Simultaneous with the strike Communist-led textile strike in Gastonia, North Carolina was the United Textile Workers strike against the mills of Elizabethton, Tennessee. Mary Heaton Vorse with a powerful vignette from the sell-out at Elizabethton.

‘Elizabethton Sits on a Powder Keg’ by Mary Heaton Vorse from New Masses. Vol. 5 No. 2. July, 1929.

In Elizabethton there is a vast wooden shed called the Tabernacle. Originally it was built for Happy Valley’s great revival meetings.

May 25th it was filled with the striking rayon workers. They had been suddenly summoned to hear “peace” terms gotten by U.S. Mediator, Anna Weinstock and a committee of five workers. These workers had not been elected democratically. They had been chosen by the U.T.W. organizers. The news that strike settlement was under way came to the rank and file of the strikers as unexpectedly as a stroke of lightening.

Anna Weinstock, the only woman Mediator in the Department of Labor, read aloud the terms offered by the Bemberg-Glanzstoff Corporation. She read with all the elation of a personal victory!

1. All employes shall register immediately.

2. If an employe is not reinstated definite reasons shall be given such an employe, and if he feels he is being discriminated against he may refer his case to an impartial person for a hearing and decision. The impartial person to sit in such cases shall be E.T. Willson. (Willson is the company’s employment and personnel manager whose appointment was announced shortly before the meeting was called to vote on the terms.)

3. The management will not discriminate against an employe because of membership in any organization, nor because of legitimate and lawful activities in such organization as long as they are carried on outside the plants.

4. For the purpose of adjusting grievances which may arise, the management will meet a committee of its employes.

While she read, the great auditorium was filled with murmurs and restless shifting of the 2,000 strikers. She finished. There was amazed silence. Then a great shout of “No!”

Boos came from the packed platform and “Boos” were reechoed back from the crowd on the floor. The will of the workers had spoken, loudly and spontaneously. Their refusal was emphasized by anger.

Discrimination. That is written all through the settlement. Dr. Arthur Mothwurf, President of the corporation, has stated in today’s papers who he will take back. He has made it clear enough. “We must decline to employ persons of undesirable character.”

The workers had not struck for such an agreement. The majority of the strikers were sure that once the strike was won, they would have better working conditions, wages and hours. Strikers would say to you, “We’ll have the eight hour day when we win the strike” or “They’ll recognize the Union before we’ll quit.”

The strikers and the leaders confronted each other. There was amazement on both sides. Amazement at the terms, amazement on the part of the U.T.W. officials that the strikers filled the air with boos of derision.

The great company of strikers were like a person with one will. They were like a swift runner who has been checked with the goal in sight. Victory was what they wanted—not compromise.

For nearly three hours the A.F. of L. officials talked to the strikers; they entreated, they pleaded with them. They dazed the strikers with words, confused them and deadened them with speech and argument. Throughout the talking, whenever the settlement was re-read, “Boos!” came from the strikers.

Had a single voice told them to resist the settlement terms the strikers would have arisen in jubilation. They had only begun to fight.

A standing vote was asked for. They voted for the settlement. Silent and angry, they filed out. No applause of victory, no happy buzz of congratulation. One tall boy shouted:

“They broke the strike!”

Afterwards they swarmed around the streets like clusters of angry bees. You should hear them saying: “It’s a sell-out!”

Bowles’ rooming house is strike headquarters. This was where Mack Elliot stayed. He is a machinist and very high paid for Elizabethton. He had just built a new bungalow. The strikers used to meet there. Then his house was dynamited. There is nothing left of it now but kindling.

Other active strikers and sympathizers live here too. Every night two boys guard in front and in back to see that the place won’t be dynamited or that no one will be kidnapped. Though the strike has been “settled,” the state troops are still in town and the boys are still guarding headquarters. Everybody is restless. There is a great deal of coming and going.

About midnight, one after another, there are six detonations of dynamite. There has hardly been a night where there has not been shooting, dynamite explosions or fire. We have gotten used to them. Tonight we are on edge, and we appear, each one at our doors, like people in a farce.

White, one of the strike leaders, with several of the strikers, comes out of a room where he has been discussing the settlement. Mr. and Mrs. Bowles are there. The guards join us. We bring up chairs and all sit down and talk around the cold cast iron stove.

White begins. “I don’t like this settlement. I don’t like it at all. They ain’t pinned down any. It’s just like the other settlement—going to be discrimination, I say.”

Bowles declares: “There’s holes in that agreement.”

“Holes! There’s holes as big as yore garage door—holes big enough to drive a hearse through.”

“We’ll all be out again soon enough,” the youngsters say. The youngsters don’t care—strikes are fun.

The older people express their sense of betrayal and of disillusion. They were conscious that the strikers were marching along on a high tide of victory. The settlement has come and it is destined to amputate the local leadership from the body of the strikers. The leaders will be sent into backwaters of inaction. The will and brains, the eyes and head, of the Union will be chopped off.

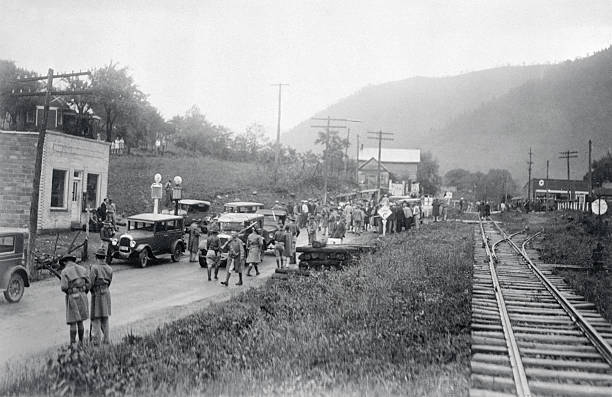

Monday morning the office registration opens. From dawn on, a milling crowd surrounded it. Strikers come from the hills and from distances as far as 20 miles. It was a crowd filled with foreboding. “Sell-out” was on everybody’s lips. They began to stream back to headquarters. By 9 o’clock the Tabernacle was filled with excited people. People had come from the hills who had had no part in the voting.

There is a sense of riot in the air. People spring up from their seats to speak. None of their leaders are there, all except John Edelmann. They are all over in Johnson City in the John Sevier Hotel.

Word went around—“The Communists have come.” William Kelly and the other leaders are telephoned for in a hurry.

McGrady tells the press that the Communists have stirred up the trouble.

At last, the leaders begin to come. William Kelly, wiping his perspiring brow, whispers: “Beal’s in the audience!” The Citizen Committee, hysterically swear out a warrant for Weisbord.

Down in the audience, Fred Beal sits quietly. He and a woman organizer have driven from Gastonia with two Gastonia strikers. He asks permission to bring greetings from the textile workers of Gastonia to those of Elizabethton. He is denied the floor. What if he were to get up and denounce the settlement. What would happen then with this restless, dissatisfied crowd? That is what every one is thinking.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v05n02-jul-1929-New-Masses.pdf