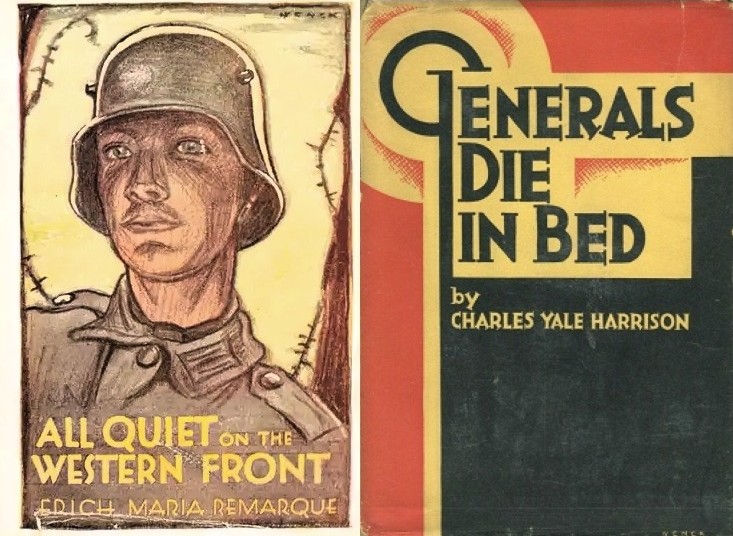

The novelist Charles Yale Harrison, a veteran of the Western Front wounded at the Battle of Amiens, whose 1930 book Generals Die in Bed was also a bestseller, reviews All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque

‘Here is War!’ by Charles Yale Harrison from New Masses. Vol. 5 No. 3. August, 1929.

This book is written out of the agony and torture which is war. To me, who stood in the trenches facing the author’s compatriots, the book seemed, as I read it, something more than a mere piece of war literature—it was war itself. The trench rats, the screaming and hissing of the shells, the fearladen eyes of the wounded as their comrades trample them to death in the delirious rush of the attack—these are all here and told with powerful simplicity and directness.

The hero of the story, the “I”, is an educated, sensitive youth of eighteen who finds himself at the front. We follow a company of German soldiers in battle, on rest, doing fatigue duty, under fire, on leave and finally in the autumn of 1918 the hero is back in the line anxiously waiting for the armistice.

The descriptions of troops under fire are among the best I have ever read. Not only are they convincing to the reader who has never heard the maniacal shriek of an oncoming H.E. shell, but to war veterans who have read the book, these passages are slices of reality itself. Listen to this:

“That moment it breaks out behind us, swells, roars and thunders. We duck down—a cloud of flames shoots up a hundred yards ahead of us.

“The next minute under a second explosion part of the woods rises slowly in the air, three or four trees sail up and then crash to pieces. The shells begin to hiss like safety-valves—heavy fire—.

“Take cover!’ yells somebody—‘Cover!’”

“Not a moment too soon. The dark goes mad. It heaves and raves. Darknesses blacker than the night rush on us with giant strides, over us and away…

“The wood vanishes, it is pounded, crushed, torn to pieces…”

***

After a year in the line the company of a hundred and fifty is all but wiped out. Only thirty-two men remain. The hero is blasted and shattered emotionally by his experiences at the front. He goes on leave.

The ten days pass all too soon.

Back at the front! The war is coming to an end. The German lines are being smashed by an overwhelming storm of allied artillery fire. For every German airman there are five English, French and Americans. How well I remember those days, endless marching, feet as raw hunks of beef, attack after attack. Tanks, heavy guns, supply lorries streaming in an endless metallic river towards the cracking German lines. The Hindenburg Line caves in, crumbles to pieces. The armistice is coming. The end.

The book has had an amazing success. It has been translated into ten languages within four months of its publication, Here in America at the time of writing it has sold 170,000 copies.

Critics of all countries have been unstinting in their praise. Time and again it has been called the finest war book ever written. The Manchester Guardian hailed it as “the greatest of all war books.” Ernest Toller wrote: “It is the strongest document that has come out of the war.” The zenith of American eulogy was reached when Christopher Morley wrote in the Saturday Review of Literature: “I regard any mature reader who has a chance to read this book and does not, and who, having read it, does not pass it on among a dozen others, as a traitor to humanity.”

It is a precarious business, I know, to stand as a non-conformist in the face of such a sweep of wild praise, but if the truth must be told All Quiet on the Western Front is not the best book on the war. A true war book written today while the world totters on the brink of another international catastrophe, must have in it a biting, accusing note. This, Remarque’s book does not have. There is very little in the book that will keep a jingo-inflamed youngster from throwing himself into the cauldron of another world war.

Bruno Frank, writing in Das Tage Buch, says of the book: “It is unanswerable, it cannot be evaded. It does not declaim, it never accuses, it only represents…”

Frank is perfectly correct. Remarque never accuses. For nearly 300 pages I read of every horror of war vividly painted; his mates are annihilated in a cause which Remarque surely knows to be senseless, wanton, criminal. He sees the people of Europe degraded, starved, humiliated, crushed. He sees his own mother and sister ill-fed, he sees other mothers and sisters in northern France, as I have seen, shamed, prostituted. He sees fifteen year-old, fair, Saxon boys stuffed into grotesque uniforms and sent off to the charnel-house of the Western Front. He has felt (although he does not even mention it in his book) the calculated, heartless oppression of the German military “discipline” and out of all this suffering not a word of condemnation, not a breath of accusation.

The hero of Remarque’s book is a thoughtful person. Between battles he thinks of the horror of war, of its wanton destructiveness, of how men are spiritually murdered; but never a word of accusation of the Krupps and the other munition manufacturers, the financiers, the Junkers who plunged the German nation into this howling nightmare. I looked in vain for a description of an officer shot by his men in battle. This was a fact, I know it, I saw it with my own eyes at the third battle of the Somme, Dos Passos knows it, Barbusse knows it and millions of soldiers who have lived to tell the tale know it—but Remarque has one of his characters say that all this talk about killing officers is “rot.”

When the author is through describing war, and he must of necessity draw conclusions, he indulges in vague metaphysics, in confused hopelessness. As the book rushes to its close I hoped to find at least one word of warning to the youth of the world of the impending military calamity which hangs over civilization (the book was written in 1928). Instead I found this:

“Had we returned home in 1916, out of the suffering and the strength of our experiences we might have unleashed a storm. Now if we go back we will be weary, broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope. We will not be able to find our way any more.

“And men will not understand us—for the generation that grew up before us, though it passed these years with us here, already had a home and a calling; now will return to its old occupation, and the war will be forgotten—and the generation that has grown up after us will be strange and will push us aside. We will be superfluous even to ourselves, we will grow older, a few will adapt themselves, some others will merely submit, and most will be bewildered;—the years will pass and in the end we shall fall into ruin.”

This is the message which Remarque gives to the millions of German youths who today are being befuddled with nonsense about war guilt, nationalism, who are being cajoled into the ranks of the monarchist Steel Helmets. With the whole of Europe staggering under a burden of armament that dwarfs that of 1914, he sadly concludes his book with aimless stuff about rootless, “lost” generations.

The older generation which fought with us, he says, will forget this war, this calculated sacrifice, will forget the crazed ferocity of a barrage, the ripped-open bellies, the spattered brains on parapets—it will forget this—why?–because it “already had a home and a calling; now it will return to its old occupations, and the war will be forgotten…” If one had an occupation and a home all was forgotten! What nonsense. Those of us who have lived through the war will never forget it; the memory of it persists like some fearful dream. This is vapid confusion, it is muddle-headedness; it is the sort of stuff which the arrant militarist likes to see written about war. It is faint sad stuff which cannot bear the bitterness of reality.

As Remarque stands in his trench and thinks these misty defeatist thoughts, what is happening behind the lines? The army is breaking into revolt. The republic is being established. In the streets of Berlin the barricades are lined by men no older than Remarque. Ground down by a murderous, unparralleled discipline the German soldier is breaking loose, is deserting, is shooting down his officers. In the streets of the German cities who is fighting the Junkers? The youth of Germany—the “rootless” ones, the “lost” generation!

* * *

All Quiet on the Western Front is not an anti-war book, it is simply a strong picture of certain phases of life in the German trenches. A mere recital of war-horror will never stop war. Ever since men first went into battle the terrors of human slaughter have been known. In London after an air-raid I saw recruiting offices beseiged by clamoring volunteers.

Books depicting war in all its nakedness have been written before 1914—Victor Hugo, Zola, Tolstoy, Stephen Crane, Ambrose Bierce—and in spite of these, when the drums of propaganda and war frenzy began to beat men went to war heedless of the horrors which awaited them. Better to tell the youth of the world why wars are made, not only how they are fought. Better to tell them of international competition for oil, coal, bonds, markets!

On page 283, Remarque speaks of the days of late summer, 1918. The German army is cracking under the strain of the re-enforced allied armies. The line is breaking in Belgium, France. Fresh armies are in the field; the air is black with allied planes. He writes:

“We are not beaten, for as soldiers we are better and more experienced we are simply crushed and driven back by overwhelming forces.”

Of course,—that’s how battles are won. The god of war marches with the strongest battalions. The same was true when the German army crashed through Belgium, when Maekensen went through Roumania—they advanced because they had superior numbers.

Every swashbuckling German staff officer has been saying this since 1918—We are not beaten…Every German reactionary nationalist has used this argument to whip up a militaristic feeling in Germany, to rehabilitate the old goose-stepping Imperial Army. There is nothing in Remarque’s book to offend the most devout monarchist who daily prays for the return of the Kaiser. Even Walter von Molo, president of the German Academy of Letters and ardent follower of Hindenburg writes of the book: “Let this book go into every home…for these are the words of the dead, the testament of all the fallen.”

Many critics of the book have said that this is the best book on the war. “Best” is a word that should be used on book jackets only. There are no best books; every sincere writer writes out of his suffering and agony and from the viewpoint of what he has felt and experienced. While Remarque’s book is a fine piece of realism, I still remember Barbusse’s Under Fire, E. E. Cummings’s The Enormous Room, and our own John Dos Passos’s Three Soldiers. Dos Passos’s book is still fresh in my memory because of its sharp note of condemnation; he saw war and did not shrink from accusing and condemning. How can one write of war and do otherwise?

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v05n03-aug-1929-New-Masses.pdf