It has been remarked that Mary E. Marcy seldom wrote for women as an audience. I believe this is false, Mary wrote for workers and as such women and their issues feature in nearly all of her writings. Here, however, she speaks specifically to women in a wonderful essay combining a number of her many interests. Reversing the accusation that ‘Socialism would break up the home,’ she traces the changes to what we might now call ‘social reproduction’ brought by capitalist industrialization. Introducing skills and tools lost in the process of proletarianization.

‘One Hundred Years Ago’ by Mary E. Marcy from International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 12. June, 1912.

IT WAS not until we knew Grandmother Hopkins, a beautiful old lady of eighty-eight, who had come to make her home with relatives in the city, that we realized what invention and the factory system have done to the old-fashioned home.

She had grown a little childish but her pain and wonder over the ways of flat dwellers and “roomers” was always accompanied by a flow of words on the good old days and only to hear her was a liberal education on the pioneer days in the Central States.

The switch with which we turned on and off the electric lights, the marvels of the gas range and steam heat would always start her off on reminiscences of the great old fireplaces and of candle making.

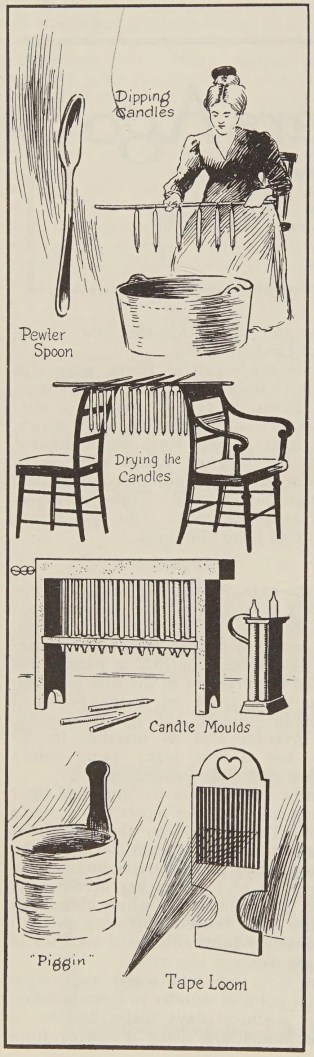

The candle wicks, Grandmother told us, were made of loosely spun hemp, tow or cotton, sometimes even of milkweed. Six or eight long strands of the tow were usually tied to a stick and were dipped into great kettles filled with hot tallow. Later, when the settlers raised bees, wax was often used. Candle making was the work of the women of the household, and the task was an arduous one. The long wicks had to be alternately dipped into the hot tallow or wax and allowed to cool, the candles increasing in thickness with every operation. Feeding the fire alone was a job of no mean proportion. All through the year the women hoarded every ounce of deer suet, moose fat, bear grease and tallow for the time of the annual candle making.

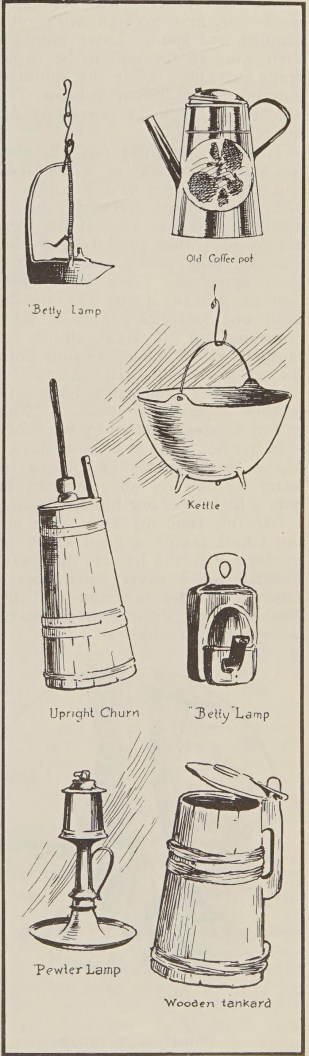

Homemade pewter lamps were also used in Grandmother’s day. These were mere bowls or cans containing a narrow spout from which hung wicks which, when lighted, gave forth an unpleasant smoke but a glow vastly superior to candlelight. Fish and other homemade oils were first burned. These were prepared by the women. This was before the day of lamp chimneys.

Fire.

In the days of the early settlers it was a family catastrophe when the fire went out. But in Grandmother’s time flint, steel and tinder were recognized household necessities. In 1827 a patent was granted the inventor of the first matches. These were made of strips of wood dipped in sulphur, and ignited readily. The inventor sold 84 matches for 25 cents, but it was many years before matches came into general use.

Candle making, fire building and light striking are no longer a part of “woman’s work.” They have been abolished from the home. Gas, steam and electricity are at hand ready to do our bidding. Even the making of matches has become one of the great industries, where thousands of girls and women operating modern machines produce millions of matches in a single day.

The hot and cold water taps were another point of wonder to Grandmother. In her girlhood days water had to be carried sometimes long distances from springs and heated in great pots over the fireplace.

The Pennsylvania Dutch had the first stoves used in America. The first stove was built into the house, three sides being indoors, while the stove had to be fed from the outside. As the men worked out of doors a goodly portion of the time, the fire tending fell to the lot of the women. I doubt not but many of them could wield an ax with any of the men.

As cattle increased, the duties of the dairy grew. There came butter making; and cheese making was an unending care from the time the milk was set over the fire to warm and curdle, through the breaking of the curds into the cheese baskets, through shaping into cheeses and pressing in cheese presses, and placing them on the cheese ladders to be constantly turned and rubbed.

Soap Making.

Soap making time came in the fall, and meant more work for the housewife. Even the lye had to be manufactured from wood ashes at home. And there were geese to be picked three or four times a year, for everybody slept on feather beds in those days.

I remember one of grandmother’s stories of an old-time neighbor who burned down a deserted house merely for the sake of the few nails used in its construction. Nails were one of the most valuable of all the commodities in her grandmother’s day.

November was the appointed killing time. Of refrigeration there was none and fresh meat lasted only a short time in warm weather. Choice pieces were sometimes preserved in cool springs for a little while but almost all meats had to be promptly pickled and salted away for preservation. Rolliches and head cheeses were made at killing time; lard was tried and tallow saved.

In the winter might be found in the homes of every good housewife, hogsheads of corned beef, barrels of salt pork, tubs of hams being salted in brine, tonnekins of salt fish, firkins of butter, kegs of pigs feet and tubs of souse. And there were head cheeses, strings of sausage, very highly spiced to preserve them, jars of fruit, bins of potatoes, apples, turnips, parsnips and beets.

The kitchen, or living room, was constantly hung with strings of drying apples, onions, rounds of pumpkins and peppers. Sugar was very scarce and its place was taken by pumpkins and very soon by honey, till maple syrup and maple sugar were discovered.

Today some women still preserve the fruit and vegetables for their own families. This is no longer a difficult matter. A telephone message brings the required material from the nearby grocer, also jars to be hermetically sealed. The ingredients are ready to hand, prepared by the thousands of men and women working in huge factories all over the world. Fire is brought up to our very table. We have only to turn it on. But the woman who now does preserving at home is the exception. Little by little the factories have taken up this branch of “woman’s work” and it is now much cheaper to buy factory canned goods than to do the work in the home. Perhaps our grandmothers who suffered through the hot summer days over blazing stoves are not sorry to see this branch of home life destroyed by the factory system.

Spinning and Weaving.

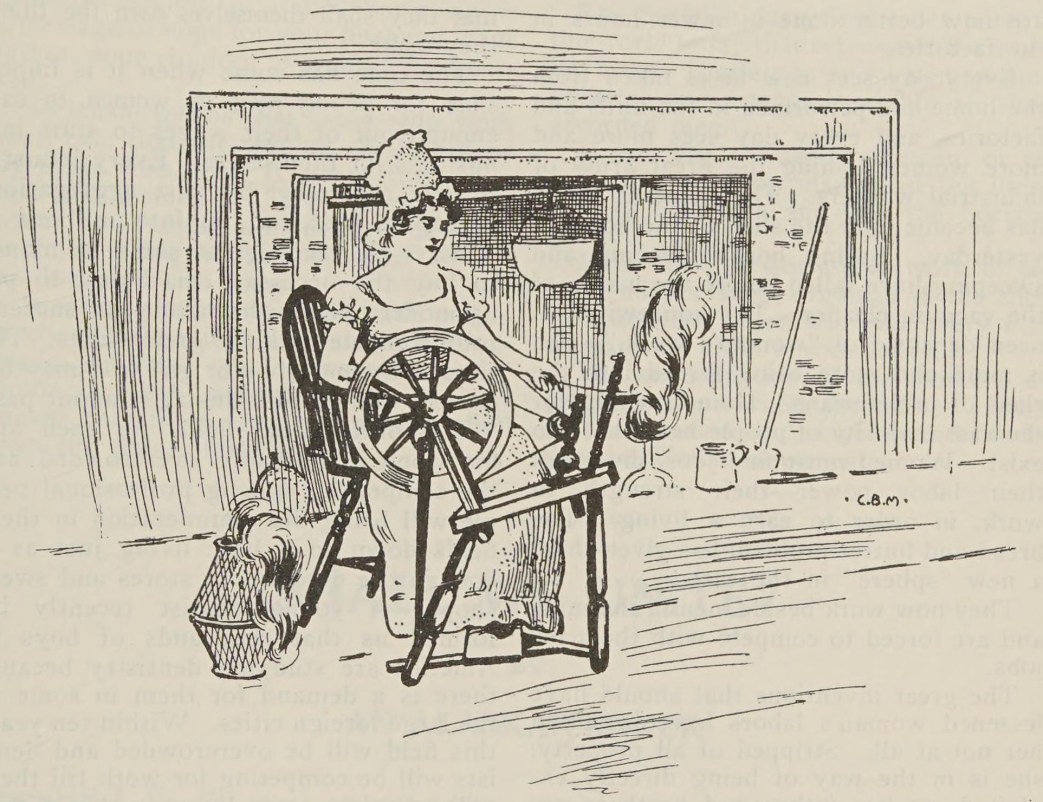

Almost within our fathers’ time, every farmer and his sons raised wool and flax. His wife and daughters spun them into yarn and thread. When the flax plants were only three or four inches high they were weeded by the women and children who were compelled to work in their bare feet in order to avoid crushing the young stalks. Usually men prepared the flax and “broke it,” while the girls, working their feet on the treadle, spun the fiber into an even thread. The thread was then wound off into reels or skeins.

These were bleached by being laid in water for four days, the water being constantly changed and the skeins wrung out. Finally they were “bucked,” that is, bleached in ashes and hot water for a week or more, after which came a grand rinsing, washing, drying and winding on bobbins for the loom. All this labor in the bleaching process was not by any means the end of the operations.

Steadily wool production increased. The fleeces had to be gone over by the women with care, and all pitched and tarred locks, brands and beltings were cut out. But they were not lost. The cuttings were spun into coarse yarn.

Dyeing.

The white locks were carefully loosened and separated and tied into net bags to be dyed. Indigo was the favorite blue dye. Cochineal and logwood and madder made beautiful reds. Bark of the red oak or hickory made pretty browns and yellows. The flower of the golden rod when pressed of its juice, mixed with indigo and added to alum, made a bright green. Sassafras bark was used to secure a rich brown and orange

The next process was carding. The wool was first greased with oil, then combed and spun. Later families sent their wool to the mill to be carded by crude machines, while the spinning and weaving was still done at home. This is, we believe, still the prevailing method in Ireland.

The same primitive methods prevailed for a long time in the cotton industry. But the invention of the cotton gin in 1792 soon made necessary the use of machinery to take care of the increased supply of cotton produced by the gin. The spinning jenny and power looms soon appeared. More work, formerly performed in the home, was now done in mills and factories. This meant more “breaking up” of what all our grandmothers’ called home. Cotton cloth was for a time was still printed, colored, or “stamped” by hand, in the home. Grandmother remembers wearing “beautiful cotton dresses” printed by her mother.

In her home life in colonial days, Alice Morse Earle quotes as follows from a letter written by an American farmer only a little over one hundred years ago:

“At this time my farm gave me and my whole family a good living on the produce of it and left me one year with $150.00, for I never spent more than $10.00 a year for salt, nails and the like. Nothing to eat, drink or wear was bought as my farm provided all.”

About the same time Abigail Foote set down her daily work in this wise (Home Life in Colonial Days):

“Fix’d gown for Prude. Mended mother’s riding hood. Spun thread. Carded tow. Spun linen. Hatchel’d flax with Hannah. Worked on cheese basket. Spooled a piece. Milked cows. Spun linen. Did 50 knots. Made broom of Guinea wheat straw. Carded two pounds of wool. Spun harness twine.”

Beside the work of cooking and taking care of the home generally the women of grandmother’s time were in charge of the dairying, raising of small stock, combing, carding, spinning, weaving, knitting, sewing, pickling, preserving, salting, soap and candle making. All stockings and mittens were knit at home till 1850, when a patent was granted for wool weaving machines. It was a good many years later that machine weaving became general

Women made every article of clothing worn by the entire family except sometimes, the shoes. She made bonnets for the girls and hats and caps for the men. She wove the shawls worn by everybody and invented the first straw hat. When there were carpets, these too were the work of her hands.

In grandmother’s day the home was the industrial unit. Every man, woman and child knew how to produce things for the needs of the family. Nothing was specialized beyond the family. The individual farm was almost sufficient unto itself.

Something has destroyed the home and home life that our grandmothers knew. It is enough that we conjure up a picture of the old ways and compare them to the lives of the flat dwellers, the boarders and roomers of today. More proof is not needed. The old-fashioned home has been destroyed, is being further destroyed by the invention of new machinery and the progress of specialized factory production.

From the very first the machine carding of fleece was so cheap that farmers were constrained to send this work to be done in the mill. Then came machine spinning and weaving. At every step it became evident that home labor could be more remuneratively employed in other branches rather than by doing these tasks performed at such low cost in the mills. For a long time all the family clothing was still made in the home, where the sewing machine helped to reduce the drudgery of the housewife. And in our own time every article of wearing apparel can be purchased readymade at prices so low that homemade clothes have become almost a thing of the past. Cheapness has battered down the wall of the farmer’s prejudice and gradually he has permitted almost every branch of industry to be taken from his home to be done in the mill and factory, while he has set the members of his family to specializing in lines where the pay is better. It was never possible for the seller of homemade products to compete with the mill or factory machine commodities for long. Farm machinery has steadily lessened the work of the men upon the farm. One man can today, by the use of modern machines, accomplish the work that ten men did formerly under the old methods. But the young men and women have followed their old work into the cities, into the woolen and cotton mills, into the match factories, and packing houses. Many of them no longer have even their meals in their own homes. Great armies of restaurants and cafes have sprung up everywhere, where people may dine for less than it would cost to cook at home.

Laundries there are too—”breaking up” another branch of the old time “home.” With one dozen sheets washed and ironed by machine for 25 cents came the beginning of the end of the old back-breaking wash-tub days. Monday, or “wash day,” has lost its old-time significance. It is just like any other day.

Gone are the candle-making seasons, the wood splitting and fire feeding and water carrying times. Of home soap-makers we have none and few of us would even know how to make lye if we had to. Steam heat, electric lights, bakeries, laundries, restaurants, ready-to-wear clothing have destroyed, little by little, year by year, the classic institutions of the old time home. Tasks that it took our grandmothers many days in the doing are now better done in fewer hours in the factories.

Every day sees new tasks taken from the home and performed in the mills and factories, and every day sees more and more women joining the great army of industrial workers. The home of today has become only the shell of the home of yesterday. Spring house cleaning and sweeping have fallen before the march of the vacuum cleaner. The housewife has been deprived of “woman’s work.” She is more and more being forced into the class of proletarians. Home owning for the vast majority of people has ceased to exist. Women must find jobs, must sell their labor power—their strength to work, in order to earn a living. The bread-and-butter problem has given them a new “sphere” in the factory.

They now work beside men in the mills and are forced to compete with them for jobs.

The great inventions that should have lessened woman’s labors have benefited her not at all. Stripped of all property, she is in the way of being directly exploited, as her father and brothers are being exploited. In order to earn a living she grinds out profit for some capitalist.

The great factories, and modern machines that perform, with very little expenditure of human labor, the arduous tasks that formerly were hers, do not bring ease or comfort or, plenty, to her. For these tools, these great machines by which clothes and food and other commodities are produced, are owned by a few men and women who do not operate, or use them.

Because there are always thousands of unemployed men and women seeking for jobs, wages are always driven down to the bare cost of living. For the bosses, the factory and mill owners, always buy labor power or working strength where it is cheapest. All the clothing, the shoes, hats, food, etc., that the workers produce are kept by the factory and mill owners. They should be the property of those who do the work. This is the aim of Socialism. It proposes that the men and women who work shall own the factories, mills, mines, railroads and the land, and that they shall themselves own the things they make.

The time has come when it is impossible for young men or women to save enough out of their wages to start into business for themselves. Every industry is now controlled by vast aggregations of capital that run up into millions of dollars. It takes great sums of money to buy the necessary machines, to put up modern plants that alone can successfully compete with the great trusts. The time of the poor boy or girl who may become a captain of industry is about past.

The professional fields for men and for women are badly overcrowded and the competition among professional people will bring the remuneration in these fields down to a bare living just as it does in the department stores and sweat shops. A young dentist recently informed us that thousands of boys in America are studying dentistry because there is a demand for them in some of the large foreign cities. Within ten years this field will be overcrowded and dentists will be competing for work till there will be only a scant living in this profession for any of them.

It is too late to go back to Grandmother’s way even if we wanted to. There is no more free land. The capitalist system under which we live draws our sons to the cities to earn a living, our daughters into the factories, our husbands into the mines. It sends us into the mills to make cloth.

The capitalist system has broken up the old-fashioned home and scattered it to the four corners of the earth for the sake of profits. Our only hope lies in Socialism.

There is no hope for the propertyless young man or woman becoming independent today. There is no one to assure you that you and your husband shall have steady work—that your children shall be able to earn three square meals a day. This is the task of Socialism.

Whether or not you are one of the fast-decreasing number of housewives today, or whether you are a wage slave directly exploited in the factories, mills or department stores, your home broken up, or your hope of a home destroyed by the capitalist society of today; Socialism is a message of hope for your husband, your father, your children as well as for yourself.

Socialism means that those who work shall eat; that the reaping shall be done by those who sow. It means that every man and women in the world shall have equal and ample opportunity to work without being robbed of most of his product by a rich boss.

It means that the workers shall collectively own the mines, mills, factories, railroads and land—all the instruments for producing the necessities of life. It means that these men and women shall own the things they produce.

The Socialist party is the one party in the world today that represents the working class. It offers to every woman equal political and economic rights to those accorded men.

If you are a working woman, or the wife of a working man, read the literature of Socialism and join the Socialist party.

Meanwhile, if you are at work in factory, mill or shop, organize in the shop. An industrial union will give every man, woman and child a vote today.

The emancipation oi the workers depends on the workers themselves. Write for information on Socialism and the Industrial Union movement.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n12-jun-1912-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf