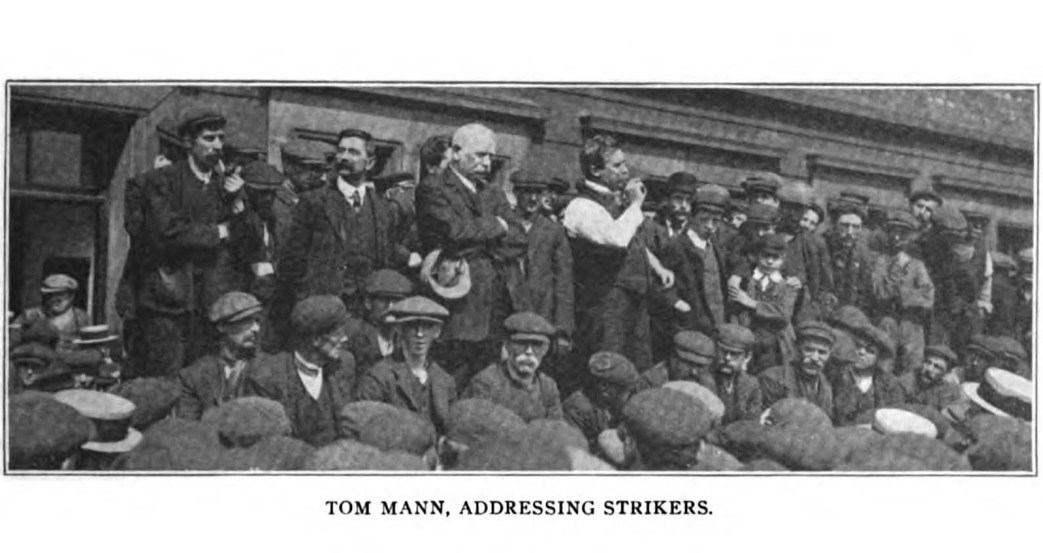

The years before the First World War saw waves of intense class struggle in Britain. One of the sharpest fights was the 1911 Liverpool general transport strike led by Tom Mann. He tells the story below.

‘The Transport Workers Strike in England’ by Tom Mann from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 6. December, 1911.

TO understand what led to the strike of transport workers in England it is necessary to bear in mind that a year ago there was formed in this country a “Transport Workers’ Federation.” This brought together most of the unions engaged in the carrying trades; and machinery was prepared to make common action easier than in former times. Also, Mr. J. Havelock Wilson, president of the Seamen’s Union for fully a year, had been doing his utmost in various countries to make common action possible at least among sailors and firemen, and he aimed at general action in the shipping industry.

After many conferences in continental countries, as well as Britain, it was ultimately decided that June of this year would be the best month for action. Not that Mr. Wilson or any other advocate of labor’s cause was really wishful for a strike; he and they desired to secure some solid advantages for the seafaring population, particularly, and for all connected therewith generally. And many scores of letters were written and sent to representative shipowners, to the Shipping Federation and to the British Board of Trade, to try and obtain reasonable consideration of the demands formulated by the unions, but without success.

This utterly failing, the shipowners and the public were informed that there was no alternative left to the men but that of withholding their labor, and that this would be done unless the shipowners would agree to a conference. Then, as the shipowners remained obdurate, it became necessary to fix upon the date when the strike should take place, and the middle of June was fixed upon, but it was decided not to inform the shipowners of the date.

Accordingly the date was kept a secret to those who were specially responsible, but the 14th of June the strike was declared in all British ports.

The shipowners were thus confronted with a state of affairs they were utterly unable to cope with. Mr. Lains, the chief official and adviser of the Shipping Federation, had systematically kept up the attitude of the unyielding plutocrat; on behalf of his colleagues, he had repeatedly declared that they were fully prepared to deal with any attempt that might be made to strike. He informed all that only an insignificant minority of the seafaring men were in any union and that the result of an attempt to strike would be, that other men would immediately be put in the places of the strikers, and that work would proceed without interruption.

The shipowners’ papers scathingly denounced Mr. Wilson and criticised the union maliciously and mercilessly. In spite of all this, in less than a week after the strike, the shipowners were most willing to meet in conference, and urged a settlement as speedily as possible. They readily conceded monetary advances of from ten to twenty shillings a month; they agreed to wipe out the objectionable methods that had been in vogue so long in respect to the medical examination ; they agreed to recognize the unions and approved the claim of union delegates to be present at “paying off” time and at “signing on.” Thus the changed attitude was almost unbelievable; what eighteen months of pleading with them had failed to do, a few days’ withholding of labor did.

It should be explained that only two of the unions in England decided definitely to declare war. These were the National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union and the Union of Cooks, Stewards, Ships’ Butchers and Bakers. Other unions had decided to sympathetically stand by and watch events.

The trade of the country was exceptionally brisk, and the coronation festivities were right in front and visitors from America, Europe and Australasia were arriving by ‘every passenger boat; any dislocation at such a time would naturally make itself felt in exceptional degree. And so it was.

For myself, I was stationed at Liverpool, which afforded a field quite big enough for one’s efforts, and here, as elsewhere, the strike was declared in the name of the two unions mentioned—the Seamen and Stewards—on Wednesday, the 14th of June, and the first of the conferences with shipowners took place on the following Monday. Inside of a fortnight a settlement had been arrived at with most of the principal shipping firms. But some of them had hopes that the Shipping Federation would after all be able to carry them through, and they declined to settle. This necessitated the extension of the strike to the carters and dockers, so they were invited and later joined the strikers. This was a great factor in bringing in the other shipping firms. They met first as members of the Shipping Federation, only to agree that it was impossible to fight collectively with any show of success and that “each firm must do the best it can for itself.” Settlements were proceeding apace when a new development took place. Of the 32,000 dock laborers m Liverpool and district, only 8,000 were organized, and these were receiving from six to ten shillings a week more than the unorganized. So now all the non-union dockets left work, went to the respective branches of the union and joined and insisted right away upon union rates and conditions. This looked like jeopardizing the gains already obtained by the men of the unions who had come out first. We had been urging the necessity of solidarity among all workers, and particularly among all transport workers, and now it was coming.

It proved to be a very trying time, but the result was all these men joined the union, and union wages and conditions were obtained, but before we reached finality with these negotiations, some seven thousand railway employes, most of them unorganized, came out in Liverpool, and claimed that their cause should receive attention.

This was a very serious addition to the family, and the strike committee had to consider most carefully the question of taking up their cause, as we had actually settled on behalf of the sailors, firemen, stewards and other seafaring men, and were finalizing conditions for the 30,000 dockers, and to take up the railway men, not only meant jeopardizing these gains, but brought us into direct conflict with the railway companies employing 600,000 persons. More serious still, the railway men’s unions were tied down to inaction on most matters by the Conciliation Act of 1907, which fixed conditions for seven years, and these unions were not favorable to any strike on the railways, and officials were sent down to stop further striking and to repudiate responsibility.

As chairman of the strike committee, I frankly admit that some of us fully realized the arduous task in front of us if we declared to back the railway men who had struck. However, after full deliberation, the strike committee considered that the only possible course for them to take was to take up the railway men’s case with the utmost zeal. We knew they were shamefully low paid and subjected to extremely harsh conditions. They were transport workers, too, and had shrewd courage, and asked our help. This we decided to give, and to refuse to handle any goods that were destined to or from the railways.

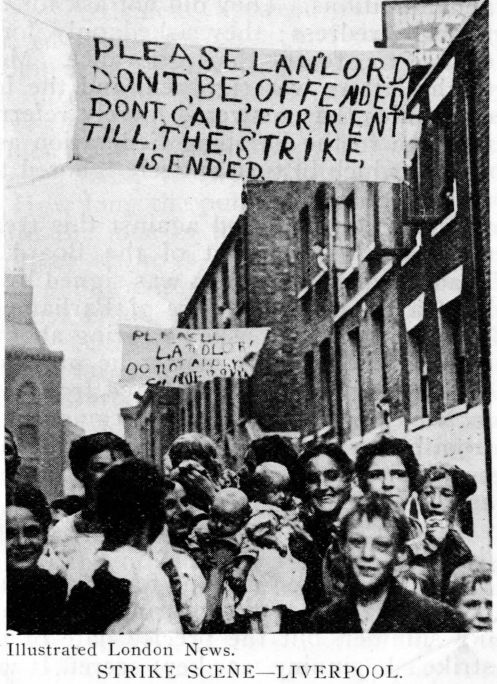

Up till this time all our activities had been characterized by the utmost courtesy on both sides. So far no collisions with the police had taken place, but on our refusing to handle railroad freight, the shipowners exhibited extreme annoyance, and after a few days declared that unless the men were prepared to work and handle all goods indiscriminately they, the shipowners, would declare a general lock-out on all deep sea trade.

They did so. This, it was expected, would kill the strike, instead of which the strike committee replied immediately. The lock-out commenced, by declaring a general strike on cross channel and coastal trade, and this was carried out.

It was during this period when the shipowners and capitalists generally saw that the strike was succeeding at all points, that they clamored for more police and military. There were now 80,000 men on strike and locked out in Liverpool alone, and to our great satisfaction the representatives of the three railway men’s unions, that had been attendant on the strike committee (when the strike committee decided to take up the railway men’s case), were themselves inspired by the boldness of such action. And knowing, as they did, that in most Lancashire towns the union railway men and nonunion men were holding mass meetings and declaring in favor of striking, the railway men’s officials themselves showed pluck and convened their respective executive councils in Liverpool. Again, to our agreeable surprise, these executives, collectively, unanimously agreed to support the strikers, and to insist upon redress. And so, for the first time in our history, the four principal unions of railway men in this country declared unanimously in favor of a fighting policy, and proceeded to act accordingly.

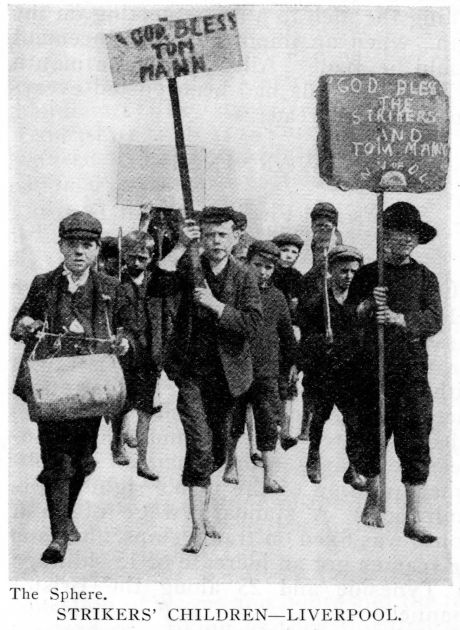

Of course, such an extensive strike as this soon meant serious shortage, as only by strike committee’s authorization could goods be obtained from the docks.

The first serious need was the milk supply. This being the staple food of children, authority was given for all facilities to be given to ensure full supply.

Next in importance was the bread supply, and facilities were given for bread and flour and such fuel as was necessary to make the food.

All supplies for hospitals and all other public institutions were ensured safe transit by the committee.

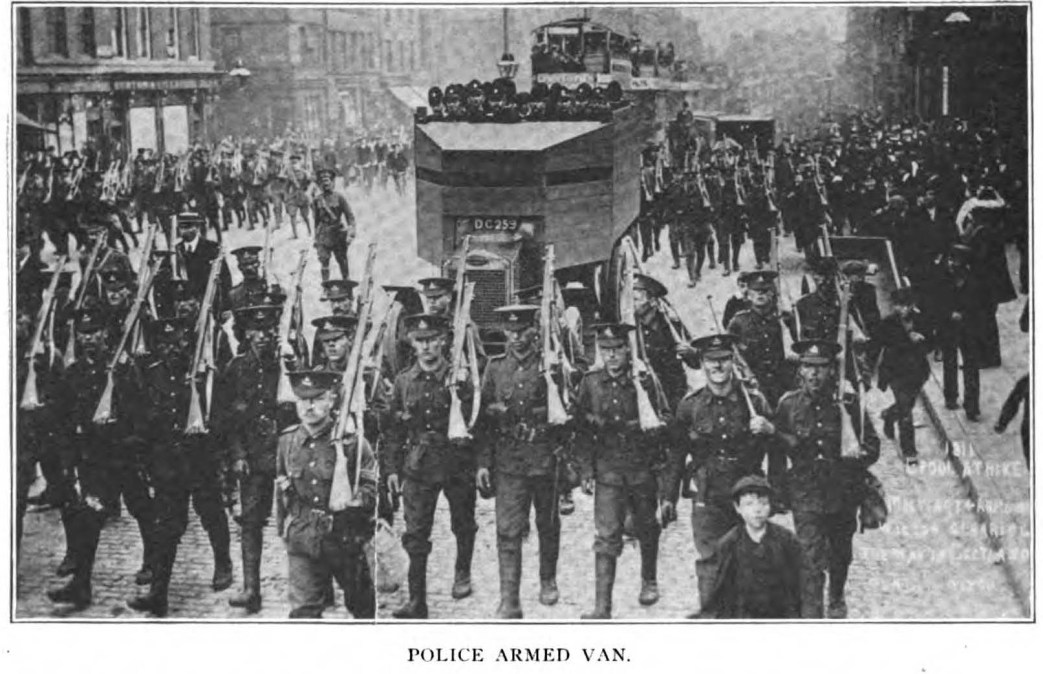

Seven to eight thousand military were in town, large numbers of police from outside districts, and thousands of special constables, but all these combined, including battleships in the Mersey, did not in any way frighten the workers, and the strike committee continued its duties with vigor, tact and success.

The pickets discharged their duties admirably; for the most part, they showed good judgment, alertness, pluck and resource, and the result was success at almost every point for the men on strike.

I will not attempt a description of the fights that took place between police and people, the chief of which was on Sunday, August 13th. The police were the aggressors, and the bludgeoning was brutal, but many a head inside a helmet had good reason to know there was a fight.

When the railway men’s executives agreed to take up the case of the men, they proceeded to London for negotiations and I believe they were staunch and true and sturdy and courageous. They insisted upon members of the executive meeting the railway magnates face to face, and not as heretofore with some governmental official as intermediary. But ere matters had proceeded far, the statesmen and politicians made themselves busy. Prime Minister Asquith showed true plutocratic interest and instinct, by declaring that if a general railway strike took place the government would place at the disposal of the companies military men in sufficient numbers to keep the railways going and they would be sent all over the country.

This did not cow the men nor prevent them declaring a strike; but among the railway men’s officials were Parliamentarians, and these succeeded in bringing in other Parliamentarians, and all these were for peace, and the non-extension of the strike.

To stop activity, to stultify it in the interests of capitalistic peace, is ever their object, and it was so here. In my judgment, had the executives themselves insisted upon conducting the negotiations themselves with the companies direct, and kept the fight going another two days, they would have achieved vastly more than they did. Still, minimize it as we may, it remains a solid fact that the railway men’s unions agreed unanimously for common action; that they did declare a national strike, and the response was most satisfactory; that they have obtained an assurance of redress of some of the grievances and it is highly probable that in a few weeks substantial increases of wages will be granted to certain grades, and the most objectionable features of the conciliation boards will be wiped out, or, if not, then I am quite sure the rank and file will demand action again to enforce these things.

Now the question is, what of the future? I conclude that the principles of syndicalism are here in the ascendancy, that the power and all around efficacy of direct action is being appreciated, and will be increasingly resorted to. It looks to the fighting proletarians here as though the capitalist state machine were not a suitable agency by means of which economic freedom should be won. We see the legislative institutions used to tie the people down. The ordinary workman is only just beginning to see this, but he is beginning to see it, and, in the same ratio, he sees that nationalization of services and commodities means the capitalization of these things; and now he is turning to industrial organization, not as formerly, to obtain a little better wage, etc., but beyond that, to actually obtain, first, control of industry, and ultimately ownership of the means of wealth production. This will be done through and by such industrial councils as will speedily grow out of the more perfected industrial organizations. So I say we shall achieve our freedom by the scientifically organized industrial union now growing very rapidly, the members of which are receiving an economic education, giving to them a courage born of knowledge, that will enable them to oppose and overcome all their enemies, be they institutions or privileged persons.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n06-dec-1911-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf