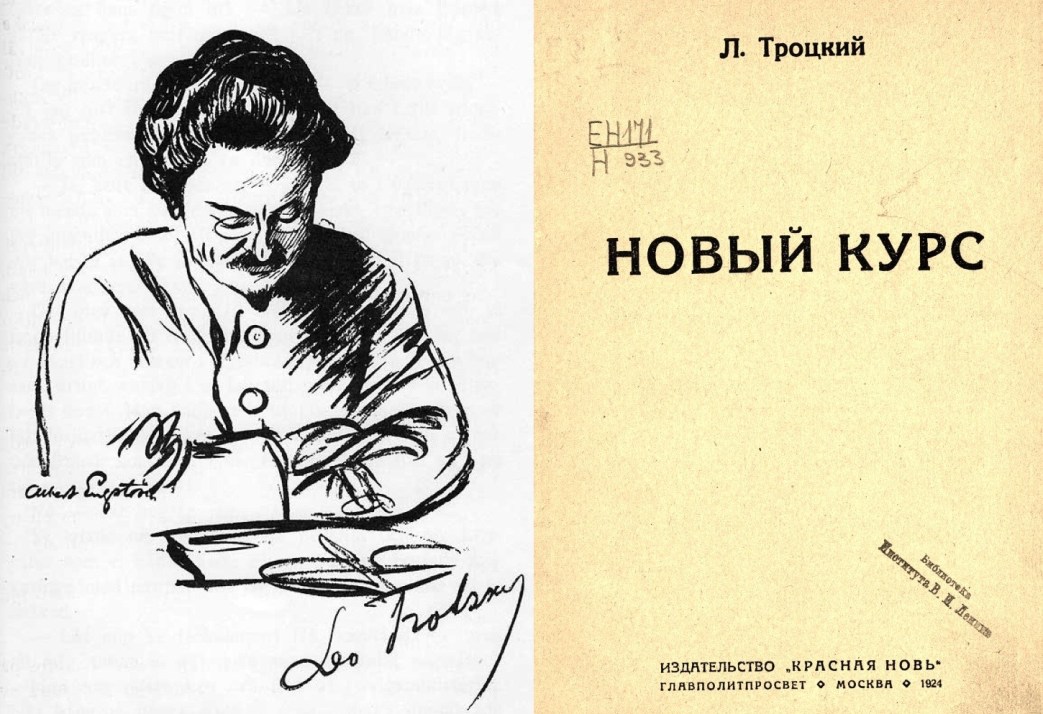

The ‘Left Opposition’ begins. The end of 1923 witnessed a definite retreat in the world class struggle as the post-war revolutionary wave receded. Germany saw its third (or fourth) failed revolution in as many years, Bulgaria saw a counter-revolution and the annihilation of its mass Communist Party, and Italian Fascism consolidated its rule over one of Europe’s most combative working classes. Internal to the Soviet Union, the New Economic Policy had brought some reprieve while at the same time bringing in to sharp focus the massive tasks ahead, and therefore disagreements on how to proceed. Any hope of Lenin’s recovery at the beginning of the year was dashed, with it clear he would not return to activity, aggravating existing divisions within the leadership. Almost immediately after the failed ‘German October’ an internal letter, the ‘Declaration of 46’, was sent to the Politburo by Trotsky and others. Ill with malaria, Trotsky was recovering in the Caucasus when he began a public series in December 1923 for Pravda, what is now known as ‘The New Course.’ Unable to attend the Central Committee Plenum that month, Trotsky addressed this letter presenting the ideas of the series, also printed publicly in the official press.

‘The New Policy’ by Leon Trotsky from International press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 12. February 15, 1924.

Letter addressed by Comrade Trotzky to the Session of the enlarged C.C. of the R.C.P. Moscow, 8th December, 1924.

Dear Comrades!

I had firmly hoped that I should be able to take part in the discussion on the inner situation and the new tasks of the Party, if not to-day, at least to-morrow. But my illness occurred, this time, at a most inconvenient moment and it has proved to be of a longer duration than the physicians had at first anticipated. I am, therefore, compelled to express my views by the present letter.

The resolution of the Political Bureau on the question of the Party Structure is of exceptional significance. It shows that the Party has arrived at an important turning point in its historical development. Such turning points, as has been pointed out quite justly in many meetings, require prudence; but in addition to prudence, firmness and resoluteness are also required. A waiting attitude, an irresolution at such a juncture, would be the worst form of imprudence.

Some comrades of a conservative disposition who show themselves inclined to over-estimate the role of the apparatus and to under-estimate the initiative of the Party, criticise the resolution of the Political Bureau. According to their statements, the C.C. takes upon itself obligations which cannot be carried out; the resolution would only create illusions and negative results.

It is clear, that this kind of view is inspired by a thorougly bureaucratic mistrust of the Party. The new policy proclaimed by resolution of the Central, denotes precisely, that the centre of gravity, which during the old policy had been erroneously inclined towards the apparatus, is now, during the new policy, to be inclined towards the activity, the critical initiative and the self-government of the Party, the organized vanguard of the proletariat. The new policy does not all mean that the apparatus of the Party is instructed to decree, to create or to establish the regime of democracy within a certain term. Nay, this regime can be created by the Party itself. The task is briefly the following: the Party must subordinate to itself its own apparatus, without ceasing even for a moment, to be a centrlized organisation.

In recent discussions and articles it was pointed out very frequently that the “pure”, the “entire”, the “ideal” democracy is unattainable, and that for us democracy in general is not an end in itself. This cannot be in any way disputed. But with the same right and with as much reason one can say, that pure or absolute centralism is unattainable and incompatible with the character of a mass party, and the centralism as well as the party apparatus are in no way ends in themselves. Democracy and Centralism are two faces of the party structure. The task is to equilibrate them in a proper manner, i.e. in that manner which best corresponds with the situation. In the past period, this equilibrium did not exist. The centre of gravity had been erroneously inclined towards the apparatus. The initiative of the Party had been reduced to a minimum. This involved methods and habits in the leadership which are diametrically opposed to the spirit of the revolutionary Party of the proletariat. The excessive centralization of the apparatus, at the expense of the initiative of the Party, has created within the Party the feeling of its insufficiency. On the extreme wings, it has assumed an extraordinary morbid form, right up to the formation of illegal groupments under the leadership of elements undoubtedly hostile to Communism. At the same time, within the Party, the critical attitude towards the mechanical methods adopted for the solution of questions, has party sed The Best threatens to last the patient, that the bureaucratism lead Party an impasse, has become almost general. Warning voices have been raised against this danger. The resolution on the new policy is the first official and extremely important form of expression of this turn within the Party. It will be carried out to the extent to which the Party, i.e. its four hundred thousand members, will be ready and able to do.

In a number of articles, it is obstinately sought to prove, that the fundamental means for reviving the Party, consists in raising the cultural level of its rank and file, whereupon the rest, i.e. the workers democracy, would grow of itself. It cannot be denied that we must raise the intellectual and cultural level of the Party with a view to the tasks which are confronting it; but precisely for this reason, this purely pedagogical method is insufficient and, consequently, false; and if we insist upon it, we cannot but provoke an aggravation of the crisis. The Party cannot otherwise raise its level as a Party than by completely carrying out its fundamental tasks by means of the collective leadership of the working class and with the initiative of all Party members–and of the proletarian state. We must deal with this question not with a pedagogic, but with a political method. The application of Party democracy must not be rendered dependent upon the degree of “schooling” of the Party members for Party democracy. Our Party is a Party. We have the right to be very strict towards everybody, who wants to enter our Party and to remain in it, but once anybody has become member, it is by this fact alone that he takes an active part in the entire Party work.

It is precisely by killing initiative, that bureaucratism hampers the raising of the general level of the Party. And in this consists its main fault. Since the Party apparatus is unavoidably constituted out of the most experienced and proved comrades, the worst consequences of the bureaucratism of the apparatus will be its influence on the ideological-political formation of the young generation of the Party. It is precisely owing to this circumstance that the youth–the surest barometer of the Party—reacts against the Party bureaucratism in the most energetic manner.

It would be a mistake, however, to believe, that the excess of mechanical solutions of Party questions should remain without influence on the old generation which embodies the political experience and the revolutionary traditions of the Party. Nay, the danger is also very great in this sphere. It is not necessary to speak of the immense authority of the older generation of our Party, not only within Russia, but also in the International: it is known and recognised everywhere. But it would be a crude error to estimate this authority as sufficient in itself. It is only by continual mutual influence of the younger and the older generation within the frame of Party democracy, that the old guard can be maintained as a revolutionary factor. Otherwise, the old ones would be easily become ossified and, without realizing it, become the most perfect expression of the bureaucratism of the apparatus.

A degeneration of the “old guard” is to be observed several times in the development of history. Let us take the most recent and most striking historical example: the leaders and the parties of the Second International. We know perfectly well that Wilhelm Liebknecht, Bebel, Singer, Victor Adler, Kautsky, Bernstein, Lafargue, Guesde and others have been direct and immediate disciples of Marx and Engels. We know, however, that all these leaders some partially, others totally have in the atmosphere of parliamentary reform and of the strong growth of the party and trade unions apparatus, degenerated towards opportunism. On the eve of the imperialist war, we saw with remarkable distinctness, how the formidable social democratic apparatus, protected by the authority of the old generation, became the most powerful hindrance to the revolutionary development. And we must say—we “the old ones”—that our generation which, of course plays the leading role in the Party, does not by itself conclude any guarantee sufficient in itself, against a gradual and imperceptible weakening of the proletarian and revolutionary spirit, if the Party tolerates the further development of the bureaucratic methods of the apparatus, which transform the young generation into a passive object of education, and unavoidably confirm the alienation between the apparatus and the mass, between the old and the young. Against this undoubted danger, there is no other means than a serious, profound and fundamental new orientation towards Party Democracy with a continually increasing attraction of the proletarians from the workshops to the Party.

I shall not go into full details on the juridical interpretations of Party Democracy and its limitations prescribed by the statute. No matter how important these questions are, they are but secondary questions. We shall examine them in the light of the experience at our disposal and shall modify that which can be modified. But, before all, it is the spirit prevailing in our organizations, which must be modified. The Party, through its nuclei and unions, must again acquire the collective initiative, the right for a free and comrade-like criticism without anxiety and fear, the right of organizatory self-government. The Party apparatus must be absolutely regenerated and renewed by means of compelling it to understand that it is the executive mechanism of the great collective body.

In the Party press, a great number of examples have recently been adduced characterizing the far-developed bureaucratic degeneration of Party practices and conditions. In response to critical voices, one met with the retort: “What is the date of your membership book?” Before the resolution of the C.C. regarding the new policy had been published, the bureaucratized representatives of the apparatus had considered all mention of the necessity of the modifying the inner Party policy as heresy, as formation of fractions and undermining of discipline. And now they are in the same way formally prepared to “take note” of the new policy, i.e. in practice to stow it away in a pigeon-hole. The renewal of the Party apparatus of course strictly within the frame of the Statute must have as its aim the substitution of the fossilized bureaucrats by fresh elements who are closely connected with the life of the whole Party or who are able to guarantee a suitable leadership. And before all there must be eliminated from the leading Party posts those elements who, at the first sign of criticism, of protestation or of objection, seek to silence it by demanding production of the membership book. The new policy must have as its first result, that all members of the apparatus from the bottom right up to the top, realize that nobody is allowed to terrorize the Party.

It is by no means sufficient for our Youth merely to repeat our formulas. It must make the revolutionary formulas their own by fight, fill them with life, it must form its proper opinion, its proper features and become capable of fighting for its views with the courage which is furnished by a profound conviction and an entire independence of character. We must rid the Party of that passive obedience which leads to doing everything with eyes mechanically fixed on the superiors; we must rid the Party of all spineless, servile and career-hunting elements. The Bolshevik is not only a disciplined man: no, he is a man who goes deeply into the matter and who, in every case, forms a well-founded opinion and courageously defends it in the struggle, not only against the enemies, but also within his own Party. Perhaps to-day he is in the minority in his organization. He subordinates himself, since it is his Party. But that does not, of course, always mean, that he is wrong. It is perhaps only, that he has perceived and understood earlier than others, the new task on the necessity of a change of policy. He will pertinaciously raise the question a second, a third and, if necessary, a tenth time. By so doing he will render a service to his Party, as he will help it to prepare itself for the new task, or to accomplish the necessary change without organic tremors and without fractionary convulsions.

Yes, our Party could not fulfil its historical mission, if it became decomposed into fraction groupings. This must not and will not be done. The Party as a whole, as an autonomous collectivity, will prevent this. But the Party will successfully combat the dangers of the formation of fractions only when developing, confirming and strengthening the new policy towards workers’ democracy. It is precisely the bureaucratism of the apparatus, which is one of the principal sources of fraction-formation. It suppresses criticism and enables discontent to penetrate the organization. It is inclined to label any individual or collective, critical or warning, voice as fractionism. Mechanical centralism is unavoidably complemented by fractionism, a caricature of democracy and a formidable political danger.

With a clear understanding of the entire situation, the Party will accomplish the necessary change with all the firmness and resoluteness which the importance of the tasks confronting us require. It is precisely by this means, that the Party will raise its revolutionary unity to a higher level as a guarantee for the successful accomplishment of the immensely important tasks, both in the political and in the economic sphere and on a national as well as on an international scale.

I am far from having exhausted the question. I have, intentionally, refrained from examining many of its essential aspects, in order not to occupy too much of your time. But I hope, that I shall soon succeed in getting rid of the malaria, which—in my opinion—is obviously in opposition to the new policy of the Party, and then I shall try to expound in free speech more precisely that which I have not expounded in this letter.

Fraternal greetings

Leon Trotzky.

Moscow, 10th December 1923.

P.S. I take advantage of the fact that my letter is published in the “Pravda” with a delay of two days, to make some supplementary remarks.

I understand that, when my letter was communicated to the ward meetings, certain comrades gave expression to the fear that my observations on the relations between the “old guard” and the young generation might be exploited for opposing the young to the old (!). It is obvious that such apprehensions would only confront those comrades, who, only two or three months ago, repudiated with horror the mere idea of bringing the question regarding the necessity of a change of policy up for discussion. In any event, the expression of similar apprehensions, at the present moment and in the present situation, can only be the result of a false valuation of the dangers and of their importance. The present state of mind of the Youth which, as is quite clear to every reflecting Party member, is largely symptomatic, has been precisely promoted by these methods employed for the sake of “absolute tranquility”, which are condemned by the resolution unanimously adopted by the Political Bureau. In other words, the “absolute tranquility” has itself promoted the danger of an increasing alienation between the leading Party stratum and the younger members of the Party, i.e. of its overwhelming majority. The tendency of the apparatus to think and to decide for the whole Party, is apt to lead to the authority of the leading circles becoming based solely upon tradition. The respect towards the tradition of the Party is undoubtedly a very necessary element of the Party education and cohesion; but it can be a vital and resistant factor only, if it is constantly nourished and strengthened by means of an independent and active control of the Party tradition, i.e. by the collective elaboration of the policy of the Party at the given moment. Without this activity and initiative, the respect towards the tradition might degenerate into a stage-managed of an independent and active control of the Party tradition, i.e. into a form without contents. It is quite obvious that such a kind of contact between the generations would be entirely insufficient und unreliable. It could retain a solid exterior, right up to the very moment at which the threatening rifts are revealed. Precisely in this lies the danger of a policy of the apparatus based on “absolute tranquility” within the Party. And, as far as those representatives of the older generation who have remained revolutionary and have not become bureaucratized (and this, as we are convinced, applies to the immense majority) will see quite clearly the perspectives characterized above, and, on the basis of the resolution of the Political Bureau, will do their utmost in order to aid the Party to carry out the resolution, just so far will the main possibility of opposing the various generations against on an other, disappear. It will then be relatively easy to overcome these or those “excesses” or exaggerations on the part of the Youth. But before all, it is necessary to create the safeguard against the concentration of the Party traditions in the apparatus, and thereby ensure its remaining vital and renewing itself in the daily practice of the Party. It is only by this, that also another danger can be avoided: that of splitting of the old generations into “apparatus-men” charged to maintain the “absolute tranquility”, and into those, who have nothing in common with that. It need not be said that the apparatus of the Party, i.e. its organizatory skeleton, will not be weakened, but strengthened by abandoning its aloofness. But there will be no doubt within our Party that we need a powerful centralized apparatus.

Perhaps it could still be objected, that the example of degeneration of Social Democracy through its apparatus in the reformist epoch, which I cited in my letter, is not appropriate in view of the profound difference between the epochs: the former stagnating reformist one, and the present revolutionary one. It is, of course, understood that an example is but an example and in no way an identification. However, the revolutionary character of our epoch is no guarantee in itself. It is not for nothing that we point out the dangers of the NEP, which are closely connected with the present moderate tempo of the international revolution. Our daily practical work in the administration of the state, which becomes continually more detailed and specialized, involves, as is emphasized in the resolution of the Political Bureau, the danger of a narrowing of the horizon, i.e. of opportunist degeneration. It is evident that these dangers become the more serious, the more a monopoly of authority in the hands of secretaries tends to substitute the Party leadership. We should be bad revolutionaries, if we were to rely upon the “revolutionary character of the epoch”, to help us in overcoming all difficulties, in particular all the inner difficulties. It is the “epoch” which must be helped in a proper manner, by a rational carrying out of the new Party policy proclaimed unanimously by the Political Bureau of the C. C.

A further remark in conclusion. Two or three months ago, when the questions forming the object of the present discussion, were only beginning to engage the attention of the Party, some responsible comrades of the provinces were inclined to treat the matter in an off-hand manner; it was, they declared, merely a brain wave on the part of Moscow, in the provinces, however, everything was at its best.

And now also we observe this attitude of mind in one or the other reports from the provinces: infected or excited Moscow is opposed to the “quiet and reasonable province”. This means nothing else than a violent expression of the same bureaucratism, though in a provincial edition. As a matter of fact, the Moscow organization of our Party is the largest, most vital and the best equipped with forces. Even in the moments of the greatest stagnation, the activity and the initiative of the Moscow organization were, in spite of everything, more intensive than anywhere else. If Moscow at present differs from other localities over something, it is only due to the fact, that it has taken the initiative for the revision of the policy of our Party. This is not a defect, but a merit. The whole Party will follow Moscow in passing through the necessary period of the transvaluation of certain values of the past period. The less the provincial Party apparatus opposes itself to this, the more systematically the provincial organizations will win through the unavoidable period of criticism and self-criticism. The Party will garner the result in the form of an increased inner firmness and a raising of the level of the Party culture. L.T.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n12-feb-15-1924-inprecor.pdf