Marxist historian Herman Schlüter (1851-1919) was a correspondent of Engels’ both in Germany and later when Schlüter emigrated to the US in 1889 where he joined the editorial board of the New Yorker Volkszeitung. At first he was a member of the the Socialist Labor Party, later he joined the Socialist Party, which he represented at the Amsterdam Congress of the Second International in 1904. In this chapter from his classic work on brewing in the U.S. he looks at early attempts to form unions by brewery workers after the Civil War and the first large-scale strike in 1881.

‘Beginnings of Organization’ by Hermann Schlüter from The Brewing Industry and the Brewery Workers’ Movement in America. International Union of United Brewery Workmen of America, Cincinnati. 1910.

Beginnings of Organization.

1. THE FIRST ATTEMPTS.

WHILE the development of industry in the United States had given birth to a number of small trade unions as early as the middle of the last century, it was not until the end of the seventies that the brewery workmen began to grasp the idea that in union there is strength and that if they were united they would then be in a position to improve their horrible lot. This was in part due to the inhuman conditions under which the brewery workmen labored, and partly to the special character of the brewing industry.

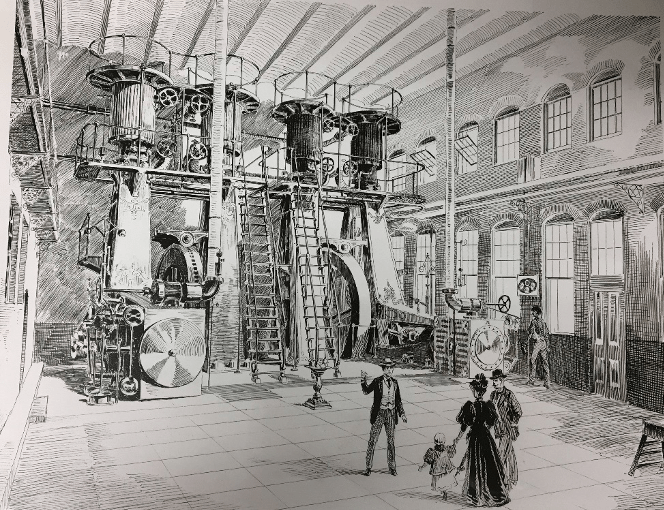

In all industries in which the greater part of the capital invested is constant capital—that is, capital which takes the form of factories, machinery, raw materials, etc., or, in brief, the means of production—the labor movement develops later than in those industries in which the greater part of the capital is variable capital—that is, capital which is used in the purchase of labor-power, in the payment of wages. The reason for this is obvious. In industries employing large numbers of workingmen, just on account of their large number the social distinction between the capitalists and the working class is more quickly perceived by the workingmen. Therefore, in those cases where large numbers of workingmen are employed, regular organizations of workingmen will be formed sooner than in industries employing but few wage-workers.

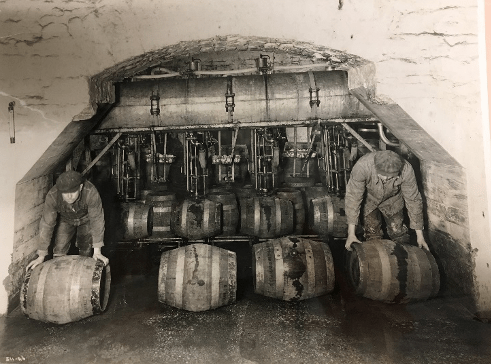

The brewing industry is one of those in which the capital used for the purchase of labor-power plays but a comparatively small part. In comparison with the total capital in use in the brewing industry only a few workingmen are employed. These men, owing to their hard labor and the inhuman conditions under which they worked, did not have much opportunity for organization. About 1870 there were on the average only six workmen for each brewery in the United States, and by 1880 this number had grown only to twelve. There were but a few breweries which employed more than this average number. This fact explains why, in spite of the great development of this industry after the Civil War, the workingmen employed in it were so late in organizing their trade.

Before their organization into trade-unions, however, there were formed here and there some mutual aid societies, which were the fruit of the first realization by the men that they needed union among themselves in order to withstand the storms of life. In Cincinnati, where the brewing industry had acquired some importance in the fifties, such a brewers’ mutual aid society was founded in 1852.

Even earlier than this steps had been taken in St. Louis to gather the German brewers of that city into a kind of union. It is reported from that city, under the date of May 10, 1850, that a mass meeting of German workingmen was held for the purpose of discussing the means to call into being “associations,” a kind of trade organizations according to the ideas of Weitling. A committee was appointed consisting of three members of each of the trades represented in the meeting. Those elected to this committee from the beer brewers were H. Fritz, H. Wagner, and H. Busch. It is not known what came of this first attempt to found a union of brewery workmen on American soil.

In New York about 1860 there arose a brewers’ military company known as “The Original Brewers’ and Coopers’ Guard.” This developed out of the custom of holding an annual picnic accompanied by a parade, which was attended by both brewery owners and brewery workmen, and which took place mostly in Jones’ Woods. Out of this Brewers’ Guard, whose chief personage at this time was J.C. Glaser-Hupfel, there developed the “Original Brewers’ and Coopers’ Sick Benefit and Mutual Aid Association of New York,” which was founded on October 26, 1867, and which still exists. The brewery owner Hupfel, already mentioned, who is even now an honorary member of the organization, was elected its first president. The other officers were Henry Fritz, Fred Gotz, Georg Ringler, Oscar Rocke, and others. Fifty-one members joined the newly-formed society at its first meeting, and twenty-eight more followed at the second meeting.

This brewers’ mutual aid society included employers as well as workingmen in its membership. The exclusive purpose of the organization, which was at first confined to Manhattan Island, was assistance in case of sickness, death, or accident, and it was emphasized that in a country, where those of foreign birth find themselves lonely and friendless and in a clime where sickness brings misfortune and misery into numberless families, it is the duty of every father of a family to make provision for protecting those dependent upon him when he himself is not in a position to earn their daily bread.

No thought was yet given in brewery workmen’s circles at that time to the improvement of the workingmen’s conditions within their trade by means of organization, and the Brewers’ Mutual Aid Association took no steps in that direction, although especially at that time—immediately after the Civil War—the labor movement in America, and more particularly in New York, showed signs of rapid growth.

In August, 1866, a general convention of workingmen was held in Baltimore. As a result of this convention the shortening of the working day to eight hours became the principal demand of the entire organized proletariat of America. From California to Maine the demand for the eight-hour day was so incessantly agitated in all labor meetings that in 1868, just before the Presidential election, the Congress of the United States felt itself compelled to enact that famous Eight-hour Law, which provided that henceforth eight hours should constitute a day’s labor on all government work.

The courts soon put an end to this Eight-hour Law. However, the struggle for the enactment of this law and for its enforcement gave a mighty impetus to the labor movement. When, after the Franco-Prussian War, the German labor movement in New York showed signs of renewed activity, the demand for the eight-hour day again became the battle-cry of all organized workingmen. In 1872 the existing trade-unions formed “eight-hour leagues” for the express purpose of carrying on a propaganda for the shortening of the working day. The labor movement became so lively that both the Republican and the Democratic parties embodied eight-hour planks in their respective platforms. In May, 1872, there broke out a general strike of the workmen in the building trades in New York City, which was the beginning of the greatest struggle between capital and labor that has ever taken place in that city. No less than one hundred thousand men left their work.

It was these struggles that for the first time aroused the brewery workers of New York against the intolerable oppression under which they suffered.

A meeting of brewery workmen was called. Shorter working hours and higher wages were demanded, and resolutions were passed to that effect. It was only a handful of men in whom class consciousness thus stirred for the first time and led them to resolve to struggle for an improvement of their conditions. They decided to go from one brewery to another, and on one of the following days they took up their march and presented their demands at every brewery in turn. At the same time the workingmen in the various breweries* were approached and urged to join in the movement, which most of them did. Their demands, however, were refused by all the brewery owners, whereupon the men laid down their work. This was the first time that a strike of brewery workers was undertaken on American soil. Demonstrations and processions were held by the men. On Thirty-eighth street it came to a fight between the police and the strikers when the police tried to break up the brewery workers’ procession by the most brutal use of their clubs. The strike was lost. It could not well be otherwise, as the men had no real organization. Many of the strikers, and especially of their leaders, were kept out of the breweries for a long time, the brewery owners everywhere refusing them employment. Thus was the first wave of the brewery workmen’s movement dashed to pieces against the power of the brewery capitalists.

The condition of the workmen remained for the present unchanged. To toil from earliest morn till late at night, and to drink so as to keep up their strength—that was the daily routine of the brewery workmen. And along with this a scale of wages which contrasted with the wages of other workingmen in the same way as the eighteen-hour workday of the brewery workmen contrasted with the legal eight-hour day. The crisis of 1873 and the widespread unemployment which resulted from it made conditions worse than ever and excluded every thought of resistance. When in 1877 the American working class again began to grow uneasy, and when the great strike of the railroad workers led to general struggles and disturbances, the brewery owners, probably recalling to mind the strike of their own slaves in the year 1872, decided to give a few crumbs from their wealth to the men who produced all their riches. The wages of the brewery workmen were increased from $40 and $45 to $50 and $52 a month. In this way the strike of 1872, though lost, yet did lead, after half a decade, to an improvement in the condition of those who were at first defeated.

In the labor movement even the lost battles bring progress for the fighters.

2. THE FIRST BREWERY WORKMEN’S UNIONS.

The general growth of the labor movement after the troubles of 1877 led, as we have seen, to a small increase of wages in the brewing industry in New York. It did not, however, have a strong enough effect to bring about the organization of the workingmen in that industry.

Such was not the case in Cincinnati, and it was there that the first brewery workmen’s union was called into existence.

As a result of the railroad workers’ strike in 1877, a certain excitement took hold of the brewery workmen of Cincinnati. They came to realize more and more fully that the wretched condition of the brewery workmen could be brought to an end only if they organized and by a united struggle for their own interests won from the brewery capitalists improved working conditions and treatment fit for human beings. So great, however, was their dependence upon the brewery owners and the difficulties in their way, that it was not until 1879 that they at last succeeded in forming an organization, after the failure of efforts toward that end in 1877 and 1878.

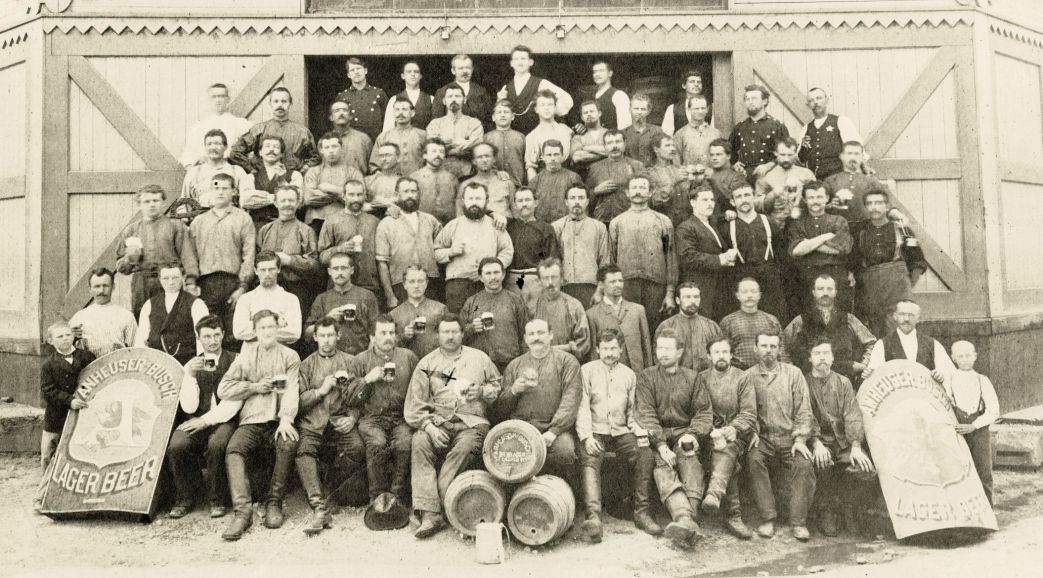

The first brewery workmen’s union was born in Cincinnati on December 26, 1879. It was called the “Brauer Gesellen Union,” and its president was John Alexander. The other officers were Ch. Schley, Julius Zorn, Fritz Bayer, and Hugo Framann.

The young organization affiliated itself with the general labor movement by electing delegates to what was then the central labor body of Cincinnati, the Central Trades Assembly. Rapid progress was made, and within a short time the greater part of the men employed in the breweries of Cincinnati had joined the organization.

In the spring of 1881 it was decided that no brewery in Cincinnati should be considered a union establishment unless at least half of the men employed in it belonged to the union. As a result of the strength which the union gained through this procedure, it was decided in July of the same year to approach the brewery owners for the first time with general demands.

The demands presented were the following: 1. A reduction of the workday from thirteen hours to ten and a half hours; 2. A minimum wage of $60 a month; 3. Permission for the workmen to get board and lodging wherever they pleased, so that they should not be compelled to board with the confidential agents of the brewery owners, the so-called “soul-sellers”; and 4. A reduction of Sunday work from eight to four hours.

Four of the breweries immediately granted these demands. Work was suspended in the other nineteen breweries, and at the same time a boycott was declared on all non-union beer. A few of the smaller breweries gave in, but the power of the larger brewery owners was at last able to defeat the success already achieved. Notwithstanding the support given by the organized workingmen, the struggle was dragged out, and finally a compromise settlement proposed to the brewery owners was rejected by them. The strike was lost and the union lost a large proportion of its membership. Nevertheless, the struggle had its effect. Soon afterwards the brewery owners reduced the working hours, both for weekdays and for Sundays. It took several years, of course, before the union recovered from the consequences of its defeat in this battle.

At the same time, in July, 1881, a struggle began on the part of the unorganized brewery workmen in St. Louis, but it was without result and did not lead to the organization of the workers. It was otherwise in the city of New York, where in that same year the first attempts were made to unite the brewery workmen. Although these efforts did not lead to a permanent organization, they were of value because of the experience which the workingmen gained through them, and because they were made in the chief seat of the brewing industry, where it had already assumed a strongly capitalistic character. The lessons gained during these first attempts of the New York brewery workers proved valuable later when the organization became permanent.

On January 7, 1881, an accident took place in Peter Dodger’s brewery in New York, in which four workmen lost their lives. This was a fire which started during the varnishing of a cask, in which the commonest precautions for safety had not been observed. The workmen who perished in it were A. Witscherock, J. Fanner, John Beierle, and John Braun. The coroner’s jury who investigated the matter censured the foreman of the Doelger brewery, one Peter Buckel, and declared that the whole management of the brewery had been lax. In the course of the investigation it developed that the foreman was in the habit of whipping the men under him. The foreman, on the other hand, pointed out the condition of the workmen owing to their excessive indulgence in beer. These revelations attracted much attention, which was increased by the fact that further accidents happened in different breweries. In the New Yorker Volkszeitung, the organ of the German workingmen of New York, numerous communications appeared, pointing out the evils existing in the breweries, while the entire bourgeois press systematically suppressed all that would throw light on these evils. On February 23, in addition to the previous contributions, “A Few Brewery Workmen” sent in an appeal in which they advocated the union of all the workers in the trade. The men employed in the Henry Elias Brewing Company were especially active in the organization of their trade. They distributed circulars in all the breweries of the city, advocating the founding of an organization. A brewers’ meeting was called for Sunday, March 6, 1881, to take place in Wendel’s Assembly Rooms. At this meeting, which was presided over by Phil. Schottgen and whose secretary was John Buhl, the first “Brewery Workmen’s Union of New York and Vicinity” was started. George Block, who was then active on the Volkszeitung, F. Hartung, B. Kaufmann, and others presented the necessity for organization. One hundred and twenty-one members immediately joined, and an executive committee of seven men was elected, who undertook the direction of the union.

This organization of the brewery workmen proposed, according to its constitution, to improve the condition of workers in the brewery trade and to enlighten them as to the rights and duties of the labor movement. The support of members when in need and in case of sickness or accident and the support of widows and orphans of deceased members was also among its purposes. Maltsters could become members of the brewery workmen’s union only if they were at the same time brewers.

The new labor organization was for the present a great success. Within two months after its foundation, the union counted among its members all the brewers of New York (Manhattan), Brooklyn, Morrisania, Union Hill, Staten Island, and Newark, in as many distinct sections. The brewery owners, through their action, contributed not a little toward this rapid spread of the organization of their workmen. Immediately after the foundation of the union, in the breweries of J. Ruppert, Ringler, and F. & M. Schafer, several officials and members of the union were discharged on account of their connection with the organization. The Volkszeitung naturally brought this matter to the attention of the various labor organizations, whose members constituted the best customers of the breweries in question, and these organizations stood bravely on the side of the brewery workers. The Piano Makers’ Union, an organization which at this time was particularly strong and militant, and the Carpenters and Joiners, also the German Cigar Makers, led the boycott against the beer of those breweries in which the union workmen had been thrown out. This was done in such an effective way that the owners of these breweries soon gave in. The union was recognized and the discharged workers were reinstated. The first victory of the organized brewery workers had been gained. Unfortunately, however, it was not far-reaching nor of long duration. The newly united workers began to overestimate their strength and threw themselves into further struggles for which they were not yet strong enough, and this brought destruction to the young organization.

3. THE STRIKE OF 1881.

The success which the Brewery Workers’ Union had achieved in resisting the disciplinary measures on the part of the Ruppert, Ringler, and Schafer firms, led to the opinion that the young organization was fit to enter further and more difficult struggles, and the idea gained headway that the time had come when it would be possible through a general struggle to improve the condition of the brewery workmen at one stroke.

The experienced representatives of the German trades in New York advised against rash action. They pointed out the youth of the organization, the lack of experience on the part of its members, and also their lack of knowledge in regard to the labor movement; they further pointed out that not all branches of the brewing trade had been organized, and that therefore danger threatened from the unorganized branches. The warnings were in vain. The brewers had recognized their disgraceful condition; they felt as they had never felt before the terrible oppression which the brewery owners exercised over them; and they decided, with more courage than prudence, to venture a general fight. The following demands were submitted: A twelve-hour day on weekdays, inclusive of two hours for meals, and a two-hour day on Sundays, for which they were to be paid 50 cents an hour. In May these demands were presented to the brewery capitalists. Only a few small breweries which were dependent upon the organized workingmen for custom, and therefore could not risk a fight, acceded to the demands of their workmen. The majority of the brewery owners, however, and especially the large brewers rejected the demands peremptorily.

The Brewery Workers’ Union now decided, in spite of renewed warnings on the part of its friends of the other trades, to take up the fight and to declare a general stoppage of work in the entire brewing industry of New York and the vicinity. It was on Whit-Monday, June 6, 1881, that the decision to declare the strike went into effect.

But the suspension of work was not general. In the largest brewery of the city, George Ehret’s, only a part of the brewery workers had joined the strike; the others had remained at work. In addition to this, the beer-wagon drivers, who up to then had not been organized, everywhere took the places of striking brewery workmen, and under the guidance of the brewmasters and foremen, they performed the work of the brewers. Although the central body of the workingmen of New York, the Central Labor Union, declared a boycott against all beer which had not been made by union workmen, and although the Central Committee of the Socialist Labor Party, which was then located in New York, was on the side of the striking workmen with a similar resolution—resolutions which the members of the organization lived up to as far as possible—a long period of bad weather injured the strikers’ cause very much, because there was a small consumption of beer and little demand for it. The strike dragged itself out for five weeks, and then the Brewery Workers’ Union was compelled to allow its members to look for work wherever they could find it. The strike was lost. The masters had triumphed over the men.

The Brewery Workers’ Union had lost the larger part of its membership during this struggle, because the brewery owners would not give work to anyone who had even the remotest connection with the trade-union. Whoever applied for work had to submit proof that he was no longer a member of the organization. The active members of the union, and especially its officials, were put on the blacklist and could get work nowhere, or only where they were not known. Many had to leave New York and its vicinity. Under these circumstances, the continuance of the union was out of the question. It went down, destroyed by the superior power of the brewery capitalists and by the abuse of the economic power which they possessed.

Nevertheless, this lost strike also brought the defeated ones certain advantages. The brewery capitalists recognized that it was not well to draw the bow to the breaking point, and that they must especially take into consideration the mass of organized workingmen, who constituted the best customers for their product. In short, in the course of the summer which followed the strike, several of the larger breweries in New York introduced the twelve-hour day and diminished Sunday work. By so doing they really acceded to the demands of the striking workers. They had not, in fact, cared enough about these demands to fight over them, but their purpose had been to destroy the very troublesome organization of their workmen, the trade-union. When they had succeeded in this, they were willing to grant what had been demanded. The fact that their workmen had organized in order to deal with the brewery capitalists on an equal footing and to force them to improve their conditions was what had called out the wrath of these gentlemen, and had induced them to use all their might in order to bring this organization of their men to an end. The brewery-owning gentlemen did not know that the labor movement was a necessary consequence of the development of industry, and especially of their own industry ; that if it were once destroyed it must yet again raise its head; that the conditions which the capitalistic development of a trade brings with it for the workingmen of that trade must drive the workers to resistance—first to unorganized, then to organized resistance; and that, when this cannot be done openly, when the brutal power of the owners makes the striving of the workers for the betterment of their condition impossible in public, then secret organizations will be formed, and underhandedly and without the knowledge of the employers a fight against capital will be undertaken.

This showed itself, as we shall see, in the brewery industry of our country.

The brewery workers employed by one of the firms of New York, the Kuntz Brewery, resolved after the defeat and destruction of the Brewery Workers’ Union, to form a secret organization. They formed an assembly and joined the Order of the Knights of Labor—without, however, being able to be active. The organization existed only for about a year, and was then dissolved.

For the present, then, every organization of the brewery workers of New York and the vicinity had been destroyed.

PDF of full book: https://books.google.com/books/download/The_Brewing_Industry_and_the_Brewery_Wor.pdf?id=jTGC_SB962oC&output=pdf