The first two chapters of Nearing’s early work on Soviet education.

‘I. A Dark Educational Past II. The Soviet Educational System’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

I. A DARK EDUCATIONAL PAST

Educationally, in the opening years of the twentieth century, Russia was one of the darkest countries in the world. The extent of illiteracy among army recruits gives a good idea of the relative position that Russia occupied in this respect among the nations of Europe. Among Belgian recruits, eight per cent were illiterate; among French recruits, four per cent; among recruits from the United Kingdom, one per cent; among German recruits, one-twentieth of one per cent, but among Russian recruits, 62 per cent of the men were illiterate.

This illiteracy was perpetuated in Russia as a part of the governing policy of the Czarist bureaucracy. “The Imperial Government, far from trying to stimulate educational activities, did everything in its power to hamper the work of enlightenment.” (Leo Pasvolsky, Educational Rev., vol. 62, p. 210, 1921.)

“Education was intended for the privileged classes only.” (Theresa Bach, Educational Changes in Russia, U.S. Dept, of Education, Bui. 37, 1919, p. 4.) Obstacles were placed in the way of peasant children and working-class children who desired to acquire higher education. “The fourth Minister of Instruction, Shishkov, with the approval of Czar Alexander and in his presence, issued the following statement:

“Knowledge is useful only, when, like salt, it is used and offered in small measures according to the people’s circumstances and their needs…To teach the mass of people, or even the majority of them, how to read will bring more harm than good.” (Ibid.)

The proportion of Russian children in school was extremely low, A.N. Kulomzin, a Russian educational authority, estimated in 1904 that twenty-three per cent of the entire population of the United States were in school. In the German Empire, the percentage in school was nineteen; in England, sixteen; in France, fifteen. In Russia, 3.3 per cent of the entire population were in school. (V.G. Simkhovitch, Educational Review, May, 1907, p. 520.)

The officials of the Central State exercised an immense power over these meagerly attended schools. They regulated the subjects taught, the activities of the teachers, and the conduct of the students.

Here is a school program designed for primary schools in which the children stayed for at least three years:

Religion—6 hours per week

Church Slavonic—3 hours per week

Russian—8 hours per week

Writing—2 hours per week

Arithmetic—5 hours per week

“Three hours a week in addition are assigned to church singing.” (Education in Russia, British Board of Education, Special Reports, 1909, p. 240.) This course of study, intended for the children of more than four-fifths of the Russian people, included neither history, civics, natural science, nor any form of hand training. It gives an idea of the limitations imposed by the Czarist State upon the things that could be taught in Russian schools.

Teachers under the Czar were subject to constant surveillance by government inspectors. In the state schools this surveillance was complete; in the zemstvo schools and the church schools it was only a little less thoroughgoing. The teachers were wretchedly paid. In the period immediately before the Revolution French teachers received 481 rubles per year; Dutch teachers, 875 rubles; English teachers, 1665 rubles; and Russian teachers, 360 rubles. The year before the war, a survey published in Russkaya Shkola showed that a single teacher living in a village required about 536 rubles, while a family man needed 1073 rubles. (M.G. Hindus, The Russian Peasant and the Revolution, N.Y., Holt, 1920, p. 57.)

Only a few Russian school children entered the higher schools and colleges. The Universities were practically closed to working-class children.

Among the few students who reached the higher educational institutions, social discipline was rigid. This was due in part to the student disorders which were so common in Russia during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The British Board of Education Special Report on Russia refers to these students’ disorders in some detail. Among other information it gives the rules for students that were issued under the sanction of the Minister of Public Instruction and imposed on the students of all universities:

“13. The presentation of addresses and petitions signed by several persons, the sending of deputations, the exhibition of any notices whatever in the name of the students are forbidden.

“14. Within the buildings, courts, and grounds of the university the organization of students’ reading rooms, dining or food clubs, and also of theatrical representations, concerts, balls and other similar public assemblies not having a scientific character is absolutely forbidden.

“15. Students are forbidden to hold any meetings or gatherings for deliberation in common on any matters whatsoever or to deliver public speeches, and they are like- wise forbidden to establish any common funds whatsoever.

“16. Students are forbidden to take part in any secret societies or clubs such as zemliachestva and the like, even though these may have no criminal object, or even to join any legally recognized society, without obtaining express permission in each individual case from the authorities of the university concerned.” (pp. 445-6.)

Against this coercive university discipline the students revolted time after time. It was aimed to prevent them from thinking. In practice it served to stimulate their interest in a new world order.

Dominated by a ruling class shibboleth that education must be confined to those who were intended to rule, with only a tiny proportion of Russian children attending school, teachers underpaid, harassed and restricted, students subject to continual surveillance and responding by intermittent revolts–this was the educational system of Czarist Russia. Against the background of this dark educational past flashes the blinding light of the Russian Revolution.

Educational enthusiasm swept across Russia with the Revolution. The people had been kept in ignorance. Only a few of them had been able to dip into the book of knowledge. Now the whole volume was in their hands and they might use it as they would.

Higher institutions were thrown open. Students flocked into them by thousands–students many of whom had grown old without ever having learned to read and write–students in search of knowledge. In the first enthusiasm of the Revolution great plans were made. At a Pan-Russian congress on education held in Moscow during August, 1918, Lunacharsky, Krupskaya and others painted, with broad strokes, the intellectual and esthetic life of the new Republic.

But means were lacking. Financial bankruptcy, civil war, famine, economic disorganization all took their toll during those three critical years that followed 1918. In 1921 the Soviet Union turned the corner economically. From that time forward the economic foundation has been laid for the new educational system.

Since the days immediately following the Revolution, Russian educators have been striving to utilize the educational machinery to prepare the people for their own emancipation. Their first effort was to make it possible for all to have an education. For this purpose they aimed to establish “a single absolutely secular school” that would be thrown open to the humble and the poor. (Theresa Bach, Educational Changes in Russia, U.S. Bur. of Education, Bul. 37, 1919, p. 3.)

When H.N. Brailsford made his study of the Soviet state in 1920 he came to the conclusion that the Soviet authorities were trying to “base the greatness of the world’s first Socialist Republic upon a generation of children who will be mentally and physically the superiors of the men and women of to-day.” (The Russian Workers’ Republic, London, Allen & Unwin, 1921, p. 76.)

One of the first acts of the Provisional Government of 1917 was the secularizing of church schools. “The final blow inflicted on the ecclesiastical school authorities came from the Soviet of the People’s Commissaries, which in its session of January 20, 1918, officially proclaimed the separation of church and school. The immediate effect of that measure was the elimination of the teaching of religion and theology in all the public schools and the doing away with all discrimination between pupils on religious grounds.” (Theresa Bach, supra, pp. 5-6.)

Control over Soviet education is now localized in each of the republics that compose the Soviet Union. In this respect the organization of affairs in the Soviet Union follows the line laid down in the organization of the Government of the United States. Matters of local concern are handled locally, leaving only matters of general concern to be dealt with by the central authorities. In the Soviet Union education is one of the questions that is left to the local authorities.

Each republic has its department of education. Each city likewise has its educational department. Education is organized by counties, by regions and by districts. The important political areas all have their educational functions.

All educational matters that are of purely local concern are decided locally. Following out this principle of local self-determination the schools in the Ukraine are now requiring all of their pupils to learn the Ukrainian language. Schools in Tiflis are conducted in Armenian, Turkish, Russian and Georgian because of the large populations that speak only one of these languages. Local interests therefore determine the general character of local educational functions.

This does not mean that there is no common aim in the Soviet schools. Behind them is the unified structure of a workers’ and peasants’ government. Congresses and conferences are being continually held. Various economic and political organizations such as the Trade Unions and the Communist Party, that are Union-wide in their scope, bind the whole educational structure together. It remains true, however, that there is no coercive central control of education in the Soviet Union.

Education is somewhat centralized within each of the republics. The four “big republics” of which the Soviet Union is composed are the Russian Republic, the Ukraine, White Russia and Transcaucasia. An idea of their relative importance may be gained from the following figures:

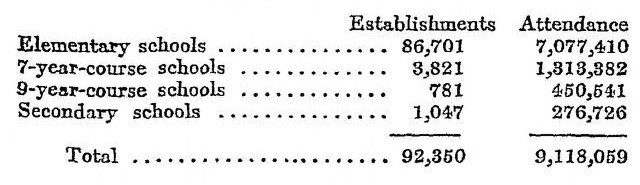

STATISTICS OF COMMON SCHOOL EDUCATION FOR THE SCHOOL YEAR 1924-5

In addition there were 3,338 kindergartens with 257,715 pupils, 1,164 combined kindergartens and creches with 61,450 children, 264 settlements for normal children with 46,735 children, and 540 settlements and institutions for defectives with 33,826 children.

On January 1, 1925, there were 3,030 vocational schools with 283,506 students, 114 workers’ colleges with 43,109 students, 903 establishments for technical education with 162,197 students, 170 colleges of higher education with 170,811 students.

Within each republic the school work is organized, just as it is in other countries, under a secretary (commissar) of education, and an educational department. The chief subdivisions of the Department of Education of the Russian Republic are:

1. A department of organization and administration.

2. A central department for social education.

3. A general department for professional education.

4. A chief committee on political education, including in its membership representatives from the trade unions, the Communist Party, the co-operatives, etc. (It should be noted that many of the subdivisions of the educational department have representatives of other organizations and departments on their committees.)

5. A chief department of scientific institutions, with sub-divisions on scientific institutions and on museums.

6. A chief department for the inspection of literature and editorship.

7. The scientific state council, with a. A section on scientific pedagogy. b. A section on scientific technology. c. A scientific political section. d. A scientific arts section.

This is the central planning department for the educational work of the Republic.

8. Three economic undertakings are now being carried on under the direction of the department of education: a. Gosisdat—the state publishing house. b. Goskino–the state moving picture enterprise. c. The department of state theatres.

Directly or indirectly this organization touches all of the educational work that is going on in the Republic. Where it does not have mandatory authority, it acts in an advisory capacity. It is the state, organized as educator.

This is an outline of the educational organization for the entire Russian Republic. Within the Republic, each subdivision—each region, county, city and village—has some form of local educational organization with a greater or less amount of local autonomy. Moscow, with its population of two millions, has a very extensive school system. Leningrad also has a large educational plant. Both cities are in the Russian Republic, and yet the educational work done in the two cities is in many respects quite different. The principle of working class education remains the same. The local practice varies.

There is nothing new nor unusual in this form of central and local educational administrative organization. It exists in many countries. Soviet educators are making their contribution in the work that is being done in the schools.

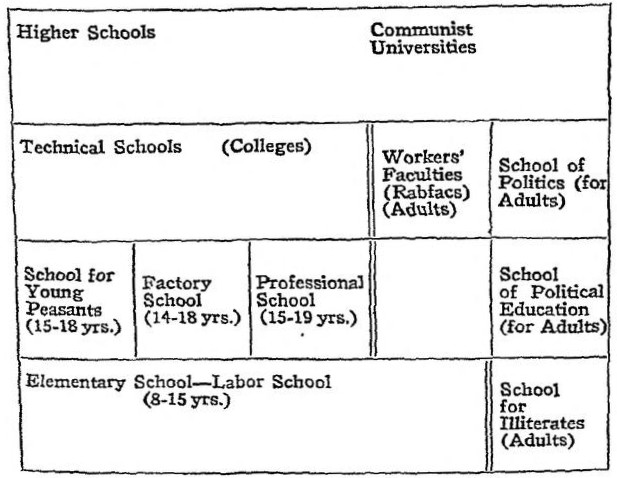

Soviet educational authorities have a dual problem: they must educate the new generation of children; they must also educate the adults who, under Czarism, missed an opportunity to attend school. Both problems are insistent. The educational authorities of the Russian Republic link them in this way:

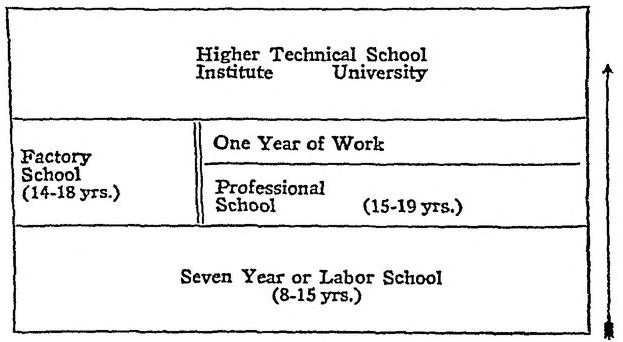

Ukrainian educational authorities modify this scheme in two important ways: First, they make a break of one working year between the professional and the technical schools. Second, they concentrate all of their attention on technical work and higher scientific work, thus practically eliminating the university. Their scheme for child education, as outlined to me by two of the leading men in their school system, is as follows:

Education of the adult population, whether in forms of political education or in the rabfacs, is regarded as of only temporary importance. With the coming of a generation of educated children the regular educational system as outlined above will do this work.

Looked at from one point of view these general outlines mean little. They do not represent accomplishment but only striving. They indicate, not what the Soviet educational authorities have done, but what they hope to do. And it goes without saying that in the Soviet Union, as elsewhere, accomplishment usually lags behind programs. Still they give a picture of the educational trend.

There are a number of terms employed by Soviet educators that are not commonly used in American educational literature. Some of these terms have quite different values in various parts of the Soviet Union at the present time. For the sake of clarity, it is therefore necessary to define the terms that must be used in describing Soviet education:

II. THE SOVIET EDUCATIONAL STRUCTURE

Pre-school education refers to educational work with children between the ages of three and eight. Children of less than three years are under the boards of health. Children of eight come under the compulsory education law. Pre-school education includes kindergartens, nurseries, playgrounds, story telling, trips and excursions, the preparation of literature for young children.

Mass education is the education that all children are supposed to have. It includes ages from eight to eighteen or nineteen. All children in the Soviet Union will ultimately go to school during these years. For the present the lack of buildings and of equipment make general compulsory education impossible.

Labor schools are the schools that take children from eight to fifteen years. They are also called Seven Year Schools. The work that they do is described as Social Education. They are the elementary schools of the Soviet Union.

Social education refers to the work with children between eight and fifteen years. This is the education given by the Labor Schools or Seven Year Schools.

Professional education is the specialized training given to students between the ages of fifteen and eighteen or nineteen. Professional schools are very much like American technical high schools, except that they are somewhat more specialized. They include Factory Schools. Professional Education is intended to train disciplined, efficient workers. According to the Soviet educational plan, all workers will complete a course of training in a Professional School.

Factory schools are run in connection with some industrial enterprise. The students usually include all of the apprentices at work in the enterprise. Students are from fourteen or fifteen to eighteen or nineteen years of age. They spend four hours of each day in the school and four in the factory.

Higher technical schools are those institutions of American college grade that take students at about eighteen years of age, when they have completed the Mass School, and give them some special training in engineering, in pedagogy, in transportation, in art, or in some other subject. These higher technical schools are not a part of Mass Education. They are intended only for students who display special aptitudes, and who are apparently able to benefit by special training.

Universities are institutions doing general educational work of what would be college grade in the United States.

Institutes are either research laboratories or else they are institutions that carry on research and teaching work of a grade equal to that of an American graduate school.

Rabfacs or Workers’ Faculties are higher technical schools designed to take care of workers who have never had any educational opportunities, and who are sent direct from factories into the Rabfac to receive a technical education.

There is as yet no uniformity in the use of the terms, even in the same Republic. There is a general tendency in their use, however, which I have tried to indicate in these definitions.

Soviet education is not a complete departure from the educational systems of the West. It is an adaptation of these systems to the needs of a new type of society, and in some respects it involves breaking virgin soil. The general organization of educational administration still follows western lines.

Education in Soviet Russia by Scott Nearing. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

Education in Soviet Russia by Scott Nearing. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf