Franz Mehring brought all his considerable gifts to bear for his 1918 biography of Karl Marx from which this is a chapter.

‘The Young Hegelians’ (1918) by Franz Mehring from Karl Marx: The Story of His Life. Translated by Edward Fitzgerald. Covici Friede Publishers, New York. 1935.

From the spring of 1838, when he lost his father, Karl Marx spent three more years in Berlin, and the intellectual life in the circle of Young Hegelians opened up the secrets of the Hegelian philosophy to him.

At that time Hegelian philosophy was regarded as the Prussian State philosophy and the Minister of Culture Altenstein and his Privy Councillor Johannes Schulze had taken it under their special care. Hegel glorified the State as the reality of the moral idea, as the absolute reason and the absolute aim in itself, and therefore as the highest right as against the individual whose paramount duty it was to be a member of the State. This doctrine of the State was naturally very welcome to the Prussian bureaucracy, for it transfigured even the sins of the demagogue hunt.1

Hegel’s philosophy was not hypocritical and his political development explains why he regarded the monarchical form, embracing the best efforts of all the servants of the State, as the most ideal form of government. At most he considered it necessary that the dominant classes should enjoy a certain indirect share in the government, but even that share must be limited in a corporative fashion. He was no more prepared to consider a general representation of the people in the modern constitutional sense than was the Prussian King or his oracle Metternich.

However, the system which Hegel had worked out for himself was in irreconcilable antagonism to the dialectical method which he adopted as a philosopher. With the conception of being, the conception of non-being is given, and from the antagonism of the two the higher conception of becoming results. Everything is and is not at one and the same time, for everything is in a state of flux, in a state of permanent change, in permanent development and decline. Accordingly history is a process of development rising from the lower to the higher in an uninterrupted process of evolution. Hegel, with his universal knowledge in the most varied branches of historical science, set out to prove this, though only in that form which accorded with his own idealist conception of the absolute idea expressing itself in all historical happenings. This absolute idea Hegel declared to be the vitalizing spirit of the whole world without, however, giving any further information about it.

The alliance between the philosophy of Hegel and the State of the Frederick-Williams could therefore be no more than a marriage of convenience lasting as long as each partner was prepared to minister to the convenience of the other. This worked excellently in the days of the Carlsbad decisions and the demagogue hunt, but the July revolution of 1830 gave European development such a strong impetus that Hegel’s method was seen to be incomparably more reliable than his system. When the effects of the July Revolution, weak enough in any case as far as Germany was concerned, had been stifled and the peace of the graveyard had again descended on the land of thinkers and poets, Prussian Junkerdom hastened to dig out the old dilapidated lumber of mediaeval romanticism for use against modern philosophy. This was made easier by the fact that Hegel’s admiration was directed less to the cause of Junkerdom than to the cause of the tolerably enlightened bureaucracy, and by the fact that with all his glorification of the bureaucratic State Hegel had done nothing to maintain religion amongst the people, an endeavour which is the alpha and omega of all feudal traditions and, in the last resort, of all exploiting classes.

The first collision took place therefore on the religious field. Hegel declared that the biblical stories should be regarded in the same way as one would regard profane stories, for belief had nothing to do with the knowledge of common and real matters; and then along came David Strauss, a young Swabian, and took the master at his word in deadly earnest. He demanded that biblical history should be subjected to normal historical criticism and he carried out this demand in his Life of Jesus which appeared in 1835 and created a tremendous sensation. In this book Strauss picked up the threads of the bourgeois enlightenment movement of the eighteenth century of which Hegel had spoken all too contemptuously as “pseudo-enlightenment.” Strauss’ capacity for dialectical thought permitted him to go far more thoroughly into the question than old Reimarus had done before him. Strauss did not regard the Christian religion as a fraud or the apostles as a pack of rogues, but explained the mythical components of the gospel story from the unconscious creations of the early Christian communities. Much of the New Testament he regarded as a historical report concerning the life of Jesus, and Jesus himself as a historical personage, whilst he assumed a historical basis for all the more important incidents mentioned in the Bible.

Politically considered, Strauss was completely harmless and he remained so all his days. But the political note was sounded rather more sharply and clearly in the Hallische Jahrbücher2, which were founded in 1838 by Arnold Ruge and Theodor Echtermeyer as the organ of the Young Hegelians. This publication also dealt with literature and philosophy and at first it was intended to be no more than a counterblast to the Berliner Jahrbücher, the stick-in-the-mud organ of the Old Hegelians. Ruge, who had played a part in the “Burschenschaft” movement3, and suffered six years’ imprisonment in Köpenick and Kolberg as a victim of the Demagogue hunt, quickly took the lead in the partnership with Echtermeyer, who died young. Ruge had not taken his earlier fate tragically, and later on a fortunate marriage gave him a lectureship at the University of Halle. He led a comfortable life and, despite his earlier misfortunes, this permitted him to declare the Prussian State system free and just. Indeed he would have liked to justify in his person the malicious saying of the old Prussian mandarins that no one made a career for himself more quickly than a converted Demagogue, but this was just the trouble.

Ruge was not an independent thinker and still less a revolutionary spirit, but he had sufficient education, industry and fighting spirit to make a good editor of a learned magazine, and on one occasion he called himself, not without a certain amount of truth, a wholesale merchant of intellectual wares. Under his leadership the Hallische Jahrbücher developed into a rendezvous of all the unruly spirits, men who possess the advantage – unfortunate from the governmental point of view – of bringing more life into the press than anyone else. For instance, David Strauss as a contributor did more to hold the attention of readers than all the orthodox theologians, fighting tooth and nail for the infallibility of the Bible, put together could have done. Ruge, it is true, made a point of assuring the authorities that his publication propagated “Hegelian Christianity and Hegelian Prussia,” but the Minister of Culture Altenstein, who was already being hard pressed by the romanticist reaction, did not trust his assurances and refused to be moved by Ruge’s urgent pleadings for a State appointment as a recognition of his services. The result was that the Hallische Jahrbücher began to realize that something to be done to shiver the fetters which imprisoned Prussian freedom and justice.

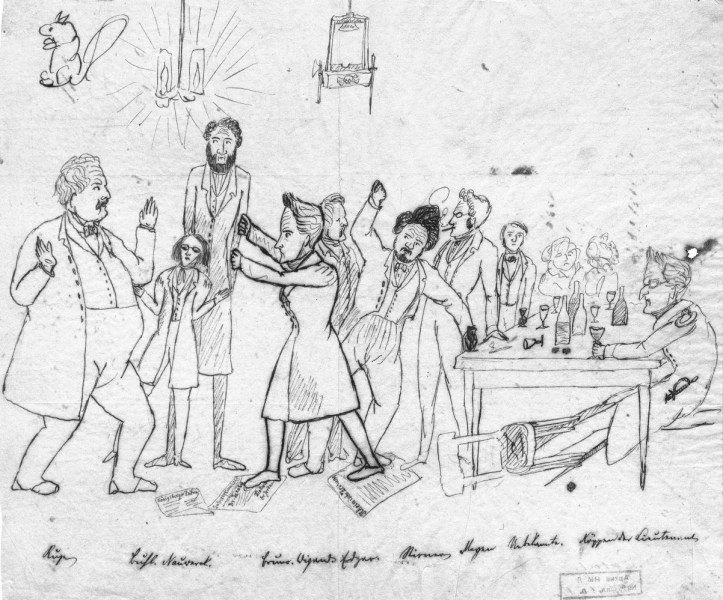

The Berlin Young Hegelians, in whose midst Karl Marx spent three years of his life, were almost all contributors to Ruge’s Hallische Jahrbücher. The club membership was composed chiefly of university lecturers, teachers and writers. Rutenberg, who is described in one of Marx’s earlier letters to his father as “the most intimate” of his Berlin friends, had been a teacher of geography to the Berlin Corps of Cadets, but had been dismissed, allegedly for having been found one morning drunk in the gutter, but in reality because he had come under suspicion of writing “malicious articles in Hamburg and Leipzig newspapers. Eduard Meyen was connected with a short-lived journal which published two of Marx’s poems, fortunately the only two that ever saw the light of day. Max Stirner was teaching at a girls’ school in Berlin, but it has not been possible to discover whether he was a member of the club at the same time as Marx and there is no evidence that the two ever knew each other personally. In any case, the matter is not of much interest because no intellectual connection existed between them. On the other hand, the two most prominent members of the club, Bruno Bauer, a lecturer at the University of Berlin, and Karl Friedrich Köppen, a teacher at the Dorotheen Municipal Secondary School for Modern Subjects, had a great influence on Marx.

Karl Marx was hardly twenty years old when he joined the club of Young Hegelians, but as so often happened in later years when he entered a new circle, he soon became its centre. Both Bauer and Köppen, who were about ten years older than Marx, soon recognized his superior intellect and asked for no better comrade than this youngster who was still in a position to learn much from them and did so. The impetuous polemic which Köppen published in 1840, on the centenary of the accession [6] of Frederick the Great of Prussia, was dedicated “To my Friend Karl Marx of Trier.”

Köppen possessed historical talent in very great measure and his contributions to the Hallische Jahrbücher still vouch for this fact. It is to Köppen we owe the first really historical treatment of the reign of terror during the Great French Revolution. He subjected the representatives of contemporary historical writing, Lee, Ranke, Raumer and Schlosser, to the liveliest and most trenchant criticism and himself made sallies into various fields of historical research, from a literary introduction to Nordic mythology which is worthy of a place beside the works of Jakob Grimm and Ludwig Uhland, to a long work on Buddha which earned even the recognition of Schopenhauer who was otherwise not well disposed towards the old Hegelian. The fact that a man like Köppen yearned for “the spiritual resurrection” of the worst despot in Prussian history in order “to exterminate with fire and sword all those who deny us entrance into the land of promise” is sufficient to give us some idea of the peculiar environment in which these Berlin Young Hegelians lived.

However, two factors must certainly not be overlooked: First of all the romanticist reaction and everything connected with it did its utmost to blacken the memory of “Old Fritz.” Köppen himself described these efforts as “a horrible caterwauling: Old and New Testament trumpets, moral Jew’s harps, edifying and historical bagpipes, and other horrible instruments, and in the middle of it all hymns of freedom boomed out in a Teutonic beer bass.” And secondly, there had as yet been no critical and scientific examination which came anywhere near doing justice to the life and actions of the Prussian King, nor could there have been any such examination because the conclusive sources necessary for such a work had not yet been opened up. Frederick the Great enjoyed a reputation for “enlightenment” and that was sufficient to make him hated by the one and admired by the other.

Köppen’s book also aimed at picking up the threads of the eighteenth century bourgeois-enlightenment movement, and in fact, Ruge once declared of Bauer, Köppen and Marx that their chief joint characteristic was that they all proceeded from this movement; they represented a philosophic Jacobin Party and wrote a Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin on the storm-swept horizon of Germany. Köppen refuted the “superficial declamations” against the philosophy of the eighteenth century. Despite their tediousness, we owe much to the German pioneers of bourgeois enlightenment. Their one deficiency had been that they were not enlightened enough. Here Köppen was tilting chiefly at the thoughtless imitators of Hegel, “the lonely penitents of the idea,” “the old Brahmins of logic,” sitting with crossed legs, eternally and monotonously gabbling the Three Holy Vedas again and again, pausing only now and then to throw a lustful glance into the world of the dancing Bayaderes.

The shaft went home, for Varnhagen promptly condemned the book in the organ of the Old Hegelians as “disgusting” and “repulsive,” probably feeling himself particularly wounded by the plain speaking of Köppen about “the toads of the marsh,” that vermin without religion, without a Fatherland, without convictions, without conscience, without heart, feeling neither cold nor heat, nor joy nor sorrow, nor love nor hatred, without God and without the devil, miserable creatures who squatted around the gates of hell and were too vile to be granted admittance.

Köppen honoured “the great King” only as “a great philosopher, but he went further in his advocacy than was permissible even according to the standards of Frederician knowledge then prevailing. “Unlike Kant,” he declared, “Frederick the Great did not subscribe to two forms of reason: a theoretical one bringing forward its doubts, objections and negations fairly honestly and audaciously, and a practical one, under guardianship and in the public pay, to make good what the other did ill and to whitewash its student pranks. Only the most elementary immaturity can contend that as compared with the royal and practical reasoning his philosophical theoretical reasoning appears particularly transcendental, and that often Old Fritz dismissed the hermit of Sans Souci from his mind. On the contrary, the King never lagged behind the philosopher.”

Anyone who dared to repeat Köppen’s contentions to-day would certainly lay himself open to the reproach of most elementary immaturity even from the Prussian historical school; and even for the year 1840 it was going rather too far to place the lifelong enlightenment work of a philosopher like Kant in the same category as the pseudo-enlightenment farce played by the Borussian despot on the French brilliants who were content to act as his court jesters.

Köppen suffered under the peculiar poverty and emptiness of Berlin life which was fatal to all the Young Hegelians living there, and although he should have been able to guard himself against it more easily than the others, it affected him still more than it did them. It expressed itself even in a polemic which had undoubtedly been written with all his heart. Berlin lacked the powerful backbone which industry in the Rhineland, already highly-developed, gave to bourgeois consciousness there. The result was that when the questions of the day took on a practical form the Prussian capital dropped behind Cologne, and even behind Leipzig and Königsberg. Writing of the Berliners of the day the East Prussian Walesrode declared: “They think themselves tremendously free and daring when they make fun of Cerf and Hagen, of the King and the events of the day, sitting safely in their cafe and joking in their familiar street-rowdy style.” Berlin was in fact nothing more than a military garrison and residence town, and the petty-bourgeois populace compensated itself with malicious and paltry back-biting for the cowardly subservience it showed to every court equipage. A regular rendezvous for this sort of opposition was the gossip salon maintained by Varnhagen, the same man who crossed himself in pious horror even at the idea of Frederician enlightenment as Köppen understood it.

There is no reason to doubt that the young Marx shared the opinions expressed in the book which brought his name before the general public for the first time. He was closely acquainted with Köppen and adopted the latter’s style to a considerable extent. Although their paths soon branched off in different directions, the two always remained good friends and when Marx returned to Berlin twenty years later on a visit he found Köppen “just the same as ever” and they celebrated a joyful reunion and spent many happy hours in each other’s company. Not very long afterwards, in 1863, Köppen died.

NOTES

1. “Demagogue” was the name given to the Radicals and Liberals of the Metternich era on the continent, and as all forms of democratic agitation were prohibited by the Karlsbad Decisions in 1819 the Demagogues were outlaws. The “Demagogue Hunt” Was the name given to the fierce campaign of persecution conducted against them. – Tr.

2. Hallische Jahrbücher: Halle Annuals. The custom, widely prevalent in Germany at the time, of issuing so-called “Annuals,” which were in fact collections of articles, was due to a desire to circumvent the censorship which, although it applied strictly to shorter publications, excepted those of more than 20 “Bogen” or 320 pages. – Tr.

3. The “Burschenschaft” movement was founded in Jena in 1815 as a bourgeois-democratic students’ organization opposed to the traditional aristocratic students’ “Corps.” It was imbued with a libertarian and militant spirit and in consequence it was suppressed by the decisions of the Karlsbad Congress in 1819. The “Burschenschaften” still exist, but their original significance has naturally long ago been lost. – Tr.

PDF of 1935 book: https://archive.org/download/karlmarxstorylife/karlmarxstorylife.pdf