The sixth chapter of Nearing’s 1926 work on Soviet education.

‘VI. Higher Educational Institutions (Colleges, Universities, Institutes)’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

VI. HIGHER EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS.

a. HIGHER TECHNICAL SCHOOLS (COLLEGES).

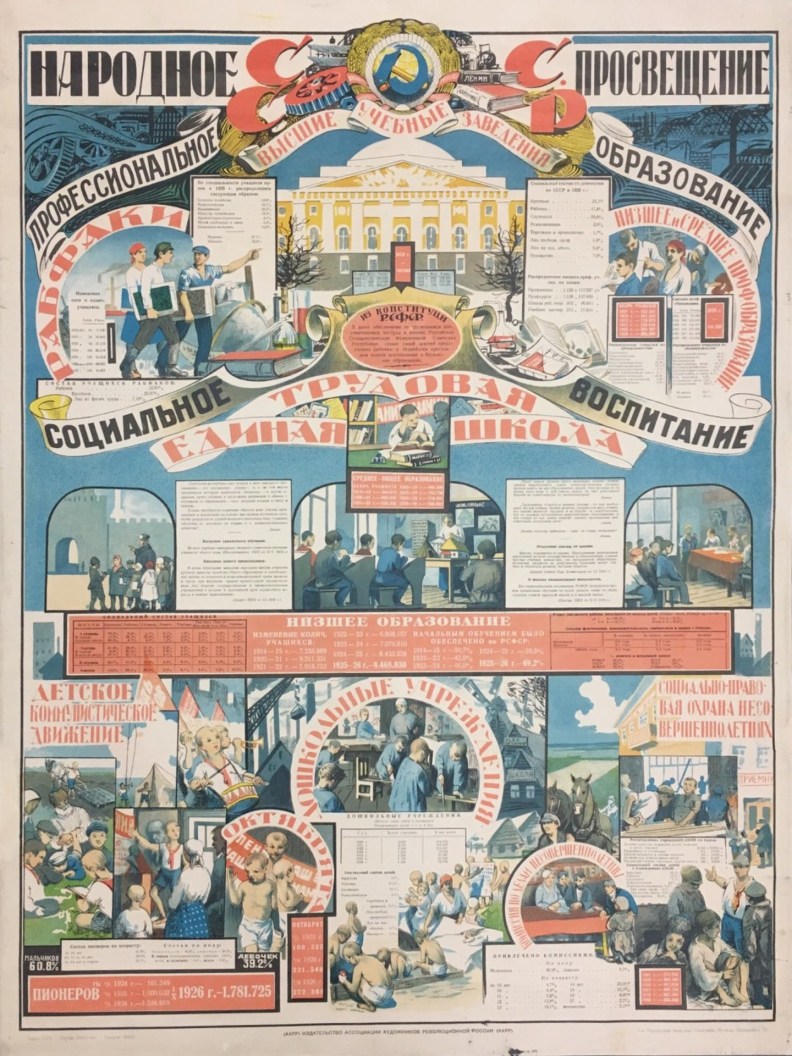

Higher technical schools are the third rung on the Soviet educational ladder. With them must be included the rabfacs, or workers’ faculties that have played so large a part in the history of Soviet technical education. There were 912 of these higher technical schools in the Soviet Union in January, 1924, with a student body of 159,176. Rabfacs numbered 136, with 45,601 students.

Higher technical schools were divided into six main groups: medicine, 66 schools; pedagogy, 331 schools; agriculture, 152 schools; industry, 219 schools; economics and social science, 53 schools; music and art, 92 schools. During my stay in the Soviet Union I had an excellent opportunity to visit a number of these institutions, and to talk with directors, teachers, student officials and students. In many ways, the work being done by these higher technical schools was as interesting as anything that was going on in the Soviet educational world, not because of what is taught, but rather because of the way in which the teaching, and in fact the whole administration of these institutions, is carried on. Physical equipment in the higher technical schools was poor on the whole. Many of the buildings were out of date, and badly in need of repair. As a rule the laboratories were well equipped, and some of the libraries were excellently stocked with books and with current literature from all parts of the world.

“Lecturing” has been gradually abandoned in most of the higher technical schools. All of them were using some form of the laboratory system for their social science as well as for their natural science. On several of them a tutorial system was being tried out. Academic work generally seemed to be on a high level. Everywhere the students meant business.

A brief description of a higher technical school at Stalinov will give some idea of the conditions under which this branch of Soviet education is proceeding. This school is located in the machine-industry and coal centre of the Donetz Basin.

There were about 250 students in the technical school proper, about half of whom were taking work in mining, and the other half in mechanical and electrical engineering. The school provided the educational work, the living quarters and a part of the food which the students needed. It also allowed each student a stipend of twenty-five rubles a month.

An American, accustomed to the atmosphere of the ordinary college campus in New England or in the middle West, has a queer feeling in this institution. He does not get this feeling from the buildings or the equipment, which are much like buildings and equipment in the United States–not so elaborate, perhaps, but almost as up to date. Any American college of three or four hundred students would welcome these low, roomy buildings and this wide campus.

The queer feeling came from the students themselves. They were different.

Stalinov and the surrounding industrial region was entirely in the hands of the workers. It was they who, indirectly through their Government, and directly through their power to appoint students and to act on the governing board of the school, controlled the institution. No student could attend this school unless he came with the recommendation of some organization connected with the labor movement. As a matter of fact, most of the students came with credentials from their trade unions.

Before entering the school a student must have worked at least one year in some productive occupation. During his school vacation he must devote at least two months to practical work in his chosen calling. The Stalinov Technical College was a training school for the directors of working class industry. It was a workers’ college in the most complete sense of that term.

Take, as an illustration, a student who had decided to become a mine technician. He worked at least one year in or about the mine. Then, with a recommendation from the Miners’ Union he applied for admission to the College.

Under certain special circumstances he might be admitted to a training course that was connected with the College, without having completed the work of the lower school. Ordinarily, however, he had passed through an elementary school and a professional school. Having satisfied these requirements, the student was enrolled.

He took the regular work in mathematics, chemistry, metallurgy, history, drawing, etc. In addition, he and two or three of his fellow-students were assigned to one of the mines in the neighborhood. In this mine they spend at least one day in each week, and present a weekly report on the mine. During the summer they spend at least two months at this mine, and prepare an annual report on its condition and its operations. Unless, for some reason, they are transferred, these students spend three or four years studying the mine, theoretically and practically. When they have finished their work at the school they spend a year or two in practical mine work. If, by that time, they have demonstrated to the satisfaction of the school authorities and of the mining authorities that they are able to carry on the profession of mining engineer, they are given certificates of proficiency.

The student who enters this school has another experience of quite a different sort in store. When he is accepted by the institution as a member of the student body he becomes a member of a self-governing commonwealth. The students are represented on all faculties in the proportion of one student to two teachers; they participate in the administration of the institution; they are in complete control of student discipline; they control, through student committees, the housing and feeding of students, and the purchase and distribution of supplies. In every sense, academic and administrative, they are a part of the institution in which they are doing their work.

Probably that is the chief reason why these students are different from American students. Both in their studies and in their college activities they are, in large part, the masters of their own affairs. Already, while in college, they are going about the business of life.

Stalinov students are, on the average, only a very little older than American college students. But among them all there is not a single gentleman’s son, and, so far as one may judge, not one who expects to become the father of gentlemen. They are workers. They belong to the unions that recommended them. Seventy per cent of them are Communists. They have turned their faces away from the past, and are building a new society.

Life is a struggle in the Stalinov College. The beds in the big dormitory have straw mattresses resting on boards. The food is plentiful, but very plain. It is served on board tables and eaten from wooden benches. There are few of the comforts and none of the luxuries of life. Still, students and professors alike step out buoyantly. They have entered, together, on a great adventure. Life has a meaning for them.

Evening work in a similar school was going on in Kharkov, capital of the Ukraine. There the students came five nights a week, from six until ten o’clock. The course lasted four years. There were 436 men and 6 women in this school. Most of the students were taking work in mechanical or electrical engineering. No one could enter the school without the recommendation of his trade union. Those who complete the course are trained mechanical specialists.

All of the students in this Kharkov school were organized in their respective unions. In addition there was an organization of all the students in the school, with an executive committee, responsible for the conduct of student affairs. The teachers in the school had a similar organization. Both of these organizations were represented on a pedagogical committee that was responsible for the methods of instruction. The committee consisted of seven teachers and three students.

Some of the best class room work that I saw in the Soviet Union was being done in this Profintern Technical School. Every class room was a laboratory. This was as true of social science as it was of chemistry. There were tables (or benches) in these rooms, and the students were at work in groups around the tables. There was not a single class room with rows of seats, screwed to the floor.

I entered a number of the class rooms unannounced. In none of them did I find the teacher in evidence. Usually he was sitting at a table with one of the student groups. Lectures by the teacher and formal class room instruction seemed to have disappeared completely, leaving the students and teachers working together on common problems.

As an instance, the class in mechanical drawing was studying the ellipse. The instructor had distributed to each of the students a piece of pipe, a mechanical tool or a piece of machinery on which an ellipse appeared. In each case the students were measuring and computing the ellipse and then making a drawing of the piece of metal on which they were working. Not once in the school did I encounter such a thing as a “class exercise.”

One left this school with a feeling that it belonged, not to the board of education or to the state, but that it was a joint meeting place for students and teachers, all bent on working out the same problems.

Across the Caucasus, in Tiflis, I visited an interesting higher technical school in which there were 708 agricultural students and 807 students in technology (1,228 men and 287 women). Before the Revolution there were no higher technical schools in Tiflis, but only the Georgian University, conducted in the Georgian language. Students from business-class families pay tuition in this institution. About six-sevenths of the students were on the free list.

There was a general school committee in control of the school, consisting of 120 teachers, 40 representatives of the students and five representatives of the trade unions. This general committee was supposed to meet three times a year.

The main divisions of the school, agriculture and technology, also had their group committees, consisting of the professors, and one-quarter as many students. The group committees met monthly.

Student organization began with the trade union. Each student in the institution belonged to the trade union corresponding to the line of his specialty. It was from these occupational groups that students were elected to the governing committees of the school.

Tiflis lies across the Caucasus from Moscow. Georgia is a remote, and in many senses, an alien country, yet the essential characteristics of the higher education in the Transcaucasian Federation were the same as those of the Russian Federation. Readers will conclude, hastily, that this was the result of pressure from Moscow. How then explain the enthusiasm with which teachers and students alike were taking hold of the new system? The real answer seems to be that workers’ control of educational institutions is a logical phase in the development of a workers’ republic. When the republic reaches this phase, the educational institutions follow as a matter of course.

Near Moscow there is an agricultural and mechanical college with a student body of about 2,900. It is called the Timiriazev Agricultural Academy.

This Academy, originally opened in 1861, has had a checkered career. It was closed by the Government in 1894 because of the political demonstrations made by the students. At the present moment it is probably the most important agricultural school in the Soviet Union.

Timiriazev has three chief departments: agronomy, agricultural engineering and agricultural economics. It aims to train directors for the Soviet Government farms, local agricultural experts and workers to take charge of agricultural co-operatives. The course covers four years.

Lecturing has been abandoned in this institution. As one of the deans put the matter: “We no longer have examination accidents. Students work in small groups under supervision. They are judged on what they accomplish from day to day, rather than on the old basis of a final examination.”

“Subject commissions” were very fully worked out in this institution. A subject commission is a joint committee of faculty members and students which is responsible for planning the academic work of a course. In the Academy there were twelve subject commissions: five in the department of agronomy; four in the department of agricultural engineering, and three in the department of agricultural economics. In the last of these three departments the three subject commissions dealt with: the organization of agriculture; the organization of farming; agricultural co-operation.

Each subject commission consisted of all the teachers who worked in the department, together with one-half as many students. The largest subject commission, in plant cultivation, had 54 members,–36 faculty members and 18 student members. The smallest subject commission had 22 members. The students on each subject commission were selected by the students in that department.

Subject commissions met at least once in each fortnight. They were responsible for carrying out the academic program in their respective departments. When the plans for a new course were first made, they went to the subject commission for its approval. As the course developed, its direction was determined by the subject commission.

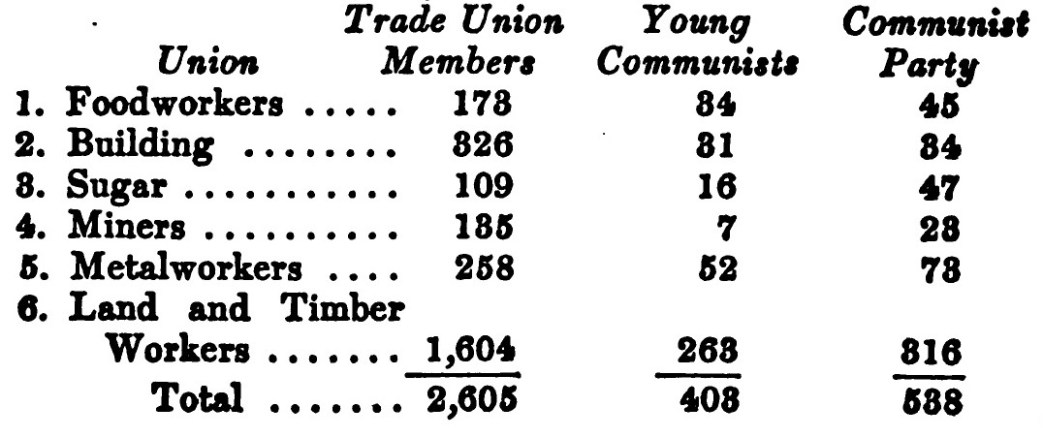

Student organization in this institution was very thorough. Six student trade union groups formed the basis for student activity.

Among the 2,900 students of the Academy about 300 were not members of trade unions. Most of these students were non-wage workers from the villages.

Each one of the student trade union groups has its organization, directed by an executive committee varying with the size of the group. The Land and Forest Workers had a committee of 14. All the others except the building workers had committees of 5. The Building Workers had a committee of 9. All six executive committees had an aggregate of 43 members.

Every six months the students of the Academy meeting in their trade union groups elected a Delegate Body—one delegate for each ten students. This made a total of 260 delegates.

The student general committee consisted of the 43 executive committee members, from the six trade union groups, and the 260 delegates elected to the Delegate Body. This student general committee met every three months, and at its first meeting elected an executive committee of eleven members.

There were four sub-committees under the direction of the student executive committee: (1) The economic, which had charge of providing for the material wants of the students. (2) The committee on club work, which had general supervision over the social life and activities among the students. (3) The academic committee, which worked on the scientific program, and considered questions of method in academic work. (4) The organizing committee, whose business it was to see that the students got into one or another of the student organizations. All forms of student activity were thus centered in the hands of an elected student committee.

Some money came to the student executive from the publishing activities in which it was engaged. The trade unions also provided money for needy students. These sums were handled through the student committees.

The president of the student executive committee, with whom I had a long talk, and who had all of this information at his finger-tips, gave a great deal of time to the direction of student activities. Other members of the executive committee were also frequently called upon to do committee work. For this work in connection with student affairs, the members of the executive committee received from 20 to 40 rubles per month, depending on the amount of time that they were called on to devote to the student activities.

My visit to the Communist Pedagogical Institute in Moscow was very impressive. I was received by a committee of four persons–two members of the faculty and two members of the student body. I went to this school to ask about methods in pedagogy, and my talk with the committee was quite satisfactory. We discussed the success attending the various teaching methods that were being used in the Soviet schools, and I answered a number of questions on American education. Then I turned to the two students with the question:

“Why are you here?”

One replied for both: “All of the students in this school are prospective teachers, therefore they are all members of the Educational Workers’ Union. My colleague represents that organization of the student body. Beside their union membership, the students in this institution are all members, either of the Communist Party or of the Young Communists, as all expect to do Communist educational work. I represent the political organization of the students.”

“Are you two always called in when visitors come to the school?” I asked.

“Of course, we represent the student body.”

The head of the pedagogical department of the school spoke up. “When visitors come here,” said he, “they usually go to the students first, and look us up later on.”

The general school committee consisted of 40 teachers; 25 students, elected by the student body; the president and secretary of the student executive committee, and one representative each from the student trade union group and the student Communist group. The actual administration of the school was in the hands of an executive committee consisting of nine members,–seven teachers, and the two student representatives from the trade union and Communist groups.

There are other kinds of higher technical schools, and there are many other things that might be said about these particular institutions, but I have tried to indicate some of the ways in which they differ most sharply from American institutions of the same grade.

Another group of higher technical schools–the rabfacs–were designed to take care of students coming directly from the factory, and who have had no adequate educational preparation for higher technical work. The rabfacs were created to meet an emergency. They will probably disappear as the emergency passes.

Students in rabfacs are mature people. All of them have worked for their living. Many rabfacs refuse to accept students who have not done at least three years of work in industry.

Rabfacs operate on various bases. In some of them the students do all of their school work by day. In others the students continue on their jobs by day and attend rabfac classes in the late afternoon and evening. Some of the rabfacs combine both of these plans by having the students attend evening classes for a part of the course, and day classes for the remainder.

Whatever the method of school organization, the purpose of the rabfac is the same to take men and women directly from the factories and give them a technical training. Trade unions, or some other branch of the labor movement, pick these students, and in many cases support them during their school course.

The student who showed me through the rabfac at Vladikavkaz had spent several years in the United States as a land and timber worker. In the rabfac he was studying forestry.

“I did my best in the United States,” he said, “but I could never get a chance to start my educational work. Every time I got a little money saved, I lost my job, and nothing ever came of my plans for a college course. I started a correspondence course finally, and just as I got well into it I was deported as an agitator. I left the United States as ignorant as I entered it.”

“Do you agitate here?” I asked him.

“Indeed I do,” he answered. “Every summer I go from village to village and tell the peasants about the new life that is ahead of them if they will just reach out and grasp it. That is one big difference between the United States and the Soviet Union. There I was nearly alone. Here my Union backs me. It helps me to come here to the school and it helps me to carry on this propaganda among the country-folk. A chap really cannot do this kind of thing single handed. It goes much easier when he is backed by an organization. I have found that out by bitter experience.”

We opened the door of one of the classrooms. The teacher paid no attention to us, but one of the students in the class came out at once and asked us what we wanted. We told him, and then I asked: “Why did you get up and come out when we opened the door?”

“I am the chairman of the class committee,” answered he. “It is our business to see that things go smoothly in the class. We take all such responsibility here.”

Every group in the rabfac had such an organization. It was the disciplinary and administrative unit of student life in the Vladikavkaz Rabfac.

This rabfac was a day school. Students came to it from the surrounding towns and from the countryside. It was located in an old newspaper office that had been partly converted into school quarters. There were 150 students, divided into four main subject groups on the laboratory plan. In pedagogy, there were four classes; in technology, one class; in biology, one class. Three-quarters of these students were men; one-quarter were women. Those students who were not sent by trade unions were sent by village soviets. All spent from three to four years in the school.

The students lived in small groups of from three to six. These living quarters were provided and controlled by the students.

School administration was carried on by an executive committee consisting of the director of the school, one representative of the students and one representative of the faculty. The general school committee was made up of the director, six teachers, six students and six representatives of the local trade unions and political organizations.

In the whole region known as North Caucasus, there were nine rabfacs. Seven were day schools and two were evening schools.

Baku–the centre of the oil industry–had five rabfacs. There was one central institution in the city, and four others in the neighboring industrial towns. The central school was particularly well housed and equipped.

There were four rabfacs in Tiflis conducted in four different languages to meet the needs of the Georgian, Armenian, Turkish and Russian workers in the city. In Transcaucasia the language problem is particularly acute because of the great variety of nationalities and dialects. The Soviet authorities are meeting the problem by establishing schools that use the language of the local population. Where there are several languages, as in Tiflis, several schools are established.

The rabfac that I visited in Rostov was a large day school with 680 students. There was a night rabfac in the same building with a student body of 180. A quarter of the day students and a fifth of the evening students were women. Ninety percent of the students in this institution were supported, in whole or in part, by the unions that had sent them there. As a number of these students were mature men with families, the problem of support frequently extended to the family as well as to the student.

All work in the Rostov Rabfac was organized on the laboratory plan. I saw some excellent class work and teaching in this school. The administrative control of the school was in the hands of an executive committee of five: the director, two members of the faculty and two representatives of the students.

Student organization was thorough. The students were organized in their respective unions: metal, land and timber, building, wood-working, railroad, mines, education. The Young Communists also had an organization. There was a general school organization of all the students, with an executive committee of nine, selected for a year, and sub-committees on academic work, co-operation, health, sanitarium care, food, domicile.

Educationally each rabfac represents the organized effort of a picked group of young workers to get a technical training. Economically, each is a self-governing, co-operative group of workers most of whom believe in the practicability of some form of communism, and who, in the course of getting an education, are prepared to practice its simpler precepts.

Students from Soviet professional schools go directly into industry. They have had a preparation designed to make them competent workers. A few, who seem to have unusual qualifications, go on into the higher technical schools, where they receive a training that is designed to make them competent technicians and managers.

b. UNIVERSITIES.

Soviet “universities” are really specialized higher technical schools, each operating in a designated field. Under the Soviet educational system, as it is developing, the university is not the highest stage of the educational structure, and in the old sense of a university as a collection of colleges, the Soviet universities are not universities at all.

There is a bad tradition of university life in the Soviet Union. Like other institutions of the old regime, universities are thought of as parts of a social system that is passing. The old Russian university was designed to meet the needs of the sons and daughters of the aristocracy and of the richer business men. Both classes have practically disappeared from the Soviet Union, and in their places are the peasants and workers, with a different set of educational needs.

The Ukrainian Educational Workers, in a special supplement to their paper, The People’s Teacher (Kharkov, 1925, p. 13), state the matter in this way: “The old ladder of successive steps (primary school, secondary school and higher schools) created by the bourgeoisie,—which distinguished: the school for themselves (the higher school), for their valets and allies (secondary school) and for the people (primary school) does not fit into our system. The limits of instruction are determined by the desired degree of qualification. The mechanical order of succession has been replaced by a succession according to specialization. And just as in industry we have workers ‘of the line,’ and specialists who organize production, the system of public instruction has its mass schools, its schools for specialists and its schools for organizers.”

Prior to the Revolution, the sons and daughters of the ruling class went to the universities, in many cases, for the same reason that many of the sons of well-to-do folks in England and the United States go to the universities—because it was the thing to do. Other young people in their social circle were going and they had little choice.

Soviet social organization has dispensed with this leisure class attitude toward higher education by dispensing with the leisure class. It has thus eliminated that part of the former student body which went to the universities because of the social advantages connected with a university training. The students who are left in the institutions of higher learning are preparing for some specialty.

Beside the sons and daughters of gentlemen, there were two groups of students in the pre-revolutionary universities. One group came for professional training–medicine, engineering. The other group came for advanced work in science, philosophy, or some other field of learning. These two groups are being taken care of, under the Soviet educational system, by institutions that are in many cases wholly separated from the universities. The students who desire professional training go to higher technical schools. The students who are looking for research work go to the institutes.

Such developments deprive the universities of much of their old field. Such developments seem strange, at first sight. When “the elimination of the university from the educational system” was first broached to me by a Soviet educator, I was a little shocked. The idea had never occurred to me. But he explained it in this way:

“Universities in the old sense are really anomalies in the modern world. They originated at a time when the knowledge that was taught in school could all be found in books. There were no laboratories, except the work-rooms of the alchemists, and they were in greater or less disrepute. At such a time it was quite practicable to centre the theological, legal, philosophical and other university courses under one roof, and to have professors and students live and study and talk there together.

“Then there was a period of transition–the period of the introduction of science into the universities. Chemistry and physics, mechanics, geology, biology came, one by one, to take their places beside the old class rooms. In a very real sense, they came to take the places of the old class rooms, since all of the students of specialties were now working in their special laboratories, leaving the strictly class room work for the students of classics.

“Most of the Russian universities were built and equipped during this second period, and as you visit them, you will observe that they have excellent laboratories, and in some cases, exceptionally equipped ones.”

This was true. Some of the equipment in the chemistry and physical departments of the Russian higher schools was as good as anything that I ever saw in an American university.

That second period in the life of modern universities passed very quickly. Before the World War, in Germany, and particularly in the United States, a new type of university work was developing,–in the industries themselves. My informant said:

“It was idle for a university to try maintaining an electrical laboratory side by side with a well-equipped electrical plant. The electrical plant was itself a laboratory, and the theoretical work that it needed was done on its own premises, by its own experts. Sometimes these were university men. More often they were giving their whole time to the work of improving the industry. What folly to duplicate the electrical plant when the students from the university department of electrical engineering could do their practical work in the plant.

“For the last thirty years, in the great industrial centres of the West, universities have been sending their students of mechanics into mechanical plants, just as they sent their students of medicine into hospitals. Specialization, and the very rapid development in various mechanical fields made this inevitable.

“We, here in the Soviet Union, have realized this trend, and we have carried the process one step farther. Since it is impossible to put all of the study and research work into four walls, why try to do it? Since study and research are being carried on in connection with all of the more important institutions, why not have the students go where the study and the research are being carried on?

“If we desire to make an investigation of serums and vaccines, we organize an institute, appoint a staff, provide quarters and have the work carried on under the direction of the health department. A student interested to become a specialist in this field of public health could scarcely do better than become an apprentice in such an institute.

“Every great industrial plant has its department of research and investigation. Students who are interested to pursue that line of inquiry belong there. Of course their work should be directed, just as the work of every apprentice should be directed. But their work-place, as apprentices, is the industry rather than a college campus.

“You began this in the West, with your Pasteur Institutes and Rockefeller Institutes. But they were exceptional. You still cling to the old forms of educational institutions because you still live in the old society. We live in the new society, and we are therefore creating new forms.

“We feel that it is neither possible nor desirable to centre all learning and all research at one point—the university. The learning must be done at the point where the work is being done–mining engineers must study in the mines, and hydraulic engineers in hydraulic plants. We are creating special higher schools at the points where specialized activities are in progress, and our students spend a good share of their time at work in the specialized plants. Since the work of the world cannot all be done at one point, we regard it as unreasonable to suppose that all of the apprenticeship for life’s activities can be centred at one point.”

There are still universities in the Soviet Union, particularly in the old centres of population, but their tone has changed with the changing complexion of the student body. The First University at Moscow has about 9,000 students, organized as in the other higher schools. About 7,000 of them are organized in eight trade union groups: health workers, education workers, chemical workers, land and forest workers, workers in trades, metal workers, miners and railroad workers. Each one of these student unions has its own organization. Each union selects one delegate for every fifteen members. The delegates, meeting together, constitute the student delegate organization, which is in control of all student affairs in the university. Its executive functions are performed by a committee of fifteen, chosen by the delegate body. Seven of the fifteen executive committee members give a large part of their time to the various student activities, and by way of compensation they are paid from 30 to 40 rubles a month.

Every faculty in the University has its program commission consisting of faculty members who give the courses and half as many students, elected by the student body in that particular department. Work is planned, supervised and directed by these program commissions.

About 45 per cent of the students in the First University receive stipends that average 23 rubles a month.

I obtained this information from one of the members of the student executive committee and from representatives of the University administration. The students seemed to play much the same role here that they did in other higher technical schools.

Another university that I visited in Moscow was the University of Eastern Culture, organized directly under the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union. The University aims to “prepare highly trained and skilled Marxists, who can do the work of the Communist Party, and other work that the Party directs.” The University is therefore a part of the organized educational work carried on by the Communist Party.

Students were accepted from all parts of the Soviet Union. Since the work was specialized along the line of Eastern culture, most of the students came from the eastern portions of the Union. They took courses in economics, philosophy, history, social development, political theory and organization, and the like.

Educational method in the University of Eastern Culture was in a stage of transition. Some of the departments were working on the seminary plan, some on the laboratory plan. Under the seminary plan, students were organized in class groups of 25 or 30, each member of the class selected a topic (or had one assigned) and then made a report on it to his seminar. Under the laboratory plan, the students worked in groups on group topics. At the time of my visit, there was no general agreement in the institutions as to which was the better method.

“We are still working on that question of method,” the assistant director of the institution told me.

“We are in an experimental stage, and are trying out a number of different ways of getting our work done. When we are convinced what method is best, we shall adopt it generally in the institution.”

The course is for three years. Students select the department in which they wish to work and they then have their general line of study mapped out by the subject commissions.

Student organization in this institute was different from that in most of the other institutions of higher education that I visited. All of the members of the University teachers, students and technical workers were eligible to join a labor commune. Membership was practically obligatory for the students and optional with the others. The labor commune elected an executive committee of nine members, all of them members of the student body. The members of the faculty might be called in as experts or as advisers, but they were not members of the executive.

Labor commune activities were subdivided into the following departments:

1. Economics, having charge of the clothing, feeding and equipping of the students.

2. Pedagogical and educational,—having charge of the general educational policy, the standards of student work, etc. Its activities were directed by a pedagogical council.

3. Medical and sanitary, having charge of physical culture work, and of the health of the students.

4. A comrade court in which all matters of discipline were handled.

5. An administrative department having charge of the machinery of student organization.

6. A bureau of mutual aid to see that students were properly provided with necessaries.

7. A sub-committee of eight in charge of the care of student families.

Like the students in the Institute of Red Professors, the student body in the University of Eastern Culture was made up of mature people who were convinced that a new social order was possible, and although they represented various nationalistic and racial groups, they were all joined together in a mutual benefit association as an effective demonstration of the way in which peoples from different parts of the world and of different human types could get on together.

While the labor commune in this institution was not giving perfect satisfaction, there seemed to be a general feeling that it was a start in the right direction. Like the organization of the pedagogical department of the institution, student organization was in an experimental stage. The student body, like the faculty, was looking for a better way to achieve the ends that they desired to reach.

Universities, in the old sense of collections of faculties, representing all of the departments of human knowledge, are being rapidly replaced in the Soviet Union. They persist in the older centres, but as the new educational life is organized higher technical schools are being established for each field of knowledge and of activity. These schools are being located at the points where practical contact with the various lines of special activity is most possible,–mine schools near mines; schools of electrical engineering near electrical industries; transport schools at shipping centres, and so on. This specialization of higher education leaves a specialized field for the university. It provides certain forms of training, particularly in the fields of social science, that are needed by highly specialized workers in diplomatic and other fields.

C. INSTITUTES.

Institutes are the fourth rung of the Soviet educational ladder: elementary schools; professional schools; higher technical schools (and universities), institutes. A higher technical school exists to train technicians and managers in some designated field. An institute is a centre of what would be called graduate work in the United States.

Soviet institutes are designed to meet three specific needs: the technical training of the leaders of Soviet economic, political and social activity; the training of teachers for higher technical schools and universities; the study of technical problems in all fields of human knowledge by the laboratory method. For the most part, they are centres of research rather than of teaching.

Soviet authorities create an institute wherever they meet a unit problem. This is true of the social sciences as it is of the natural sciences. At present the institutes of natural science in the Soviet Union outnumber the institutes of social science. The largest single institute in the Republic is the Pavlov Institute at Leningrad, which is carrying on psychological research. With the exception of the Pasteur Institute and the Rockefeller Institute, this is probably the best equipped institution of its kind in the world.

At the time of the 200th anniversary of the Russian Academy of Sciences, in the summer of 1925, a list of the institutes in Moscow was printed. Beside the libraries, museums and galleries of the city, this list included: the State Institute of Electrotechnics; the Central Aero-Hydrodynamic Institute; the Thermotechnical Institute; the Scientific Chemico-Pharmaceutical Institute; the Institute of Biological Physics; the State Scientific Institute of Public Health; the Institute for the Control of Serums and Vaccines; the Institute of the Physiology of Feeding; the Microbiological Institute; the Tropical Institute; the Institute of Sanitation and Hygiene; the Bio-chemical Institute; the Institute of Experimental Biology; the State Institute of Tuberculosis; the State Institute of Social Hygiene, etc. There was undoubtedly some overlapping in the work of these institutes, but the aim was to have each institute deal with a special problem.

While I was in Moscow I had a chance to talk with some of the men and women who were organizing institutes of social science. One such group was working out an Institute of Agrarian Economics under the Department of Agriculture. The Assistant to the Secretary of Agriculture was at the head of this Institute; it had an executive board of seven members, all of whom were experts in agricultural economics. The Institute was founded to make a study of the relations and of the necessary economic adjustments between the life of the rural, agricultural population and of the urban, industrial population.

Economic relations between farmers and city workers are as strained and as unsatisfactory in the Soviet Union as they are in the United States–probably more strained because of the backwardness of Soviet agricultural methods. The two groups work on different economic levels. The farmer uses hand tools and animal power. The city industrial worker uses machine tools and mechanical power. The result is a baffling maladjustment. Nowhere in the world has this difficulty been met. Everywhere it demands a solution. The Institute of Agrarian Economics was organized to study the problem and to find the answer.

A building had been set aside for the use of this Institute, a staff of experts had been appointed; a library was being collected, consisting of books, magazines and documents in Russian and in the principal languages of the West; the chief papers of agricultural economics from all parts of the world were being subscribed for; a plan of study was being outlined, and the work of the Institute was well under way.

During the time that I was in Moscow, this Institute was actually in the make, and I could not help feeling how like a military campaign the whole thing was being handled. The best of equipment and materials; the best men available; plenty of funds–all were put at the disposal of the enterprise. No European king ever entered upon a scheme of conquest with more zest and with more willingness to spend time and money in the attempt. But this was a conquest in the realm of economics,–a scientific conquest, to which the best minds and the surplus wealth of the country were being devoted. It was the scientific organization of man’s effort to subjugate nature and to organize society.

Another institute in the field of social science, somewhat farther advanced in its organization, was the Institute of World Economics and Politics, founded in April, 1925, under the auspices of the Communist Academy.

The purpose of this Institute was to collect and publish information bearing upon the major world economic and political relations. The exact program was being worked out by the staff of the Institute while I was in Moscow.

This Institute was directly under the Communist Academy, which is “the highest organ of scientific investigation in the Republic.” The Council of the Communist Academy had appointed a Director for the Institute, a Secretary and an executive board of scientists who were experts in this general field.

Such was the executive group responsible for the work of the Institute. It was given a large building, renovated and equipped for the purpose. It had secured an initial library of about half a million volumes. The Institute subscribed to 60 daily papers from the principal capitals of the world; to 130 economic and social science journals; to the Babson Statistical Service; to the Harvard Business Service; it had the Bulletins of the United States Federal Reserve Board on file, and much other similar material, that was arranged, cataloged, and accessible.

Up to the time that I left Moscow, the staff of this Institute consisted of only eight experts. Others were under consideration.

Any person wishing to join the staff submitted credentials to the executive board, consisting of the work that the applicant had done in the field of social science–studies made, articles or books published, etc. If they proved satisfactory the applicant was placed on the staff at a salary of from 150 to 200 rubles per month. (The highest officers in the Government received 192 rubles per month; an engineering expert received from 150 rubles to 300 rubles per month.)

The staff outlined the work to be done by each of its members, in connection with a general plan approved by the executive board. Reports were made on this work at Staff meetings. When one unit of research work was completed by a member of the staff, it was submitted for approval to the staff, and if passed by them, to the Executive Committee of the Institute. The work was then published in a monograph, and the writer received a regular fee of 100 rubles for each 16 printed pages of the study.

A journal, Les Annales Internationales, was also published by the Institute. To this journal, the members of the staff and other specialists contributed, and were paid at the rate of 100 rubles per 16 printed pages.

There was no teaching work of any kind connected with this Institute. It carried on only research. Said the Secretary: “We are working out an important series of economic and political problems. That is our subject matter. On the question of method we are trying to devise a plan that will give liberty to scientific workers and elasticity to scientific work, at the same time that it coordinates the activities of those working in the same field, and offers them an outlet for the results of their study. Our Institute is a little republic, studying world social science.”

A third Moscow Institute dealing with problems in the field of social science was the Marx-Engels Institute under the direction of the Marxian economist D. Riazanov. This Institute, organized by the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet Union, was making a collection of the material and literature bearing on Marxian economics and philosophy. At the same time it was planning a complete published collection of all the works of Marx and Engels. A complete edition of the works of Plekhanov, the Russian Marxian scholar, was being issued by the Institute. Twenty volumes of this set had already appeared.

The Institute was well housed, and its quarters were being enlarged. Its library had reached considerable proportions. It had what is probably the finest collection of first editions of Marxian writings that exists anywhere in the world. Its reading room was very well equipped, and stocked with current economic literature from all parts of the world and in all of the chief languages. Experts were at work, in various departments, some natives of the Soviet Union, some natives of other countries, some Communists and some non-Communists,–doing various pieces of research in connection with the publications of the Institute. I have never been in an institution of social science research where the facilities seemed to be better, and where the atmosphere was more scholarly and conducive to good results.

These three institutes that I have briefly described were all devoted exclusively to research. Another institute that I visited in Moscow, the Institute of Red Professors, was a training school for teachers in the more advanced social science institutions and departments.

The Institute of Red Professors specialized in the training of teachers in economics, history, philosophy and political science. Students who were candidates for admission to this Institute presented a thesis on some problem in social science: “Marx and Ricardo,” “American-English Diplomatic Relations,” “The Influence of Foreign Capital in Russia,” were some of the topics discussed. thesis was accepted, the student took four examinations: political economy, philosophy, history of the West, and Russian history. These examinations successfully passed, and the student was ready for his three year course in the Institute.

When I reached the Institute, the Secretary, Maria Dodonova, asked me to wait a few moments, while she sent for one of the students. When he came, she introduced him as the chairman of the student pedagogical committee. “He will answer your questions,” she said.

We three sat together, I asking, the student answering, and occasionally referring to the Secretary for details. Most of the answers he knew, however, and in abundant detail.

Students in the Institute were generally Communists, he told me. All were expected to be able to handle at least two foreign languages. We held this interview in English.

Academic work in the Institute was divided into six groups: political economy; Russian history; history of the West; philosophy; jurisprudence; co-operation. Students picked the groups with which they wished to be connected, and were expected to do two pieces of research work per year during each of the first two years. During the third year each student prepared a thesis, which had to be good enough for publication.

All academic work was done in seminars. There were twelve such seminars in the first year class, twelve in the second year class and six in the third year class. Each seminar selected its own teacher, who might or might not be on the regular faculty of the Institute. This year one of the seminars desired to study the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Since no member of the regular faculty was an authority on this subject, the seminar called in a man from outside the Institute. In such cases the administrative board of the Institute must pass on the qualifications of the desired teacher.

Seminars were small–twelve, fifteen or eighteen persons. Themes were typed and distributed in advance of the session at which they were to be presented. All were specialized and technical. For example, a student who was working in the economic group during the first year was required to cover the theory of wealth and distribution and the history of political economy. During the second year, he worked on money and credit and markets and crises. For his third year’s work he selected a thesis theme.

Each year about thirty per cent of the graduating class was picked by the student organizations, confirmed by the administration of the Institute, and sent for a year of study to some Western country. Expenses were met by the Institute. All students during their residence in the Institute received 130 rubles per month.

Students were therefore in the pay of the Institute. During their three year course, and as a part of their work, they were required: (1) To teach workers in a factory for at least four hours per week throughout the three years. This kept the students in constant touch with the workers. (2) To teach, during their first year, not less than six hours per week, in some elementary school, some factory school or some rabfac. This gave the necessary training in pedagogy. (3) In the second and third years, this teaching must be done in some higher technical school or university. This provided contact with the highest educational work of the Soviet Union. The three year course was therefore a combination of theoretical study and research, with practical pedagogy.

All students belonged, of course, to the Education Workers’ Union, since all were preparing for educational work. They were also organized administratively and pedagogically.

Each of the thirty seminars had a secretary. These thirty secretaries, with one of their number selected as chairman, made up the student administrative body of the Institute.

Students in each of the six general courses (political economy, Russian history, philosophy, etc.) chose a dean. The six deans, with one of their number, selected as chairman, made up the student pedagogical body of the school. The student who was giving me the interview was chairman of the board of deans.

All course outlines and proposals for courses go first to this board of decans, composed entirely of student representatives. If they are acceptable they are passed on to the administrative committee of the Institute for approval. All proposals involving questions of an academic or pedagogical character, whether they come from students or from faculty members, must first receive the sanction of the board of deans.

The administrative body of the Institute consists of the Director, the Secretary, three members of the faculty, and two students,–the chairman of the student administrative body, and the chairman of the board of decans.

Readers who know graduate schools in the leading universities of the United States can imagine the feelings of astonishment with which I confronted such an academic organization. In an American graduate school the faculty is in complete control (except for the veto of the board of trustees); the courses are offered and approved by the faculty, and the students take them or leave them as they like. Here students and faculty were working together, with the students carrying a large share of the responsibility for the academic and administrative work of the institution.

The matter is easily explainable. First, the entire Soviet educational system is on a foundation of administrative and pedagogical self-government. Second, some of the ablest of the younger men and women in the Soviet Union are taking work in these higher educational institutions, and it is their wish that they should carry part of the responsibility for the institutions with which they are connected.

The man who was relating these facts to me in such careful detail was perhaps thirty years of age. As chairman of the student pedagogical organization he knew his business thoroughly.

“Tell me,” I asked, “how you got into this institution?”

“From the army,” said he. “Eighty per cent of the students now in the Institute were in the army during the Civil War.”

“How did you get into the army?”

“I was a student of history when the World War broke out. After the Revolution, for three years, I was a political representative of the Communist Party in the army. Then the Civil War came, and I went into the active service.”

“Why did you leave the army?” I asked.

“My interests do not lie in the field of military activity,” he answered. “As soon as the Civil War was over, I got a leave of absence and came here.”

“What was your position in the army?”

“A commandant,” he answered. (That term is used for all Soviet army officers above the rank of major.)

“How many men did you command?”

“Thirty-six thousand,” he said quite simply.

“Then you were a brigadier general, or something of the sort?”

“As to that I do not know,” he said. “We do not have such distinctions in the Red Army.”

“And now you are studying to be a teacher of economics?”

“Exactly. That is where my real interest lies, and it is in that field that we will do our real work.”

He shook hands and went about his business. I took my leave of the Secretary and came away realizing that when brigadier generals go as students into pedagogical institutions, the standards of institutional life may easily be raised.

Such is the work that was going on in some of the Soviet institutes that I visited. I have described only the institutes in the field of social science. If a representative of the physical sciences could make a study of the institutes covering that field, he might come away with an equally interesting picture. As to that I cannot be sure. I can report only on the field that I know.

Generally speaking, the institutes in the field of natural science are older, larger, and more mature than those in the social science field. They had their beginnings long before the Revolution. The social science institutes were impossible then.

Institutes are organized directly under some department of the government, like the health department, or else they are part of the scientific work carried on by some scientific organization, such as the Academy of Sciences at Lenin- grad or the Communist Academy at Moscow. The latter includes, at present, three institutes, and a number of sections and departments. One of these institutes is the Institute of World Politics and Economics; a second is the Institute of Soviet Laws and the Form of the Soviet State; the third is a Neurological Institute. Among the sections of the Academy there is one on Art and Literature; one on the General Theory of Law and Jurisprudence (this section publishes a law encyclopedia); an Agrarian section, and a section on Scientific Methodology. The Academy is issuing a Soviet Encyclopedia that will appear in about 40 volumes. It also passes on the program of scientific work carried on by all of its institutes and sections.

This is organized scientific research, in all of the departments of human knowledge. As yet it is scarcely begun. Many of the institutes are new. Facilities are limited. The work has been held up through lack of funds, and through the destruction wrought by war and famine, but the trend is unmistakable. These people are taking science seriously. There will be a revision of programs and a great deal of readjustment and shifting of fields of work, but in the main, these propositions will evidently be followed:

(1) For each important problem that arises there must be an institute, equipped with the necessary building, library, laboratory, and other facilities.

(2) The staff of this institute must consist of experts in the field–the best that can be found in the world, without relation to their political or social opinions.

(3) Each problem must be studied as a scientific and not as a Russian problem. Therefore the research must include work, not only in the Soviet Union, but wherever the problem appears.

(4) The solution of any scientific problem, and therefore the work of each institute, consists in contributions that will enable the members of the human race to make a better adjustment to their environment.

(5) Institutes are institutions in which trained specialists do their work, and in which apprentices learn to do the work of trained specialists. Their main function, however, is research and not teaching.

Many of the ablest men and women in the Soviet Union are already at work in the institutes. Experts are coming in from other countries to make their contribution. The most promising of the students in the higher technical schools are being added to the institute staffs. By such means, science is conspicuously turned to social uses as one of the most important parts of the Soviet educational program.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf