Capitalism has many costs it does not bear. You and I do. If you have family who were coal miners, chances are you have family that died in the mines. Between 1900 and 1945 something like 100,000 workers died in mine accidents, two of my great grandfathers and an uncle included, not counting all the deaths from disease and complications from mining. Harriet Silverman breaks down the numbers and the why.

‘Reuben Williams and His Brothers’ by Harriet Silverman from Labor Age. Vol. 16 No. 8. August, 1927.

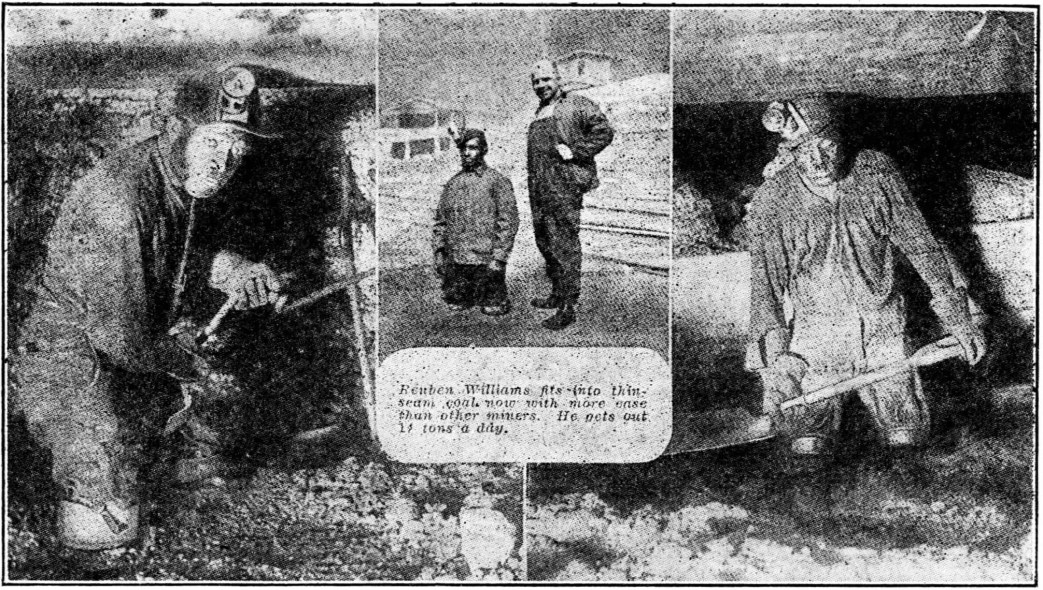

The Mine Toll

FIFTEEN years ago, Reuben Williams, a negro miner was standing in a deep railroad cut when a landslide occurred and he was pinned between two boulders. Both his legs were crushed. They had to be amputated above the knees. “Now Reuben is an expert miner in the Glen Morrison mine of the Morrison Coal Co., West Virginia,” according to a story printed in the October, 1925 issue of Coat Age. “It takes him longer to walk to his working place each morning, but he starts earlier and arrives when the rest do. Not having to stoop so much, he drills, blasts and loads his coal more easily than most men. The shortleggedness which is a handicap on the surface, stands him in good stead underground and high output of coal is as good as anybody’s…During two months recently he averaged 14 tons—drilled, blasted and loaded each working day…Thin seam coal drove him to lose his legs and now it is giving him back an honest, independent living and a lot of personal satisfaction”…Losing his legs only made him a better miner, is the conclusion of the coal corporation. By the same logic, workers who are killed in the mines ought to be infinitely better off, relieved of the hazards of coal mining, and the struggle to make ends meet. By such reasoning the coal corporations evade the issue of wiping out present hazards. By such publicity we measure their brutal indifference to the cost in human life.

The industrial waste charged against American business management by Secretary Hoover in his report of 1921 is nowhere more glaringly apparent than in the coal mines of the United States. If mismanagement and exploitation of raw material resulted merely in economic waste this would be indictment enough. But added to the waste of the natural resources of the country is the disregard of human life that is nothing short of criminal. Dangerous natural conditions combined with hazards that are controllable are snuffing out the lives of 2,500 miners annually. 30,000 serious accidents incapacitating workers for more than 14 days and between 75,000 and 100,000 accidents where the disability lasts from 1 to 14 days occur yearly. Conditions which make for this ghastly record affect approximately 850,000 workers employed in and around coal mines. Of this number 147,456 (20 per cent) are In the anthracite field and 584,985 (80 per cent) are in the bituminous.

In an effort to cover up the wholesale slaughter in American mines, statisticians and other experts figure our death rate by output in tons rather than by the number of workers killed per thousand of full time workers. Dr. Royal M. Meeker, a statistician of international reputation has declared that “to measure deaths and disabilities of workers on a tonnage basis” is utterly erroneous and bad statistic…the only just accurate basis is the man hours worked during which time the workers were exposed to the hazards of industrial accidents.” Our mines contribute 42 per cent of the world’s coal supply. The output per man per day in the bituminous mines of the United States is three times that of England and Germany, and in the past 30 years the daily output per man has increased by 67 per cent. Speed-up methods and machinery, also the fact that the coal seams of the United States are thicker, easier to get at and we utilize more and larger machinery, are the reasons for this enormous output.

Instead of giving miners increasingly better and safer working conditions, what do we find?

Major Disasters

“During the first four months of 1927, 812 men lost their lives from accidents in the coal-mining industry. Three major disasters, that is, accidents causing the loss of five or more lives, occurred during the month of May, 1927. On April 2 an explosion at Cokeburg, Pa., caused the death of six men. On April 8 a rush of mud and gravel into a mine at Carbonado, Wash., resulted in the loss of seven lives, and on April 30th 97 men lost their lives in a mine explosion at Everettville, West Va.,” according to the latest report of the U.S. Bureau of Mines Bulletin 2592.

Take the case of Utah in one explosion the lives of 172 miners were wiped out. Following this the state adopted safety measures improving its code to avoid more disasters. This brought into existence the first compulsory Rock Dusting Law. Rock dusting a mine helps to prevent coal dust explosions. Had this one preventive measure been used there is every reason to believe there would not have been this terrific loss of life in the Utah explosion. Last year at West Frankfort, Ill., more than a thousand lives were saved when an explosion occurred because the mine had been rock dusted. The cost of this one safety measure is less than a quarter of a cent a ton. Yet today there are only six states—Utah, Pennsylvania, Wyoming, West Virginia, Indiana and Ohio—with compulsory rock dusting laws.

Turning to the other important mining states and taking the situation separately for each, the U.S. Department of Labor Bulletin No. 425 issued in 1927 states:

Alabama “In 1922 as in all states where mining is important, coal mining stood at the head of the number of accidents both fatal and non-fatal.”

Idaho “Lumbering and mining were responsible for the greatest number of fatalities in Idaho for 1920 and 1924.”

Illinois “In Illinois in the years 1920 and 1923 the coal mines had the greatest number of fatalities—171 in 1920 and 155 in 1923.”

Indiana “The Indiana reporting system makes it impossible to separate the fatal from the non-fatal accidents, however in 1920 and 1921 metal products had the greatest number of accidents with coal mines second in the list.”

Kentucky “The coal mines of Kentucky furnished considerably more than half of the fatalities in 1924 and nearly half of all reported accidents were in this industry.”

Montana “The mining accident record for five years shows 558 deaths: that is an average of 112 a year or more than two-thirds of all the fatal accidents in the State coal and metal mining.”

Oklahoma Captures the prize in another direction. The constitution of Oklahoma is so framed that “fatal accidents are excluded from the compensation law.” Since 1921 no record of such cases is available. In 1920 deaths in the coal mines of Oklahoma ranked second. On January 13, 1926, there were 91 dead in one explosion in Oklahoma and not one penny of benefit collectible from the State under the Workmen’s Compensation Law to help the widows and orphaned children.

Pennsylvania Coal mines and the metal industry are responsible for the greatest number of accidents in this State. While accidents in the metal industry have decreased from 95,956 in 1916 to 47,488 in 1924, coal mine accidents show no decrease:

52,537 accidents in 1916

52,537 accidents in 1923

54,449 accidents in 1924

West Virginia “Naturally coal mining is far in excess of any industry, both in fatal (593) and non-fatal (12,152) cases.”

Wyoming “Coal mining in Wyoming as wherever it is an important industry, is a prolific source of casualties, there being 28 fatalities in 1920 and 55 in 1924.”

The states do as they please in the matter of reporting coal mine accidents. The records that are reported point to the fact that the slaughter in American coal mines is increasing. The death rate today in the United States is four times greater than in Great Britain, although the British mines are older, deeper down in the ground, more difficult to work because the seams are thin, in many cases used up and the hazards on the whole generally greater than in our mines. If in the face of these difficulties Great Britain has made conditions safer, and prevented miners from being killed off, why not the United States, where the task is easier? In the British mines for the decade ending with the year 1921 the average fatality rate, based on the number killed per thousand 300-day workers in coal mines, was 4.26 in the United States and 1.29 in Great Britain. In 1922 the rate for the United States rose to 4.89; in Great Britain it fell to 1.09. In the United States for 1923 the rate was 4.39 and for the first six months of 1924, it is estimated to have risen to 5.64.

In this, the richest nation in the world, “more men are killed by accidents in coal mines in proportion to the number of men working than in any of the leading European countries.”

Why Coal Mining Is Extra-Hazardous

Natural underground conditions make coal mining one of our most hazardous industries. About 85 per cent of the dangers to life and limb are due to:

Falls of roof and coal—resulting in 50 per cent of the accidents.

Haulage and transportation—20 per cent.

Explosions of gas or dust—12 to 15 per cent.

Explosives—4 to 5 per cent.

Electricity—4 to 5 per cent.

Accidents from falling into shafts—machinery, surface accidents, etc., approximately 10 per cent.

Explosions from natural causes such as gas pockets and coal dust, though hard to control, can be prevented by proper safety measures, such as careful and regular testing for gas, rock dusting, wetting the coal dust, proper ventilation and other methods. Falls of roof and coal which cause one-half of coal mine accidents, can certainly be brought under control. Failure to supply the necessary timber, requiring workers to put up props without paying them for this work so that they must “speed-up” in order to keep up with production, can be stopped. Systematic testing of roofs, allowing the miners enough time to do the work properly at the regular pay for mining coal, would undoubtedly help to check this source of accidents.

The “fire boss” whose time should be spent entirely—in seeking out the danger spots and inspecting safety conditions is given all kinds of odd jobs making or replacing doors, brattices, or stoppings with the result that the safety end of his job takes second place. If the mines had one full-time inspector or “fire boss” for every 20 men, the check on danger spots would soon result in a marked drop in the accident rate.

In the bituminous mines the coal beds are generally thinner and flatter. This tends to make for special dangers through the falling of coal and slate and accumulations of gas in the working places.

Explosions

Fine particles of coal dust, which are always present in a mine, are highly inflammable and explosive, the only exception being perhaps the highest grade of anthracite.

The danger of disastrous explosions of coal dust is a constant menace in bituminous mines.

Gas which is likely to be present in all coal mines, even those thought to be non-gaseous is always a source of grave danger. In fact it is decidedly unwise to regard any mine as “non-gassy”, because failure to take the necessary precautions may mean a serious disaster wherever a hidden gas pocket goes off.

In anthracite mines where the coal and rock is harder, more explosives are generally used than in bituminous mines which makes the danger due to explosives that much greater.

Falls of Roof and Coal

Although 50 per cent of miners are killed each year by falls of roof and coal, the U.S. Bureau of Mines has only just begun a study into the causes of these accidents.

Mr. J.W. Paul, Senior Mining Engineer of the Bureau of Mines, in a recent article, points out that “Falls of roof may be due to the caving in or shifting of the ground where the mining has weakened the natural support”, but also states that “No attempt is made to support the main mass of overlying material by the use of timber except in localized zones”. Also that ‘‘The laws of the states relating to timbering in mines must be reviewed and some records obtained upon the observance of the laws.

“Detailed study must be made at representative mines in the different fields to ascertain the benefits of systematic timbering versus lack of system or regulations.” He finally puts his finger on the crux of the matter as follows: “It requires no stretch of the imagination to conceive a plan or method of roof support which would give a maximum degree of safety against accidents from roof falls, but the carrying out of such a plan in some mines would be prohibitive owing to the excessive cost, the cost of the timber being in excess of the value of the mineral obtained, in which event mining would be unprofitable and the project would be abandoned.

“In some mines it may be found that systematic timbering may be less expensive than the cost of delays due to interrupted operation and the cost of cleaning away fallen material, and such a reaction would thereby reduce the hazard from falls.”

In other words, saving money, not lives, is the deciding factor.

Handling Coal

Hauling coal sometimes to distances of several thousand feet often at high speed in dark and narrow passageways inevitably results in serious accidents. If more money were spent on proper grading and care of tracks, repairing, inspection of electricity and the buying of up-to-date equipment, there is no question that such accidents could be reduced to a minimum

Blasting

About 85 per cent of the explosives used in coal mining is still black powder and dynamite.

The continued widespread use of black powder instead of “permissible explosive’ which because of the short flame reduces the danger of fire and explosion in the mines, must be charged to the corporations. Not only are miners exposed to this extraordinary danger, but they are compelled to buy their own explosives, their own safety lamps and their own tools. This practice offers an excellent chance to blame the miners for mine disasters, charging them with keeping their tools in bad condition, refusing to use safety devices or using too much powder. Compelling miners to buy their own “shot” is an economy for the corporations but it *‘s an economic hardship to the men and increases the danger of accidents by allowing the storage of explosives outside the mine, sometimes even in the miner’s home when the corporations fail to provide suitable storage places. The practice of robbing the miner’s pay envelope should be stopped.

All blasting, whether of coal or rock in coal mines, should be by “permissible explosive’, fired electrically. Black blasting powder or dynamite should be prohibited. All blasting should be prohibited during the regular working shift. This could be done if men were provided with a sufficient number of work places to enable them to mine enough coal to earn a living. The way matters are now it is often necessary for a miner to have to fire anywhere from 4 to 12 times a day to get out his coal.

Electricity

Hazards resulting from uncovered wires and the use of electricity, without special precautions to insure proper installation and upkeep, are too well known to need further description. With the increasing use of electricity in the mines the greatest precaution must be taken to avoid fires, explosions and electrocutions from this source.

Other Hazards

While the most serious causes of mine accidents are due to explosions, bad ventilation, unsafe methods of hauling, blasting, timbering, layout out of mine works, pillar pulling, poor selection and installation of equipment, other hazards also exist in and around coal mines such as falling into shafts from high steep places, accidents from unguarded machinery, being hit by objects other than coal or roof, including accidents at the surface in and around the tipple.

Mine Safety Laws Fail

Mr. Daniel Harrington, the present Chief Engineer of the Safety Division of the U. S. Bureau of Mines. in analyzing the coal problem two years ago summed up the situation as follows: “A few years ago a doctor of the U.S. Public Health Service stated that the mining industry in the United States is at least twenty years backward as to protection of the health and safety of its employes. Possibly the statement was somewhat drastic, yet it undoubtedly has much basis in fact even at this time.”

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v16n08-aug-1927-LA.pdf