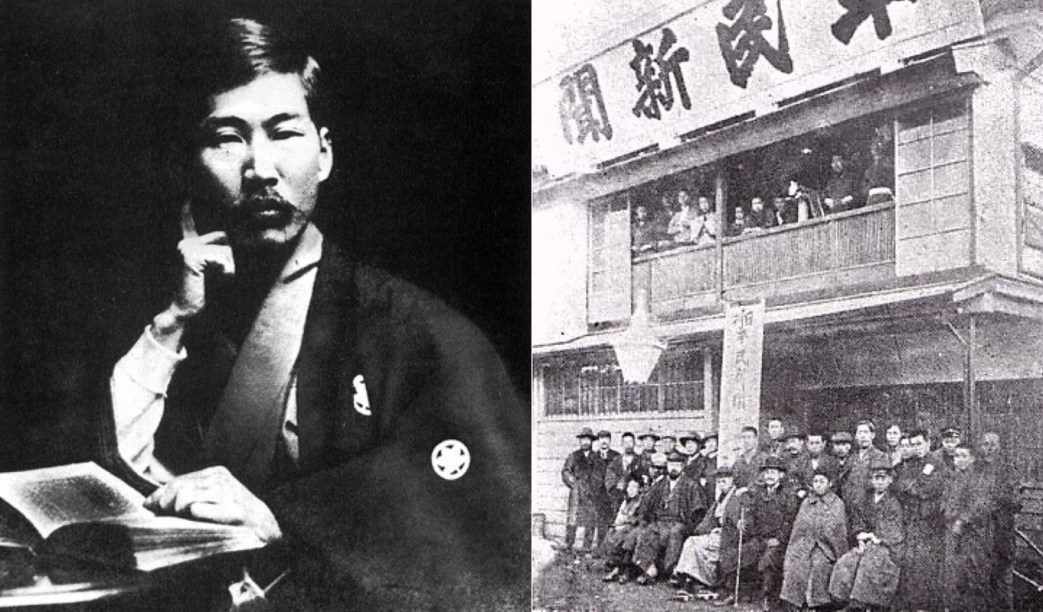

A central figure in modern Japanese radicalism, Kōtoku was editor of Heimin Shinbun (News of the Common People) who would be executed for his revolutionary politics along with eleven other comrades in the 1911 High Treason trial. Here he writes on the outbreak of 1904-5’s imperialist war between Russia and Japan.

‘Japanese Socialists and the War’ by Denjirō Kōtoku from International Socialist Review. Vol. 4 No. 12. June, 1904.

RECOGNIZING that war always brings with it general misery, the burdens of heavy taxation, moral degradation and the supremacy of militarism, the Japanese socialists have stood firmly against the popular clamor for war with Russia, and done their best to point out that all Russian people are our brothers and sisters, with whom we have no reason to fight. But the entire Japanese populace was intoxicated by the enthusiasm of so-called patriotism. Even workingmen did not realize what a deplorable thing war was for them, and dreamed that in some way their condition might be bettered.

While the nation, however, is congratulating itself over the naval victories, the economic effects of the war have begun to be felt on all sides in such a way as to justify the socialist’s prophecies. The families whose breadwinners have been required for the army are suffering for want of the necessaries of life. The demand for goods used in daily life has already fallen off in many directions, so that numerous factories are closed and manufacturers have been bankrupted. Hundreds of thousands of workmen have been thrown out of work and are only living through the scanty gifts of charity. At Nishidin, a district of the city of Kioto, famous for its silk industries among foreigners, tens of thousands of unemployed weavers are living today on a rice gruel provided by rich philanthropists. Even this help will soon be withheld from them because of the great number of beggars, it is claimed, such a feast attracts. The poorest quarters of Tokio exhibit the most deplorable poverty and suicides and other crimes are increasing day by day.

To be sure the subscriptions for the war bonds were nearly four times as great as were needed, until the whole world was astonished at the ability of Japan to raise money at home. But the method of raising this, so far as I can learn, was largely compulsory to almost the same degree as the collection of taxes. Tin authorities throughout the country visited every house to persuade the communities to subscribe toward the war fund. Those who refused to accept this “official order” were denounced as unpatriotic. A peasant living in a village near Tokio is said to have been forced to subscribe 200 yen and having no money he attempted to secure the necessary funds by robbery, and was arrested.

All these facts, however, are not simply overlooked but are definitely concealed by the press corrupted by the bribery of capitalists and bankers. The House of Representatives was also frightened by the threat of government coercion and became a very faithful servant to the Cabinet accepting, in its entirety the bill proposing to increase the already heavy taxes by 60 million yen.

Indeed, the Japanese government really represents only the capitalist and landlord. The securing of universal equal suffrage becomes, therefore, the most important work for the Japanese socialist and the very existence of the Japanese Socialist Party depends on the outcome of this question. Under such circumstances, it is natural that the Socialist movement should meet with violent persecution. When the Heimin Shinbum, a weekly socialist paper opposed the war and the increasing of taxes, all copies of that issue were confiscated by the police, and the Tokio District Court of Justice, decreed the suppression of the paper and sentenced Comrade Sakai, one of the editors, to three months imprisonment. The case was at once appealed to the higher court of justice, so that the publication of the paper was allowed to continue and the term of imprisonment reduced to two months. Comrade Sakai began to serve the sentence on April 21st and at the time of writing this is still in prison at Tokio.

There are a few socialists in this country who are preaching socialism to the workingmen and the students. They formed a Social Democratic party on May 20, 1901, which was instantly suppressed by the government and the newspapers that published the Manifesto of the party were confiscated. But the foolish governmental policy proved to be the best means of waking up the people, and the Socialist Association, which has since been formed, is becoming the centre of the labor movement.

At present, there are two socialist papers in Japan, the monthly “Socialist” and the weekly “Heimin Shimbun” the former is owned by Comrade Katayama, who is now in the United States seeking to organize the Japanese immigrants of that country. The latter is published by the several members of the Socialist Association to which the present editor belongs and has a circulation of about 5,000 copies.

The regular meeting of the Socialist Association is held at the office of Heimin Shimbun. These meetings are devoted to lectures and debates. Monthly public meetings are also held for the promulgation of socialist opinions on current politics. It must be remembered that all of these meetings, however, are under close supervision by numerous police officers and secret spies, who have authority to stop the speakers, or dissolve the meeting, in accordance with an obnoxious law entitled, “a law for preserving public peace.”

The utterance of the words, “revolution,” “democracy,” “organization” or “strike” by any of the speakers is a penal offense. In this respect the Japanese government is certainly fifty years or a century behind the governments of Western Europe. The ruling power of Japan is, on this point at least, no less barbarous than that of Russia. The Czar is merely the head of the religious organization of his country, but the Mikado pretends to be God himself. Every school in Japan is a church in which the picture of the Mikado is worshipped and the religion of so-called “patriotism” preached. Some socialists insist therefore that social democracy can only be realized through the downfall of Mikadoism. But where sovereign power has rested upon a single head for several thousand years and most people have never even dreamed of changing the present dynasty, it is alarming to the whole country to attempt to introduce democracy even in the smallest degree. Consequently, we must wait patiently for the right moment. The realization of our idea is only a question of time.

D. Kotoku.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v04n12-jun-1904-ISR-gog-Harv.pdf