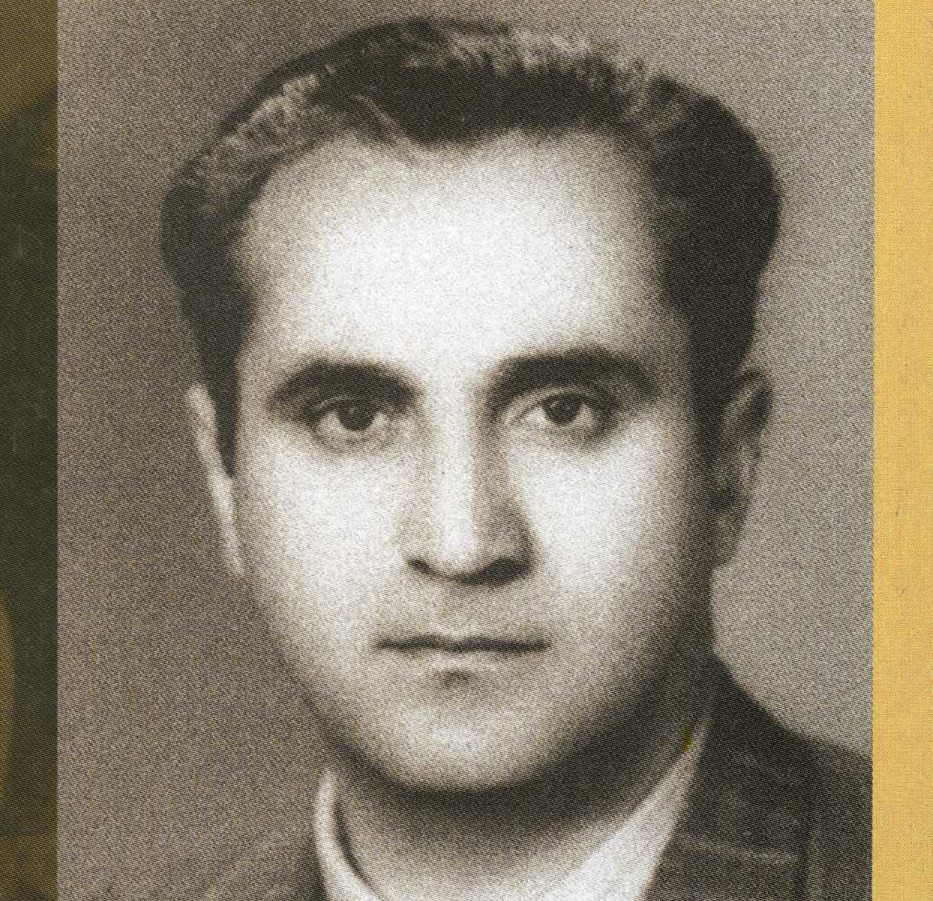

Najati Sidqi was a young Palestinian when he spent three years, from 1925-8, at the Communist University of the Toilers of the East, returning to Palestine to become the leading Arab voice in what was then a largely Jewish Communist Party of Palestine. This article was written just before his arrest by Mandatory authorities for which he spent two years in prison. In 1934 he moved to Paris where he became editor of the Comintern’s Arabic journal ‘The Arab East.’ Arrested and deported, he went to Uzbekistan where he became close to its leading Communists, themselves close to the remnants of the ZInivoviev Opposition. One of four Palestinian Arabs to fight in the Spanish Civil War he arrived in August, 1936 traveling to Morocco to propagandize against supporting Franco eventually running an anti-fascist radio station in Algiers. His anti-fascism led him to break with the party in 1939 with the signing of the German-Soviet Pact. After the war he became a writer and journalist, specializing in the incompatibility of Islam with fascism.

‘The Arab “Left” Nationalist Movement’ by Mustafa Sadi (Najati Sidqi) from Communist International. Vol. 7 No. 13. December 1, 1930.

In the camp of the Arab Left Nationalists in Palestine (the group of Hamdi-el-Husseini) there is taking place a continuous process of development and change in regard to both organisation and ideology. It is necessary to pay special attention to this process and to examine the causes which are effecting this differentiation among the Left Nationalists of Palestine, so as to be able to determine the policy and tactics which must be followed by the Communist Party of Palestine towards the Hamdi group.

The Hamdi group made its appearance in the political life of Palestine as an independent political group at the Sixth Congress of the Arab Nationalists in 1928. This group represented, on the one hand, the interests of the young Arab industrial bourgeoisie and, on the other hand, the interests of a section of the Arab intelligentsia and of the dissatisfied petty-bourgeois masses. It was founded as a left wing of the Sixth Congress of Arab Nationalists and carried on an active struggle against the right wing of the Congress, representing the interests of the trading bourgeoisie and the landowners.

The Sixth Congress of the Arab Nationalists was a Congress of consolidation of the right wing of the Arab Nationalist movement of Palestine. This consolidation was expressed in the healing of the split between the supporters of the ‘Supreme Muslim Council’ and the opponents of this Council, viz.: the Arab Executive Committee, which previous to the Congress had conducted a policy of ‘non-co-operation’ in relation to British imperialism. At this Congress, the overwhelming majority altered its relation to imperialism and adopted the following resolution:—

“The ten years’ policy of ‘non-co-operation’ has proved useless for the Nationalist movement. The Zionists are exploiting our position and are more and more drawing closer to the mandatory government. Consequently, it is necessary to alter the policy of ‘non-co-operation’ in the direction of cooperation with the British, limiting non-co-operation activity to the struggle with Zionism.”

When this resolution was voted upon, Hamdi and his supporters entered a strong protest and were almost expelled from the Congress hall, being regarded as “agents of Moscow.” After the conclusion of the Congress, Hamdi took up the struggle against national-reformism; he began to edit the paper Belsirat El Mustakim (“The Straight Path”) and more and more grouped around himself the dissatisfied anti-imperialist intellectuals. This was the first stage in the history of the Arab Left Nationalist movement after the betrayal of the Arab bourgeoisie and the passing of the movement from an anti-imperialist to an anti-Balfour struggle. This stage lasted till 1930. Its characteristic feature consisted in the uninterrupted struggle of the Left Nationalists with the mandatory power and with national-reformism.

During this period, the Left Nationalists showed a real self-sacrifice and devotion to the National emancipatory movement of the Arab countries. During the rising in Palestine, they played a fairly important part; they were the first to come forward openly calling upon the Arab masses to struggle first of all against British imperialism and not to allow themselves to fall a prey to the religious and national provocation of the Arab bourgeoisie or Zionist colonisers. On this account they were thrown into prison and their leader, Hamdi, was banished to the town of Nazareth for a period of one year.

The movement of the Left Nationalists raised the prestige of Hamdi in the eyes of the toiling masses who regarded him as their only saviour. Masses of people (mainly intellectuals) incessantly made their way to his place of banishment from all parts of Arabia in order to talk with him and to take his advice. The British imperialists were compelled to “liberate” Hamdi and to dispatch him to his native town of Gaza. The real purpose of this “liberation” was in order to remove him from the town of Nazareth, which is situated on the road to Syria, Iraq and Transjordania, and to banish him further away to this town of Gaza in the remote regions of South Palestine, surrounded by desert, and thus to make more difficult any consultation with him on the part of the leftwardly inclined Nationalist Arabs. These two years of struggle of the Hamdi group for the independence and union of the Arab countries represents, as already mentioned, the first stage in the movement of the Arab Left Nationalists, a stage of unorganised struggle, of individual demonstrations, without a Party, without a programme and without masses.

The second stage of the movement of the Hamdi group was actually a stage which was bound to decide the fate of this group. Hamdi and his supporters stood at the crossroads, not knowing which side to take, the side of the workers and fellahin Bedouin masses or the side of the national-traitor bourgeoisie. Nor did they know what slogans to put forward; for, indeed, the national-reformists were also making use of the slogans “Isteklaltan” (“Complete Independence”) and “Khurea” (“Freedom”), which by now had become very cheap. He and his group had to attempt to show that they were different from the camp of the National-traitors. Their endeavours in this direction were expressed in the struggle for the “defence” of the interests of the Arab workers and peasants, for their “emancipation” from the yoke of imperialism and of the Arab aristocracy. In his interview with the correspondent of the newspaper Mirat el Shark (“The Mirror of the East”), Hamdi declared:—

“In order to find a pretext for fighting the National emancipatory movement the imperialists always accuse us of Communism. They accuse us of Communism because we defend the interests of the Arab workers and peasants. They do not understand that the workers and peasants themselves constitute the people, and we are struggling for the emancipation of the people, against imperialism, against the Arab aristocracy which was in the past a weapon in the hands of the Turkish power as it is now in the hands of the mandatory government.”

At the time of the summoning of the first Arab Conference, Hamdi immediately became a “proletarian,” sending a telegram of greeting to the Conference in which he called upon the Arab workers:—

“Do not allow foreign elements to interfere with your affairs; you must yourselves defend your class interests. You alone represent the basis for the independence of our country.”

What do these words denote? They denote that he was desirous of distinguishing his line from the line of the Arab National traitors, that he had begun to struggle for the masses, for the hegemony of the movement of the Arab workers and peasants and petty-bourgeois strata of the Arab population, for squeezing out the influence and leadership of the Palestine Communist Party.

Hamdi, in making this speech, as a man imbued with bourgeois ideology, as a man who came from an aristocratic milieu and who defended landowners’ property in the soil, did not agree with the slogan of the agrarian revolution, considering that this slogan was ““premature’’ and that it was sufficient at the present time to restrict oneself to promises of definite reforms for the Arab fellahin, such as the abolition of ‘”ushor,” “chumsa,” etc. For a long time he wavered on this question. He took up a completely indefinite position in regard to the most serious questions determining the whole course of political events in Palestine, on the basis of which incessant conflicts were arising and which led to the rising of the Arabs in Palestine during the course of this year.

At present, the vacillations of Hamdi and his group between the camps of revolution and counter-revolution have ceased. The third stage has now opened in the life and activity of the left Arab Nationalists, the stage of splitting and differentiation. The left Nationalists have separated into a right and left wing. Hamdi is now heading the right wing of the left Nationalists. He has been converted from a “friend of the people” into a friend of the police and Arab compradores, into a lackey of British imperialism. He has refused now to be the secretary of the Anti-Imperialist League in Arabia. He now takes up a “distrustful” position in regard to the Palestine Communist Party and demands the imposition of his control over the activity of the Party. He now daily becomes more and more removed from Communism, declaring that Communism in fact represents a danger. He has now taken to entertaining with tea and biscuits the police and spies who come to make searches at his place.

Why has there been a split among the left Nationalists? Why has one section adhered to the workers and fellahin and the other to the National reformists? Undoubtedly, this split has deep-rooted causes, being based particularly on the fundamental formulation in principle of the agrarian question and of the methods of struggle for its decision. In the circumstances of the growing agrarian crisis in Palestine, of the uninterrupted paupersation of the fellahin masses, of the seizure by the Zionists of the land of the Arab peasants, and of the predatory taxation and merciless exploitation policy on the part of the Arab landowners, it is not possible for Hamdi and his supporters to remain neutral. They must choose for themselves one of two paths, either the land for the teilahin or the land for the landowners. It is on this basis that is taking place the present differentiation of the Hamdi group.

The left wing of the Hamdi group is in agreement with the slogan of “the land to the fellahin.” It carries on an active struggle with imperialism and with the Arab landowners. Thus, it has separated from Hamdi and has completely broken away from national-reformism. It has recognised that its aims can only be attained by union with the mass of workers and peasants, only by struggle for the dictatorship of the working class and peasantry in Palestine.

In order to characterise the ideological position of the left section of the Hamdi group, it is worth quoting the following extract from the article of one who was formerly Hamdi’s right hand, an article which appeared in the central organ of the Palestine Communist Party:— “Halaman” (‘Forward’). Analysing the position of the Palestine fellahin, the writer says:—

“I know of one merchant who made a loan to a single village of the sum of £500 sterling for a period of five years. At the end of the allotted period, this sum had been converted into 41,800 sterling. Owing to the usurious interest, the population of the village was compelled to sell up all its products, and some of them to sell all their possessions, but still they were not able to repay the debt. Our peasantry are dying from famine, the imperialists are sucking their blood, the Arab feudal lords are selling the interests of the people. Only revolution can alter this position.”

It is evident from this what a contrast exists in regard to the agrarian question between the right and left wings of the Hamdi Husseini group. The Communist Party of Palestine must draw from it the necessary conclusions in regard to principles and tactics in order that they may adopt a correct position in regard to both wings. The Communist Party of Palestine must now begin an exposure of Hamdi and of all the right-wing elements. as capitulators before imperialism and national-reformism, as traitors to the essential interests of the overwhelming majority of the Arab population, i.e., the peasant masses.

Primarily, they must warn the Arab toiling masses against the left phrases which the capitulators will still continue to utilise, at the same time adopting flexible tactics in relation to the left wing of the Hamdi group, drawing them into the work, especially of the League Against Imperialism, utilising them to the maximum extent possible for work among the peasantry and Bedouin masses, assisting them to create broad, mass anti-imperialist organisations and stringently controlling their activities. Only in this way will the Communist Party of Palestine be able to control these revolutionary forces for strengthening its positions among the Arab masses for the decisive struggle against British imperialism, against Zionism and against the Arab feudal and compradore elements.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This The Communist was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-7/v07-n13-nov-15-1930-CI-riaz-orig.pdf