Wobbly organizer James P. Thompson brings the Good News to the mill workers of Mapleville, Rhode Island.

‘Slavery in Rhode Island’ by James P. Thompson from Industrial Union Bulletin. Vol. 1 No. 21. July 20, 1907.

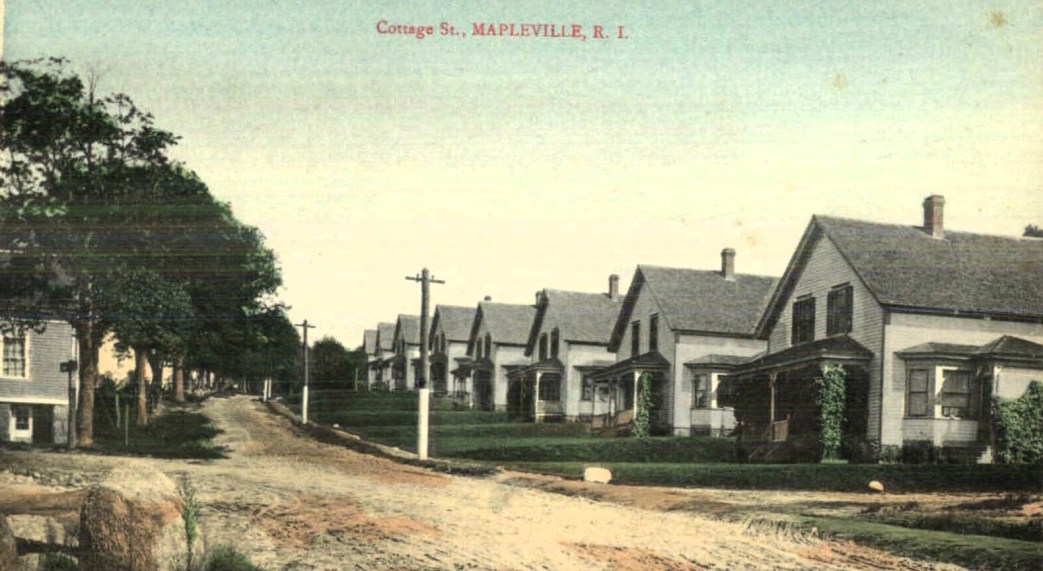

Mapleville, R.I., July 4. 1 arrived here Monday. In the afternoon a meeting of the strikers was held at which they voted unanimously to remain out and fight against the two-loom system to the bitter end. After the business meeting of strikers was over, we held a meeting in the open air outside of the hall. I addressed the strikers from an express wagon and, although they had been on their feet all day waiting for their pay and attending the meeting at the hall, not even having had time to get their supper, they gathered around the wagon and listened eagerly, as industrial unionism and the historic mission of the working class was explained to them, and at the close–by the light of “red fire” and lanterns–80 of them signed the application for a charter in the I.W.W. Then with three cheers for the Industrial Workers of the World the meeting adjourned.

The next day, Mr. Lloyd, the superintendent, after hearing the report of the committee, said he would like to meet all the weavers in a hall and have a talk with them. When this was reported to the weavers at their meeting in the grand stand at the ball park they voted to call a meeting for that same evening and invite Mr. Lloyd to address them. Of course Mr. Lloyd is a bourgeois, or thinks he is, which is worse, and so no common hall would do for him. He let them have the finest hall in town free of charge. He no doubt thought that if he came before them with a little “soft soap” and a large amount of “hot air” he might get them to go back to work, but he failed. He found himself up against a “bunch” who knew as much about wealth and how it is produced and distributed, as he did, and a sight more. He came out of the hall looking like “30 cents,” while the weavers again voted unanimously to fight to the last ditch. After this meeting was over, we held another meeting in the open air just outside of the hall and 45 more signed the application for a charter.

The name of the company is the Coronet Worsted Co. Total employed in the two mills here, 500. When the company asked the weavers to run two looms on fancy worsted they refused. and when the superintendent told them they must each run two looms on that kind of goods or get out of the mills, all the 180 weavers employed here walked out and nearly all of the other workers in the mills followed them, and as a result the two mills are completely tied uр. The solidarity and determination shown by the workers in this strike is something grand. Their motto is “an injury to one is an injury to all.” They know they are not fighting for themselves alone, but for all the workers in the textile industry. If the two-loom system is forced upon them it is only a matter of time when it will be forced upon the workers in other places. It is the thin end of a wedge, and the strikers know it and are therefore determined to win, and it is up to the other workers of this country, especially in the textile industry, to support them. This strike must not be lost.

If the two-loom system is forced upon this industry it means that one weaver must do the work that two are doing now. The demand for weavers will fall almost one-half, and many weavers will tramp the country looking in vain for work, while others slave their lives away working at a pace that kills.

Joseph E. Fletcher, the owner of the mills here, is a typical member of the “worthless class.” The $10,000,000 left him by his father has been increased to 20 or 30 millions, and of what does this wealth consist? It is composed of two elements, matter and labor. Its value is the amount of labor embodied in it, it represents the expenditure of nerves, brains, tissues and muscles of an army of workers, the unpaid labor of countless slaves. And yet Mr. Fletcher is not satisfied, he wants to squeeze still more labor out of his already overworked slaves, he wants them to work harder, twice as hard. It will kill them, it will take years off their lives, but that does not matter, it is the religion of capital; murder them, torture them, kill them by inches; capital must be increased. “Capital is dead labor, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labor, and lives the more the more labor it sucks.”

The workers are getting tired of slavery and so the number of “undesirable citizens” is increasing. They are joining the I.W.W., and just as the little corals by united effort cause great islands to rise from the depths of the ocean, so the workers by uniting as a class will cause the structure of a new society to rise within the old. They will build up an economic organization of their class, so powerful that they will rule the world, abolish capitalism and establish the cooperative commonwealth, a world without a slave.

The workers here are fighters and determined that if they ever go back into the mills here again they will go back industrially organized as a local of the Industrial Workers of the World, an organization which says “an injury to one is an injury to all,” and “labor is entitled to all it produces.” In joining the I.W.W. at this time they do not expect support from it. Only a few of the strikers were I.W.W. men before the strike. The first man asked to run two-looms, however, was an I.W.W. man. The workers here have always been liberal in supporting strikes in other places. For instance, they have been sending several dollars each week to the I.W.W. strikers in Woonsocket.

Mr. Fletcher has another mill at Central Village, and as I understand the I.W.W. has local there I may run down there after the meeting tomorrow and see what can be done.

James P. Thompson.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iub/v1n21-jul-20-1907-iub.pdf