles are of this character, and the answer to this is that the class struggle theory admits and demonstrates that there are class struggles between rival groups of the ruling class itself. National struggles not susceptible of our original interpretation fall into this latter category. This is particularly true of national struggles to-day.

An important phase of contemporary Capitalism is the expropriation of the capitalist by the capitalist. In national economics, this expropriation proceeds by means of the concentration of capital.

But capitalism reaches a point where, along with other factors, this process of expropriation reaches a certain limit. Expropriation and concentration along national lines become insufficient; big capital and small capital strike a compromise in partial or complete State Socialism; and instead of the expropriation of the individual capitalist, there is the attempt to expropriate the capitalists of a rival national group by means diplomatic pressure, “spheres of influence” and war, -in short, Imperialism.

What confuses the problem of the nation in the eyes of many is the circumstance that general interests- social, cultural, ideological- are bound up with the nation, and that these interests are advanced or retarded by national struggles. But the Socialist admits that a ruling class develops certain cultural factors that are a permanent contribution to civilization. At the present moment, however, the greatest danger to these cultural factors lies in the perpetuation of the nation-the defense of the nation. In the measure that the nation becomes an instrument of Imperialism, the nation becomes reactionary, in much the same way as absolute monarchy, which at its inception served the interests of the bourgeoisie and progress, and later on menaced those interests. Imperialism denies the necessity of the democratic federation of nations, a task laid upon Capitalism by the historic process. Capitalism has generated the forces of internationality; it remains for Socialism to organize the forces effectively, into a world-state.

It is inconceivable that Capitalism should produce an actual unity of nations, which would pre-suppose the dissolution of the nation in its existing form. Identically as with parliamentary government, the nation is the particular expression of the interests of the capitalist class. The capitalist class finds its essential expression in the nation and parliamentary government; the proletariat in the world-state and industrial government. The working class struggle against Capitalism, accordingly, assumes the form of a revolutionary struggle against the nation and parliamentary government. The proletariat, as a revolutionary class, must project its own governmental expression, its own concept of the relations between nations, industrial government and the world state. The embryo of this expression is industrial unionism and international proletarian organization. This means a relentless struggle against the nation and its interests, and parliamentary government and its social manifestations.

1. The supremacy of Napoleon and the national risings which finally accomplished his overthrow, do not alter our interpretation. The Napoleonic struggle for world empire, while produced by the necessity of the prevailing situation, was pre-capitalistic in its purposes. Hence the struggle assumed a new form- the class interests and national interests of the bourgeoisies of certain parts of Europe fought against the Napoleonic menace to their interests. At this stage, the struggle is essentially between rival groups of the same ruling class; the wars between France and England at this period were of the latter character

THE Russian Socialist, Paul Axelrod, insists that a thorough historical study of the nation is indispensable for Socialist reconstruction after the war. This is an acceptance of the fact that our attitude to the nation is the decisive factor in the reorganization of the Socialist movement; and our attitude to the nation carries with it the reconstruction of our national and international policy and tactics, not simply in relation to war, but to the whole scope of the movement.

A mere historical study, however, is in itself insufficient; few Socialists would disagree, historically, about the significance of the nation as a creation of the bourgeoisie. The important point is a contemporary study of the nation and its role in social development, and the whole subject of the nation and parliamentary government within the nation. Parliamentary government is part and parcel of the nation, fundamentally one problem and one manifestation, and should be considered as such.

But even historically Socialists are not all in harmony in their conception of the nation. There is an assumption among some Socialists that, while the nation is the particular creation and form of expression of the bourgeoisie, the nation is just as important as the class and that the struggles of nations each with the other function as dynamically as class struggles. History refutes this assumption- national struggles are a form of manifestation of the class struggle.

The historical generalizations concerning this problem may be summarized as follows:

1. The nation is the expression of a particular social and economic system and the class representing that system.

2. The destiny of a nation is determined by the development of the economics of its social system and its ruling class.

3. Competing nations represent competing social-economic systems and ruling class interests.

4.The hegemony of a nation at any particular epoch represents the hegemony of the most highly developed social system, consequently most powerful ruling class.

5. Any struggle between nations-national struggles-is the expression of a struggle between classes using the nation in waging their disputes.

These are the generalizations; the practice is not as concrete. Social progress is uneven; nations do not develop simultaneously, although their development is along essentially parallel lines; remnants of the preceding social system persist into the new and affect events; a ruling class often disputes supremacy with its predecessor or potential successor, and is itself often divided into warring groups; nor is capitalism static, its various stages of development being a distinct factor and affecting the course of events. Then, again, the nation- a product of historical factors-becomes itself an historical factor, and at times must be considered as an historical category. But all the historical factors are synthesized into the dominance of class and the struggle of class against class, and are fundamentally determined by the interests of the class struggle. There is a play of forces- of their proportion and relation which offers a fruitful field for investigation to the Socialist historian. This task is beyond the scope of this article; our task is to indicate and suggest.

The series of bloody wars which signalized the advent of the bourgeoisie and the nation-state was essentially the expression of the class interests of the, bourgeoisie, in conflict with Feudalism. The struggles of many years between France and England, marked by the battles of Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt, were fundamentally a class struggle in the form of war between the rising bourgeoisie of England struggling for territorial conquest and markets, and the feudalism of France, the triumph of the yeomanry over the flower of the French nobility is symbolical of the character of the wars. It is true that England and France at this period had much in common, historically; both were at the era of territorial consolidation, politically the distinguishing feature of the formation of the nation; but England was much more advanced than France economically; her bourgeoisie had conquered a larger share of power, its commercial interests stronger; while in France feudalism was as yet unshaken by the bourgeoisie. The flourishing manufacturing interests of England were protected and encouraged by the government, and the extensive trade in wool with the manufacturing towns of Flanders was a direct cause of the wars. Undoubtedly, the wars were not purely capitalist wars; feudal interests were involved; but what distinguishes them from the wars of feudalism and gives them their distinctive historical character was the preponderance of bourgeois interests. The national struggles of the era of the Reformation were another expression of the bourgeois urge to power, and the expression in national form of the interests of the class struggle of the bourgeoisie.

The wars of the French Revolution offer the finest illustration of the essentially class character of national struggles. These wars were an extension and continuation of the struggle waged by the bourgeoisie of France against the absolute monarchy and its feudal interests. Never was a nation as thoroughly dominated by its bourgeoisie as was the France of 1793 and Napoleon. The revolution that drastically overthrew the monarchy and its feudal relations struck a terrific blow at monarchy and feudalism throughout Europe. Clearly and absolutely the national struggles that followed were dictated by class interests-the class interests of the bourgeoisie, incarnated in Republican France, in conflict with the class interests of feudalism, represented by monarchical Europe. The class struggle of the bourgeoisie waged in France by means of revolution, was converted into a national class struggle waged by means of international war, emphasizing that national struggles are a form of manifestation of class struggles waged on the field of international politics. The revolutionary and Napoleonic wars were the death-grapple of two social-economic systems struggling for ascendancy. (1)

One feature of the Socialist theory of the class struggle is that the class struggle represents a struggle between a dominant economic system and its ruling class, and a rising economic system and its subject class. The national struggles cited were essentially of this character, struggles between feudalism and capitalism, each seeking social control. But not all national struggles are of this character, and the answer to this is that the class struggle theory admits and demonstrates that there are class struggles between rival groups of the ruling class itself. National struggles not susceptible of our original interpretation fall into this latter category. This is particularly true of national struggles to-day.

An important phase of contemporary Capitalism is the expropriation of the capitalist by the capitalist. In national economics, this expropriation proceeds by means of the concentration of capital.

But capitalism reaches a point where, along with other factors, this process of expropriation reaches a certain limit. Expropriation and concentration along national lines become insufficient; big capital and small capital strike a compromise in partial or complete State Socialism; and instead of the expropriation of the individual capitalist, there is the attempt to expropriate the capitalists of a rival national group by means diplomatic pressure, “spheres of influence” and war, -in short, Imperialism.

What confuses the problem of the nation in the eyes of many is the circumstance that general interests- social, cultural, ideological- are bound up with the nation, and that these interests are advanced or retarded by national struggles. But the Socialist admits that a ruling class develops certain cultural factors that are a permanent contribution to civilization. At the present moment, however, the greatest danger to these cultural factors lies in the perpetuation of the nation-the defense of the nation. In the measure that the nation becomes an instrument of Imperialism, the nation becomes reactionary, in much the same way as absolute monarchy, which at its inception served the interests of the bourgeoisie and progress, and later on menaced those interests. Imperialism denies the necessity of the democratic federation of nations, a task laid upon Capitalism by the historic process. Capitalism has generated the forces of internationality; it remains for Socialism to organize the forces effectively, into a world-state.

It is inconceivable that Capitalism should produce an actual unity of nations, which would pre-suppose the dissolution of the nation in its existing form. Identically as with parliamentary government, the nation is the particular expression of the interests of the capitalist class. The capitalist class finds its essential expression in the nation and parliamentary government; the proletariat in the world-state and industrial government. The working class struggle against Capitalism, accordingly, assumes the form of a revolutionary struggle against the nation and parliamentary government. The proletariat, as a revolutionary class, must project its own governmental expression, its own concept of the relations between nations, industrial government and the world state. The embryo of this expression is industrial unionism and international proletarian organization. This means a relentless struggle against the nation and its interests, and parliamentary government and its social manifestations.

NOTE

1. The supremacy of Napoleon and the national risings which finally accomplished his overthrow, do not alter our interpretation. The Napoleonic struggle for world empire, while produced by the necessity of the prevailing situation, was pre-capitalistic in its purposes. Hence the struggle assumed a new form- the class interests and national interests of the bourgeoisies of certain parts of Europe fought against the Napoleonic menace to their interests. At this stage, the struggle is essentially between rival groups of the same ruling class; the wars between France and England at this period were of the latter character.

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1916/v4n02-jan-15-1916.pdf