Full text of leading C.P. unionist William F. Dunne’s pamphlet on the 1926 British General Strike, to which he was a witness.

‘The British Strike: Its Background, Its Lessons’ by William F. Dunne. Daily Worker Publishing, Chicago. 1926.

INTRODUCTION.

The recent general strike of the British Trade Unions must be studied carefully by American workers, for in the nine days during which industry in Great Britain was stopped, there occurred the greatest demonstration of working-class power seen since the Russian revolution.

In a number of ways the British strike furnishes object lessons for the American labor movement more clearly applicable to the struggle here than does the Russian revolution.

First, the British general strike occurred in a country highly industrialized, possessing a powerful and disciplined trade union movement.

Second, the general strike developed out of a wage struggle—the British capitalists, backed by the British government were trying to reduce the wages of the miners as the first move in an attack on the living standards of the whole British working class.

Third, Britain is one of the countries which were “victorious” in the world war and the general strike is the first great upheaval to take place in a country which “won.”

Fourth, the American trade union movement has been patterned largely after the British trade union structure and is dominated by the same craft union and separatist fetishes which once prevailed in Britain.

Fifth, Great Britain, like the United States, is one of the “democratic” countries, with the best established parliamentary system in the world.

Sixth, Great Britain is the classic example of an imperialist nation, holding under its rule more colonial workers and peasants than any three other nations combined.

Seventh, Great Britain and the United States are the two great rivals for the economic, financial and military domination of the world. The commercial struggle between these two imperialist powers will end inevitably in a bloody world war unless the British and American working-class are well-organized and conscious enough to stop it.

Eighth, the magnificent courage and solidarity of the trade union membership, the unemployed and even the unorganized workers of Great Britain in support of the coal miners and the general strike, are in striking contrast to the hesitancy and weakness of the Trades Congress officials who because of their unwillingness to face the fact that the British government was the real enemy of the labor movement, entered into a secret agreement with it, deserted the coal miners and brought about a defeat of the labor movement for which they are solely responsible.

Ninth, the existence of an organized left wing—The National Minority Movement—its part in rallying the labor movement to the support of the miners.

The Struggle in Britain.

The coal miners of England, Scotland and Wales are fighting against the attempt of the coal owners and the government to reduce their wages, lengthen their hours and break up their union.

The entire trade union movement of Great Britain, convinced that the attack on the miners was an attack on the whole working class, knowing that the defeat of the miners would he the signal for an onslaught on the rest of the trade unions, came to the assistance of the miners in one of the most striking (the pun is excusable) demonstrations of solidarity in labor history.

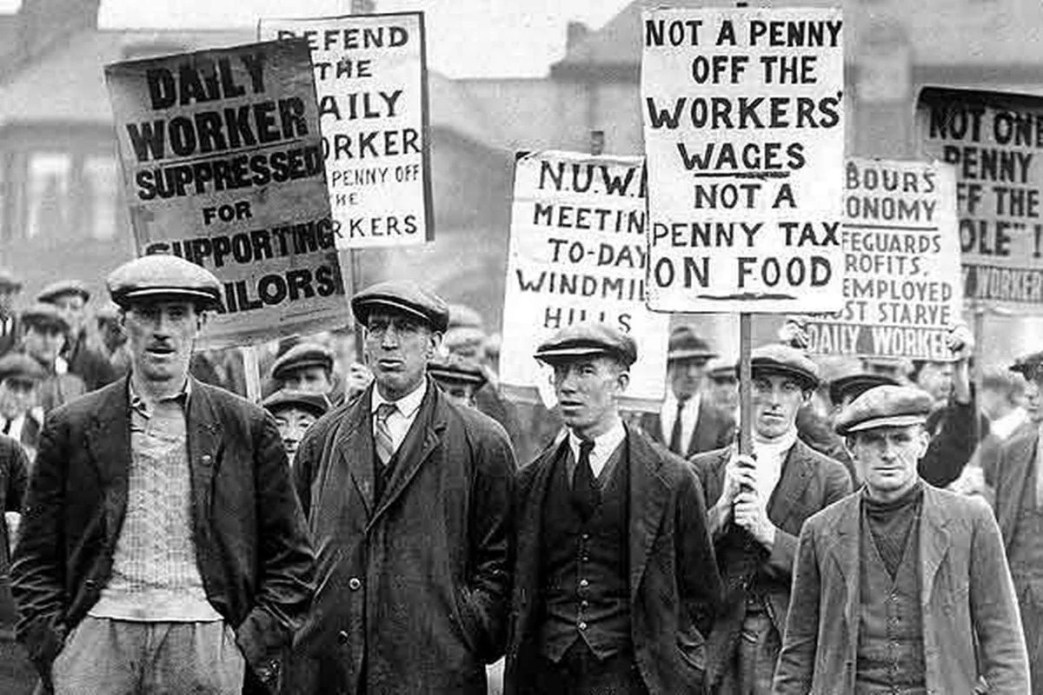

The real meaning of the recent struggle (by no means ended by the calling off of the general strike) was that the British labor movement said to the British lords of industry and finance and to their instrument, the British government:

“Not one penny off from wages or one minute added to the hours of labor.”

Great Britain has not been able to regain her premier world position in finance and trade she enjoyed before the war. Industry declines steadily, the hankers of Wall Street have superseded “the old Lady of Threadneedle Street,” and unemployment in England is of a mass character.

British capitalism can survive only by lowering the standard of living, while at the same time forcing more production from the workers. In such a situation labor’s slogan of no wage reductions and no Increases in hours is actually a challenge to the British ruling class.

The wage struggle in Great Britain has become a revolutionary struggle.

For months the capitalist press of the world had been placing its confidence in the right-wing leadership of the British trade unions as the bulwark between the mine owners, the government and the masses of the trade union membership.

But MacDonald, Henderson, Clynes and Thomas were forced for a time to support both the miners’ strike and the general strike and the capitalist press stood aghast.

For was this not Britain, the cradle of capitalist democracy and parliamentarism, where the sole important survivor of European royalty still lives and thrives in Buckingham on the bounty of the bourgeoisie?

All signs fail in dry weather, says an old proverb and the prophets of the capitalist press have been unable to understand that just as British diplomacy was the most successful in the world when British finance ruled the world markets but meets humiliating defeats in the present period (consult Austen Chamberlain) so does the influence of reformist trade union leaders wane in a country of declining capitalism.

And British capitalism is on the decline. The British workers feel this in the lowered standard of living and chronic mass unemployment though comparatively few may thus describe the basic reason for the present struggle.

The pressure from below as a result of the downward tendency of wages and working conditions, coupled with the arrogant attitude of the employers and the government, has forced into line with the demands of the masses for action many trade union and labor party officials who in other circumstances have been able to excuse their unwillingness to lead the labor movement m a militant struggle.

But so rapidly has the crisis developed, so swift has been the response of the trade union membership to the offensive of the government, so overwhelming has been the proof furnished the workers that weakness and hesitation mean the destruction of the British labor movement, that a labor leader who attempts to repeat the treachery of Prank Hodges in wrecking the triple alliance m the last great crisis, will be driven from the labor movement. Not tomorrow, or the next day perhaps but very soon as history measures, such periods.

The British trade unions have made the first and most necessary step in bringing their policy and tactics into line with the basic fact of British capitalism—its decay. The general strike of the British trade unions means the beginning of the open struggle of the British proletariat for power: the solving of a whole series of new problems.

Rapid Development of Crisis.

THE rapidity of the development toward the present’ crisis in British industrial and political life can be gauged best by the fact that less than one month before the general strike occurred the best informed labor men in Great Britain and on the continent believed that no strike of coal miners would take place.

Early in April a conference was held in Paris attended by influential British trade union officials, spokesmen of the continental labor unions and by high officials of the All-Russian trade unions. The conference was called to consider the miners’ situation. After thorough consideration of all factors—mine owners, the miners’ union and the British Trade Union Congress and the government—it was the unanimous opinion of the delegates that no strike would occur.

This opinion has additional significance if it is remembered that every person at the conference was opposed to the report of the coal commission, and believed that the campaign to lower wages and lengthen hours must be met by a counter-offensive on the part of labor and that each had done much to put the British labor movement in fighting trim in preparation for just such a situation.

In addition to the opinion that no strike of coal miners would occur there was the further belief that if it did it would receive only half-hearted support from the rest of the labor movement.

For obvious reasons I cannot give the names of the labor men who were at this conference but they are those men in closest touch with the masses and who follow closely every phase of the British movement. Yet the miners struck, the Trades Union Congress supported them. British industry was paralyzed and the government and the capitalist press talked hysterically of revolution.

The speed and momentum of mass movements are hard to estimate and in Great Britain this is doubly true.

So well established is the belief in the British devotion to parliamentary methods, so many times has the labor party parliamentary leadership succeeded by diverting strike action into channels where the militancy of the masses has been dissipated, so involved with the aims of British capitalism is an influential section of the trade union leadership, so strong was the belief that the subsidy to the coal owners would be continued—temporarily, at least—that those who worked the hardest for and wanted most the awakening of the British labor movement to its danger and the need for unity and struggle, despaired of anything like united action at this time.

The Situation Preceding the Strike.

The National Union of Railwaymen, headed by J.H. Thomas, leading figure In the Labor Party and former member of the Privy Council, an imperialist to the backbone, had signed a (new agreement with the employers and this was looked upon as definite indication that the union would take little or no part In any general struggle of the rest of the trade union movement.

The Amalgamated Engineering Union (engineers in Great Britain are machinists, etc.) began negotiations for a new agreement and met with unexpected opposition from the bosses who insisted on district agreements, lower wages and a change for the worse in the job conditions. One of the most powerful unions in Great Britain, it was evident that the capitalists believed that the A.E.U. would not fight and that if it did it would receive but little support from the rest of the labor movement.

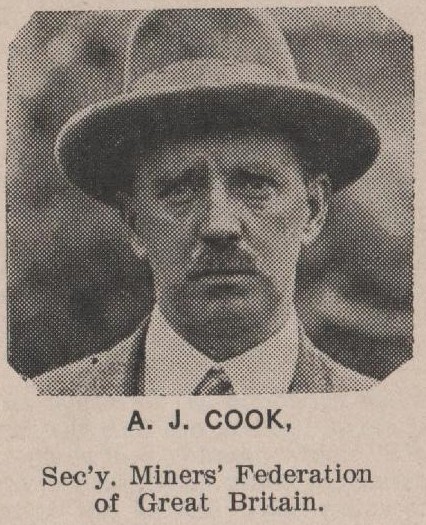

Undoubtedly the metal trades bosses found comfort in the fact that a majority of the executive board of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain was opposed to the militant policy of A.J. Cook, its secretary, whom the capitalist press always calls a Communist but who is not a member of the Communist Party.

They depended also upon Thomas to prevent the Railwaymen’s Union tying up transport in the event of a Trades Union Congress decision to support the miners.

However, things began to happen in the coal fields, which exerted tremendous influence in shaping the policy of the Trades Union Congress.

A.J. Cook, secretary of the Miners* Federation of Great Britain, is an honest and militant official. He was elected because he supported the program of the left wing in the union for nationalization of the mines and a national minimum wage. Cook had confidence in the rank and file. He felt that they were fed up with unkept promises and were prepared to fight the basic program of the Coal Commission report of wage reductions, increases in hours and the break-up of the miners’ union thru a system of district agreements. He was sure, moreover, that the miners understood that back of the mine owners and the coal commission stood the British government and that they should also understand that in rejecting the commission report and deciding for strike action they must engage in an open struggle with the state power.

Officials War on Left Wing.

The official leadership of the labor party was more concerned with ejecting the Communists and warring on the left wing than with the troubles of the miners.

Nationalization of the mines, a minimum wage based on the cost of living for the miners, had been allowed to become mere academic issues. The coal commission’s report was attacked more by this group because it urged the end of the subsidy to the mine owners than because it threatened the living standards of the miners.

The whole leading group of the Communist Party with a few exceptions, had been sent to Wandsworth prison for telling soldiers and sailors not to shoot workers when called upon to do so, and this had occurred as a direct result of the offensive against the Communists, launched by the MacDonald wing of the Labor Party at Liverpool.

The strike of the seamen earlier in the year had been lost because the official labor movement did not support it.

The only encouraging signs were the victories of a number of labor party candidates in by-elections but these victories had served mostly to strengthen the confidence of the officialdom in the effectiveness of pure parliamentary action.

Rise of the Left Wing.

Cook began a tour of the coal fields.

The Labor Party officialdom looked on at first contemptuously, then tolerantly and then with amazement.

The meetings of miners listened to Cook and then voted for the left-wing program unanimously or by majorities so huge that no one could be in doubt as to their sentiments.

Durham district, the stronghold of Herbert Smith, chairman of the Miners’ Federation and leader of the opposition to Cook in the executive committee, endorsed the program of the left wing. So did South Wales, Lanarkshire, Scotland, and other decisive districts.

The executive committee responded to the unmistakable demand and, following the instructions contained in the resolutions passed at mass meetings and delegate meetings, asked for full support from the Trades Union Congress.

The Miners’ Federation is the largest union in the Trades Union Congress and when it spoke with one voice thru its executive, a voice which the T,U.C. officials knew was the voice of over a million miners, whose votes had been recorded daily in the London Herald, official organ of the T.U.C. and the Labor Party (an organ, by the way, whose chief support comes from the miners), it was listened to with a new sympathy and respect.

In the meantime, in the whole labor movement, a new militancy could be noticed. The left wing was consolidating its influence and it had issues and a program which began to group around its center—the National Minority Movement—the best elements of the trade union movement.

The attack on the living standards of the British workers, particularly those in decisive industries, like coal mining and metal, coupled with the apathy of the official labor party and trade union leadership, formed the basis for a left-wing movement whose rapid rise to a position of influence is one of the outstanding features of the British situation.

Work and Program of the Minority Movement.

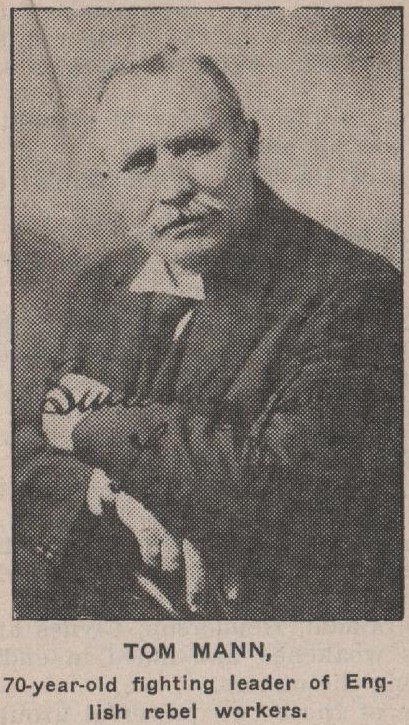

At the head of the Minority Movement is Harry Pollitt, member of the Boilermakers’ Union and also a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, now in Wandsworth prison following his conviction on a charge of “fomenting mutiny in the armed forces of the crown” brought under (an act passed in 1704. Nat Watkins of the South Wales Miners’ Federation and George Hardy, well-known member of the I.W.W. who served a sentence In Leavenworth for anti-war activities and was then deported from the United States, are now in charge of the work of the national office of the Minority Movement. The British capitalist class has a legitimate grievance against our rulers for sending Hardy back home. Active on the executive are such well-known fighters as Tom Quelch and Tom Mann.

The aim of the Minority Movement was and is to give to the trade unions a militant program, to build them into real weapons of the British masses. Practical work to this end is the chief feature of the movement.

Nat Watkins, for instance, went into the Forest of Dean mining district with A. Purcell, since he was elected to parliament from the constituency, and conducted what the British movement calls an “All In Campaign,” i.e., an organization drive which brought the percentage of union organization from 30 per cent up to 90 per cent.

In the recent stride of seamen the Minority Movement actually had the leadership in the person of George Hardy.

Hundreds of minor trade union officials—branch secretaries, local organizers, etc.—are members of the Minority Movement and together with the rank and file militants are doing much of the routine work by which a trade union movement is built.

The program of the Minority Movement for support of the coal miners was simple. It was:

1. Rejection of the coal commission’s report on nationalization.

2. All unions behind the miners.

3. A national council of action with corresponding local bodies in every industrial district.

At the first National Minority conference held in Battersea last fall, some 600,000 workers were represented.

At the special conference held last March 950,000 workers were represented. In other words about 20 per cent of the British trade union membership were actively supporting the program of the National Minority Movement.

Distinct from the Minority Movement is the still broader left wing personified by such men as Wheatley, Maxton, Hicks, Bromley, Williams and other trade union officials and labor members of parliament influenced by strong left pressure from their followers and who have followed a policy more to the left than that of MacDonald, Henderson, Clynes and Thomas, but who nevertheless weakened and aided in ending the general strike and deserting the miners.

The pressure of these two powerful groups upon the executive of the miners in support of A.J. Cook brought the leading committee of the Miners’ Federation into line.

The immediate policy as formulated by the Miners’ National Minority Movement in a conference held March 22, was as follows:

We call upon the miners to concentrate upon securing 100 per cent organization and to prepare to fight for the guaranteed weekly minimum wage commensurate with the increased cost of living whilst recognizing that the necessary reorganization, so as to permit this, is only possible by the nationalization of the mining industry without compensation and with workers control.

We have seen how the miners rallied behind Cook and came to the Trades Union Congress General Council prepared for struggle.

In the other unions similar campaigns for support of the miners carried on with the slogan that, “the attack on the miners is an attack on the whole trade union movement.”

How well the Minority Movement did its work is shown by the general strike in support of the miners, which astounded and frightened the capitalist world.

The capitalists’ press is loud in its protests against the challenge to parliament and the use of such drastic measures m a wage struggle. The British strike for a wage struggle true enuf but its implications are far wider than the immediate causes which produced it.

The Jailing of Communists and the Result.

The Communist Party of Great Britain told the workers last summer in their press and at meetings that the government was prepared to smash the trade unions. They said also that a campaign against the use of the military as a strikebreaking agency was necessary and that the struggle of the miners would inevitably involve the whole labor movement

The party issued its now famous “Don’t Shoot! leaflet to the soldiers and sailors and twelve members of the central executive committee were sent to prison under the Mutiny Act of 1797

No sooner were they convicted than a nation-wide campaign for their release began. The rank and file of the trade unions were aroused and even the right-wing leadership had to go along with the tide.

Sir William Joynson-Hicks, the home secretary in the Baldwin government, derisively called “Jix” by the workers, succeeded in raising a storm of protest against himself the right wing of the labor party and of the trade unions tried hard to show that the jailing of the Communists was a personal enterprise, of an egotistical reactionary, but the rapid development of the coal crisis, the organization by the government of the O.M.S. with fascist participation, were indications that the drive on the Communists was no isolated incident.

The prosecution and imprisonment of the leading staff of the Communist Party can be said without exaggeration to mark a new period in the development of the British labor movement.

It dramatized sharply the decadence of the boasted British democracy because it showed clearly to thousands of workers that under the Tory regime sedition unaccompanied by any overt act had become a punishable act in time of peace.

It is my opinion that even considerable numbers of Communists were surprised at the drastic measures used against them.

The response of the masses to appeals for the defense of and financial aid to the dependents of the imprisoned Communists was splendid. International Class War Prisoners’ Aid reached hundreds of thousands of workers by mass meetings, demonstrations and literature.

The treatment of the prisoners, their imprisonment as common criminals with no distinction because of the political nature of their offense became topics of wide discussion in the capitalist as well as in the labor press.

On April 12 a parade, mass meeting and demonstration was held in London in honor of the six Communists who were released after serving their sentences. (Arthur McManus was held three days longer because he had “insulted” a warder.)

Ten thousand workers gathered at King’s Cross Circus and marched the four or five miles to Clapham Common. Half of them had already walked from five to fifteen miles to reach King’s Cross.

Twenty thousand people took part in the meeting at Clapham Common where speakers of all shades of political opinion addressed the huge crowd from a dozen platforms.

Then the crowd marched three miles more to Wandsworth Prison, where another meeting was held, while 20,000 workers following the lead of a chairman in the most disciplined fashion, made the walls of the prison shake with thunderous shouting for more than two hours.

I have never seen a hoarser or happier crowd.

The direct attack on the Communist Party as a preliminary to the attack on all of organized labor, the complete correctness of the slogans and program of the party Increased its influence tremendously. The general strike and the massing of the military by orders of the government actuated by an obviously deadly purpose has shown the masses that the jailing of the Communists was the signal for the offensive of British capital.

The slogan issued by the Communists to the soldiers and sailors has taken on life. “Don’t Shoot!” is now a mass appeal of workers in industry to workers under arms.

On May Day the United Press correspondent in London cabled as follows about the May Day parade:

“Conservatives and Laborites alike were dumbfounded by the discovery that the sharp rocks of the day’s developments had changed the status of the Communists in London. Today…the reds from Battersea proudly led off the procession. They simply took the lead, none said them nay and there they marched in place of the usually acknowledged leaders.

Not actually but with a relentless potentiality the social revolution marched with the London workers on May 1.

The New Outlook of British Labor.

The British working class has been given an entirely new set of standards by the general strike. They look at Britain and its empire with new understanding.

When the Trades Union Congress meeting at Scarborough passed its famous resolution upholding the right of all colonial peoples to separate themselves from the empire, cold shudders ran down the spines of British imperialists.

Their cold chills vanished however when the Liverpool conference of the Labor Party under the pressure of the MacDonald and Thomas wing decided to exclude the Communists whose activities had of course been in support of the antiimperialist resolution.

The whole trade union movement has seen now the army and navy, those noble instruments whose heroic deeds in defense of the empire have been recounted in song and story, mobilized land placed on a war footing for an assault upon the working class of Britain.

The cold truth is, and every British worker knows it now, that the armed forces of Great Britain are being used against the trade unions of Great Britain in exactly the same manner that they have been and are being used against the rebellious workers and peasants of India, Egypt, Ireland and China. There is at present a difference of degree but not in kind.

The British workers, with troops in “tin hats,” armored cars and tanks parading the streets of the industrial centers, know now by what they see with their own eyes, that British imperialism is their enemy.

Much sooner perhaps than even the sponsors of the Scarborough resolution believed, that resolution has been given life by the relentless process of decay within the structure of British imperialism.

The imperialist rulers of Great Britain are preparing another Amritsar, but this time the scene is shifted from India to England and fair-haired British workers, not swarthy Hindu peasants, are to be the victims.

In the West End clubs, according to W.N. Ewer, foreign editor of the Daily Herald, there was open talk of “machine gunning” during the general strike and an open lust for slaughter hitherto expressed only towards the “backward races.”

The interests of the two classes in Great Britain now run directly counter to one another—the ruling class must struggle to maintain the empire, the working class moves in a direction opposed to the whole idea of empire.

The weakness of the national liberation movements which have disturbed the even tenor of empire progress since the war, and since the Russian revolution by liberating the oppressed peoples from the czarist yoke gave la glorious example to the colonial masses of the whole world, has been that the British working class, bound by reactionary and reformist leaders to the imperialist chariot, was able to give them little assistance.

The general strike has broken with one stroke the connection between the British masses and their imperialist rulers. Never again will a colonial war be fought by other than mercenary legions and then only in the face of stern resistance from the trade unions.

And in its struggles against the imperialist forays of the British rulers, the workers of Britain will continue to have the support of the allies who have rallied to them in the general strike—the industrial workers of both the colonial nations and the capitalist countries of Europe. A unity of action and purpose in the ranks of international labor has been established that will never be broken, for the British trade unions with one gesture as powerful as it is magnificent, have shattered the myth carefully maintained till now by the ruling class, the myth that British labor and British imperialism were one indivisible whole. The inevitable consequences for British imperialism can be understood only if we look carefully at the structure of the British empire and the conflicts in process of development within it and against it.

The Empire and British Labor.

The whole foreign policy of British imperialism is built around the protection of the route to India—the richest colony possessed by any power.

Not only has the general strike seriously damaged the prestige of Great Britain among the capitalist nations like Spain, France and Italy, who are in a position to threaten the key positions on the Mediterranean route, but the colonial peoples have had now, in the emphatic form of the general strike, proof that in their struggle against British imperialism, and the small imperialisms which operate within its circle of steel, they can count upon the aid of the most powerful ally of all—the British working class.

A glance at the water route to India on any map will make clear the strenuous efforts needed to maintain control of the strategic positions.

Only on a working class willing to fight and slave for the idea of empire can British imperialism base its strategy and maneuvers for the maintenance of an unobstructed route to India and without India Britain is no longer an empire.

For when it loses control of the road to India it loses likewise the entry to and the shortest approach to its African possessions.

Let us examine in some detail the elaborate structure—military and political—to build which the British ruling class has lavished its best diplomatic talent, untold wealth and the lives of thousands of workers.

The entrance to the Mediterranean is thru the straits of Gibraltar, on Spanish territory.

Across on the African side French and Spanish armies are struggling to conquer the stubborn and courageous Riffian tribesmen. Modern guns on the African side could easily silence the fire of Gibraltar and Great Britain, one can believe is watching very carefully the Franco-Spanish campaign in the Riff.

The island of Malta, the second link in the chain of British bases, lies close to the Italian coast. Its population is Italian and the imperialistic ambitions of Mussolini, anxious to expand Italian power in Africa, have not overlooked the desirability of Malta as an Italian instead of British naval base.

The third link in the chain is the Island of Cyprus—belonging to Greece. One of the chief reasons for British backing of the Greeks against Turkey in their recent disastrous war should now be clear.

The British navy in the Mediterranean is based on Gibraltar, Malta and Cyprus—and all of them are vulnerable to attack from neighboring nations.

The Suez Canal is in Egypt—a colonial nation, a Mohammedan nation, held in subjection by British troops and the British navy.

The troops and navy will keep Egypt in subjection only as long as the workers in the British Isles support the imperialist campaigns of their rulers.

The general strike was a greater blow to British prestige and British strength in Egypt than the loss of half of the British navy.

We can look for a new upsurge of the national liberation movement in Egypt very soon, accompanied by support from the British labor movement, not alone in sympathetic resolutions, but in deeds.

There is another route to India from the east and it Is important not only for India but for Britain’s power in China.

Upon this matter British labor has already spoken by opposing the building of the Singapore naval base, and the general strike, speeding up its drive to the left, will bring new complications for British imperialism to worry over.

The Right-Wing Leaders’ Cowardice.

London, May 4 —Shortly before midnight last night, J.H. Thomas, his face trembling, tears streaming down his cheeks, staggered out of the House of Commons, crying, “It’s all off. The strike is on. I’m going home—broken.”—News dispatch.

AS plain as the fact of the great British strike itself is the further fact that the British government openly and deliberately took upon itself the task of the mine owners and the rest of the capitalist class.

One needs only to read the dispatches to such newspapers as the New York Times which frankly champions the cause of the capitalists as against the workers to understand that the British government functioned during the general strike as what Engels called “special bodies of armed men,” to know that British capitalism concentrated all its forces of oppression into one apparatus and that apparatus is the regular and special police forces and the army and navy.

THE declarations of such men as J.H. Thomas, member of the Privy Council during the war, MacDonald, who while Labor Party premier sanctioned the use of methods against the workers and peasants of India Which were more brutal than those of Baldwin, Henderson, Clynes and the rest of the right wing leadership, to the effect that “the strike is not an attack on the constitution,” their complaint that the government was exceeding its authority, their efforts to give no offense to the bloody imperialists of which the personnel of the British government is composed but to outdo them in patriotism instead of telling the workers that the wage struggle must take on a political character If victory was to be secured, simply aided the government in its strategy.

THIS strategy was to force the issue of capitalist government versus the trade unions—to appear as the champion of the interests of the majority of the British people against the onslaughts of a minority.

Such a strategy can be met and counteracted only by a resolute, conscious knowledge of the implications of the struggle, a leadership which is using all its energy to rally and solidify the workers’ ranks for the overthrow of capitalism and the establishment of a workers’ and farmers’ government.

THE right wing leaders of the British Labor Party and the Trade Union Congress are just as much afraid of the workers as are the capitalists. They had a common meeting ground before the strike was called.

Not once during the strike did it appear in any of the dispatches that the reformist leaders made any attempt to capitalize for the extension and broadening of the strike the flooding of Britain with troops, the occupation in the best military and naval style of industrial sections and ports, the special legislation enacted, the suspension of all ordinary liberties and privileges, the open threat and the obvious preparation to crush the labor unions by military force.

WHAT part of these preparations were is told in extracts from dispatches culled from the Chicago and New York capitalist press published in connection with this pamphlet.

The evidence of correspondents who chronicled approvingly the events here set forth shows that the British government declared war on the trade unions and the working-class the moment the strike was called.

The government placed the army and navy on a war footing, it organized special auxiliary war services and after the passage of the emergency act—itself a war measure—it issued instructions to the military forces which legalized any steps they might care to take from the arrest of strikers to mass murder.

SELDOM has the leadership of a great trade union movement had such an opportunity as was given the right-wing leaders of British labor. “Given” is the proper word because the general strike was opposed by them.

But to MacDonald and Thomas this opportunity was no glorious chance to deal a deathblow to British imperialism but a reason for sorrow and tears. Weak and cowardly, this section of the labor leadership was weeping when the strike was called and when it ended.

No Confidence in Workers.

Not even the splendid array of stern-willed workers behind them could give them courage. They have the viewpoint of the ruling class, they are obsessed with the idea of empire and they could only wail of the losses to “England” caused by the strike. For them England is not the England of the tolling miners, metal workers, railwaymen, dockworkers and seamen, but the England of the middle class subservient as always to the traditions of the past even though it is no longer the bearer of those traditions.

The correspondent of the New York Times, reporting Thomas’ speech at Hammersmith while the strike was on, describes him and his type with rare accuracy as “a Conservative trying to please the Moderates without infuriating the Extremists.”

We quote from this speech:

“If the people who talk about a fight to a finish carried it out in that sense the country would not be worth having at the end of it. I have never disguised and I do not disguise now that I have never been in favor of the principle of the general strike. No one will disagree, however, that the fundamental principle of trade unionism is not only the right for men and women to organize but the essential part of that legal right is collective bargaining. The workers have no right to say to the employers: “YOU MUST NEGOTIATE UNDER THE THREAT OF A STRIKE,” but it is equally right and just that the workers should not be asked to carry on negotiations under the threat of a lockout.

“From the start I DELIBERATELY WENT IN TO GET PEACE. Let there be no mistake about that and in spite of all that has been said, I repeat that it is the duty of both sides to keep the door open.”

MacDonald vied with Thomas in truckling to the government.

On May 5 he rose in the House of Commons and said: “I again ask this house if it cannot do it. (Resume negotiations). I am not speaking for the Trades Union Congress at all. I am speaking for nobody. I have not consulted my colleagues. I am speaking from my own heart. I am not a member of a Trade Union, and am therefore a little freer than my colleagues, and can do things for which perhaps I will get blamed tomorrow by the trade unionists, but I cannot let this opportunity go.”

MacDonald may have been speaking “from my own heart” as he said, but it is plain that it is a heart filled with black treachery towards the trade union movement and the working-class.

PLAINLY put, right during the height of the strike, Thomas and MacDonald were trying to “get peace” at any price and while the government was deploying its troops into strategic positions and occupying working-class districts, they were doing their best to destroy the morale of the strikers.

Unity in the face of the enemy, whoever he is and wherever he appears, is the first principle of struggle whether it be open war or some small dispute. The bringing of ever-greater pressure to bear on the enemy, to throw into the struggle ever-larger forces, to demoralize the forces of the enemy, to strike Where he least expects it, all these are elementary rules of military operation.

WHY did not the leadership of the Trades Union Congress and the Labor Party appeal to the colonial workers and peasants m India, Africa and Egypt to support the strike of the British workers?

Why did they not say to them:

“This is your opportunity to strike a blow for your freedom.”

Because the reformist leaders would rather see the strike lost than won by methods which would see the workers on the road to power, because they think of England, capitalist England, first, and the working class last.

The British capitalists consider themselves the guardians of England and the empire and rightly so, they own them.

But for the leaders of workers to adopt this viewpoint is simply to deliver the workers under their influence to the ruling class in every crisis.

Capitalist Unity.

THE British rulers may and undoubtedly did differ on the tactics to be used in fighting the workers, but on the main question—who should rule in England—they were a unit.

State, church and press were solid against the strike. And here we make the connection between the right-wing leaders of the Thomas type and the blackest reactionaries who backed the government.

What essential difference is there between the Thomas statement that “the workers have no right to say to the employers that you must negotiate under the threat of a strike ” and the following statement of Cardinal Bourne made at high mass in Westminster Cathedral:

“1. There is no moral justification for a general strike of this character. It is a direct challenge to lawfully constituted authority and inflicts without adequate reason immense discomfort and injury on millions of our fellow countrymen. It is, therefore, totally against the obedience which we owe God, who is the source of that authority, and against the charity and brotherly love which are due to our brethren.

“2. All are bound to uphold the government and to assist the government which is the lawfully constituted authority of the country and represents, therefore, in its own appointed sphere the authority of God himself.”

CARDINAL BOURNE upholds the government, Thomas and MacDonald will not fight against the government. Both are enemies of the working class which find the government blocking its way both to a decent living standard and to power.

The most important lesson of the general strike for British labor and for labor in every land except the Soviet Union where they learned this lesson nine years ago and have never forgotten it, is that capitalist government is the concentrated force of the capitalist class and that trade union leaders and leaders of working class political parties who have not learned this lesson or, having learned it will not act in accord with it, must be deprived of power in the labor movement and driven back into the ranks of the open enemies of labor where they belong and in whose interests they function.

“War Preparations Against British Strikers Recorded by U.S. Capitalist Press.”

Premier Baldwin rose…and amid a stillness that was startling in comparison to the hubbub which had gone before said: “I have a message from the king, signed with his own hand.” This message proved to be the proclamation declaring the country to be confronted with a national emergency. Baldwin read the message and then moved that the commons reply to His Majesty that an emergency does in fact exist.

The declaration of an emergency carries with it the imposition of the death penalty for refusal of duty in the armed forces of the crown.

Guarantees are given that all persons continue or resume their work in faithful duty to the country will be protected hereafter from the reprisals or victimized by the trade unions, and the government will take all necessary steps to secure this.

His Majesty’s government will take effectual measures to prevent victimization by the trade unions of any man who remains at work or who may return to work, and no settlement will be agreed to by the government which does not provide for a lasting period and for its enforcement, if necessary, by penalties.

No man who does his duty by his government will be left unprotected by the state against subsequent reprisals.

A signed statement from Premier Baldwin appeared in the British Gazette reading as follows:

“Constitutional government is being attacked! Let all good citizens whose livelihood and labor has thus been put in peril bear with fortitude and patience that with which they have suddenly been confronted.

“Stand behind the government, which is doing its part, confident that you will co-operate in the measures undertaken to preserve the liberties and privileges of the peoples of these islands.

“The general strike is a challenge to Parliament and road to anarchy and ruin.”

***

Many charges were made by the police. . . and 72 arrests brought the total in Glasgow since Thursday night to more than 200.

In the southern area…sixty arrests were made…A number of rioters were brought before the sheriff’s court and sentenced to three months” hard labor in the majority of cases.

***

Noah Ablett, representing South Wales on the Miners’ Federation executive, was arraigned in police court today on charges of making a speech in Battersea, “which was liable to lead to disaffection among the civil population and the troops.”

***

Warrants have been issued for the arrest of all the leading members of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

***

The government is taking steps to prohibit the withdrawal of funds from banks for the aid of the strike without official sanction. It is believed that this is the first move to prevent the Trades Congress receiving financial aid from the unions in other countries.

***

The government is intensely proud of its military measures against the strikers. It feels that its “great convoy” of provisions along the main London thoroughfares yesterday with a big escort of soldiers armed to the teeth and a plentiful display of machine guns was worthy to rank with the mammoth wartime convoys on the roads of Prance.

***

Today 150 motor trucks filled with provisions were convoyed thru the heart of London by a big detail of soldiers…but nowhere was any interference attempted. There were altogether too many machine guns in evidence, too many cartridge belts and wickedly glistening rifle barrels.

The government’s pride in the awe-inspiring martial panoply with which it has regaled London…is clearly shown in the official statements issued…

Firstly the Victoria Docks were occupied by troops, as if they were a strategic point in the heart of the enemy’s country. On Friday two full battalions of one of the crack guards regiments, the flower of the British Army, were transported in motor trucks across London and installed there for an indefinite stay. They were so thoroughly equipped for possible trouble with inhabitants of the tough dock region that they had a truckload of barbed wire for making entanglements.

A number of armored cars also went with them.

***

A motion by James Stewart of Glasgow to reject the regulation relating to the employment of armed forces in connection with the vital services was defeated in the Commons by a vote of 201 to 86. The members, wearied of arguments with the Laborites, did not even discuss the motion.

***

The government today made another appeal for volunteers to do police duty during the strike as special constables. Already 250,000 such constables have been enrolled…This force will be called the “Civil Constabulary Reserve.” It will be paid as a full time force…Those eligible for the new volunteer police force are officers and enlisted men of the Territorial Army and senior divisions of the Officers’ Training Corps and former military men who can be vouched for at territorial headquarters…Employers are asked to encourage their employes to enroll.

***

Orders issued at Portsmouth are to the effect that any order given to the naval personnel in connection with the services declared by a secretary of state to be vital becomes *’a lawful command” under the naval discipline act.

***

At the Bow street police court two men received prison sentences for being in possession of documents the publication of which would be in contravention of the emergency regulations…There was a reference to the return of the Prince of Wales from France on account of the general strike in these words:

“The Smiling Prince, who, it is understood, will be called out on strike by the Amalgamated Society of Foundation Stone Layers.”

The Final Betrayal.

THE method by which the British general strike was called off and the miners left to surrender or fight on alone was made clear by the controversy between Sir Herbert Sanduels, chairman of the coal commission and the leaders of the British Trades Union Congress.

Sir Herbert acted as the go-between for the Baldwin government but in an unofficial capacity.

In an endeavor to cover up the cowardice and stupidity they exhibited in calling off the strike at a time when at least a third of the trade union strength was still in reserve and the strike gaining impetus hourly, the Trades Union Congress officials have challenged Sir Herbert to deny that he was acting for the government and that the government had full knowledge of the contents of the memorandum on the basis of which the congress officials say they called off the strike.

THE reply of the emissary of British capitalism, with whom the Trades Congress officials entered into an agreement behind the backs of 5,000,000 workers, is very enlightening.

It shows that unknown to the workers the reformist leaders, instead of broadening the strike and accepting the challenge of the British government hurled broadcast throughout the world, were scurrying here and there in panic, anxious only to stop the strike and at the same time leave the masses ignorant of their treachery.

Confirmation of this fact was made by A.J. Cook, secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain in a speech delivered in the Rhondda Valley, Wales, on May 23.

IN this speech Cook made the categorical statement that he had never been bullied by government officials like he had by the officials of the Trades Congress to get him to agree to a reduction in the miners’ wages.

He characterized the calling off of the general strike as a “shameful betrayal” and stated that the speeches of Ramsay MacDonald and J.A. Thomas, labor party and railwaymen’s union heads respectively, “would be read by the working-class with shame.”

As the secretary of the Miners’ Federation, the largest union affiliated to the Trades Union Congress, it goes without saying that A.J. Cook realized the full responsibility placed upon him by such a public statement.

IF it had been possible to save the reputations of the MacDonalds and Thomases, it Is safe to assume that the government would do so. But the Baldwin government has its face to save and although MacDonald and Thomas and their kind have given sterling service to British capitalism—before and during the general strike—the British capitalist government lets its catspaws shift for themselves in accord with the ancient custom of dropping Jonahs to quell mutiny on the ship of state.

Sir Herbert Samuels said plainly that he told the Trades Congress officials time and time again that he was not acting for the government in view of the fact that the government had declared it would not reopen negotiations until the strike was called off.

Samuels stated:

“There was undoubtedly an honorable agreement between the Trades Union Congress and myself that I would use my best endeavor to secure the adoption of the memorandum’s proposals. Because I had been chairman of the royal (coal) commission, I felt justified in entering into such an agreement, believing any further suggestions I would make should not be without weight, although made in an individual capacity.”

SO the Trades Congress leaders entered into an “honorable” agreement with the head of the royal coal commission—the very body whose proposals the Miners’ Federation had rejected, whose proposals for placing the burden of the industry still more heavily on the backs of the miners were the direct cause of the strike.

An “honorable” agreement of a similar character was made by one Benedict Arnold and another British government in the struggle for American independence.

The Trades Congress leaders conspired with the most bitter enemy of the miners.

SIR HERBERT is typical of his class. He pointed out that “all but two points” of the unofficial memorandum on which the strike was called off have been accepted by the government. These two points are:

1. Provision for more than the regular unemployment pay for 130,000 miners who lose their livelihood thru the closing of mines consequent upon the reorganization of the industry.

2. A national living wage for the coal industry.

It is thus seen that the two points left out of the government’s proposal which was made after the strike was called off actually are the heart of the whole question at issue, i.e., whether the coal miners shall accept a reduction of wages.

Heartened by the duplicity of the labor officialdom the coal owners demand reductions far in excess even of those recommended by the coal commission.

MACDONALD and Thomas are exposed before the whole labor movement as men who, on the word of a tricky capitalist spokesman, without a shred of paper to bring before the striking workers of Great Britain who had left their jobs by the million to support the miners, called off the strike, left the miners in the lurch and halted the magnificent onward march of British labor.

Why did they act in such a secretive and cowardly manner?

Because they were afraid the general strike would be a failure?

Not at all.

Because they were afraid it would be a success.

They feared, just as much as did the capitalist class leaders, that the British labor movement would understand that it had the government to fight and that the labor unions would smash British capitalist government to smithereens.

There were no supporters of the workers in the ranks of the British government forces but there were government agents and supporters of capitalism in leading positions In the general staff of the Trades Union Congress.

This is the reason why the miners were forced to fight alone and why the masses of the British trade unionists arc turning on the reformist leaders.

Such was the pressure from below that the general council of the Trades Union Congress was forced to call a conference of union heads for June in order that the whole disgraceful affair be considered.

At this conference the basis was laid for the cleaning the leadership of the Trades Union Congress so badly needs before It can march as it will, unhampered by agents of capitalism in leading positions in its ranks, to its goal—a workers’ and farmers’ government.

PDF of original pamphlet: https://archive.org/download/TheBritishStrikeItsBackgroundItsLessons/Generalstrike_text.pdf