A mass strike by New England textile workers in 1922 is hampered by division as over a dozen different, often competing, unions are involved.

‘The Revolt of the Textile Workers’ by W.E. Vinyarn from Labor Herald. Vol. 1 No. 2. April, 1922.

THE greatest strike witnessed in the textile industry began on January 23rd. Starting in the Pawtuxet Valley, Rhode Island, it extended quickly to Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire and Vermont; like a great wave this demonstration of protest of the textile workers spread until it involved upwards of 50,000 cotton workers.

The cause of the revolt lay in the terrible working conditions in the industry. For generations the disease-breeding mills in the cotton industry have sucked the life of the workers, and greedy employers have ground. down wages to bare subsistence level and below. Six months ago the wages, already at a starvation point, received a general cut of 20%. This cut into their very hearts was accepted by the timid and oppressed workers without a struggle. In January, emboldened by their previous success, the employers announced another cut of 22% and an increase in hours from 48 to 54 per week. This was the straw that broke the camel’s back. was the signal for the strike.

In the little village of Natick there was a local of the Amalgamated Textile Workers of America. They succeeded in striking the big mill of the B.B. and R. Knight Company on the morning the cut was to go into effect. The strikers then marched to the two adjoining mills and struck them. A speaker was sent from the Providence local to the mass-meeting of the strikers that afternoon. “The other workers are as anxious as you to resist this cut. Go ask them to join you,” he said. The “Iron Battalion” was formed forthwith. The other mills were called upon and the whole Pawtuxet Valley was tied up 100% in a few days. The A.T.W. of A. enrolled thousands of members.

In the adjoining Blackstone Valley things went slower–not that the rank and file of the workers willed it so, but the red tape of officialdom held them in check. In that valley the United Textile Workers of America. had a few locals of different crafts or departments. These naturally wanted their national officers to take the helm. But the International President was taken sick, and other “important” incidents happened to hinder action, so that nearly two weeks went by before the mills in the Blackstone Valley started to come out Their strike was not so prompt and clear cut as in the Pawtuxet Valley, but eventually they tied up all the mills and established a solid front.

The 12,000 workers in the Amoskeag Mills at Manchester, N.H., which are organized in the United Textile Workers, shortly afterwards joined the strike. Numerous other mills followed, until finally the cotton strikers totaled more than 50,000.

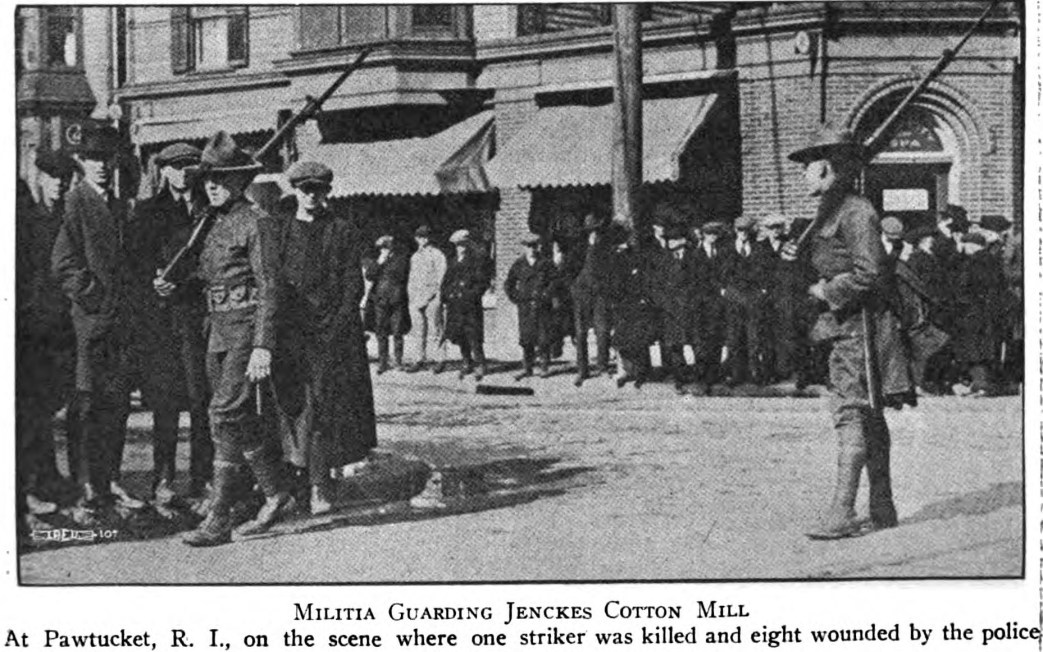

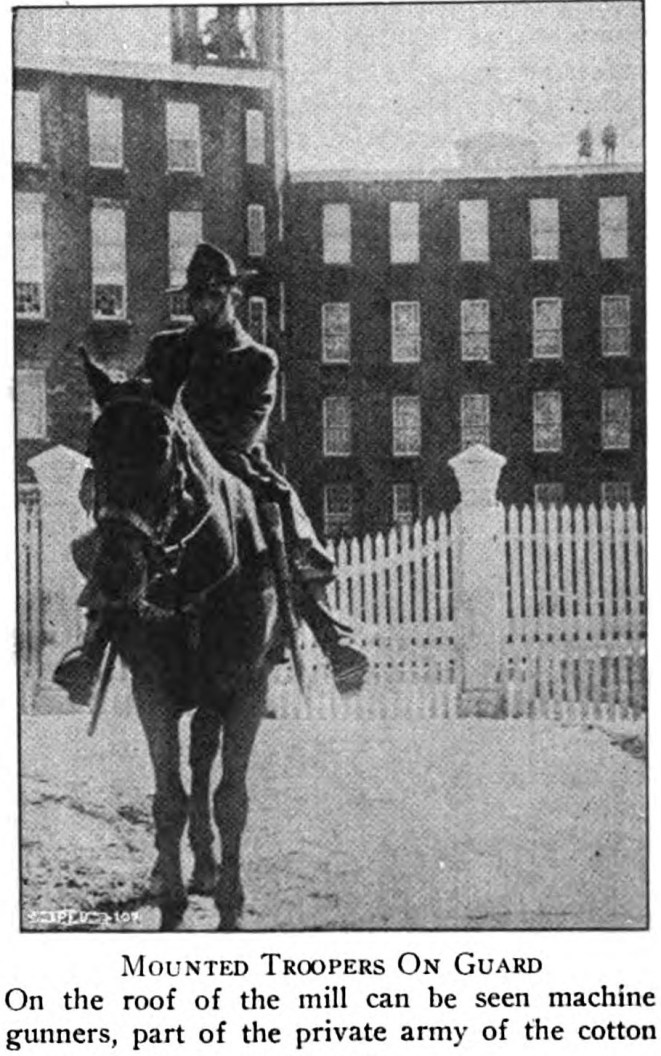

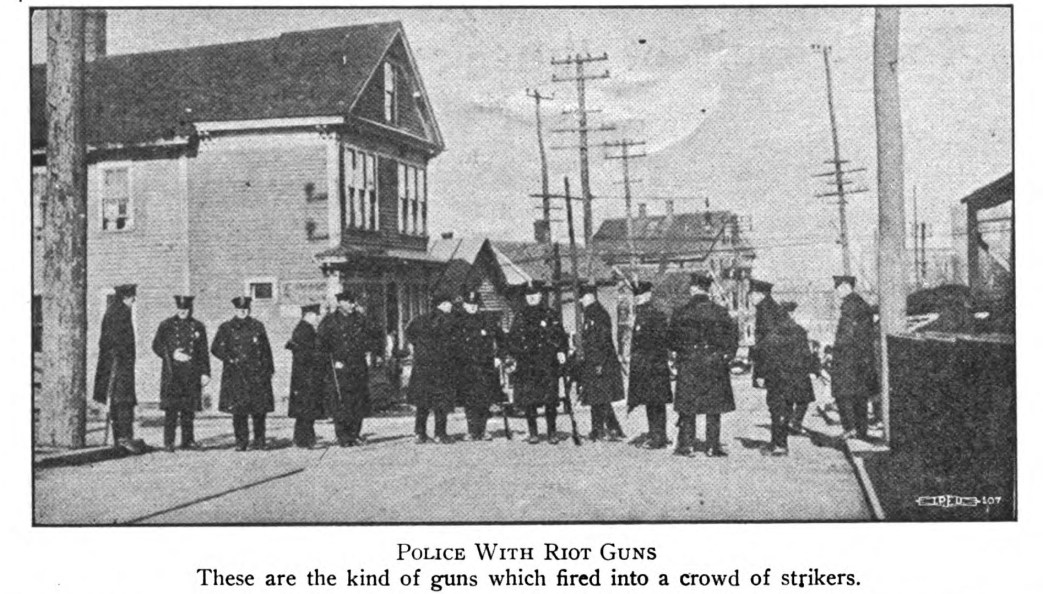

The mill-owners, swollen with their fat war-profits, and filled with rage at the rebellion of their hitherto so meek employees, fought the strike with great bitterness. With their enormous wealth they control the State institutions, and quickly the militia was thrown into the strike areas with instructions to shoot to kill. Private armies were also recruited, and the mills became small fortresses, with machine guns on roofs, and thugs and gunmen at every turn. Police were armed with shotguns. All this array of millions and of guns was pitted against the soup-kitchens and solidarity of the striking cotton workers. The guns killed several of the strikers, but solidarity kept the mills closed.

The employers sullenly refused all offers of arbitration, and all attempts at mediation, preferring to fight the battle out to a conclusion on the basis of naked power.

The cotton workers were totally unprepared for the bitter struggle that broke over their heads. They had neither organization nor understanding of how to conduct themselves in a battle against the employers. They suffered from the same demoralization that prevails throughout the entire textile industry. This demoralization is due chiefly to the epidemic of dual unionism to which the textile industry had been subject for many years past. I call it dual unionism, but “multiple unionism” would probably be a better name, for there has been a regular shoal of independent and disconnected unions in the industry. It seems as though every time a new revolutionary sect develops, or a new theory of unionism is worked out, its proponents come to the textile industry and set up a new labor movement there. The consequence is that the mass of the workers are so confused and demoralized by the conflicting claims of the various organizations that they don’t know which way to turn, and so they remain unorganized and helpless.

The extent to which dualism has afflicted textile industry unionism may be judged from the following list of organizations, each of which either has now, or has had recently, important influence in the industry. In addition to the United Textile Workers of America, which is the original organization, there are the Amalgamated Textile Workers of America, One Big Union, Industrial Workers of the World, Workers’ International Industrial Union, besides nine or ten independent craft unions, several split-offs from the above unions, and innumerable rumors of more splits and more organizations that may lead to further splits. Unless this dividing up tendency is stopped I prophecy that it will not be long until there is a separate union for each worker in the industry.

This condition in the organizational field among the textile workers is a very real condition. I can name 15 organizations that now exist in this field, and there are certainly others which I do not know of. The list makes an imposing show, and occupies a lot of space to write it down, but it certainly does not reflect strength and power on the part of the textile workers. What could demonstrate weakness and lack of organization more than a list like this, each name standing for a separate union now acting more or less in the textile industry?

United Textile Workers,

Amalgamated Textile Workers,

Industrial Workers of the World,

One Big Union,

American Federation of Textile Operatives,

National Loom Fixers Association,

Amalgamated Lace Operatives,

American Federation of Full Fashioned Hosiery Workers,

Brussels Body Weavers,

Mechanical Workers Union,

Tapestry Carpet Workers Union,

Associated Silk Workers,

Workers’ International Industrial Union,

International Spinners Union,

Amalgamated Knit Goods Workers.

A typical case of splitting the splits occurred in Lawrence at the end of 1920. Following the big strike, which had taken place recently, the Amalgamated Textile Workers, itself organized as a rival to the United Textile Workers, was in control of the bulk of the workers in the Lawrence mills. But this did not suit the chronic dualists, advocates of union perfectionism. They soon found cause to disrupt the organization. It seems that the Amalgamated officials did not part their hair exactly right, or that they were delinquent in certain fine points of industrial union doctrine, so the dualist enthusiasts, led by Ben Legere, recognized that there was nothing left for them to do but to destroy the predominant organization and start a new one. Therefore they launched a branch of the Canadian One Big Union. Later this split-off split again into two sections. The final and natural outcome of such confusion and secessionism was the practical destruction of the Amalgamated Textile Workers in Lawrence and the disappearance of unionism generally among the local textile slaves.

The great cotton strike, which at present writing is still on, emphasizes again the need for unity among the textile workers. Until such unity is achieved they will be helpless under the heel of their ruthless masters, notwithstanding possible local victories now and again. The necessary unity can never, be accomplished so long as the old policy is followed of launching new organizations that are supposedly based upon more accurate ideas and scientific plans that the others already in the field. There must be a return to first principles. Efforts must be made to start a movement among all the various factions of the textile workers, that will culminate in joining them together into one mass organization. We have had more than enough of splits. The process must be reversed. must join the unions together, instead of dividing them up. This will have to be the work of the Trade Union Educational League. No other organization in the country can or will undertake the job.

In the meantime, all possible financial assistance should be given to the starving strikers. All donations should be sent to the American Federation of Labor, or to Russel Palmer, General Secretary of the Amalgamated Textile Workers, 7 East 15th St., New York City.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v1n02-apr-1922.pdf