Without its own social, sports, cultural, and arts institutions the working class will find it impossible to have a politics of its own. Ed Falkowski went into the mines of Shenandoah, Pennsylvania as a teenager and quickly became a radical activist in the UMWA. Always an intellectual, he attended Brookwood Labor College in the 1920s and began writing. In 1928 Falkowski, traveled to Germany as an exchange student and immersed himself in Berlin’s left life reporting of his experiences in the U.S. radical press

‘Recreation for Unity in Germany’ by Ed Falkowski from Labor Age. Vol. 19 No. 6. June, 1930.

Workers’ Own Sports, Plays and Art Hold German Workers in Labor Movement

A GERMAN worker usually knows more about Bruno Schonlanck, writer of workersongs, than about Chopin or Mendelsohn. The radical worker knows the ballads of Eisler, neglecting those handed down by regular institutions. And he may know much more about Eisner, Holz, or Husemann than about Einstein, or Tardieu, or even Hindenburg.

The German Labor Movement has developed its own labor culture to such an extent that a worker can find satisfaction for a good many of his spiritual and cultural and emotional desires without going outside of the Labor Movement.

Labor drama, the beginnings of a worker-cinema, lectures, schools, music and dances, sports and hobbies, literature and newspapers, stores and even factories, may be found within the bounds of the Labor Movement.

It is true that the political tension in Germany has reached a high point; that party denounces party, and the differences between extreme rights and extreme lefts are not nearly so broad as those between social democrats, and the next strongest labor party, the communists.

One group of workers applauds the defeat of another. When the police club a thousand communist skulls, the social democratic newspapers shout with joy, while when the social democrats become intimately involved in scandals, the communists find this a cue for booing down the other side.

But what is significant is that these are all workers, men of mine and mill, throwing themselves with throttle wide open into the political fight. Most workers of Germany belong to some form of industrial organization, from deep yellow to burning red. They are deeply political— political on the job, at home, in the street. They breathe politics, and discuss it.

Politics in Germany decides the size of one’s loaf of bread tomorrow. It settles the price of margarine, and juggles with unemployment insurance, and such other security as the worker has in a world old, tired, and to him, very unsafe.

For social insurance in Germany is not so securely established that one can sit back and watch it do its stuff. One must act every day to defend it from the encroachments of industrialists whose power since the war has grown by leaps and bounds. No autocrats of the old order wielded the power the German coal and steel kings command today.

II

To the new political power of the industrialists is added another menace to German workers in the form of the so-called Werksgemeinschaft movement—the German name for the company union.

Not only does it creep into a plant by means of subtle propaganda, but in mine-and-mill-villages, where the will of the Direktor is often the supreme law, adherence means very special benefits in the form of increased wages, better job, vacation for the children, work for the oldest son, better treatment when one is ill, cheaper potatoes, etc. Even the leaky roof of a company-unionist’s home will be sooner repaired than that of another worker’s.

The monotony of a worker’s village life is broken by beer-evenings during which the corporation pays for the beer consumed, and the hot dogs. A company orchestra provides inspiring concerts, and Christmas time means presents for the kiddies, and cake for the wives—all paid for by the company.

Such propaganda is difficult to combat, in view of the worker’s lean situation. If he strikes, at the end of two weeks he is helpless. The unions are not too prosperous since the inflation, while wages are usually miserably low with a view of crippling the worker’s militancy. If he is militant, well and good. Two weeks on the street—or even thrown out of the company house and out of a job (and it takes half a lifetime to find another job sometimes) will soon bring the renegades to terms. “They have it too good!” is the company’s point of view, and uses the strike as a pretext for further depressing the actual conditions of workers on the job, in spite of nominal improvements written into renewed labor contracts with unions.

Here is a new situation for the German unions to face–something they have never faced before. It means that such cultural methods as have been developed must be further intensified to counteract the danger.

But German unions are not asleep. They work with camera and pen and brush. Poem and song and play and music are weapons in the hands of the movement. Importation of Russian films is encouraged. It is true that the radical movement is always a forerunner in these things. But the older unions are not too blind to pass up a good thing. The fact that communists compose many lively songs doesn’t prevent the other unions from trying to imitate a good example.

In this respect one must admit a good deal of fairmindedness exists among the more intelligent leaders of the unions who, in spite of the high political temperature, do not permit party-blindness to interfere with their appreciation of a good thing no matter which side brings it out first.

To this extent at least there is a unity in the German Labor Movement.

Ill

While in the United States the primitive task of convincing a worker that he is a worker still remains to be done, in Germany the job is that of trying to win him into a particular camp. The worker has long since gone through the depressing stages of finding out to which class he really belongs. He doesn’t have to read Karl Marx to know this.

The various unions do not exclude one another—do not even in a sense, compete with one another, because they each express fundamental lines of conviction.

The Christian unions are anti-freethinking; the social democrats fight for a liberal point of view; the opposition unions are out-and-out radicals, while the Hirsch-Duncker takes in small skilled groups who are too independent to join other unions.

When a union covers a territory in its usual house-to-house campaigning for members, it tries to win the unorganized workers either for itself, or to persuade him to go into the other organizations. Cases are familiar of the Christian union taking members for the Social Democratic (so-called Free) unions, and vice versa.

In signing new agreements, the main-line unions cooperate completely, and see to it that they are enforced.

But this apparent harmony doesn’t mean that their paths are smooth and frictionless. In political campaigns, in plant committee elections, etc. each directs the full force of its power against the other. The result is that each is always in fighting trim, knowing that it can rely on assistance from the other union only when it can command respect through its own power.

The radical unions, a party of protesting outcasts from the regular unions, come into plant-power at various points where discontent is keen, and other unions ineffective. These groups are bitterly opposed to the regular organizations, and neither side gives the other quarter.

IV

Each organization has its weekly paper furnished to its members. Besides, there are many monthly publications, special magazines for plant-committeemen, dealing with methods of handling plant situations legally. Research departments dig up statistical material, while university-trained workers, or graduates of labor colleges, write up the news, or do active work among the workers, such as representing their claims against the corporation in the labor courts, etc.

Plant committee campaigns keep alive political issues inside the plant. Each union posts its candidates, and urges its propaganda on the workers.

Once a week the plant committee gets together where convenient to receive complaints from workers desiring assistance. The worker’s life is rather complicated. There are pension claims (partial or full) ; reductions of dues for social insurance; complaints about the job or protests against being fired, or being paid under the minimum scale.

In most of these matters he requires the help of skilled men who know how to make the existing laws effective where stubborn corporations try to override them.

Mentioning these things in what purports to be a glance at the cultural activities of the German Labor Movement, may sound irrelevant. Yet this is the situation that makes a labor culture possible at all. The life of the worker is bound up with that of the plant; and through it, with the union, which stands between him and the brutality of the industrialists.

The worker is so completely antagonistic to the employer that even where he reads no paper, and is indifferent to unionism, he will resist all efforts of employers to salve him with words. It is only when the employer ventures into the more concrete ways of the Werksgemeineschaft that the worker may be induced to part with his soul that he might have a company pig in his pen.

The unions conduct night-schools for young workers desiring to learn the elements of unionism. From the brighter ones students are selected for intenser training, at first to labor Sunday schools (all expenses covered by the organization), and then a few weeks or months in a higher institution.

At Konigswinter is a labor college where the Christian and social democratic unions send many of their students, including elected plant-committeemen who are usually sent there for a few weeks of intense study of plant-committee laws.

A selected few are sent by the unions to Dusseldorf, or Frankfurt universities. From this class come the economic experts, journalists, etc.—men who will handle the more complicated work of the organization.

Besides this there are many schools such as the Metallarbeiter’s school at Durrenberg, where the individual unions send their students for special training.

This means that the Labor Movement has a sound intellectual basis for its work. There is less hit-or-miss about the movement than there is in the United States. At the top is a structure of skilled experts, many of whom attend international meetings, etc., and who try to look at arising situations from a scientific and world point of view.

No genuine labor culture can arise out of unaided enthusiasm. Trained skill must be put to use, and the German unions have long appreciated this fact.

In any consideration of labor culture, one must ask what is the difference between labor culture, and culture in general. Is it good, for instance, that a worker know more about Brust, the father of the Christian unions, than about Thomas Mann?

The fact is that labor culture does not exclude any real culture. It only means the projection into all arts, sciences, philosophies, etc. of a labor point of view, in the same sense as the average newspaper critic gives a middle-class point of view—a Rotary club’s verdict—on the intellectual or political happenings of the day.

Certainly what a play means to a business man is not what the same play would mean to a worker. There is no sure or absolute standard of art.

All art or science stands, outside its frame of definition, in a certain light of interpretation. It is necessary that the worker cease adapting a point of view alien to his interests. Without ignoring the significance of any intellectual endeavor, he can still look at it from a worker point of view without insulting the “pure art” or science theory any more than middle class intellectuals insult it by dressing it up in the ideological clothes of their standing.

VI

The immediate situation, however, is such as calls for competition between the Labor Movement and the financial interests for the emotions of the workingman. Cinema, newspaper, book, picture, have become mediums through which capitalists reach for power into the emotional capacity of the worker.

Where the battle takes place before one’s doorstep, and events don’t wait for long-run solutions one has to act even when the chance of making a mistake is rather large.

Under such auspices has what we have of workers’ culture in Germany been rushed to life. One might say it has had a premature birth, but it is a hardy infant.

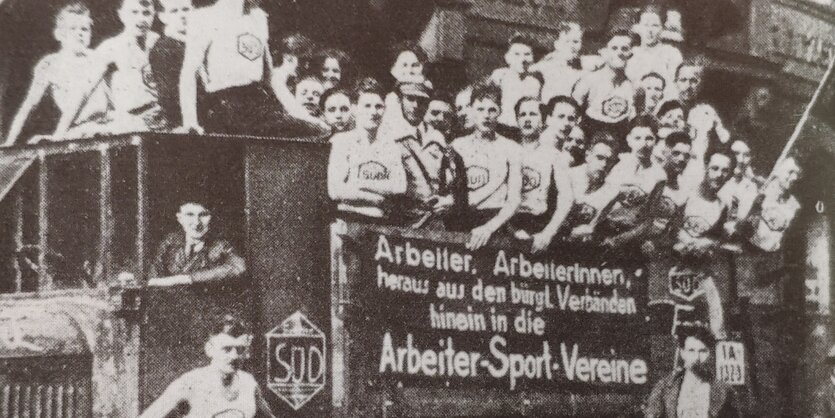

Nearly every work-town has today its theatrical groups where workers not only stage their own plays, but write them, and compose the songs. Worker-orchestras, singing societies, sport organizations are general. They provide any number of affairs for the worker’s entertainment—dances, lectures, plays, coffee-parties. The workers, whose lives are hungry for emotional content, turn out en masse.

Anniversaries are celebrated on massive scale, as for instance the 50th anniversary of the Free Miner’s Union at Dortmund, in 1929, or even, to take an extreme, the Free Thinker’s Fest in Dusseldorf.

Bands, orchestras, parades, dances,—a labor carnival takes place, the streets filled with workers from all parts of the country. Everywhere are brilliant posters appealing to the unorganized to join the union.

Labor poets are not only encouraged, but the unions issue bound editions of their poems, as those of Kessing, for instance, from the Christian Miners Union, and those of Kalinowski, from the Free Union.

In Berlin, the IFA (Interessengemeinschaft fur Arbeiter-Kultur) has become the central organization of nearly thirty groups. These groups represent sports, literature, theatre, languages (Esperanto and Ido), anti-alcohol, radio, phonograph records, songs,—even the Piscator group is affiliated.

IFA’s contact between the worker and the professional artist means that the latter is ready at all times to help the worker in his efforts to stage a play or plan such exhibitions, for instance, as the recent display of “worker-culture” in Berlin, which called for much professional skill in decorating.

The worker is hungry for worker literature—stories of the mines and mills; plays dealing with experiences he can share; novels about the Ruhr. “The Kaiser’s Coolie,” “The Burning Ruhr,” “Told by a Kumpel,” are titles of some of the books most widely read by workers. Upton Sinclair and Jack London are very popular, and every worker knows something of Ben Lindsey’s ideas. One of the most widely purchased books for workers is Dr. Hollein’s “Pregnancy-Compulsion—and No End!” which deals with contraceptives in plain language. Even the poorest of the poor have a greasy copy of this book somewhere around the house.

The hunger of the worker for culture is intense—so intense that much of it overflows into the conventional channels. But the Labor Movement is awake to the situation, and is continually experimenting, planning, studying.

The problem of holding the interest of the worker is a difficult one, but can partly be solved by getting the worker himself to cooperate, instead of being always the passive spectator. Things do not seem so dull when you yourself help to make them, and realize the difficulties to be overcome.

Sometimes it looks as if labor drama, poetry, etc. lacks humor and is too grim and realistic. More temperament is needed, for laughter is as good a weapon as tears, if not sometimes a better one.

The first labor comedy will be an event! But with the workers’ burlesque troupes—traveling groups of actors who acquire no scenery or costume, and whose stage is often a street or a pier, an excellent beginning in the right direction has been made. Anyone who has seen their performances—their satirical stunts, songs and wit, cannot resist seeing them again and yet again. They write up their minstrels themselves, and every two or three weeks, have something new. The workers come to see them regularly, and never go away disappointed.

Perhaps here one sees a propaganda and culture method which must become more general in the Labor Movement throughout the world.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n06-Jun-1930-Labor-Age.pdf