A seemingly small episode between the reformist Victor Berger and the revolutionary Bill Haywood at 1910’s Socialist International Congress, but one so telling that Solon De Leon wanted to write it down for posterity.

‘An Episode at the Copenhagen Congress’ by Solon De Leon from The Weekly People. Vol. 20 No. 33. November 12, 1910.

There is one episode occurring at the recent International Socialist Congress at Copenhagen, and alluded to in the report of the Socialist Labor Party’s delegate, which I believe worthy of more extensive description, and preservation in the archives of the movement.

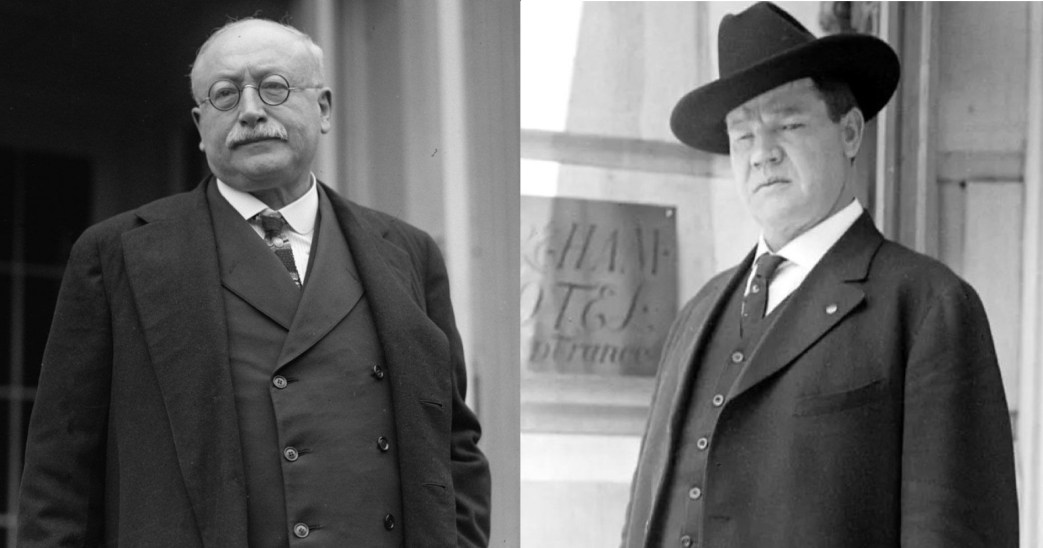

It was the evening of the fifth day of the sessions. That afternoon, in response to De Leon’s summons that the S.P. delegation tell what they were willing to do in the matter of Unity, Hillquit (“I never would have taken the floor except for the direct challenge of the previous speaker,” he truthfully told his auditors) had delivered one of his characteristic speeches. There was already, he declared, practical Unity in America. At the convention held in 1900, when the Socialist party was organized, all the various groups had combined. Only one dissident set had remained outside, the S.L.P. That had gradually dwindled down till it was composed of just one wicked man, who wouldn’t come in and be good. But even he was welcomed–provided he would drop his new-fangled ideas on the economic movement, and stop attacking and antagonizing the trade unions. Following Hillquit, Berger had spoken, also loudly scouting the idea that there was need for any further unity in America. Finally Haywood tried to get the floor, but he not having notified the chairman soon enough, the speakers’ list was closed, and he was denied the opportunity.

That evening, in a contiguous abandoned royal palace, the Congress Committee on Trade Union Relations was in session, Berger and Haywood appearing as delegates of the S.P., and Mrs. Olive M. Johnson for the S.L.P. The discussion turned upon the slight support given the Swedish strike by the unions of England; and America incidentally came in for some of the same censure, but not so heavily. After a smooth but empty speech by W.C. Anderson, the British Laborite, Haywood rose in the defense of the United States.

“You people here,” he said, “seem to think that we in America have a united labor movement. That is not the case.” Here his emphasis was emphatic “What we have in America is a systematic division of labor. The great American Federation of Labor, and the independent craft unions modeled after it, accomplish no other purpose than to keep the workers separated. These unions are not in any sense organizations of labor. They are capitalist institutions, controlled and run in the interests of the capitalist class. They do not seek to take the workers. in, but to keep them out. In many cases the unions have what they call ‘restriction of apprentices’ by which they deliberately prevent men from learning the trade. Added to this, they have severe technical examinations,’ which they render more severe at will, thus making it difficult for even an expert to join. If they fail in this way, they then raise a wall of high initiation fees about themselves, making a man pay $100, in some cases, before he can be admitted to membership. And when all this fails to protect their little circle of jobs, they ‘close their books,’ and inform the workers who are begging to be organized that they won’t take them in on any consideration,

“More than this,” Haywood continued.

“Due to the craft system of organization, and the method of arranging contracts to run out at different dates, the American unions allow themselves to be used to break every strike that comes up. We constantly see engineers scabbing it upon switchmen, carpenters scabbing it upon bricklayers, powerhouse men upon trolleymen. The labor movement in America will never be a united force till all the workers in one industry are united into one great union nationally, and even internationally. The present unions are an actual detriment to the working class.”

The room was thronged by S.L.P. and S.P. members, besides about 150 European committee-members and visitors. The interpreter for the committee was Hendrick De Man, a young Belgian fully in sympathy with the S.L.P.’s trade union position. He had heard Hillquit’s and Berger’s flim-flams in the full Congress, and his spirited rendition of Haywood’s remarks into French and German made the European representation sit up and listen in amazement–so much so that Temporary Chairman Troelstra, a Dutch delegate and one of Hillquit’s staunch supporters, tried to interrupt the translation into German by crying out “Enough!” “Too long!” “Not necessary!” Calls, however, for the continuation of the speech were heard, and De Man was allowed to make a brief but forcible summing up.

All through this scene Berger sat like a duck in thunder–a circumstance which did not prevent him from pulling his chair up closer to Haywood’s, and twining his arm around the other’s neck like a honeysuckle. His uneasiness was in no wise decreased by Mrs. Johnson’s going over the pair and saying, “Why, Mr. Haywood–your Genosse Hillquit would have your head off if he heard that!” Clearly something had to be done. The opportunity soon came, or, rather, Berger made it. Calling to the fore a resolution he had previously introduced indorsing a contemplated European seamen’s strike, the originator of the “Milwaukee idea” took the floor and argued long and fervidly for its adoption. Several times, both before and after this, did he speak in the Congress; but never did he put half the vim into it that he did on this occasion.

“There is a widespread belief, both here and in America,” he declared in German–both he and Hillquit always played to the German side of the house by speaking in that language first, and later translating into English–“that we Socialists are the deadly enemies (Todefeinde) of the trade unions. This idea must be wiped out. I beg of you, pass this resolution. Then when I go back to America, and the Socialists are charged with assailing the trade unions, I will be able to show that we are not the enemies of the unions, but their very best friends.”

The episode– Haywood’s crashing truths, their attempted choking off by Troelstra, and Berger’s desperate attempt to polish them over–was complete. Branting, a stalwart Swedish Social Democrat, and several others who are keeping track of events in America and who were present, all commented, in private conversations on the way home, on the complete lie given by the affair, to the position assumed by the S.P. representatives in the full Congress. The exposure of S.P. duplicity and internal dissension could not have been better done.

The next day when I spoke to Haywood at the American table about his stand the night before, “That’s the way I’ve always talked, and always will,” said he, and added that he had intended to utter the same words the previous day at the Congress when he had been unsuccessful in obtaining the floor. The effect of the same declaration, made from the more resounding tribunal of the full Congress, and coming directly after the Hillquit-Berger allegations, would have been inestimable.

But Berger, when one wished to speak with him on the occurrence, threw up his hands in impatience, and fled.

S.D.L.

New York Labor News Company was the publishing house of the Socialist Labor Party and their paper The People. The People was the official paper of the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP), established in New York City in 1891 as a weekly. The New York SLP, and The People, were dominated Daniel De Leon and his supporters, the dominant ideological leader of the SLP from the 1890s until the time of his death. The People became a daily in 1900. It’s first editor was the French socialist Lucien Sanial who was quickly replaced by De Leon who held the position until his death in 1914. Morris Hillquit and Henry Slobodin, future leaders of the Socialist Party of America were writers before their split from the SLP in 1899. For a while there were two SLPs and two Peoples, requiring a legal case to determine ownership. Eventual the anti-De Leonist produced what would become the New York Call and became the Social Democratic, later Socialist, Party. The De Leonist The People continued publishing until 2008.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-slp/101112-weeklypeople-v20n33.pdf