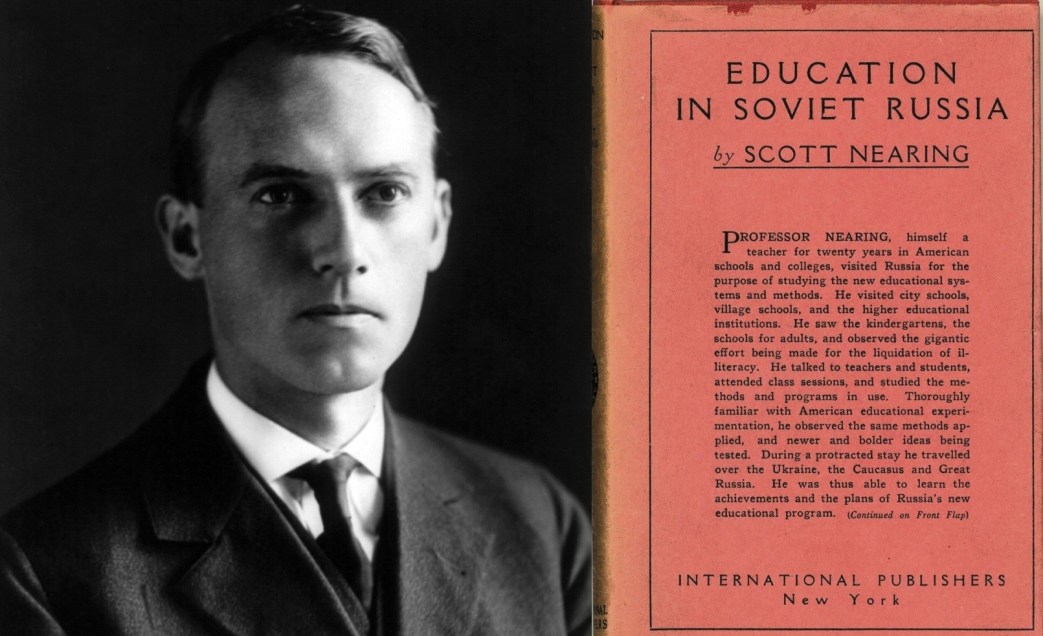

We begin the full transcription of Scott Nearing’s 1926 ‘Education in Soviet Russia’. An early project of International Publishers, and one of the first serious English-language studies, Nearing spent two months in 1925 researching schools in the Soviet Union. Nearing himself taught for decades and was a leader of the new, ‘progressive’ U.S. educators. Born to a bourgeois family, Nearing received his doctorate in economy from the Wharton School of Business and spent years teaching economy and sociology there and at Swarthmore College before his dismissal in 1915 for his political activity, particularly around child labor. Nearing grew increasingly radical during World War One. His old class viewing him as he was, their inveterate enemy, began a campaign against him leading to his indictment for sedition under the Espionage Act in 1918. Nearing did not bend. He became a Communist and offered his services, originating the Federated Press, a pro-worker news wire, and building workers education programs. Each of thirteen chapters to follow, and linked below.

‘Foreword’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

People outside of the Soviet Union have heard a great deal about Soviet politics and something about Soviet economics. They have had almost no information about Soviet education. This is a pity.

Nothing that is going on in the Soviet Union at the present moment is more important for the remainder of the world than the work in education. The most extensive educational experiments that can be found anywhere are now being made in the Soviet schools. Elsewhere there are a few centres of experimental education. Quite frequently these are located in expensive private schools to which only the children of the rich can go. In no case is there more than a small fraction of the educational work of any country on an experimental basis.

Soviet education is practically all experimental. The Revolution of 1917 tore the old social system up by the roots. The Civil War cleared away much of the debris. Since 1921 and 1922, therefore, the educational authorities of the Soviet Union have had a relatively free field in which to solve their educational problems in a way that would meet the peculiar needs of their new social order.

Already they have made such progress that the British Trade Union Delegation of 1924 was able to report that “there has probably been no greater revolution of ideas than in the new educational system as practiced in Soviet Russia.” (Report p. 138.) Brailsford caught the spirit of the movement back in 1921. The Communist Dictatorship, he wrote, “is ripening the whole Russian people for responsibility and power by its great work for education.

It has, moreover, based its entire system of education, not on any principle of passivity, receptivity and discipline, but rather on ‘self initiative’ and activity.” (H.N. Brailsford, The Russian’ Workers’ Republic, p.78.)

There is as yet no Soviet educational system. The entire educational world of the Soviet Union is still in an experimental stage. Practice differs widely in schools that are located close together, in the same republic or even in the same city. Certain theories are commonly accepted, but there is a great variety in the interpretation that is put upon them. It is from this variety and from the discussion arising out of it that the Soviet education of the future is being built.

When the Revolution of 1917 freed the Russian school authorities from the bonds of the old order and threw upon them the responsibility of formulating a new method of education that would meet the needs of a workers’ republic, they began combing the world for suggestions. Books on psychology, pedagogy and educational method were translated from German, French and English. The work of American schools received special attention. Kilpatrick, Thorndike, Dewey and other American educators are almost as well known in the Soviet Union today as they are in the United States. All of these foreign methods and theories were examined and valued. Extensive experiments have been made with all of them in the Soviet schools. As a result certain lines of Soviet educational being inaugurated by the school authorities.

The Soviet Union is today an educational laboratory. Experiments are under way with subject-matter, with methods of instruction, with social organization among the pupils, with the organization of educational workers, with the organization of school directing committees and with e problem of opening the higher schools to the workers and peasants. In none of these fields has any permanent system been established. In all of them the educational authorities are looking for the correct answers to their questions and their needs.

Some of the older educators are non-plussed and discourage by this lack of unity and of established form in the Soviet educational institutions. One of them, who had been a professor of pedagogy for many years said: “There is no educational system in Russia today. There is only a religion. There have been and still are good experimental schools in the Soviet Union, but the general educational system is in hopeless chaos.”

Another professor of pedagogy was more realistic: “You will have great difficulty in understanding what is going on here in the educational institutions. We do not understand it ourselves. Come back in fifteen or twenty years, and by that time we may have a school system. We have none today.”

It is that very fact that makes the Soviet schools so important to educators in other parts of the world. Soviet school authorities have no system. They have been compelled to start from the bottom, in the second decade of the twentieth century, with the educational experience that has been accumulating in all parts of the West during the past thirty years as a background. Today they are working with desperate energy and enthusiasm to create a system. If they can have an uninterrupted decade, they should be able to produce educational forms that will serve as patterns wherever capitalism gives place to the workers’ state.

Educators in every other country labor under the weight of mountain-high traditions. Their hands are tied with educational conventions. Established economic institutions have a firm grip on the educational system, and refuse to permit serious modifications in its forms or activities.

Soviet educators were freed from most of this institutionalism by the Revolution. The wiping out of old economic and political forms enabled them to start afresh. Probably not since the period of the French Revolution have educators been so free, anywhere in the world, to shape their work in accordance with current social needs.

Two problems are paramount; (1) to determine what these social needs are; (2) to decide how best to meet them. It is the answer to these two problems that Soviet educators are now seeking.

Educational experimentation in the Soviet Union is not confined to the schools. The school system proper makes up only one part of Soviet educational activity. Educational work is being carried on through the following channels:

1. The educational institutions directly under the control of the departments of education. This includes:

a. Pre-school work with children between three and eight years of age.

b. The formal school system, extending from the first grade of the elementary schools through the higher technical schools, universities and institutes.

c. Experimental schools within this school system.

d. Extension and extra-mural work.

e. Publications.

f. Theatres, libraries, museums.

2. Villages are establishing reading-rooms, libraries, and local culture centres where lectures, classes and other educational activities are carried on.

3. The trade unions have an elaborate and very extensive system of clubs, classes, libraries.

4. The Communist Party, the Young Communists and the Pioneers carry on political education, classes for the liquidation of illiteracy and some technical training classes.

5. The army is an active educational centre. The recruits are expected to learn reading and writing within the first thirty days of their stay in the army. They also have regular classes in social science, in technical and cultural subjects.

6. The Soviet press, for the publication of books, magazines and newspapers, is on an educational basis. It is linked with the formal school system and maintains a definite educational aim.

7. Other organizations like the co-operatives, the departments of health and the departments of agriculture carry on educational work on a large scale.

Here it will be possible to write about only that portion of Soviet educational work which is directly connected with the education of children through the schools. The other fields are no less important. In many ways they are even more worthy of attention because they are more unique, but it is not possible to cover the whole field in one small book, and I have not the material which would be needed in order to treat them adequately.

About the formal school work for children that is being carried on by the Soviet educational authorities I cannot write with any great exactitude. I had neither the time nor the means to give the matter careful study. I can merely relate what I have seen and heard in the institutions that I visited. Some of them were undoubtedly ‘‘show” schools. Others were unquestionably below the level of average Soviet education. Some well-staffed teachers’ college should put a corps of investigators into the Soviet Union and keep them there until they have a good picture of what is going on in the schools. The task of making such a study is quite beyond the energy of an individual.

My inquiry into Soviet education began quite accidentally. A year ago, while working over some material on education, I came to a place where I needed a little data on Soviet schools. I went to the libraries, naively expecting that it would be a simple matter to locate an adequate amount of information on the subject. What was my surprise to discover that there was practically no literature, either in French, German or English, on the work that the Soviet schools were doing. With the exception of a few chapters here and there, written by visitors to the Soviet Union who were not particularly familiar with educational matters, I could find nothing worthy of note. The educational periodicals were as barren as the bookshelves.

After briefing everything that I could lay my hands on and comparing it with what I needed, I realized that if I wanted to write about Soviet education, there was only one way to do it. That was to go to Russia.

Last winter I made the trip, taking with me the notes that I had been able to gather from my reading in American libraries. During two months I visited Soviet schools constantly, in villages, towns and cities, from kindergartens to universities, along a line of travel covering more than three thousand miles. Sometimes I went “officially” to a school, with a representative of the board of education. At other times I dropped in casually, walked into a class-room, presented my credentials and asked whether I might stay. I did not meet with a single refusal. Throughout this trip I talked with school people from janitors to superintendents; from kindergartners to university students. I do not pretend that I got the whole truth, even about those of the Soviet schools that I saw, and I saw only a tiny fraction of the total number. But I learned enough to realize that the notes I had taken on my American reading were not worth ten cents a pound. I was compelled to learn the lesson of Soviet education from the beginning and I am quite sure that much of it is still far from accurate.

Some of the readers who scan these pages will already have read about Soviet education, and they will wonder why what is written here does not agree with many of the things they have read elsewhere. There are three answers to such readers. The first is that many of those who have written on this topic in the educational periodicals have not been in the Soviet Union since the Revolution; the second answer is that the educational work there is changing so rapidly that what is true of it today may not be true tomorrow; and the third answer is, that if you are a trained educator, and are really interested in the question, you should take off a few months and see for yourself. The experience will be well worth all it costs.

It is twenty-two years since I began to teach school. In the interval I have visited many schools in many countries. In all of my experience I have never seen anything that paralleled the educational work that I saw going on in the Soviet Union.

Readers will be tempted to conclude from this statement that I regard the Soviet Union as an educational paradise. Quite the reverse. It would be hard to find poorer equipment than that in many of the Soviet institutions. Buildings are old. Benches are worn out. Black-boards and books are lacking. Teachers and other educational workers are badly paid-sometimes, for months, unpaid. Only about half of the children of school age in the Soviet Union can be accommodated in the schools. Lunacharsky, Peoples’ Commissar for Education, estimates that the Union is now short 250,000 teachers. Even if they had these teachers, they would have no class rooms in which to put them. Probably there is no large country in Europe where educational conditions are physically worse than they are in the Soviet Union.

Soviet educational institutions are not a paradise. They are a battleground. On this battleground an entire people is fighting against ignorance, using all of the weapons that the modern educational world has invented and forged for the purpose, and incidentally, inventing and developing some weapons of its own.

Responsible leaders in the Soviet Union have been directed to see to it that no more generations of Russian children grow up in ignorance. They are determined that the education which they provide for the next generation shall be the best that can be found, so they are searching the world, and experimenting at home, in their efforts to build an educational system capable of training children for a new social order.

Educational achievement in the Soviet Union is as yet negligible. The struggle that is going on there to secure educational results is one of the most fascinating dramas I have ever witnessed. Judging from a brief two-months survey, it will also be a fruitful source of educational knowledge and progress.

Visiting schools in the Soviet Union is an experience,–stimulating, unforgettable. The children are as glad to see you as are the teachers.

Outside of the big centres, the school children have never seen an American. They were babies when the war broke out, and they have been blockaded away from the West ever since. But they have read Jack London and Upton Sinclair. They know of Henry Ford, of the Ku Klux Klan, and of the “Monkey Case” at Dayton, Tennessee. They have seen Charlie Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks on the screen. They have pictures of Indian chiefs in their war-paint, of cattle round-ups and of all the doings in the “Wild West.” This is quite generally true of the children in the upper elementary classes and in the high schools. Consequently these children ply the visitor with innumerable questions. Nor are they ignorant of politics and economics. They want to know why the United States does not recognize the Soviet Union, how strong the radical movement is in the United States, and why the American Federation of Labor is so conservative. These young folks have real international interests. They have heard and read a great deal and they are anxious to know more.

When you get through looking over the class work and talking to the pupils, the teacher takes you to one side and begins: Just how is the Dalton plan succeeding in the United States? Where is the project method being tried? What is being done with intelligence tests in America? Who is your best man on physiological psychology? How much self-government do you have among the children in your schools? These questions are not asked by every teacher, of course, but in practically every school there are specialists who are making a study of some phase of education. These matters are discussed constantly, and any light that an outsider can throw on them is eagerly welcomed.

There was hardly a school person with whom I talked in any detail who did not say: “Is that all you wanted to ask? Well, since you have finished with your questions, I should like to ask some myself.”

Another sentence was repeated again and again: “Now that you have seen the school work, would you mind telling us what you think of it, and what suggestions you have to make?” All of the school people seemed to be searching for knowledge and very eager to get new ideas.

Sixty days in the Soviet schools did not permit me to make an investigation of Soviet education. In all I saw only about seventy schools. I did not study any of them thoroughly. The following pages contain merely a series of pen-pictures. I feel justified in printing them, however, because there is little first-hand information in English on Soviet education, and because I believe that the educators in other countries should realize the importance of the educational experimenting that is now taking place in the Soviet Union. To the scientific student of education the Soviet schools present a rare opportunity. There his pet theories and programs are being tried out on an immense scale. The Soviet Union is, at the moment, the world’s largest and most important educational laboratory, and the educational organizations, institutions and departments of the leading countries should have their experts in the Soviet Union now, collecting information and making suggestions.

Education in Soviet Russia by Scott Nearing. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf