An extraordinary addition to the history of the Revolution in the Russian Far East and Siberia from two comrades long part of the U.S. revolutionary movement. An extensive interview with U.S.-born Communist Gertrude Tobinson, first wife and comrade of Alexander Krasnoshchekov, the first Chair of the autonomous Far Eastern Socialist Republic headquartered in Ulan-Ude, Krasnoshchekov emigrated to New York in 1903 where he joined the S.L.P. and then the I.W.W. and wrote for the Yiddish and Russian revolutionary press. In the exile circle that would join with Bukharin, Kollontai, and Trotsky in March, 1917 to form the Internationalist Group, Krasnoshchekov returned to Russia in 1917, joined the Bolsheviks and settled in Vladivostok where he was central to establishing the revolution there. Returning to Moscow in 1922, he was elected to the Presidium of the Supreme Economic Council of the RSFSR. An affair with Lily Brick in this period brought on the divorce with Gertrude who returned to the U.S. with their younger daughter. Charged with misuse of funds in 1924, he was sentenced to four years in prison, but amnestied the following year. For the next decade he worked on agricultural development and Soviet banking before his arrest on July 16, 1937. Yet another victim of the purges, this founder of Soviet power was shot on November 25, 1937.

‘The Soviet of the Far East’ from The Liberator. Vol. 2 No. 4. April. 1919.

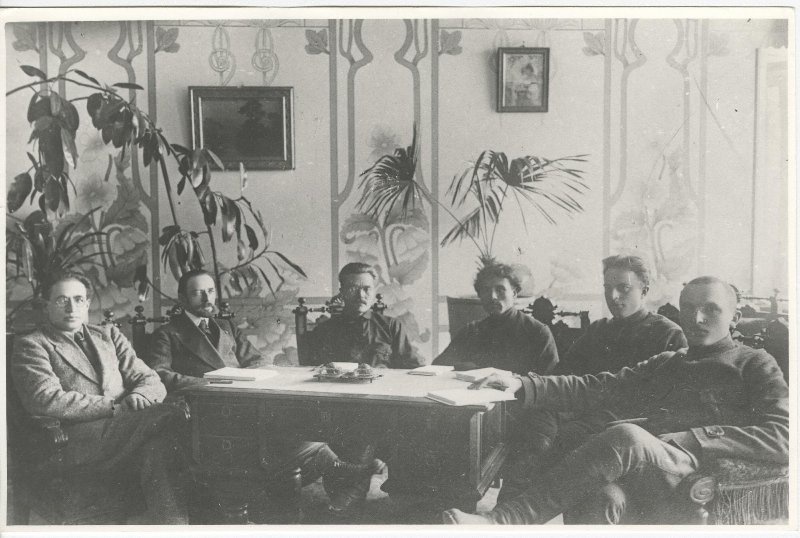

Verbatim Report of a Conversation with Gertrude M. Tobinson, wife of Krasnochokov, President of the Far Eastern Soviet in Siberia

MRS. TOBINSON, what was your husband’s business in Chicago?

A. He was the superintendent of the Workers’ Institute. It is an institution controlled by the working men–a sort of proletarian university.

Q. Was your husband born in Russia?

A. Yes, he was born in Kiev. He came to this country in 1902 and studied at the Chicago University, and worked at painting. Then he studied law and passed the Bar examinations in 1911. He had an office and practiced law for five or six years. It was in July, 1917, that we left for Russia.

Q. Did you go back at the expense of the Russian Government with the rest?

A. Our party consisted of about a hundred Russian people. Yes, we went at their expense.

Q. That was at the expense of the Kerensky Government?

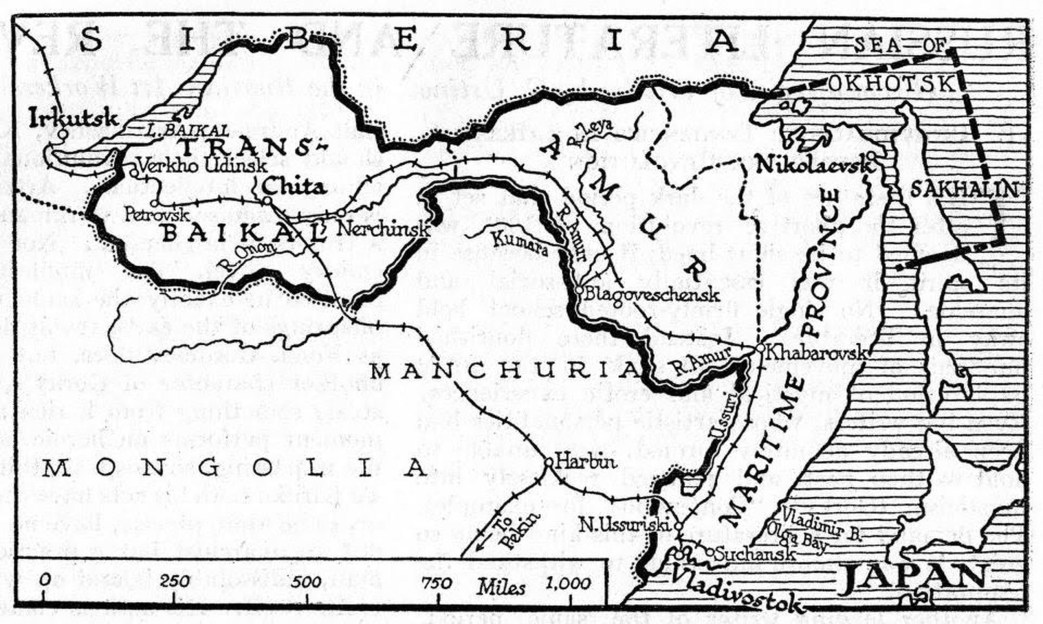

A. Yes. And when we came to Vladivostok–the second day after we came, my husband was made the secretary of the Central Union. There were many who knew him from Chicago of course. We stayed four weeks in Vladivostok and then he was urged to go to Nikolsk, a small city about six hours ride from Vladivostok, and he was elected there very soon to be a member of the City Soviet. That was in Kerensky’s regime. He tried to organize the soldiers and peasants in the villages into Soviets, and he was elected chairman of the Soviets.

Q. Did Kerensky’s regime encourage the formation of the Soviets?

A. Oh, no. There were Soviets while Kerensky’s regime people was in existence, but they didn’t have any power.

Q. When you were forming these Soviets, was that consciously with the purpose of another revolution?

A. Yes. We all knew that the time would come when the workers would get the power through these organizations…My husband was a member of the City Soviet about four months, I guess, and then the crash came. The Kerensky regime fell in Russia, and as soon as it fell in Russia, naturally it fell in Siberia without any revolution and without any fighting or bloodshed. The Soviets simply took over the power.

Q. He was Mayor and Chairman of the Soviets, both, wasn’t he?

A. Yes. Then immediately they called a conference in Habarovsk of all the Soviets of the Far East. That was in January 1918, and he was sent as a delegate to that conference. He was elected Chairman of the conference–temporary chairman, and afterwards Chairman of the State Soviet.

Q. Of the whole Far East–and how much does that include?

A. Well, Louis Edgar Brown of the Chicago Daily News Staff wrote once in a newspaper that he found Tobinson the dictator of a territory one-third as large as the United States. Of course the population isn’t as large. We had in Vladivostok about 100,000, and in Habarovsk about 50,000. Brown called him “dictator” only because he had a great influence over the people, over the peasants and workingmen. They loved him; he was a teacher and comrade. He would sometimes work for eighteen hours a day with the Soviets. In the evenings he would go out and teach the people, eat with them, and sleep with them.

Q. Is he back in America?

A. No, he is not back; I don’t know where he is.

Q. Up to the time when this great change took place all over Russia, when the Soviets got in power, the industries and the land and the various economic enterprises of Vladivostok were still in private hands and were still private property?

A. Yes.

Q. Had the workers made any attempt to control or to appropriate them under the Kerensky regime?

A. No, they were just organizing towards this change.

Q. Your husband, while he was Mayor under the Kerensky regime, functioned exactly as a socialist mayor would function here in America?

A. Yes–only at the same time he educated and taught the people.

Q. But there was no form whatever of nationalization or municipalization of industry?

A. No, the Soviets were simply educating and organizing against the Kerensky power all the time.

Q. Now, I would like you to describe as accurately as you can just what happened as soon as the Soviets got control of the situation there.

A. Well, they went very slowly. First, they organized the State Soviet, the central power–the State Soviet of the Far East. Next they went quietly to work and nationalized the fleet. You know the Far East is surrounded by the Amur River; there are many sailors and many boats that belong to private people, and they nationalized these first. Then they nationalized the mines. First, of course, they would call a conference of the peasants and miners, and these would pass resolutions favoring the nationalizing of the mines, and then they would proceed to take them over.

In Blagovieschensk a big fight was put up by the White Guards and the Cossacks. While this conference was in session, and after the resolutions were passed they surrounded the building and arrested 400 peasants and workers and all the members of the conference. My husband was arrested among them, and kept in prison for six days.

When the peasants of the district learned that the members of their conference were arrested, they came running from all the villages and all the cities around, not organizing at all but just pouring out, about 10,000 of them a day, with hammers and hatchets and wood and whatever they had in their hands, to free the members of the conference. It happened just in one day–the minute they learned that the conference was arrested. Everybody came, women with wagons bringing bread and meat, cooking right there in the open air for the fighters. It took them about a week to recapture the city. They had to put up a hard fight because the White Guards and the Cossacks got the help of the Chinese, who were just over the frontier.

When the Red Guards had captured the depot, and the White Guards saw that they were coming back strong and would soon take the prison, they issued an order to shoot Krasnochokov. But just at the same time the keys of the prison were given over to the Red Guard. They came, opened the doors and took out all the prisoners. They took him out and carried him almost all day on their shoulders in the streets. Afterwards he stayed there for six weeks, organizing the city, putting the Soviets on a solid footing, and nationalizing the fleet and the gold mines and coal mines. Blagovieschensk is a big city, and there is plenty of white flour and plenty of food there, and so the bakeries also were nationalized, and things were sold at half the price they had been in private hands. And the hotels were also nationalized, and the moving pictures, etc.

Q. Were such popular demonstrations organized in any way?

A. Usually it was spontaneous.

Q. Did you say they came across the country in wagons or in trains?

A. They walked and came in wagons from the surrounding villages. Many times they walked a whole day, or a day and a night, to the front. They kept on this way for four or five days-coming more and more until there were enough to get back the city.

Q. These mines that were nationalized, were they owned by Russian capital?

A. Yes, Russian owners. I once met the wife of a former owner of the mines. She didn’t know who I was, and she just went on telling me about her hard luck, and how now they had to live quietly on a farm. “Of course we did get away some money,” she said, “and so we live quietly, and wait until the Soviet power is abolished again, and we hope we will get back our mines.” I said: “What does your husband do now?” And she said: “Well, he has to work; he works in the mines and gets wages.”

Q. Now those mines that were nationalized by an edict of the Soviet, the titles were thereby transferred from the hands of the capitalist class, so to speak, into the hands of the Russian Republic, but what happened after that? Who ran those mines? How did they organize the work in those mines, and to what organization was given the power to regulate all the internal affairs, and who employed the men?

A. First of all, they organized unions-industrial unions. There were no unions there before or if there were, they didn’t have any power. Now only the unions have control over the shops and factories.

Q. And these unions were responsible only to the Soviet?

A. Every union had a representative in the Soviet–every industry. If the union consisted of more than three hundred it had two representatives. If it consisted of three hundred it had one representative, who knew all the inner affairs and protected the union.

Everyone the manager and the common worker–received the same wages–four to five hundred rubles a month, and the Commissars also received four hundred rubles a month. The President of the State Soviet received four hundred rubles a month.

Q. Now those managers, those engineers and the highly technical experts that manage industries, you know, are generally selected by the capitalist class, and they don’t come out of the working class. Were those men, the same old managers belonging to the bourgeoisie, employed by the workers, or did the miners themselves develop–

A. Well, many of the experts didn’t want to work. The managers would sabotage against the Soviet and the unions–and simply fold their hands and say, “We won’t work with you.” And they finally would go to Shanghai or Japan and join some counter-revolutionary plot. But many of them rolled up their sleeves, and helped us in the work. They remained on the job at our salary.

Q. And in other cases the workmen would select someone from among themselves to be the manager?

A. That is exactly how it was–in case they didn’t get an expert. The Soviets also tried to organize the unemployed–tried to give them work so that they should produce something. All the unemployed were put in one big building, and everyone had to work. They produced clothing and hats and shoes and everything in that building. It was called by a Russian name which means ‘Work for the Commune.’

Q. And they were paid regular wages?

A. Paid regular wages.

Q. Could you tell us something about the schools? Did your children go to school under the Soviet regime.

A. Yes, my children went to school. We organized the schools. The teachers also formed a union and called a conference and laid out their program–how they wanted to teach the children and what was best for the children. Of course, this was probably abolished when the reactionary power took control again. I spoke to many teachers before–I left, and asked if they would continue teaching under the old laws again, and they said: “No, we are going to quit teaching in the cities and go to the farmers and villages and teach quietly, where nobody can interfere with us.

Q. When the teachers organized a union and took over the schools themselves, did they improve them?

A. Yes, they improved them greatly. They tried to bring the free spirit into the schools. They tried to learn to know every individual child, and they would go home to the mothers and learn their life at home and they would find out the child’s position and the child’s background, and would act accordingly with the child. In the classes every morning the children would elect their own chairman for the day, and the teacher would just sit aside and watch them. Then if anybody had to be punished they wouldn’t come to the teacher, but would call a meeting–a revolutionary tribunal–and decide what to do. Of course it was somewhat comical, but the children would rarely do any mischief because they would be ashamed before each other. I spoke to many young teachers and asked them if they had ever heard the name of Montessori or Ferrer, and they said, “No.” But they had the same ideas. It just came natural to them.

Q. Did you stay there long enough to see whether the people in general seemed more healthy and happy or were they worried and was there a great deal of trouble?

A. No, they were not worried or troubled. The people were very happy because of the fact that they lived better economically under the Soviet Government than they had lived before. The wages were higher, bread was cheaper, and the theatres and moving pictures were better and cheaper. We had a Soviet Theatre. Of course the workingmen and the peasants could hardly reach the theatres at all before, and they all enjoyed them under the Soviet Government.

Q. Was it a free theatre?

A. Not free, but cheaper. It was a cooperative theatre.

Q. What about the priests and the ministers of religion and all that?

A. They all opposed the Soviets.

Q. What is the relation of the people to the church? Do they neglect the church?

A. Yes. You see before they really didn’t have any other enjoyment or any other amusement but going to church. Under the Soviet there were more meetings and more lectures and theatres and moving pictures, and they would go to the churches more rarely. The priests didn’t like that. There were many days that the White Guards and the reactionary power would try to rise against the Soviets, but they had very small power because the people wouldn’t back them. They didn’t have any ammunition or arms, and so they just did their howling in the streets and then went home to sleep.

Q. Did you have to keep a lot in prison?

A. Yes, but we never kept them for long, because the Soviets in Siberia felt strong, and they were not afraid of the counter-revolutionists. They knew that they didn’t have any power at all. The people and the soldiers were all with the Soviet Government. They really loved the Soviet Government and they wanted to fight for it.

Q. The bourgeoisie–the few that there were around–they were living merely on the actual cash that they had, were they?

A. Yes, most of them lived on what they had before. Many of them, though, went to work, because we invited anyone that wanted to work to become a member of the union and take a job, and they could become managers or select any work that fitted them.

Q. Were there any executions of counter-revolutionists in Siberia?

A. No, not a single one during the nine months–of course we had fights. While the Soviet Government was in power, it always had an army standing guard on two fronts. One was in the Central part of Siberia; the other near the Chinese frontiers.

Q. What did you start to say about nine months?

A. I said during the nine months that the Soviet was in power there wasn’t a single execution. Not a single death-sentence imposed by the Revolutionary Tribunal. We were most all of us against capital punishment. We had them in prison, those that were dangerous.

Q. How long were the sentences of conspirators?

A. They were indeterminate–just until we felt strong enough to let them free.

Q. Say that again.

A. Well, the Tribunal decided that they would not give or issue any sentence. We kept them in prison as long as we felt that they were dangerous. As soon as the Soviet felt that they wouldn’t do any harm, they let them free. We had many counter-revolutionists that became sympathetic to the Soviet afterward, some from necessity and others from understanding.

Q. Will you tell us your viewpoint about the Czecho-Slovaks?

A. At first the Czecho-Slovaks came through Siberia with the intention of going to the French front. Many regiments stopped in Vladivostok, and of course the Soviets gave them the best reception and the best buildings, thinking of them as guests and trying to accommodate them. But then many regiments arrived in Central Siberia carrying Russian arms with them, and the Central Siberia Soviet became a little suspicious, because the Russian arms could not be any good in France. So they asked them to leave the arms in Siberia–the rifles and the guns. They refused to do that and the Red Guards surrounded the trains, and wouldn’t let them proceed to Vladivostok. A good deal of trouble followed, but finally we tried to come to an understanding with the Czecho-Slovaks. We organized a peace conference in Central Siberia, to which all the cities should send delegates and the Czecho- Slovaks should send delegates. The conference took place in Irkutsk. While the peace conference was in session a shot was heard outside the depot where the trains were–the Czecho-Slovak trains. Of course, we don’t know by whom that shot was fired. Supposedly it was fired by some of the counter-revolutionists trying to make trouble. Well, anyway, one Czecho-Slovak was wounded and then the fight began. The Czecho-Slovaks fired from the trains and the Red Guards fired back. It was a two-day fight. Very many wounded Czecho-Slovaks came to us in Habarovsk and we shipped them to Vladivostok. The Czecho-Slovaks heard the news in Vladivostok and with the help of the Japanese and the English they arrested the Soviet in Vladivostok, without giving them time or helping them to investigate by whom that shot was fired or who started the trouble. They just simply jailed the members of the Soviet. While they were being arrested, one member shot himself in the Soviet. He didn’t want to give in. He knew what was coming. It came so suddenly they weren’t prepared for a fight. The shops were busy and the sailors were at work.

After the Soviet was arrested there were about three or four days of fighting. Many factories wouldn’t give in until they killed out everyone.

Q. What did they do with the leaders of the Soviet?

A. In Vladivostok they are keeping them in prison. When they took Habarovsk, however, they put out sixteen people in a row and shot them, many of them teachers. Some of them were the most intelligent people we had.

Q. What had become of your Government–the Commissars, had they gone farther away?

A. When Nikolsk and Vladivostok were taken we organized a strong army and tried to put up a fight. We held the front four weeks until the English and Americans came. The Czecho-Slovaks and Japanese could not take Habarovsk; for four weeks they were put back. During that time a special conference was called in Habarovsk of the remaining Soviets to decide what to do whether to retreat or fight on. The people would not listen to giving up the power. They wanted to fight. Of course they couldn’t see the uselessness of it as the leaders could, but the leaders urged them to retreat and wait until the allies should come to their senses. The commissars and leaders retreated in two boats to the wilderness alongside the Amur. I left them about two weeks before they retreated, taking my children to Nicolaievsk and waiting there for a boat to take me to Vladivostok. It took me six weeks to get to Vladivostok. During that time I was recognized once, and arrested, and my cabin was searched, but I was allowed to go on. When I came to Vladivostok I read in the newspapers that some of the Commissars had been caught and among them my husband, and they were the news was that he had been shot.

The last time I spoke to him was when I was waiting in Nicolaievsk for the boat. The day they were to leave I spoke to him over the long-distance, and he said: “We are leaving We are leaving at 6 o’clock in the evening.” He just told me that they were leaving for business,” and I understood that they had given up.

Q. You didn’t tell us about the nationalization of the land, I wish you would describe how that was done. Were there any fights about the allotment of it?

A. No, there were no fights. Of course, there were some small misunderstandings, but they called meetings, and people would explain to each other what was being done, and they always came to an understanding. They didn’t want any fights. I think they are very good-natured people.

Q. Were there large estates there?

A. No, in Siberia there aren’t. They are just settlers, you see. I think they had it harder in Russia–in Central Russia—than in Siberia, because there were great landowners.

Q. And during the summer when you were there all the peasants went to work and tilled the land?

A. Yes. Many soldiers that were set free went back to their homes and farms and cultivated the land, and they were really expecting to have a very good crop. They had most of them tried to put in an eight hour day’s work, and they expected to have enough bread this winter to feed Russia–to feed Central Russia. And they would have if it hadn’t been for the counter-revolutionary uprisings and for the attacks of the Czecho-Slovaks and the armies of the Allies. They would no sooner start to work than they would have to leave their tools and take a rifle in their hands and go out and defend themselves. And so it was whenever we wanted to do any constructive work. Even in the State Soviet they would have a meeting about organizing some important work, and then a telegram would come of an uprising, and they would have to leave the meeting and raise an army. We never had two months of quiet to show what the Soviet could do.

Q. When anything like that happened, did you need to do any urging at all? Did the people just simultaneously throw down their implements and go?

A. Oh, yes, they just went–happily.

Q. When they went to fight, what did they think they were fighting for or against?

A. They thought they were fighting for the preservation of the Soviets.

Q. Were the ordinary people quite conscious that it was a new kind of political and social life they were defending?

A. Yes, indeed. All the peasants and working men went to the fight consciously. We didn’t even have to call a meeting; we just had to announce that there was an uprising of the Semionoffs, and they all knew what that meant.

Q. How many people do you suppose there were who were opposed to the Soviets before the Allies came?

A. You mean in Habarovsk? Well, you see that city is really an officers’ city. It was the capital always of the Far East, and all the officials and all the banks and many governmental institutions were there, and, of course, all these officers were against it. Out of 50,000, perhaps, five or six thousand would be against the Soviet. All the higher officials were in the beginning against it. They would try to sabotage. Banks would go out on strikes. The higher teachers, too, went out on strike, but the parents called meetings and compelled them to go back and teach their children. We declared that if they did not go back they would have to go to work in the shops, and so they went back.

Q. Do you think that there was a higher percentage of people against the Soviets there than there was in other cities?

A. Oh, yes, because it is an officers’ city.

Q. How close connection did you have with the government at Petrograd and Moscow?

A. In the beginning all the decrees that they had in Russia we had in Siberia, and telegrams came every week. My husband once spoke on the long-distance phone to Lenine in Moscow. But later, about four months before the Allies came, we didn’t have any communication whatever with Russia, and we didn’t know whether the Soviets there were dead or what had happened. We had to work independently. We issued our own money in the Far East.

Q. Is there a bitterer feeling against the Allies than against their own reactionaries in Russia?

A. It is the same feeling; they feel that it is just one company. They don’t discriminate between them.

Q. They haven’t any admiration for Mr. Wilson there, have they?

A. Well, they heard of Mr. Wilson, and they had faith in him, and really the people in Siberia thought that the Americans would not send in their troops. They hoped and believed that the Americans would not send in troops, and they were surprised when they did, I was surprised, too.

Q. How did you manage to get away?’

A. I got a passport under a false name and went to Yokohama. While I was there I bought a copy of the Japanese Advertiser, published in English, and I found there a paragraph about my husband. I will read it to you.

“The most important personage in Siberia at present is Krasnochokov, the leader of the Siberian Bolsheviks. No one now knows his whereabouts, but he is really an admirably strong man, while being in possession of a large sum of money with which he can easily start disturbances in either Mongolia or Manchuria. Four of his colleagues are now imprisoned in Vladivostok, and the allied authorities are exerting themselves for the arrest of Krasnochokov. He may, perhaps, have the intention to go to America.”

That makes me hope that my husband was not executed, after all. But, of course, I do not know. If he is alive he will communicate with me as soon as he can.

Q. After the revolution did the people think that they had to work less?

A. In many cases they worked harder, not because they were compelled but because they saw the necessity for it. Now, for instance, the sailors in Chabarovsk. It was in April, 1918, when the ice on the Amur cracked and the sailors had to prepare the boats for the navigation. The commissars and leaders at first doubted as to the faith of the sailors. But to their greatest surprise, when the day of navigation came, the fleet on the Amur River came out in its full beauty, every boat newly painted. With red flags on each boat they floated, covering the Amur. They were ready for the summer work.

I also remember the time when we could not obtain money from Petrograd because Semyonoff stood between. The railroad men worked for three months without getting wages. They knew that the Soviet had no money to give them and were willing to work without compensation.

Q. Why were the people against the Constituent Assembly?

A. Well, I think because they didn’t have confidence in the intellectuals. They were afraid to have those former lawyers and all those shrewd people go to Petrograd and put down iron laws for them. They felt that the Revolution was too young for that.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses, was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. An essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1919/04/v2n04-apr-1919-liberator-hr.pdf