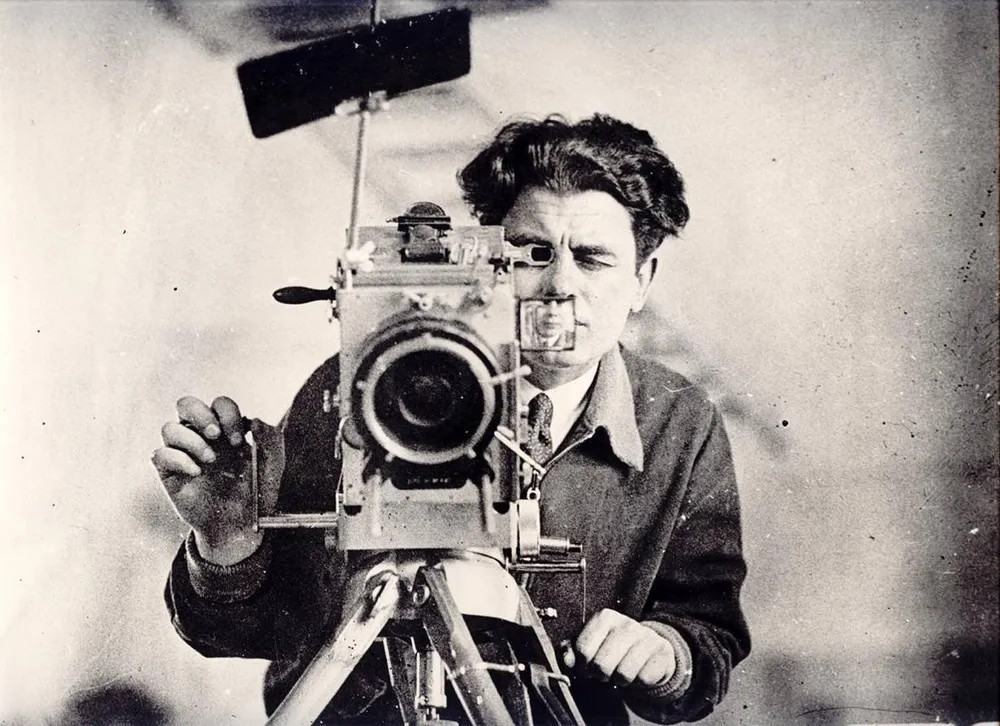

MacLeish looks at early Dutch radical documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens and the documentary medium in general.

‘The Cinema of Joris Ivens’ by Archibald MacLeish from New Masses. Vol. 24 No. 9. August 24, 1937.

The newest production of the Dutch master raises some questions on documentary films

ONE trouble with movie criticism is its assumption that the moving picture is a dramatic form to be judged by dramatic standards. Actually the moving picture is a fictional form. The most casual attention to any standard Hollywood product will discover that fact. The construction of the standard Hollywood picture is narrative, not scenic, and its persons are “characters” rather than dramatis personæ.

Furthermore the fictional prototype of the commercial moving picture is not the novel but the magazine short story. Both in out- ward proportions and in inward realization the Hollywood movie corresponds to the familiar Saturday Evening Post time-passer. The only important distinction is a purely mechanical one. In the one case the reader has to take the trouble to read and visualize for himself, whereas in the other his reading and his visualizing are done for him. Premasticate and predigest the thin gruel of a magazine short story, and you have a Hollywood picture. Even when the original rough- age to be premasticated is a full-length novel–even when it is a full-length novel of the bulk of Anthony Adverse–the result is still a short-story’s worth of short story.

The point is worth making because it helps to put the work of Joris Ivens where it properly belongs. The tendency of the critics to treat the documentary film as necessarily less “interesting” than the commercial film—their tendency to praise it, if at all, as brilliant photography, or instructive reportage, or “worthwhile art”–is a natural result of the assumption that the standard commercial picture is theater. The attitude of the movie critic is that of a dramatic critic reporting on a Burton Holmes travelogue which has taken over the local theater for a night. If they like it, they will say so. But they will say so with a difference. They will say so with an implied “You understand, of course, this isn’t really a movie.” Even that amazing film, Man of Aran, which the critics in general liked, was praised with that implicit reservation. The public was told that this was a film it ought to see. But it was also given to understand that this film was not like other movies. It was not, that is to say, a piece of theater. The fact that it was presented as considerably “better” than the run of other movies did not counteract the impression that it was different.

The public does not go to see what it ought to see. It does not go to see what is “better.” The consequence is that the public stays away from documentary films by the million, and that the type of moving picture which ought to have, and which is made to have, the broadest popular appeal has a very limited popular audience. Even the best pictures of that type are apt to begin life in a smallish radical or art theater and end it in a lecture hall.

If the basic critical assumption as to the nature of the moving picture were corrected, a considerable part of the initial disadvantage of the documentary film would disappear. So long as the commercial movie is thought of as theater, the documentary film must necessarily be put in a category of its own, for the theater, aside from the W.P.A.’s Living Newspaper, has no place for the documentary film’s direct and explicit actuality.

But the moment the movie is put down for what it is, a fictional form deriving from fictional prototypes, the place of the documentary film becomes obvious. It bears the same relation to the usual commercial picture that the realistic novel bears to the commercial short story. It belongs not to a less “interesting” but to a more “interesting” category. It presents the actual life of actual men not falsified or foreshortened for entertainment purposes but organized for understanding.

Considered in these terms, there can be no doubt that Joris Ivens ranks not only with the great makers of documentary films but also with the great makers of moving pictures. He has all the qualities of the competent realistic novelist including certain qualities which most realistic novelists lack. In so far as any observer may be said to see the contemporary world, he seems to see it. He does not set out, as so many radical novelists do, to discover his preconceptions. He is both willing and able to report what actually exists. Furthermore, he has a sense of humanity which any novelist might well envy. No one who sees The Spanish Earth (55th Street Playhouse, N.Y.) can fail to be impressed by the extraordinary realization of character in the faces of his people or by the pervading tenderness and virility of his scenes. Finally, he is truly an artist, truly an inventor of forms. In no novel I have ever read have I felt more sharply the true shape of the crisis of action, the cross-pull between mortal alternatives, than in Ivens’s The New Earth, where the completion of a dyke becomes the symbol of the whole history of man’s struggle against the sea.

It would be foolish to suggest that a mere change in critical terminology would bring to such pictures as Ivens’s the public for which they were made–the public which would delight in seeing them. I make no such suggestion. I do, however, believe, and do mean to say, that the kind of criticism which treats Ivens’s work as something hors de concours and throws him, by way of consolation, the invidious title “artist,” is criticism which rests upon a misapprehension. Artist, Joris Ivens is. But not in the sense in which the word is used in Hollywood. And whether artist or not, his pictures are much more like the movies than are the movies themselves.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1937/v24n09-aug-24-1937-NM.pdf