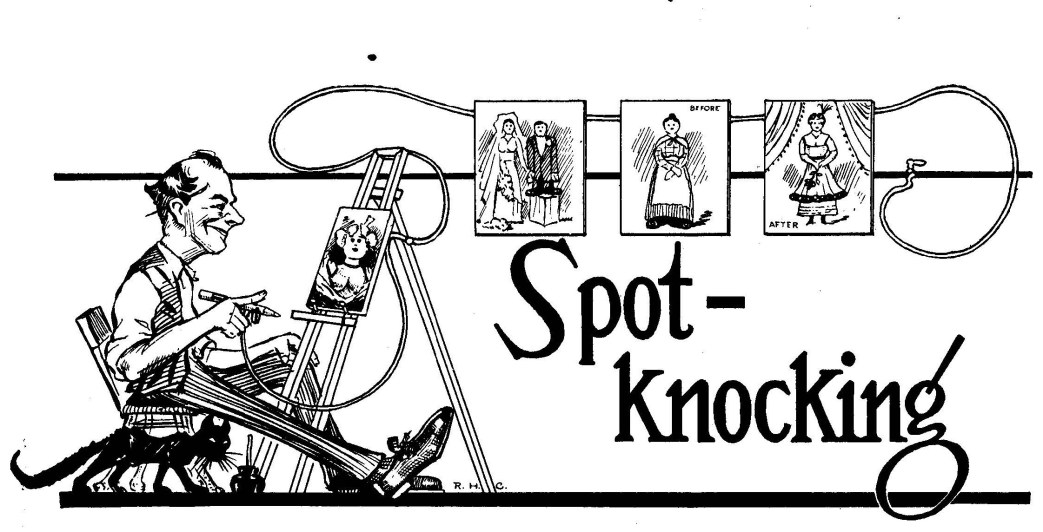

The younger brother of Mary E. Marcy was also a comrade, and a real character as the article below shows. A founding member of the I.W.W., Roscoe (he went by several names) was life-long friends with Ralph Chaplin, sharing a trade along with politics and friendship. Before there was photoshop, there was ‘spot-knocking.’ Both Roscoe and Ralph were masters of the craft, with Roscoe putting his skills to less than legal uses; and doing time for counterfeiting. Below, the process of making the ugly rich and atrocious respectable look good in print. With prohibition in 1920s, Roscoe would run one of Chicago’s most notorious I.W.W. speakeasies.

‘Spot-Knocking’ by Roscoe B. Tobias from International Socialist Review. Vol. 16 No. 6. December, 1915.

SPOT KNOCKER is often a onetime artist, who, because of competition in the original field of his endeavors, is forced to become one of those ill-paid, well-named handlers of the air brush, who take the “spots,” freckles, moles, and birthmarks off the relatives whose enlarged photographs we see hanging dismally upon the walls of our dwellings.

We decorate the small, original, postcard likeness of the barber, in his ten-year-ago style spring suit, with the stripes demanded by this year’s tailor; put gold watches, diamond studs and radiating cuff links on the garb of yesteryear and paint out the too effulgent lines of the fat lady. We place high collars where they ought to be and earn our salt in redressing the dear departed in the fashionable gown decreed by Paris this year.

A “Spot Knocker’s” “lot is not a happy one!” Twenty years ago it was not so bad. My story is the tale of the decline of an artist and the rise of a Spot Knocker. It is the story of nearly all Spot Knockers.

After I had twice taken the first prize at the Chicago Art Institute and had spent a year studying in Paris, and had disposed of less than enough pictures during the ensuing twenty months to pay my room rent, I stepped down from my artistic high horse and solicited work for the magazines, where I was barely able to eke out my vanishing resources for another year.

Like many of my fellow students, Necessity then forced me to further degrade my “artistic gifts” and I attacked the “commercial houses,” which I found also crowded with would-be artists. Competition here was so keen that, in spite of the fact that I was perfectly willing, and even anxious, to draw cut glass ware, or wedge-wood china for half-tone catalogs, at the niggardly sum of $20.00 a week, I soon found myself again in the great Army of Unemployed.

It was then some kind friend came along and told me of that small group of art students who managed to pay their bills by “spot knocking.” Now, in those days “spot knocking” required a certain skill. The worker, aided by a pantograph or an enlarging box—all of this work was made without the air-brush—was hand stippled—actually enlarged the photographs that were brought to him, and some small degree of artistic ability was required to do this work well.

At first I actually enjoyed my work and the unaccustomed affluence that flowed from it. This was long ago and I was very, very young. I took real pleasure in reproducing, in enlarged form, the kindly features, with their wealth of benevolent wrinkles, of the grandmothers. I smiled over the faces of the young women and sweat, good-naturedly, over the innumerable babies. The $50.00 to $75.00 I earned every week brought self-respect, and revived my waning hopes that I might some day become an artist worthy of the name.

But, with me as with many others, the “spot knocker’s studio” became the graveyard of these youthful aspirations. I lived well’ and was known as something of an artist, and still held myself to be somewhat above those menial workmen who labor in grimy machine shops or factories, even after the invention of the air brush. I was still of the artistic world, at least in my own opinion. I was able to swing a “stick,” affect the latest styles in artistic garb and discuss the “arts.”

The solar print was the next step in the production of enlarged photographs. It was a step beyond, or, from the artistic viewpoint, below the period of free hand work. A solar print is a more or less dim impression of the original photograph printed large size on steinbach crayon paper sensitized’ with silver nitrate.

But pride goeth before the “machine,” and so went the last of mine. The bromide process was so perfected that the despised printer could appropriate a portion of our jobs by making these “prints.” These were so clear and strong in tone values that they left very little for us to do. A bromide print is almost as clear as the original photograph—sometimes clearer. They are printed on smooth paper and look just like large photographs.

These we were merely required to “touch up” before delivery.

Our arduous labors, our artistic achievements, now became merely the removing of moles, the insertion of dimples, the straightening of crossed eyes and the invention of jewelry. During the first stage of the innovation we were often required to redress a woman wearing the costume of the vintage of ’89, and set her forth in the latest decoction from some Paris modiste. But here again the mechanics of the printing shop encroached upon the “artistic” domain, and standard forms and plates of modern garments were substituted in rough print for use in the large “hand-painted” portrait.

The Art Institutes have continued to turn out more and more students with the passing years, and competition among Spot Knockers has grown appreciably keener, until today we receive from 15 cents to four bits for each enlargement or each “hand-painted enlarged portrait,” for which the customer pays the studio companies $2.98 to $10.00, “including the frame.”

It was early in my spot knocking career that I discovered that the interests of the order-getting Agents and the Spot Knockers was not always to be considered identical. The Agents often secured their contracts at our expense. They still get many orders by promising impossible results, which we are expected to carry out, orders that may mean much extra work and worry and time and labor to us, for which we receive no additional pay.

I have often noticed the remarkable versatility and imaginative ability possessed by Agents. Whether it is that the job causes these budding talents to blossom, or whether it be that the talents secure the job, I cannot say. But Agents are required to produce the “business,” and their methods are often unique.

Louey Steinheimer, the best order-getter of the Cincinnati Studio, in which I “knocked” for two years, was the best weeper-on-the-job I have ever met. Louey used to copy the addresses of funerals from the daily papers and skip around and wait on the stoop till the mourners came home—waiting for orders. By the time the carriages coming home turned the corner he had loaded up on Uncle John’s or Cousin Eleanor’s—or whoever it was had passed away—characteristics, and was ready to sympathize with the bereaved—and take orders.

He would dwell on their good qualities and gaze upon their features—if he was fortunate enough to secure a photograph—and moan, “Such a man! To lose such a father!” Or “husband” or brother, as the case might demand, and squeeze actual tears from his eyes. Usually he was able to get the whole family wrought up into tears again, and before their eyes were dry enough to see the contract very well, he got his orders. We all voted him the most realistic mourner off the Legitimate. He could turn on the faucet of his emotions like a soda-water clerk serving orders.

Louey’s specialty was among the bereaved. Bud Higgins worked among the foreign working girls and wives of foreign workingmen. Most of these had friends, or sweethearts or relatives in the Old Country to whom they desired to send pictures of themselves. Nine times out of ten these people wished their portraits to represent worldly wealth hoped for, but not yet attained. And Bud Higgins was lavish in promising additions for us to make, diamond necklaces that radiated light like the setting sun, modern gowns, latest coiffeurs, jewelry, gloves, hats and coats to suit, with hosiery and slippers to match.

It was almost as good as a course in designing for us Spot Knockers, but it did not pay. At 50 cents a figure on an enlargement and 55 cents for two heads, etc., etc., the more new clothes we had to paint in, the more jewels we had to sprinkle on, the more heads of hair we had to redress, the fewer pictures we could do per day. We told Bud. We said we were only expected to wash out wrinkles and take off warts and moles and birthmarks and such things. We said we were willing to put on gold watches or diamond stick pins, or rings and even dimples, but we thought some extra charge ought to be made for coloring faded hair, putting heavy growths over bald spots, fat reductions, bust enlargements, Paris gowns and making old folks young and poor clothes fine.

I never heard any one among us object to straightening the limbs of a bowlegged man, nor to inventing a decent amount of jewelry. But when Bud came in with orders to “reduce the young woman,” who weighed 210 pounds to 140 pounds, the most patient, long-suffering Spot Knocker in the studio, Old Baldy, went on strike.

It had reached the point where agents would promise anything to secure orders. One woman insisted that we make a small postcard front view picture of her husband over into an enlarged “side view.” A Swedish mother asked to have her baby’s picture “made a year older,” because the photograph had been taken at one year and the child had died when it was two years old.

For a long time we endured, uncertain how to voice our rebellion. We did not want to throw down our tools and go out on strike because some of us objected to such methods. We had not yet learned that the Spot Knocker’s job is subject to the same laws as any other job. Besides we knew there were hundreds of hungry’ art students who would flock over and into the studio and take our jobs and hold on to them as tight as a drowning man hangs to a bubble. I don’t like to add that we recalled the time when we had struck and some of our own number had sneaked in to work evenings, thus scabbing on themselves and the rest of us.

It was when things were in this state of sullen rebellion that the Duke came back to the studio. The Duke was Spanish and as full of kick as a young donkey. He had joined the Socialist Party and the I.W.W., and he started right in doing propaganda work among us heathen “wage slaves.”

Times had been dull at the studio, but just then the ante-Christmas orders began to pour in. We all figured that here was where we would roll up a little rainy day money and pay up our bills. Bud Higgins, Weeping Louey and ‘Art Strumsky, who worked the weddings, went on a regular contract-getting debauch. The orders poured in and we all worked over-time and Sundays at 50 cents per figure trying to catch the fish while it rained mackerel.

But orders became more difficult of execution every week. It took the Duke only a day or two to notice that instructions were becoming more and more involved. One day he came to me with two small photographs.

“This,” he said holding up an exceptionally dim, out-of-door, dinky picture of a tall, gawky youth wearing a pale, timid-looking moustache, “this is John, the bridegroom, and this“—pointing to a fat, little brunette with her hair in braids, “this, is the blushing bride. I am requested to unite them in the enlargement, dressing the bride in a modern Fifth avenue wedding gown and show her with her hand upon the groom’s arm. And, this, spindly, spineless creature wants his moustache removed, evening dress put on, with jewelry, white gloves and all the rest of it—all for the paltry sum of fifty-five cents. Here’s where I cure Art Strumsky of his facility in promising stuff that means quadruple work for Sweeney.”

It gave us real pleasure to watch the Duke. He put in a good deal of extra time on that order. He gave the little dumpy bride’s head the wedding gown and the form of the slimsky Consuela, Countess of Rarlborough, and he set the lanky bridegroom’s head upon the shoulders of a short, stout body, working his shoes in at the knees with a board box beneath them. A full sixteen inches between feet and knees were painlessly removed by this artist-surgeon. The whole picture was a “bleacher” (print removed with cyanide). It was beautiful. The fat, merry face of the little bride peered at us atop the slim form of a six-foot society matron, while her hand rested upon the arm of her husband, who had been reduced to a bare four feet. Apparently the bride fairly towered above her lord.

We knew this order would be thrown back upon the hands of Art Strumsky and that he would have to pay the Duke, personally, for the job. It looked like a brilliant way to cut down our labors within reason. We all picked up ideas from the Duke like a lost pup goes after a bone.

That same day Louey came in with two nice orders from widowers whose wives had been laid to rest and who were willing to pay $10,000 to secure an improved portrait to hang in the parlor. Louey had promised both men to present their wives in low-necked evening clothes and to doll them up generally like the Sunday Supplement pictures of Who’s Who in Washington, etc., etc.

The decollete order went to one of the boys and he obeyed instructions to the last paragraph. He thickened Mrs. Parker’s hair; he added curls to Mrs. Mike Mahoney’s locks. He gave them white silk hosiery, toe slippers and abbreviated petticoats, as is the style this year. He made no reduction in their forms, which even their best friends would have been forced to admit were a trifle embonpoint, and he certainly did paint those evening dresses low.

I never saw nicer work. He put a lot of time in on that job. Mrs. Parker’s ankles in the enlarged portrait were a whole lot better than they were in real life. She wore shoulder straps to keep her gauze waist up. And Mrs. Mahoney looked like a couple of Schuman-Heinks rolled into one who was trying to break out of her clothes.

Bud Higgins had grown ambitious (in planning extra work for the rest of us) along with Art Strumsky and Louey. They seemed to be trying to out-do each other in seeing which one could plan the most elaborate tout ensemble for us to work over. The Duke said that when Bud was talking-for-an-order he offered as many things as the most expensive beauty doctors, gowns as lovely as Lillian Russell’s, wealth, beauty and a dip in the Fountain of Youth—all at the expense of the poor Spot Knocker.

Those of us who had been executing orders for Bud, grudgingly, grumblingly, peevishly, began to take a new interest in life. We followed Bud’s lavish instructions literally, we retouched, re-dressed, re-formed, revived and beautified each and every photograph out of all semblance to the original. We took Maxine Elliott as the ideal for brunettes and Lillian Langtry as the perfect blonde. We redecorated poor Lizzie Verblotz until her own mother would not have known her. We touched up worn Mrs. Wezerowsky until she looked five years younger than her own daughter. Ample curves we produced by the magic of our heavy brushes, where had been sharp angles ; we reduced the burdens of the fleshweary and a number one A-Last slipper was the largest thing we knew in feminine footwear.

Not a single point of identification did we leave the puzzled Bud. Mary Weiskowniff, with her high bridged little nose re-done into a Lillian Russell, was not to be distinguished from Kathleen Levine, whose retrousse organ had yielded to the perfection of a Maxine Elliott.

The two practical widowers rolled up their sleeves and gave Louey a beating that sent him to the hospital for three days when they saw those “low-necks”; nine out of ten of the Beauty enlargements were thrown back upon Bud’s hands by the enraged contract-signers, who insisted that “that ain’t me” and the bride-and-groom output was an ignominious failure from Art Strumsky’s point of view and a howling success from our own. Little discrepancies in height, weight, etc., etc., had served our purpose, so that our “strike on the job,” as the Duke called it, made good and today we are almost back to the old basis of dimple and jewelry insertions and wart and mole eliminations.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and loyal to the Socialist Party of America. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v16n06-dec-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf