The economic crisis caused by the wars in the Balkans of the 1910s will pale in comparison to the coming European war says prolific Marxist historian Mikhail Pavlovitch, in 1913 living in Parisian exile.

‘Financial Aspects of the Balkan War’ by Mikhail Pavlovitch from New Review. Vol. 1 No. 4. January 25, 1913.

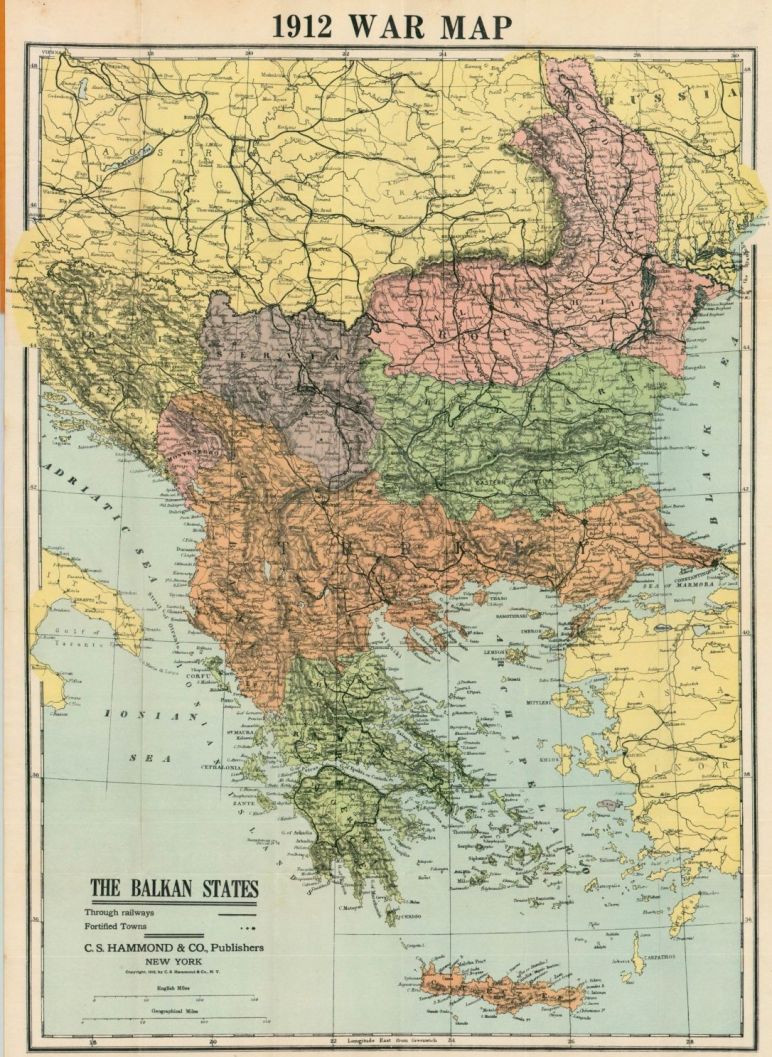

On October 8, 1912, Montenegro, the very smallest of the Balkan States, with a population of only 250,000 inhabitants, declared war upon Turkey. On the following day, before the hostile armies had even met, there lay around the building of the Paris Stock Exchange, dead and heavily wounded, with financial bulletins in their hands instead of guns, thousands upon thousands of large, medium and small stockholders. These had invested their savings, small and large, in all sorts of French and foreign government and industrial securities, among which were very many which seemed to have absolutely no relation to Balkan affairs.

During the last few years many economists have repeatedly insisted that France is the richest country in the world, that her gold reserve exceeds considerably the gold reserve of other countries, that her enormous metal reserve removes the possibility of a panic in France in case of any international shake-up. The French Stock Exchange seemed a sort of financial Gibraltar which feared no onslaught. Only last year a French economist, Count Saint Maurice, pointed out the financial power of France and showed that her gold reserve put her in a privileged position in comparison with other countries. Saint Maurice states with great satisfaction that the gold reserve of the Double Alliance, i.e., Russia and France, is over one and a quarter billion dollars, while the whole gold reserve of the Triple Alliance equals little more than six hundred million dollars, or half as much. In an article by me published toward the end of 1911, I proved to what extent the optimistic deductions concerning the unlimited financial power of France were unfounded. Concerning all European powers without exception, I wrote: “One can say that each one of them resembles a sick man suffering from rheumatism, whose every motion causes unspeakable pain. In case of war or any serious international complications, neither France nor England would occupy any specially privileged position in comparison with Germany.”

The events which took place on the Paris Stock Exchange the day after the unceremonious king of Montenegro, not considering in any way, according to his own admission, the interests of European capitalists, challenged Turkey, serve as illustrations of the above thesis. On October 9, French government securities were already lower than 90, and then fell to 89.95. In the course of the last twenty-two years the French financial world had not witnessed similar phenomena. Only on May 19, 1890, did the quotations stand at the same level. Even in the panic of February 9, 1904, caused by the Russo-Japanese War, the quotation of French exchange stood at 94, while at the time of the Agadir incident, July 6, 1911, it stood at 94.40. But the fall of French government securities did not now stop at 89.95. In three days more they stood at 87 and in three weeks from Sept. 20 to October 1, 1912, the holders of French securities lost by the depression of the Exchange exactly two hundred million dollars (one billion francs). It is not hard to imagine what happened with other securities. Paris bank stock fell 184 points; Credit Lyonnais, 115 points; Omnibus Co., 107 points; Thomson-Houston, 107 points; Suez Canal, 437 points.

Although there seems to be no relation between the company of Paris omnibuses, the Subway (Metropolitan!), the gas and electric companies, with the king of Montenegro, they too suffered. All stocks fell. People lost those few days entire fortunes, and there were cases of suicide. The French papers, which so often in past years insisted on the stability of the Paris Exchange, were compelled to write articles under the headings, “Panic on the Exchange,” “Financial Hecatombs,” “Catastrophe on the Exchange.” This rapid account of the financial upheaval which France underwent at the first alarming signal in the Balkans, frees me from the necessity of dwelling on the Berlin, Vienna, St. Petersburg and other exchanges. If the first shots fired on the Montenegrin frontier shook the foundations of the most formidable fortress of the financial world, it is not hard to guess what happened, in other countries. Even in the small Spanish city of Bilbao, the existence of which is known to probably no more than a few dozen Montenegrins, local holders of stocks of all sorts lost, according to the communications of financial newspapers, in the single day from October 8 to October 9, three hundred thousand dollars.

Therefore we can easily imagine what will happen in case of a European war. Let us take for example France herself. Her capital, placed in Turkish loans and various railroad and other enterprises of the Ottoman empire, equals $400,000,000, her trade with Turkey equals (1910) $33,600,000, but the figures of the trade of France with Germany are ten times greater, i.e., $332,000,000 (1910). And how many French millions are in German enterprises, and vice versa? What perturbations would a Franco-German war bring about in the economic life of both nations!

If a war should break out between the Triple Alliance (Austria, Italy and Germany) and the Triple Entente (Russia, France, England), hitherto unforeseen catastrophes would devastate all Europe. The Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente would have to mobilize against each other more than twenty million men, according to official data: Germany 3,600,000 soldiers, England 1,500,000, France 3,400,000, Italy 2,800,000, Austria-Hungary 2,600,000, Russia 5,000,000, a total of nearly 21,000,000. Each day of war would cost Europe, counting only the expenses of maintaining the armies, from fifty to seventy million dollars. Besides, trade would stop for the reason that the railroads would transport only soldiers, cannon, artillery supplies, cartridges, and ammunition for the armies, and would refuse to carry ordinary freight, because there would not be cars enough for the demands of war. Banks would fail, factories would close for the reason that so many working men would be called to arms. And so, having begun a European war, the bourgeoisie itself would actually decree a general strike, and in a form most disastrous to the capitalistic structure of society. That would be the beginning of a social revolution. But the bourgeoisie understands right well the results of a European war, and therefore fears it so.

The great depression of government and industrial securities in connection with Balkan occurrences, the heavy economic disturbances in Russia, Austria and all Europe, caused by the war of small Slavic kingdoms against Turkey, entirely refute those economists who, basing their hypotheses on the results of the Russo-Japanese war, tried to prove the groundlessness of “socialistic theories” concerning the inevitability of unforeseen economic catastrophes in case of a European war. But to cite the Russo-Japanese campaign as an example is wholly misleading. It was, so to speak, a “colonial war,” one that was waged in a domain lying not only beyond the borders of both hostile countries, but away from the great commercial routes and the industrial centers of contemporary world-economy. It is evident that the results of such a war could not be particularly grave in Germany, France, Austria, etc. On the contrary, that war benefited some branches of European industry, furnishing clothing, boots, provisions and war supplies to the fighting armies. But a war in the heart of Europe–well, look at the effects of the short and small Balkan war!

The New Review: A Critical Survey of International Socialism was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. Bases in New York it declared in its aim the first issue: “The intellectual achievements of Marx and his successors have become the guiding star of the awakened, self-conscious proletariat on the toilsome road that leads to its emancipation. And it will be one of the principal tasks of The NEW REVIEW to make known these achievements,to the Socialists of America, so that we may attain to that fundamental unity of thought without which unity of action is impossible.” In the world of the East Coast Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Robert Rives La Monte, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Arturo Giovannitti, Harry W. Laidler, Austin Lewis, and Isaac Hourwich as editors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 and lead the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. International writers in New Review included Rosa Luxemburg, James Connolly, Karl Kautsky, Anton Pannekoek, Lajpat Rai, Alexandra Kollontai, Tom Quelch, S.J. Rutgers, Edward Bernstein, and H.M. Hyndman, The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable and invaluable archive of Marxist and Socialist discussion of the time.

PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1913/v1n04-jan-25-1913.pdf