A chapter on language from Kautsky’s larger work on materialism.

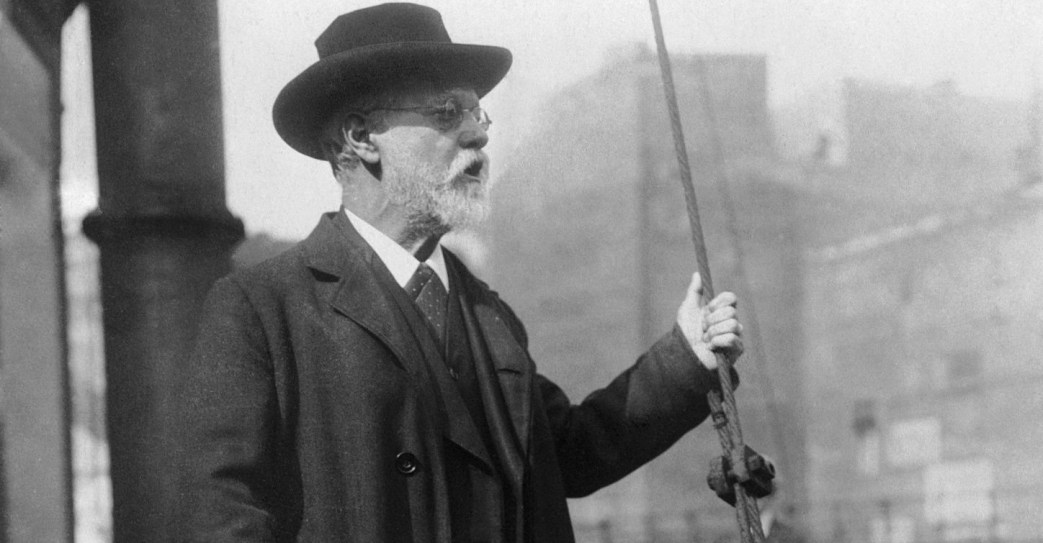

‘Language’ by Karl Kautsky from from Ethics and the Materialist Conception of History. Charles H. Kerr Publishers, Chicago. 1906.

Since human society in contrast to the animal is continually changing, for that very reason the people in it must be continually changing. The alteration in the conditions of life must react on the nature of the men, the division of labour necessarily develops some of his natural organs in a greater degree and transforms many. Thus for instance the development of the human ape from a tree fruit eater into a devourer of animals and plants, which are to be found on the ground, was bound to be connected with a transformation of the hind pair of hands into feet. On the other hand, since the discovery of the tool no animal has been subject to such manifold and rapid changes in his natural surroundings as man and no animal confronted with such by an ever growing problem of adaptation to his surroundings as he, and had to use its intellect to the same degree as he. Already at the beginning of that career which he opened with the discovery of the first tool, superior to the rest of the animals by reason of his adaptability and his intellectual powers, he was obliged in the course of his history to encourage both qualities in the highest degree.

If the changes in the society are able to transform the organism of man, his hands, his feet, his brain, how much the more and how much greater to change his consciousness, his views of that which was useful and harmful, good and bad, possible and impossible.

If man begins his rise over the animals with the discovery of the tool, he has no need to first create a social compact as was believed in the 18th century and as many theoretical jurists still believe in the 20th. He enters on his human development as a social animal with strong social impulses. The first ethical result of human society could only be to influence the force of these impulses. According to the character of society these impulses will be either strengthened or weakened. There is nothing more false than the idea that the social impulses are bound to be continually strengthened, as society develops.

At the beginning of human society that certainly will have been true. The impulses which in the animal world had already developed the social impulses, human society, permits to remain in full strength, it adds further to that – cooperation in work. This co-operation itself has made a new instrument of intercourse of social understanding necessary, language. The social animals could get through, with few means of mutual understanding, cries of persuasion, of joy, of fright, of alarm, of anger and sensational noises. Every individual is with them a whole, which can exist for itself alone. But sensational noises do not, however, suffice, if there is to be common labour or if different tasks are to be allotted, or different products divided. They do not suffice for individuals who are helpless without the help of other individuals. Division of labour is impossible without a language, which describes not merely sensations, but also things and processes, it can only to that degree develop in which language is perfected, and it for its part brings with it the need for it.

In language itself the description of activities and especially the human, is the most primitive; that of the things comes later. The verbs are older than the nouns, the former form the roots from which the latter are derived.

Thus declares Lazarus Geiger:

“When we ask ourselves why light and color were no nameable objects for the first stage of language while the act of painting of the colors was, the answer lies in this that man first only described his actions or those of his kind; he noticed only what happened to himself or in the immediate and to him directly interesting neighborhood, at a period when he had for such things as light and dark, shining objects and lightning no sense and no power of conception. If we take samples from the great number of concepts which we have already touched on (in the book) they go back in their beginning to an extremely limited circle of human movements. For this reason the conception of natural objects evolves in such a remarkably roundabout manner from that conception of a human activity, which in one way or other called attention to them and often brings something that is a distant approximation to them. So the tree is something stripped of its bark, the bark something ground, the corn which grows on it something without the husk. Thus earth and sea, nay even the idea cloud, and heaven itself, emerge from the same root concept of something ground up or painted, a sort of clay-like liquid.” (Der Ursprung der Sprache, pp.151-3.)

This way of the development of language is not surprising if we grasp the fact that the first duty of language was the mutual understanding of men in common activities and common movements. This role of language as a help in the process of production makes it clear why language had originally so few descriptions of color. Gladstone and others have concluded from that that the Homeric Greeks and other primitive peoples could only distinguish few colors. Nothing more fallacious than that. Experiments have shown that barbarian peoples have a very highly developed sense of color. But their color technic is only little developed, the number of colors which they can produce is small, and hence the number of their descriptions of color is small.

“When man gets so far as to apply a color stuff, then the name of his color stuff easily takes on an adjectival character for him. In this way arise the first names of colors.” (Grant Allen, The Color Sense, p.254.)

Grant Allen points to the fact, that even today the names of colors increase as the color technic grows. The names of the colors serve first the purpose of technic and not the purpose of describing nature.

The development of language is not to be understood without the development of the method of production. From this latter it depends whether a language remains the dialect of a tiny tribe or a world language, which a hundred million men speak.

With the development of language an uncommonly strong means of social cohesion is won, an enormous strengthening and a clear consciousness of the social impulses. In addition it certainly produced quite other effects; it is the most effectual means of retaining acquired knowledge, of spreading this, and handing it on to later generations; it first makes it possible to form concepts, to think scientifically. Thus it starts the development of science and with that brings about the conquest of nature by Science. Now man acquires a mastery over Nature and also an apparent independence of her external influences, which arouse in him the idea of freedom. On this I may be allowed a private deviation. Schopenhauer very rightly says:

The animal has only visual presentations and consequently only motives which it can visualize. The dependence of its acts of will from the motives is thus clear. In men this is no less the case and they are impelled (always taking the individual character into account) by the motive with the strictest necessity: only these are not for the most part visual but abstract presentations, that is conceptions, thoughts which are nevertheless the result of previous views thus of impression from without. That gives him a certain freedom, in comparison namely with the animals. Because he is not like the animal determined by the visual surroundings present before him but by his thoughts drawn from previous experiences or transmitted to him through teaching. Hence the motive which necessarily moves him is not at once clear to the observer with the deed, but he carries it about with him in his head. That gives not only to his actions taken as a whole, but to all his movements an obviously different character from those of the animal; he is at the same time drawn by finer invisible ones. Thus all his movements bear the impress of being guided by principles and intentions, which gives them the appearance of independence and obviously distinguishes them from those of the animal. All these great distinctions depend however entirely from the capacity for abstract presentations, conceptions. (Preisschrift über die Grundlage der Moral, 1860, p.148.)

The capacity for abstract presentations depends again on language. Probably it was a deficiency in language which caused the first concept to be formed. In Nature there are only single things; language is, however, too poor to be able to describe every single thing. Man must consequently describe ail things which are similar to each other with the same word; he undertakes with that however, at the same time unconsciously a scientific work, the collection of the similar, the separation of the unlike. Language is then not simply an organ of mutual understanding of different men with each other but has become an organ of thinking. Even when we do not speak to others, but think to ourselves only the thoughts must be clothed in certain words.

Does, however, language give man a certain freedom in contrast to the animals, this, all the same, only develops on a higher plane what the formation of the brain had already begun.

In the lower animals the nerves of motion are directly connected with the nerves of sensation; here every external impression at once releases a movement. Gradually, however, a bundle of nerves develops into a centre of the whole nervous system, which receives all the impressions and is not obliged to transmit all to the motor nerves, but can store them up and work them off. The higher animal gathers experiences which it can utilize and impulses which even under certain circumstances it can hand on to its descendants.

Thus through the medium of the brain the connection between the external impression and the movement is obscured. Through language, which renders possible the communication of ideas to others, as well as abstract conceptions, scientific knowledge, and convictions, the connection between sensation and movement becomes in many cases completely unrecognizable.

Something very similar happens in economics. The most primitive form of the circulation of wares is that of barter of commodities: of products which serve for personal or productive consumption. Here from both sides an article of consumption is given and received. The object of the exchange, that is consumption, is clear.

That alters with the rise of an element to facilitate circulation, money. Now it is easy to sell without at once buying, just as the brain makes it possible that impressions should work on the organism without at once releasing a movement. And as this renders possible a storing up of experiences and impulses, which can even be transmitted to descendants, so can notoriously from gold a treasury be collected. And as the collection of that treasury of experiences and impulses under the necessary social conditions finally renders really possible the development of science and the conquest of nature by science, so does the collection of every treasure render possible when certain social conditions are also there the transformation of money into capital, which raises the productivity of human labor in the highest degree and completely revolutionizes the world within a few centuries to a greater degree than formerly occurred in hundreds of thousands of years.

And so just as there are Philosophers who believe that the elements, Brain and Language, intellectual powers and ideas which form the connection between sensation and movement are not simple means to arrange this connection more conveniently for the individual and society, thus apparently to increase their strength, but that they are of themselves sprung from independent sources of power, nay, finally coming even from the creator of the world, – so there are economists who imagine that money brings about the circulation of goods and, as capital, renders it possible to develop human production enormously; that it is this that is the starter of this circulation, the creator of these forces, the producer of all values which are produced over and above the product of the primitive handwork.

The theory of the productivity of capital rests on a process of thought which is very similar to that of the freedom of the will and the conception of a moral law, independent of time and space, which regulates our actions in time and space.

Marx was just as logical when he contradicted the one process of thought as the other.

Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement. It remains a left wing publisher today.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/ethicsmaterialis00kaut/ethicsmaterialis00kaut.pdf