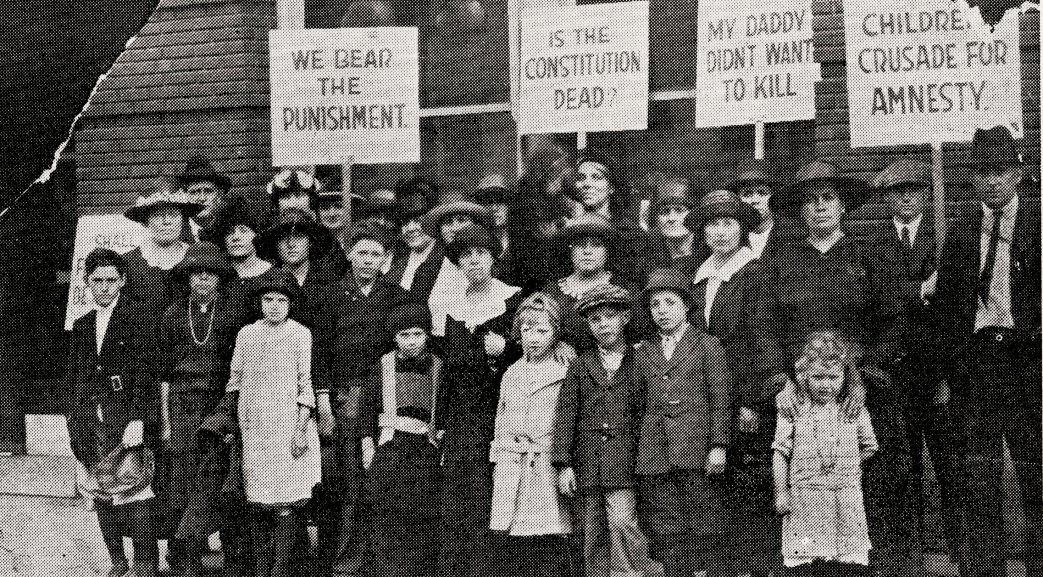

Gurley Flynn looks back two decades to the repression of the radical as the U.S. went to war in 1917 that sent tens of thousands to prison or deportation, and the ‘Children’s Crusade’ for amnesty organized by Kate Richards O’Hare.

‘The Last War’ by Elizabeth Gurley Flynn from Labor Defender. Vol. 13 No. 4. May, 1937.

BIG BERTHAS at Home: A grim account of what happened to civil rights during the last war with the Children’s Crusade to Washington as its climax.

We marvel at the temerity of peasants who farm on the sides of Mt. Vesuvius regardless of how often it erupts, and those who live in earthquake zones where known faults exist in the crust of Mother Earth. But there is nothing can be done and fatalism is inevitable, especially where poverty compels. Those who turn a deaf ear to the experiences of the past war and say, “It can’t happen again,” are much more foolhardy. They court sudden disaster. Preparations afoot today will make the last war a mere dress rehearsal. We live calmly on a man made volcano that may erupt any day. Let us give a backward glance to twenty years ago it will be a warning to impending dangers, in a final world conflict.

War was declared on April 6, 1917. The Espionage Act was passed on June 15, 1917. It was suspended on March 3, 1921, the last day of Wilson’s administration, over two years after the armistice, to be reinvoked whenever the United States is at war.

Accurate figures are not available of its victims during the four years. Between 3,500 and 4,000 members of the I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World) were arrested. There were 1606 trials up to July 1918. Men and women, were third-degreed; held under prohibitive bail; meetings were brutally dispersed; halls and offices destroyed; newspapers suppressed; postal rights denied. Letters were stamped “Undeliverable under the Espionage Act” and returned to the sender; mob violence spread through the nation.

Those arrested were Socialists, I.W.W.’s and sundry radicals who were opposed to the war or whose labor activities attacked war profiteers. The war furnished the pretext to accomplish what the big interests had vainly attempted to smash the I.W.W. Fifty thousands lumberjacks, and 40,000 miners were on strike under its banner in Arizona, Montana and the northwest by June 1917. A howl went up: “The I.W.W. is paid by German gold to hamper the war.” (This was before Russian gold became the great bugaboo!) The 8-hour day and wage increases, were forced from the Lumbermen’s Association. On the wild hysteria fomented against the strikers, 1200 miners of Bisbee, Arizona, were deported in July 1917 by 2,000 company gunmen, to the desert of New Mexico and left there to starve. Frank Little, crippled organizer, was lynched in Butte, Montana, by vigilantes in August 1917.

The western workers were greatly incensed by these outrages and the employers, desperate to safeguard their huge wartime profits against further demands, appealed to the Federal government. The Espionage Act was the Big Bertha trained on the I.W.W. Tons of literature were confiscated and wholesale raids made. Three major conspiracy cases at Chicago, Ill., Kansas City, Kans., and Sacramento, Cal., resulted in the convictions of 166 organizers, editors, officials and members active in the basic western industry. Offenses consisted of opposition to war; regular union activities; membership and in some cases, past association only, with the I.W.W.

Some individual cases were particularly flagrant. Clyde Hough, a young man arrested on June 6, 1917, for refusing to register, was in jail when the Espionage Act was passed. He was re-arrested, convicted in Chicago of its violation and sentenced to Leavenworth for five years. His I.W.W. card was the sole evidence.

Eugene V. Debs, beloved Socialist leader, went to Atlanta for speaking in defense of others and demanding workers’ referendum on war. Kate Richards O’Hare, Socialist lecturer, was sent to Jefferson City Prison for a speech she had made innumerable times without molestation. Dr. Marie D. Equi of Portland, Ore., was convicted after the Armistice for her defense of I.W.W. prisoners and her organizing work and sent to San Quentin prison for a year. John S. Randolph, was convicted in Auburn, N.Y., also under the Espionage Act, after the Armistice was signed, for expressing his sympathy with Debs.

The trial judge questioned him in a friendly manner and then said he had intended to give Randolph a year on the verdict of the jury but on the views he had expressed to him in the court-room, he gave him a ten year sentence in Atlanta Prison. I regret that space here forbids recording the innumerable men and women, who like those mentioned, were cruelly and unjustly dealt with during those terrible years.

In addition to civil prisoners, there were 450 C.O.’s (conscientious objectors) who had been judged “insincere” by a Board of Inquiry and turned over to the military authorities for court martial as “disobedient soldiers.” One member of the board was Harlan J. Stone, now on the U.S. Supreme Court. He is described by Ernest L. Meyer, now of the N.Y. Post, then one of the C.O.’s as “popping startling questions with disconcerting rapidity,” at men who were weakened by torture and hunger at the camps. They were sent to the military Disciplinary Barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Alcatraz, and Fort Douglas for long sentences.

Horribly brutal treatment was inflicted on the C.O.’s to break their will, especially at Camp Reilly commanded by Major General Leonard Wood. One young man, Ernest Gellert, shot himself at Camp Meade, to prove his sincerity and that lack of courage to die, was not the reason for his attitude. The three Hofer brothers, religious objectors, died after torture at Alcatraz including beating by the Chaplain, and solitary in cold cells at Leavenworth. Their bodies were sent home clad in the uniforms they had rejected in life. Frank Burke, originally sentenced to 25 years died from similar treatment in prison.

In February 1919, three months after the Armistice, with 100 C.O.’s still in Fort Leavenworth for long sentences, 2,300 men went on the famous folded arm strike, a brave act when one remembers there were 4,000 soldiers at the Fort. It was called off when the Commanding Officer, Col. Rice, agreed to go to Washington on their behalf. The last 31 were released Nov. 23, 1920, two years after the war was over.

But the civil prisoners fared worse. Four years after the war was ended, there were still 71 I.W.W.’s and 21 others still in prison, mostly members of the tenant farmers’ “Workingclass Union” of Texas, Arkansas and Oklahoma, who had resisted the draft. As a final appeal, “one that could not be thrown in the waste basket,” the Children’s Crusade was organized by Kate O’Hare.

A party of 37, including the aged mother of Clyde Hough, 22 children and 11 wives of prisoners arrived in Washington on April 29, 1922. They had visited many cities en route, to tell their story and collect the expenses of the trip. They were a moving and heart-rending group. But genial President Harding was busy entertaining Lord and Lady Astor and refused to see them. They picketed the White House for a short time, until finally 16 of the tenant farmers were released, and others occasionally, until Christmas 1923 when President Coolidge released the last 31, five years after Italy, France, Belgium and England had released all similar prisoners.

The grim drama was over except for one final significant act. At Christmas 1933, President Roosevelt restored citizenship to all wartime offenders, a tentative recognition of the status of “political prisoners” for which the I.L.D. is now carrying on a legislative campaign.

Now, in 1937, twenty years after this gruesome tale began, the Army and Navy presents war plans, sponsored by the Chairman of the Military Affairs Committee of both Senate and House, known as the Sheppard Hill Bill and the Industrial Mobilization Plan. It has well been named a “Blue Print for Fascism.”

This is a serious menace to democracy, the destruction of unions and their gains and all civil rights. It must be fought and defeated. There shall be no large scale repetition of 1917 and 1918.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1937/v13-%5B11%5Dn04-may-1937-orig-LD.pdf