I am not sure about all of the facts, but what a delight to read this wobbly history of ancient slave revolts and servile wars in the Mediterranean written to inspire current agricultural workers to rebel.

‘The “Harvest Stiff” of Ancient Days’ from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 2 No. 8. August, 1920.

A CHAPTER OF SUPPRESSED HISTORY

(The following is a portion of the first Industrial Union Handbook soon to be issued by the I.W.W., prepared under the direction of the Bureau of Industrial Research.)

Agricultural work has been looked down upon by the lily-fingered gentry of the idle classes, and agricultural workers have been despised thruout the ages as “menial” and “low”; yet the human race never could have survived without such labor and such men. Theirs are the hands that have nourished alike the brawn of the builder and the brain of the dreamer of dreams. Agricultural work is the most ancient and the most honorable of all work. It is the “man with the hoe,” and not the fabled Atlas, who has always carried the world on his shoulders.

Harvest workers in all countries and all times are surprisingly alike. They swelter today in the hot fields of golden grain just as they did two thousand years ago, and longer. The implements they use are different at present, it is true, but the sweat, the backache and the old, old spirit of revolt, are identical.

Few modern harvest workers are aware of the fact that the branded slaves who garnered the Roman crops of twenty centuries ago were organized into unions, went on strike, slept in the “jungles” and sang rebel songs, much as the “400 stiff” is doing at present. But these things are true.

The chattel slave of classical days was not migratory. In fact, he usually went about with an iron collar and a chain. But he was a rebel, and he has written a page of history that bourgeois historians have seen fit to ignore. Labor disturbances have always been unpleasant things for social parasites to consider.

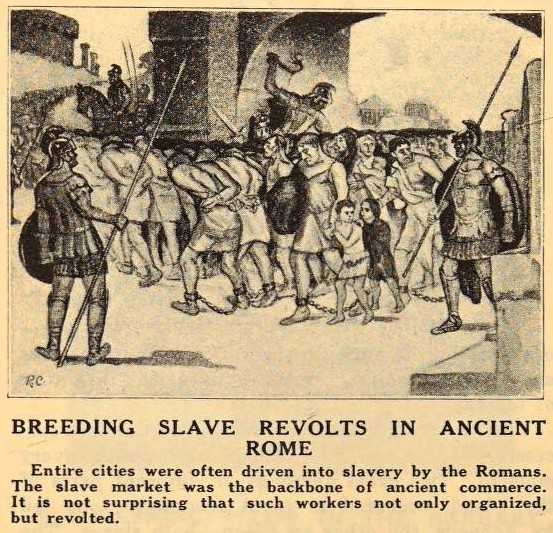

Few people know that the strikes and revolts of ancient agricultural slaves were so huge and so powerful that they shook the proud aristocracy of Rome to its foundations and, eventually, helped to shake it down. Few people realize that the harvest “stiff” of bygone days waged mighty warfare against the hated institution of slavery and, in places, actually emancipated themselves from its yoke. What is more, they forced the release of thousands of their fellow workers from prison; confiscated great estates from their parasitical “owners,” and “made the boss don overalls.” At one time 300,000 of them marched against Rome, the vicious center of the ancient slave market, and caused the mighty to tremble in their seats of power.

The “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” did not originate in Russia, but in the island of Sicily—the granary of the ancient world—one hundred and forty years before the rebel hobo known as Jesus is supposed to have been born. On one occasion, under the leadership of a runaway slave named Eunus, this dictatorship endured for a dozen years and successfully withstood the strongest armies the landed aristocrats of Rome could send against it.

Ancient Labor Unions

There were countless slave strikes and uprisings in ancient days, but only a meager few have been recorded. Our limited space makes it necessary for us to confine ourselves to the most spectacular of these. Old inscriptions’ and fragments of history have proved that agricultural and other workers were organized as long ago as one thousand years before Christ. In ancient Greece these unions were called “therasoi,” in Rome “collegium.” These unions were of three varieties: brotherhoods, burial societies and communist. All were, no doubt, the product of the old communal mode of life. At first they were used by the free workers against slave hunters, afterward by the slaves against their “owners.” The active resistance to the raids of slave merchants and the subsequent displacement of free labor on vast estates, that had been stolen from the common land, gave rise to much discontent and many uprisings. These occurred ever more frequently as the aristocrats seized the lands and sought to break up the unions. The discontent reached a climax in 58 B.C., when the Roman Senate sought to pass a law outlawing labor organization. During this time a series of gigantic labor disturbances swept great portions of Asia Minor, Italy and the whole of Sicily. It was during this period that the gladiator Spartacus made his gallant stand for human freedom. The Spartacan movement in Germany, of which the martyred Liebknecht was the head, was named after this heroic rebel.

It must be remembered that slaves in those days were branded like cattle. Like beasts, they were not supposed to have human souls or human feelings, and like beasts they were compelled to toil for their “owners.” They were in the condition that the master class of today “would like to see all modern wage workers in. But these men were closer to the period of primitive communism than we are, and the memory of freedom was fresher in their minds. The efforts of the patricians to drive them into slavery and to keep them there were always resented and always resisted.

A Revolt Against the Slave Trade

In ancient Spain, 149 B.C., a great revolt against the Roman slave trade occurred. This uprising is connected with the name of Variathus, a rebel sheep herder. The slave market had made terrible inroads upon the population of agrarian Spain, whose sturdy population was admirably adapted for agricultural labor upon the great estates of the Roman grandees.

So the spearmen of Rome were dispatched thither to carry off the strongest and best into bondage. This plan worked. flawlessly for a while.

Variathus rebelled against the cruel custom from the time he was a young man. The Romans looked upon him as an agitator, his fellow slaves as an efficient and daring leader. No doubt, like Spartacus, he was an organizer for the “collegium” of agricultural workers. Variathus kept himself out of the clutches of “the law,” bided his time, and when he struck, he struck hard.

Thousands of Spanish workers were slaving in foreign harvest fields. Many were sweating under the lash of tyranny at home. After the battle of Pydna the Romans sacked or destroyed seventy cities and took a hundred and fifty thousand free workers into captivity. Variathus continued to agitate until Spain was fairly sizzling with rebellion. A Roman general named Galba perpetrated a massacre in order to intimidate the population. It had the opposite effect. Variathus, who fortunately had escaped, marshalled the agricultural workers into an orderly foree and told them the hour had come to choose between resistance or slavery. They chose to resist. He then proceeded to drill and discipline his forces.

When the next slave-hunting expedition reached the shores of sunny Spain it was met by a determined host of sun-burned huskies armed with swords made out of sickles and spears fashioned from scythe blades. The proud invaders were ingloriously defeated. During the following twenty years Rome sent six great armies to Spain. Each one was annihilated. Slavery was a thing of the past. The fertile fields of Lusitania were tilled by free communal labor as they had been for centuries past. The black cloud of slavery had vanished.

Eventually the rebel sheep herder was murdered by Roman stool pigeons from his own ranks. But the slave market had been cheated of hundreds of thousands of victims by his twenty years of valiant struggle.

The “Dictatorship” in Sicily

The story of Eunus, the Syrian runaway slave, and the great revolt of agricultural workers in Sicily, is one of the strangest and most romantic in history. Sicily, in ancient days, was noted for its wheat. Oil and wine were produced also, but wheat was the chief product. From it much of the bread of the then known world was made. Sicily was a place of great natural fertility and beauty. Even today, travelers state, the rich, spicy odor of the island can be detected at sea, miles before its shores are sighted. But, in the days of Eunus, land monopoly and slavery had made a hell out of what should have been a paradise. Every inhabitant not of noble blood was a slave. The possessing class was becoming more greedy and vicious all the time. Also, the wealth of the island was being concentrated into constantly fewer and fewer hands. The city of Leontini, for example, had but 88 property owners, Mutice but 188, Herbita but 257. Other large cities counted its property owners by the dozens. There were absentee Roman land owners also. The main part of the population was composed of slaves—mostly discontented slaves.

All histories state that Eunus was a union man. Even in Syria he belonged to the “thiasos” of Dionysian artists, which is the ancient name for actors’ union. Eunus’ “stunt” as an entertainer was fire spitting and wonder-working by means of conjuror’s tricks. The Romans looked upon him as a dangerous agitator, but the agricultural] slaves considered him a messiah. He was an organizer for the ‘‘eranos” or union of agricultural workers in Sicily.

A harvest strike started near the city of Enna over demands for better clothing and more food. The rich land owner, Damophilus by name, warmed the hides of the strike committee with a “scorpion” and sent them back to the fields.

This action, characteristic of the greed-blind exploiters of all ages, was the signal for a strike. This strike grew into one of the greatest labor rebellions the world ever saw. The outraged slaves, after working summary vengeance upon Damophilus and his equally cruel wife, took to the mountains and “jungled up” in the vine-clad security of the craggy heights. News of the exploit spread rapidly and soon the agricultural workers of the entire island had downed tools and joined the revolt. It was then that Eunus, the agitator and worker of wonders, took command.

His first step was to urge the rebels to trample human slavery underfoot, appropriate the estates of the idle land owners and build up a free society on the old communal plan of common ownership and equal labor. One after another these estates were taken over. Their rich and idle “owners” were uniformly put to work or thrown in prison if they refused.

Class War Prisoners Released

The jails of the day were called “ergastula.” These were underground workhouses similar to the “solitary” at Leavenworth where Uncle Sam punishes workingmen for the crime of thinking. The “ergastula” of Sicily were full of recaptured runaway slaves and other workers who had committed offenses against the law-buttressed land owners. No doubt they contained their quota of union organizers, just as do the prisons of today. These gruesome holes were of course hated by the workers. One of the first things they did after the revolt was to batter down the iron doors and free the inmates. Sixty thousand slaves, mostly class war prisoners, were released in this manner to serve in the rebel forces. It is not reported that the rebels in ancient Sicily used lawyers to force the release of fellow workers unjustly imprisoned.

A great number of freedmen had become tramps, owing to the labor market being continually flooded with slaves. These joined the revolt also. The rebellion grew in strength and numbers. Small cultivators, willing to work, were spared, but the great landed parasites were summarily dealt with. During the following years most of Sicily was farmed co-operatively by the agricultural workers for themselves and their own class. Work or fight was the order of the day.

The liberation movement was unquestionably successful. It gained in numbers and power every moment. Two great uprisings, in different parts of the island, occurred in rapid succession; one led by Achaeus, the other by Cleon—both slaves. The combined forces of the emancipated agricultural workers now numbered 200,000. Sicily was conquered from the center to the sea. The flames of discontent even spread over the Mediterranean to Italy, and an extensive uprising occurred under the leadership of a man named Aristonicus.

The tyrannical Roman Senate sent army after army to crush the “servile” rebellion in Sicily. Year after year each in turn was put to utter defeat. Free territory was kept inviolate. Adding a touch of bitter irony to the work of administration and warfare, Eunus and his brother entertainers of the ancient Actors’ Union would give mock theatricals for the benefit of captured patricians. These arrogant aristocrats were taunted with a stage show contrasting the old order of things with the new. The sight of branded slaves enjoying the good things of life while their owners and overseers were toiling under the lash in the hot fields must have cut them keenly.

The dictatorship of the proletariat had now endured about ten years when the Roman landlords decided to crush the movement at all costs. An overwhelming army was massed together and, after a long and bloody fight, the agricultural workers were defeated and driven back into slavery. Twenty thousand of them were nailed to crosses on the crags of Enna. The dictatorship of the master class was again established. Eunus died in a vermin-infested dungeon in Rome. But the slaves had enjoyed ten years of freedom and they were not yet crushed, as we shall shortly see.

“Citizens of the Sun”

The revolutionary movement was temporarily put down in Sicily, but in Italy it swept onward with fresh impetus. The old Roman Licinian Law made it a crime for any landlord to own more than 500 acres of land, but Roman landlords thought no more of the law than does the American Copper trust. It had been disregarded for a long time. A liberal Roman statesman named Gracchus tried to restore the law and force the idle parasites to release their grip on the throat of the nation. He was mobbed and killed on the streets of Rome by the infuriated land owners. Then the reactionary Senate, in true J. Mitchell Palmer style, resumed the work of breaking up the labor organizations.

Pergamus, in Asia Minor, was acquired by Rome in 133 B.C. Its public lands were confiscated from the people and turned over to Roman landlords. Free labor was supplanted by slaves. A revolt was the result.

This time the rebel forces were led by a man named Aristonicus. His declared purpose was to do away with human slavery and establish a free society that would light up the darkened world like the sun. The hitherto despised and branded helots were to be called “heliopolitai” (citizens of the sun). All workers were to have equal opportunity and there was to be liberty and prosperity for everyone. All were to work together and keep the fruits of their labor for the enjoyment of the producing class alone.

It was a noble dream and valiantly fought for. But Rome was once again too powerful. Four years after the outbreak of the revolt, in the year 129 B.C., we hear of Aristonicus being strangled to death in a Roman dungeon. Aristonicus was acclaimed by the slaves of the day as a deliverer, but history has recorded little of him save his great dream and the story of his tragic death.

Sicily Strikes Again

The scene now shifts once more to sunny Sicily. For twenty-eight years after the death of Eunus, slavery flourished again in the fertile fields of “the granary of the world.” The unions had not been uprooted and the greed and cruelty of the land owners had grown apace. Slavery once more became unendurable. The militant agricultural workers retained the memory of their ten glorious years of freedom long after the ghastly price had been forgotten.

This time the uprising was precipitated by 800 runaway slaves who had found sanctuary in a woodland temple from the wrath of their masters. When the story spread abroad other slaves joined them in crowds of a hundred or two at a time. Ina short while the entire island was once more aflame with revolt. Rome immediately sent her legions to the scene, but they were harassed and defeated by the slaves fighting in guerrilla fashion. A great supply of arms and war material was amassed in this manner. A slave named Salvius had organized an army of 22,000 cavalry and foot, in the south of the island. The great estates were again taken over and the “ergastula” again opened for recruits. In the western part of the island a great strike broke out under the leadership of the man who was to be the real leader of the rebellion. A sun-burned and branded agricultural slave named Athenion had been elected leader, and thousands of slaves left their hateful labor and joined his standard at once. Athenion, though of humble origin, exhibited the rarest qualities of statesmanship and military genius from the start. He refused to accept any recruits for the fighting forces save men of tested strength and bravery. All the rest were put to work on the freed lands to insure adequate supplies for the army so that it would not be necessary to fight famine as well as the legions of Rome. Ten thousand picked men were selected in this manner. Athenion then united his forces with those of Salvius and prepared to meet the’ armed forces of the Roman exploiters. These were soon forthcoming. Legion after glittering legion of the flower of Roman aristocracy was hurled at the determined slaves in vain. After each battle the rebels were left masters of the field. Slavery had once again been abolished from the fair “granary of the world.”

“Not Defeated, but Outnumbered”

Defeat came four years after the outbreak of the rebellion. Six proud Roman Praetors had led their legions against the revolutionists, and each had crawled back to Rome defeated and disgraced. In a final desperate effort to crush the slaves, a new and huge army was assembled under a consul named Aquillius. These forces were powerful enough to put down the abolitionist rebellion and re-establish human slavery. Thousands of crosses were again ornamented with the bodies of workers who gave their lives for freedom. Athenion was also an accredited messiah, but he died like a hero, killed on the field of battle in personal combat with the labor-hating Roman consul himself. Aquillius was afterward captured by slaves in Pergamus and union metal workers poured molten gold down his throat.

But even with all this the slaves of Sicily were not yet resigned to their loathsome servitude. A young rebel named Satros escaped the massacre and subsequent man-hunt and fled to the mountains with the remnant of the proletarian army. For two years more the gallant band held the fort against all odds. In 99 B.C. they were finally captured and sent to Rome under the solemn promise of a Roman general that they would be treated as prisoners of war.

Once in Rome they were thrown in chains, taken to the amphitheater, where knives were thrust into their hands. They were told to battle wild beasts for the amusement of an audience of patricians. .Rather than give their lives “for a Roman holiday” the brave rebels shouted defiance at the thousands of their bloodthirsty enemies, and killed themselves on the spot with their own weapons.

After this uprising there were intermittent strikes and rebellions all over the ancient world. Rome, already convulsed with labor troubles, was still trying to enforce her stupid laws against labor organization. In this respect she was much like the various states in the Union that are seeking to outlaw labor organization with the notorious “criminal syndicalism” laws. In both cases the results are the very opposite of what was expected. In Rome a thousand minor disorders culminated, under the pressure of unintelligent opposition, into the famous slave revolution of Spartacus. This revolt is one of the hugest in history—worthy of comparison with the Paris Commune and the Russian revolution. At one time it actually threatened to sweep the Roman master class from power. This was seventy years before the beginning of the Christian era.

The Immortal Spartacus

The revolt of Spartacus took place in the year 78 B.C. At this time the concentration of wealth into the hands of the Roman master class had just about reached its highest pitch. A few thousand idle voluptuaries in the mighty capital owned all the then known world. Entire nations paid tribute to these bloated parasites and the working class of the world was in bondage to them. So much was idleness the fashion of the rich and toil a disgrace, that any freeman found guilty of soiling his fingers with labor was seized and sold into slavery. The inhuman slave market had been extended until it embraced every known nation. The patrician class, more greedy and licentious than ever before, was sunk in indescribable idleness and debauchery. The slave class, artisans as well as agricultural workers, was a swelter of seething discontent. The antilabor laws were being vigorously enforced. Only a spark was needed to start a conflagration. This spark, as is always the case, was supplied by the greed-blinded aristocrats themselves.

The “jus coeundi,” or law permitting free organization, had been a thorn in the side of Roman exploiters for centuries. Under its provisions labor unions were recognized by law. The slaves had, years before, taken advantage of this opportunity to organize. Throughout the centuries they had retained their organizations in the face of fiercest opposition. The patricians had succeeded in retaining their grasp upon the public or communal lands, which were stolen from the people and held in defiance of the law. Also they had supplanted free labor with slave labor on their vast estates throughout the world. Like the lumber barons of today, the Roman patricians did not intend to permit their human beasts of burden to organize and put a stop to the process of exploitation. The law permitting slaves to organize was being fought with extreme ferocity by the land owners and their tools in the prostituted Roman Senate. Then came the gladiator, Spartacus, and the rebellion that bears his name. Capitalist historians have tried to suppress the facts about this monumental revolt but it stands as one of the greatest labor struggles of history.

From all accounts Spartacus, although a physical and mental giant, was born a slave, and he was a rebel, every inch of him. There is a legend to the effect that as a boy of fifteen he stood beside his dying father, who had been nailed to a log for the crime of agitating, and swore lifelong vengeance upon the enemies of labor.

It was probably because of his powerful physique that Spartacus was sent to Capua to become a gladiator. Compared with Thracian Greece, where he had been born and had always lived, Capua appeared in anything but a favorable light. Life here was cramped and crowded. The amphitheater, with its bloody arena, the incessant battles between men and beasts or men and other men, and always the great circle of patricians for whose amusement he was forced to fight. Capua was a hateful place. Only one thing Spartacus desired more than to return to his native hills; that was to punish the cruel aristocrats for the evil they had done and were doing. In Thrace the sheep herders and harvest workers were organized. Why not try to organize the gladiators? Then someday things would be different.

Freedom, Battle and Victory

All about Capua the communal land was covered with vast private estates which had been illegally seized by the land grabbers. The old agricultural unions, which for centuries had dealt direct with the cities in supplying food, had been broken up. The right to organize had been abrogated at last. Organization was outlawed. Thousands of slaves, in the last stages of desperation, were only awaiting an opportunity to fly at the throats of their oppressors.

In ancient days when slaves exhibited fighting instincts they were seized and sent to the arena. They might there fight with other slaves or wild beasts while their masters looked on from safety, but they must never think of fighting with the masters themselves. The Roman aristocrats were as crafty as modern imperialists in this respect.

Spartacus, although a seasoned and unvanquished gladiator, loathed the killing of his fellow slaves for the perverse amusement of the drunken overlords of Rome. Also he hated the dishonored weapons with which he was compelled to fight. He was a fighter by nature and longed to battle with the sword of honor in a cause worth while. No Roman soldier would ever touch the detested weapons of the gladiatorial butcher-house. Spartacus abhorred them also. If only he could rig himself out in shining armor, with a Roman sword in his skillful hand—surely no mere soldier could stand before him!

So the dauntless Spartacus and 200 gladiators whom he had lined up for the project made a burst for freedom one fine day just as the bloody games were starting. Due to the duplicity of a stool pigeon, only 78 of them managed to escape. These broke impetuously through the guard of Roman sentries, fought their way to the gates of the city and escaped down the Appian Way. Seizing weapons on the road, the brave bond did not stop until they reached the vine-clad heights of Mt. Vesuvius. Three thousand Roman troops were immediately dispatched from Capua to hunt them down. That night the legion camped underneath the cliff where the gladiators were hiding. The situation was desperate.

Although vastly outnumbered, Spartacus and his heroic men made a surprise attack in the dead of night. The legionnaires, too confident of their numbers, were caught off guard and put to flight. A great number were killed and a large supply of arms and war material captured. The following day the gladiators adorned their mighty limbs with the polished armor of Roman centurions. The barbarous gladiatorial knives were thrown away in disgust. Multitudes of slaves flocked to the rebel forces as soon as the story spread abroad.

Another army was sent forth to capture or kill the rebels. The gladiators, eager to try out their new weapons, made short work of their pursuers.

Revolt Sweeps Onward

Each of the original seventy-eight was well trained in the use of arms. These men made splendid officers. After the little army had been well drilled it began to move forward, sweeping everything before it. The “ergastula,” or prisons, were opened along the way and all class war prisoners were invested with full military dignity. The rebel army of Spartacus soon numbered 70,000 freed slaves, desperate, determined and well-armed.

With these forces Spartacus met and defeated one of the greatest pro-consuls of Rome. Afterward he overran the rich territory of Campania, freeing his fellow workers from slavery and dungeon wherever he went. Labor organizers and agitators were dispatched to all parts of Italy. Unions sprang up like magic in all the industrial centers. Cicero, the notorious Roman labor-hater, after contemplating the successful career of the brave young rebel, exclaimed in despair to the Roman Senate: “Not only these ancient labor unions have their right of organization restored, but, by one gladiator, innumerable others and new ones, have been instituted.”

By 74 B.C. the rebel forces numbered 120,000. These were supplied with armor, weapons and supplies. The labor unions of all Italy were secretly working to keep the army equipped with war material and food. Victory after victory perched upon the red banners of the rebel slaves, for the red flag was the ancient and honored emblem of Labor long before Spartacus became a rebel. A march on Rome was started. It failed because of dissensions within the revolutionary ranks. Crixus, a lieutenant of Spartacus, envious of the success and prestige of his chief, sought to induce a portion of the army to make a premature attack on the mighty city. He managed to lead 35,000 slaves to defeat and death. Spartacus crushed the army that had vanquished Crixus. All the Roman aristocrats who were captured were forced to fight each other in the arena with dishonored gladiatorial weapons, just as Spartacus and his men had been compelled to do in days gone by. The situation was completely reversed; the erstwhile slaves were the spectators and the haughty aristocrats supplied the amusement.

Consternation reigned in Rome. Another huge army was assembled. Like its predecessors, it was demolished. The degenerate patricians, most of whom worked from one thousand to ten thousand slaves on their local estates, began to see visions of themselves going’ to work for a living, or else being thrown in jail for their crimes against labor. They were now thoroughly aroused to the seriousness of the situation.

“Better to Die a Man Than to Live a Slave”

By this time Spartacus was in command of 300,000 veterans. The often defeated Romans had now become cautious as well as determined. The slave army was harassed for a long time but not given an opportunity to fight in the open. Finally Spartacus broke through the iron ring that surrounded his army and made a break for Sicily. No doubt his intention was to re-establish the free society that had been overthrown twenty-seven years previous. But it was too late. The land owners of Rome had massed three great armies under three of its most famous generals, Pompey, Crassus and Lucullus. Spartacus and his huge army were now outnumbered. The combined forces of the Roman legions totaled nearly half a million, nearly all of them veterans of foreign wars.

A terrific and desperate battle occurred. But the gladiator and slave who had outgeneraled and defeated eight Roman armies was this time doomed to defeat. The great Spartacus, witnessing the rout of men with whom he had fought for freedom from slavery, rushed into the fray with indescribable fury and heroism. He was determined to sell his life dearly. His one aim was to meet the hated Crassus in personal combat before dying. It was a fierce struggle. Long after victory was hopeless, Spartacus was traced by heaps of slain who had fallen by his hand, and his body was lost completely in the awful carnage which closed that day of blood.

Most of the rebel heroes were butchered without mercy on the spot. Some managed to escape to the mountains. Thousands were crucified on the highroad to Rome. The sacred right to exploit had once more been made secure. History says that Spartacus, like all his predecessors, was considered a savior by the great masses that fought under his command.

“Pie in the Sky”

The wave of terror that followed the last and greatest of the slave rebellions of ancient days lasted until long after the birth of Jesus—the last of the “saviors” of the class.

All the ancient labor unions merged into primitive Christianity. This was originally a communistic and revolutionary movement. Its early adherents were lynched and persecuted just as the I.W.W.’s of today are lynched and persecuted. And, like the I.W.W., their movement thrived on persecution.

Communistic Christianity became more powerful as the years passed by. Its doctrines of equality, brotherhood and justice were all drawn from the three types of unions out of which the movement sprang. The early Christians sought to establish “the kingdom of God on earth”—not in heaven only. They expected to see the millennium with their own eyes. Jesus, the rebel carpenter, was crucified as an agitator like thousands of other rebels of his day. Like Eunus, Athenion, Spartacus and other slave leaders, he was said to have been a wonder worker and a messiah. Today he stands as an imperishable monument to the fact that unpopular movements cannot be crushed with force.

Three hundred and twenty years after the death of Jesus the Roman empire, under Constantine, adopted Christianity rather than be overthrown by it. As a state religion it became harmless as far as its menace to the established order was concerned. The “kingdom of heaven” was placed somewhere up above the clouds and the equality of man came to mean the equality of the grave. From this time onward the once revolutionary movement has simply stood for submission on earth and “pie in the sky when you die.”

Neither primitive Christianity or the horrible and bloody uprisings that preceded it overthrew the system of slavery. History had not yet sounded the hour for this hideous institution to disappear. Slavery ceased when changing conditions of society demanded another form of productive labor. When slavery became unprofitable it was abandoned. But the great labor revolts of ancient days did show the world that millions of noble workers lived in those times who would rather face death than endure the infamy of servitude. The productive system of the ancient world probably made it impossible for slaves to organize on industrial lines and achieve real solidarity on the job. Had it been in their power to do so they could have gained far more than they did with far less cost. A general strike of all harvest workers, organized into one mighty agricultural unit, might conceivably have forced. the exploiting class from their backs. But these brave rebels deserve no blame, even if they fought blindly. All honor to their memory! They proved by their gameness that they were worthy to be called men! Rotten Rome

The slave empire of Rome was dying of its own castes and its own corruption. In her last days the concentration of wealth into the hands of the idle few was only a little greater than it is in the United States today. Toward the end, torn asunder with labor troubles within and wars without, she sought to placate the rebellious slave population with free corn and amusements. “While the Egyptian fellah and the Moorish peasant were laboring in the fields, the sturdy beggars of Byzantium and Rome were amusing themselves at the circus, or basking on marble in the sun.” But this could not last for long.

When the slave market went to smash, Rome went to smash with it. The inevitable law of social chance demanded a new foundation for society. Rotten old Rome, as hide-bound as the capitalist nations of today, could not do business on other than a slave basis. Goth, Vandal and Hun swept down on her, fat, senile and defenseless. All that survived was the church that had amalgamated with her once despised labor unions. Rome had become nothing but a name.

Feudalism became the next step in human progress. The agricultural worker became a serf instead of a chattel.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports. OBU was also Mary E. Marcy’s writing platform after the suppression of International Socialist Review., she had joined the I.W.W. in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/one-big-union-monthly_1920-08_2_8/one-big-union-monthly_1920-08_2_8.pdf