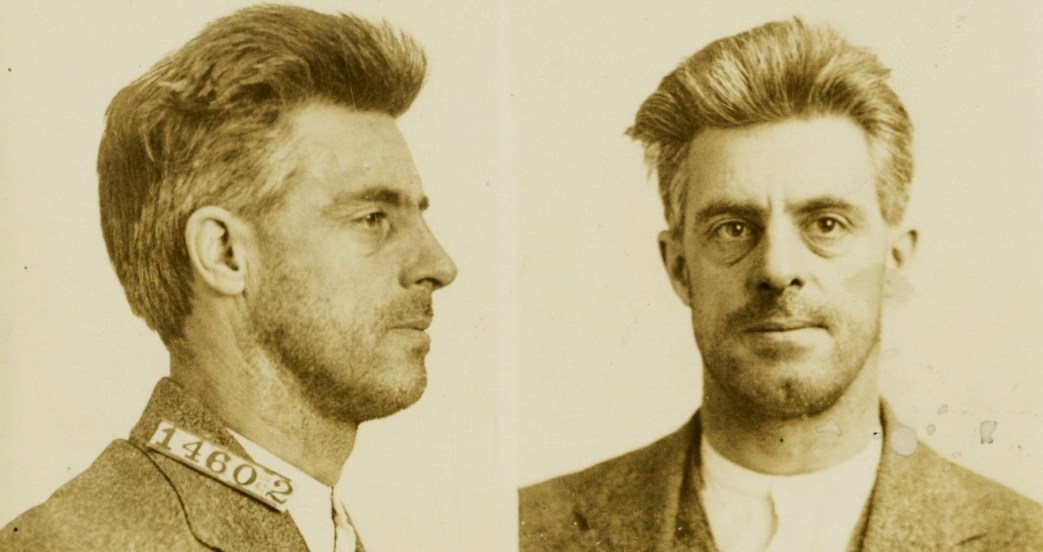

A major figure in Socialist and working class activism in Washington State for decades. Wells was among the best known Socialists in the region, running for Mayor of Seattle in 1912, elected President of of Seattle’s Central Labor Council in 1915, convicted of for sedition for opposing the War in 1917, imprisoned and tortured on McNeil Island and later Leavenworth. On his release from in 1920 he aligned himself with the new Communist movement and was elected delegate to the first congress of the Red International of Labor Unions from the Seattle Labor Council. This is a report to comrades back home on his journey to Red Russia.

‘Through Latvia into Red Russia’ by Hulet M. Wells from The Toiler. No. 185. August 20, 1921.

Delegate of the Seattle Central Labor Council to the Red Trade Union Congress at Moscow, July, 1921.

How long can a big city maintain a show of pomp and ease without visible means of support? That is the thought that strikes one most forcibly after a rough appraisal of the city of Riga. Riga is a large, modern looking city, with broad streets, shady squares and handsome buildings. The only thing that makes it strikingly different from an American city is the scarcity of vehicle traffic in the business district and the presence of the ubiquitous droschky driver with his matted whiskers and flea-bitten little nag.

To come from Libau to Riga is like coming out of the old world into the new. Libau is the principal city of Courland, one of the three districts that make up the state of Latvia. The other districts are Latgale, a purely agricultural section, and Livonia, which dominates the little country with Riga as the capital.

It is in Libau that the misery of the people is most apparent, though there is, of course, plenty of it elsewhere. But there the ragged wretchedness of the poor, and the constant begging of the sad-faced children permit no illusion of prosperity. In Riga the crowds of well-dressed people on the main streets create a certain measure of such an illusion. There are plenty of handsome women in trim shoes and well-cut clothes, and the streets swarm with official and military uniforms. It is a chinovnik city. The system that was scourged out of red Russia finds a refuge here.

I am told by a resident that there can hardly be said to be any industry at all in Riga except the industry of ministering to the official class. Another native of the country says there is much discontent among the farmers of Latgale. It is upon the farmers that the whole burden of keeping up the bureaucratic state falls.

I was able to leave Libau a day ahead of the main body of Russian immigrants who had come on the same ship. These are not allowed to separate, but are shipped over the border as soon as possible, for the Latvian government fears their presence. I hoped by getting away early to avoid some of the discomfort of the miserable service on the Latvian railroads.

I had no such luck, Although I arrived at the depot an hour early it was too late to get a reservation of sufficient space in a compartment in which one may have room enough to sleep. I got a second-class ticket which should have entitled me to a seat. More tickets had been sold, however, than there was corresponding room for, so, after a hard struggle, I landed in a narrow compartment, one of nine passengers with only seven seats, and an all-night trip ahead of us. The locomotives are wood burners. and jog along at about 12 miles an hour with long stops. I didn’t sleep a wink.

Experiences Passport Trouble.

At Riga, after trying three hotels and finding them all full, I finally got a room at the fourth and was preparing to fall into bed when I was requested to show my passport. Now, as I was bound for Russia and was therefore a suspicious person in the eyes of Latvian officials, my passport with those of all the other immigrants had been taken up at Libau and was to be held until we were over the Russian border. So here I was without a place to lay my tired head, for no householder in Latvia dares to take a stranger in unless he has a passport.

So that day I got no sleep, but that night, through the kindness of some Russian friends, I was given a bed and the next day I was herded with about 800 men, women and children into an immigrant train.

The train consisted of freight car of the small, continental type, with a few loose planks to serve as seats. There were about 25 passengers to each car. It was only about 200 versts to the border–a verst is about two-thirds of a mile–but we spent two nights in the cars, and were held another full day a short distance from the border while our baggage was examined.

The nights were very cold, and we had no blankets, so I slept hardly any for three nights. There were two women and a little boy in our car. We made them as comfortable as possible, which was not much, and the rest of us lay curled up on the floor, for there was no room to stretch out. I was half buried under Russian boots and was glad I took my overcoat.

We were under guard of 24 Latvian soldiers, and they had a couple of prostitutes along with them and a collection of booze. One soldier got drunk, and instead of going to his car decided to get into ours. He came climbing in, throwing his gun around recklessly and fell down in a stupor. One of his comrades came in and took away his cartridges, which made him furious when he discovered it. Shouting loud imprecations he fell headlong out of the door. We hoped we had seen the last of him, but eventually he came back and stayed with us, snoring loudly through the night.

Confiscate Goods at Border.

I had no trouble when my baggage was examined, for I had nothing worth stealing, but others did not fare so well. New goods purchased in Latvia are confiscated at the border. That is bad enough, but the law is made a pretext by the officials for stealing goods brought from the United States which have not been registered.

Upon entry into the country we were told that we could register our property. It had nothing to do with customs, as the baggage was in transit. Consequently many immigrants did not understand that the registration was of much importance. I asked what the purpose of it was and understood the answer to be, “In case you lose anything.”

Now, later, at the Russian border, the rascally Latvian officials asserted the right to seize either goods or money that had not been registered. Of course, to search the clothing of more than 800 people, as well as their baggage, would have taken much time, so occasionally they made searches of the clothing of people whom they suspected of having considerable money.

We could not see what was going on, for examination was made of one car at a time, but soon we began to hear stories of losses of money. These stories varied so widely that I finally began to hope they were only rumors, but eventually I verified some of them. We had a train committee elected by the immigrants themselves. One of the committee assured me, when the examination was about half through, that the money losses up to that time amounted to about $8,000. Later I personally met one man who had lost $1,100.

He was Abraham Shmitov, a machinist of Cincinnati, traveling to Moghilev, Russia. He had his money secreted in his underwear and shoes. They took $1,350 and handed him back a little of it, saying they would take $1,000. When he counted what remained he found only $250, which led to the discovery that one official had secreted $100 for his personal benefit.

Propagandists Are Active.

This happened at Zilupe. The place was infested with international spies. Propagandists passed systematically from ear to ear telling us horrible tales of what would happen to us inf soviet Russia. Somebody pays these people, and it is not Latvia.

All of this is what might be expected from a government which in 1919, as I was informed by a Lettish comrade, arrested 29 Latvian boys and girls for belonging to a young people’s socialist society, executed eleven and sent fourteen to prison.

The scenes along the route were very interesting. It was country that had been fought over at different times from the first German advance to the defeat of Yudenitch and his supporters. The land was strewn with barbed wire entanglements, some of which were used for fences. Trenches and earthworks and buildings demolished by shell fire were to be seen frequently. The landscape consists of well-kept farms, broken by stretches of small timber. The fields were green with winter rye, and here and there small orchards were in bloom, I was told that the peasants do not plow the soil deeply enough and the crops often suffer from drouth later in the season. I saw windmills exactly like those of Holland and wellsweeps like old New England.

Many of the women here were barefoot, in some cases very pretty girls, otherwise quite well dressed. The more well-to-do among the city women are extremely well shod. They wear shoes with a round toe and high heel that make their feet look very small. The poorer women in the cities were barefoot and dressed in wretched rags. Our baggage, which filled nine cars, was loaded by old women and young girls, either barefooted or their feet tied up in rags.

Rationing System Essential.

The extreme poverty and wretchedness of the lower class in Latvia well illustrates the distress that must result in a social class system in a time of national extremity. The only alternative in such circumstances is a rationing system such as that of soviet Russia.

As soon as we got to Riga, we began to see the famous Russian institution of the samovar. It is a hot water receptacle built around a little stove, which is fed with chips or charcoal. For outdoor use it has a length of stovepipe. The peasants tried to sell us everything in the way of food, such as bread, cake, milk and eggs, as well as tea from the samovars. Wherever we stopped at a large station, however, the railroad supplied us with boiling water.

At one of the stations there was quite a fraternal demonstration. The townspeople crowded around the cars and talked to the immigrants in friendly fashion. Then after the singing of songs and a display of red flags, the Russians furnished music for an impromptu dance between the railroad tracks, the Russian men dancing with the Latvian girls. This was at the last station before we reached Zilupe, which I have already described. Here, as we were shivering in the chill of the evening, I started a little fire for the benefit of a little group of kindred spirits who had discovered each other en route. Two of us were delegates. Two of us were e political refugees, and one was a girl from the Soviet bureau in New York going to join the rest of Marten’s staff in Moscow. We were just getting comfortable when a soldier came and drove us away.

It was a time of rather tense apprehension for some of the members of the group. We were all glad when the last of us had answered to our names after standing for two hours in the gathering darkness while the passports were called off. In a country where there are so many spies it was not difficult to imagine some apparent comrade turning out to be the agent of some foreign government.

Meets a Bootlegger.

I had little at stake and therefore was not bothered by nerves, but when one of my friends called me aside to tell me of suspicious things that he had noticed, the plot did indeed appear to thicken. As I stumbled along in the dark to find my car, I started, when a Latvian guard grabbed me by the arm and talked to me in an urgent manner. But after calling an interpreter I discovered him to be an innocent bootlegger who desired me to make proper provision before entering dry Russia.

The train started at last, and nothing had happened. Fifteen minutes later it stopped. All of my companions had disappeared except the girl. We wondered what was up. Then my name was called and I slid out of the door and found my three friends and the committee.

“Come along,” they said. “Where?” I asked.

“To Russia,” they answered. “Oh, please don’t leave me,” pleaded the girl, running after us without her hat. So we took her along. We plodded along the side of an embankment, feeling our way in the dark. Then we crept across a trestle that spanned a little stream. And here was an official car, and hearty handclasps and hospitable greetings from fine young comrades in the uniform of the Red Army, and clean beds into which we tumbled for needed sleep–and we were in Red Russia.

Seattle Labor Record.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n185-aug-20-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf