Phillips with a superlative, richly photographed, look at life in Gary, Indiana.

‘The Steel Trust’s Private City at Gary’ by Phillips Russell from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 12 No. 6. December, 1911.

IN old feudal times, back in the middle ages, each baron or overlord segregated himself in a solidly constructed and massive castle, generally placed afar off from neighbors on an eminence which afforded a view of the surrounding country so that an approaching enemy could be instantly detected.

This castle was heavily guarded. Armed watchmen and lookouts were constantly on duty. Any stranger requesting admittance had first to give an account of himself before being allowed entrance to the sacred precincts. Surrounding the castle was a high wall. Running around the foot of this wall was a deep moat or ditch. Any assailants had first to cross this moat and then surmount the walls before they were even in a position to attack.

Grouped as closely as possible around the castle were the little homes and farms of the villeins and serfs, or tenant farmers. They were supposed to be under the protection of the baron. They depended on him for rescue and defense in case of sudden foray and pillage by enemies.

It is true their homes had usually been fired and their crops destroyed before the baron could be waked out of his comfortable sleep, but anyhow there was some comfort in the notion that he was their good guardian and protector. For this “protection” the tenants owed their lord allegiance and must be ready to lay down the shovel and the hoe, or whatever tools they used in those days, and be ready to go out and get themselves shot whenever the boss felt like starting something.

In addition, they had to pay a substantial yearly tribute to the baron in the shape of garden and vineyard products for his table, meat for his larder, and provender for his horses, not to mention young and tender daughters for the satisfaction of his lusts.

Oh, it was a bully arrangement! You see these tenant boneheads had the idea that they couldn’t get along without the baron, despite the fact that they did all the fighting and dying anyhow and that they could raise crops and keep them for themselves without letting Lord Goshamighty in on them. Of course, the baron was satisfied with his end, since he got all the good things of life without working for them, so who was there to raise a kick?

We moderns love to think that we have progressed mightily since those days and that we haven’t any such fool arrangement now.

Haven’t we, though? The answer is, yes. We’ve got such an arrangement right here in the 20th century and no further away from Chicago, that center of light and learning, than 25 miles down into the sand dunes of Indiana. This modern-medieval institution is known as Gary and it seems so much like a new thing under the sura that everybody calls it “the model city.”

And it is, too—for the Steel Trust which owns it. The trust has things there just like it wants them and hence doesn’t object at all to having it called a “model city.” So pleased is the Steel Trust with it, in fact, that it is going to build more towns like it afar off from meddlesome agitators and troublesome wage scales.

Gary is the modern prototype of that baronial castle of ye olden time. Come on down there with me and I’ll show the doubter how Judge Gary, of the Steel Corporation, has patterned his town almost on the very lines laid down by Lord Goshamighty.

The Steel Trust has placed its giant mills there on the edge of Lake Michigan, where its belching smokestacks can look afar off across the water on the one hand and the level prairie on the other.

The big plant is guarded on both inside and out. Armed policemen and watchmen stand at the gate and all visitors must undergo inspection and exhibit the proper credentials before passing through. Surrounding the big group of mills is a high board fence. Cutting off the plant from the mainland is a wide and deep moat of black and sullen water, crossed by means of a concrete bridge made of the cement turned out by another plant of the Steel Trust’s further up the Michigan Southern Railroad.

Spread out like a fan from the gate of the plant is the town of Gary, its huts and homes nestling as closely as possible under the blackened funnels that night and day pour out their smoke and flame.

In these little box-like cottages and shacks dwell the steel barons’ ten thousand wage slaves. They live in Steel Trust houses, they walk on Street Trust land, they buy from Steel Trust stores, they deny themselves comforts and luxuries that they may put a little portion of their earnings in Steel Trust banks, and not once a year, but once every 12 hours they obediently leave their bunks to march down to the Steel Trust mills and pay tribute to their masters from the one thing they own—their labor power.

Oh, it’s a bully arrangement! They give the Steel Trust all they have and in return the Steel Trust lets them live. The wage-slaves seem grateful for the privilege of being allowed to work. The Steel Trust is pleased with their peaceableness and quietude. So maybe it’s a satisfactory arrangement all around.

“Maybe,” you’ll notice we say; for the slaves of the steel works don’t talk much. They’ll discuss baseball with you, or last night’s show, or the dance next week, or the scrap in Mike the Mutt’s saloon a week ago; but about their life and labor they preserve a silence that may be ominous or not, as you look at it.

It is perhaps enough to say that wages in Gary are from 15 to 25 per cent lower and the cost of living from 25 to 35 per cent higher than they are in Chicago, less than an hour’s ride away. Twenty cents an hour is good wages for a skilled laborer. Working hours for the common laborer are 12 a day, seven days a week. He toils in shifts—two weeks by day and two weeks by night.

The skilled mechanic is somewhat better off. He works ten hours and is paid about 30 per cent less than the union scale calls for in Chicago.

The Gary mills have gathered- their workers from the ends of the earth. Most of the establishments that deal in necessities, like clothing, furniture and drug stores, are compelled to print their signs in seven languages. Most of these toilers are, as can be guessed, foreigners. The nervous American cannot stand up long under the frightful heat and long hours.

The majority of Gary’s workers are single men and most of them are young—say between 20 and 40 years. One seldom sees an old woman in Gary, unless it is a wrinkled old crone who is brought to look after the children of several families, and an old man is an exceedingly rare object. That the majority of Gary’s married couples are also young is shown by the fact that most of the tots who enter the Gary schools tell their teacher their parents have no other children, or if there is another child it is generally a young baby. This indicates that most of Gary’s married workers were united about five or six years ago.

Gary then, as these facts show, recruits its toilers from the young and the restless. A large portion of the population, which is now about 25,000 in all, is floating and fluctuating. No sooner is one regiment of workers used up by death, injury, disease or physical weariness than there is another regiment instantly ready to take its place. There is a group of youngish and stoutly built men standing about the Gary employment office almost all the time begging for jobs. Young workingmen of all trades are flocking into the town every day, most of them on the bumpers of freight trains. They have become restless, they long for a change of scene or occupation, and because Gary has been so well advertised by capitalist newspapers and magazines they flock there under the impression that jobs are easy to get.

I was walking near the steel plant gate one morning when I was stopped by a husky young fellow in stained and dusty clothes.

“Mister,” he said, “which direction is Pine from here?”

I pointed in the direction of the town named.

“I want to jump the next freight for her,” he remarked.

“Looking for work?” I asked. He nodded. “Have you tried here?”

“Yep,” he said. “Nothing doing, they told me. But right after that they hired three men, and there was I standing looking on and as hungry as hell. I guess I’m too ragged. I been on the road so long I guess they thought I looked too much like a bum.”

“Where did you come from?”

“Hazleton, Pa.”

“What did you do there?”

“Miner.”

“You had a steady job and you left it to come here?”

“That’s right. Maybe I was a fool, but I don’t give a damn. I got tired of the mines and I wanted to see the country. I thought it would be a cinch to get a job here—they told me there was plenty of ’em. But not for me, it looks like. Well, me for Pine. I’ve loafed long enough. I got to feed my belly now.”

And with a wave of his hand he was off towards the railroad station.

This young worker was perhaps typical of the class that makes up the majority of Gary’s population. He and others like him are lured here by the carefully spread tales that there is plenty of work for all.

Probably one out of five of these young fellows gets a job in Gary. He works at it a while with the intention of going somewhere else as soon as he tires of it. But he perhaps meets a girl he likes and marries her. A baby comes right away and he now finds he must stick to his job if he would feed three mouths regularly.

His earnings, we will say, are $50 a month. Out of this, $25 must go for rent. He cannot obtain accommodations at all decent for much less than this in Gary. He makes his home probably in a two-room “flat” situated in the third story over a saloon because he wants to be near his work and save time and carfare. Groceries are 20 per cent higher than elsewhere and he finds it hard to feed three for less than $14 a month. That’s $39 gone. Clothing costs his family hardly less than $5 a month more. That’s $44. Fuel, light, etc., cost $4 a month more. That’s $48, leaving $2 a month for amusements, drinks, drugs, doctors’ bills—say, where does a steel worker get off at, anyhow?

But still he clings to his job. He knows that the minute he lets go a half dozen men will come on the run from the gate outside to take his place. Thus is competition among the workers incessant and thus are wages kept down and the toilers tamed.

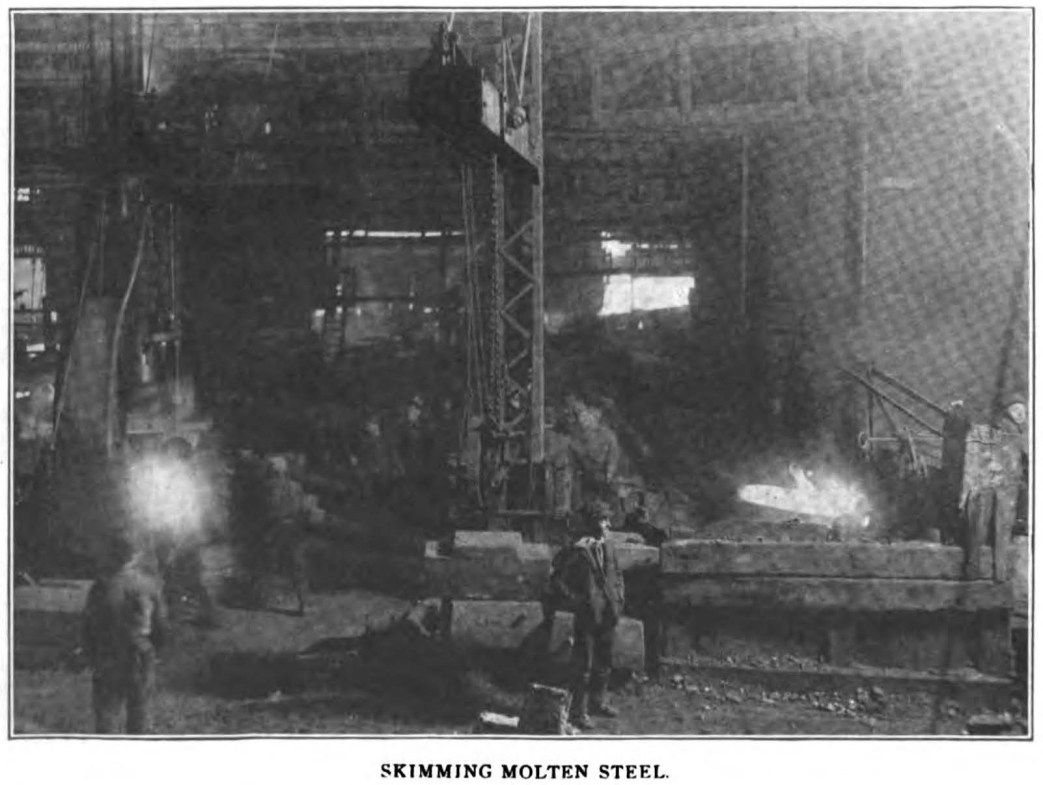

But that isn’t all. At any moment during the day or night while the workers in the plant are grappling with the white-hot rails or plates and hurrying them hither and thither, a huge swinging bucket, livid with molten steel, may be tipped over; a derrick may bump and drop its hissing load; a pair of tongs may slip, and it will be all over. Another bread-winner will be snatched up, hustled upon a stretcher and his body hurried to the Trust’s hospital or to its private morgue. What, then, about the girl wife and the baby? There is little for women and children to do in Gary. Rough, careless, brutal, burly, indifferent, it is a town for men only.

Figures are not obtainable as to the deaths and injuries in the steel works at Gary. All inquiries are met with a shake of the head or a shrug of the shoulders. Workers who know that Death sits at their heels constantly during their hours of labor do not care to talk about him much. They will admit they know he is there, but they will then change the subject instantly.

“Funny,” said a Gary steel worker as I passed him a bowl of steaming hot potatoes across the boarding house table. “One day I saw a man reach out with his tongs to grab a red-hot rail. I don’t know what caused it or how it happened, but the next minute I saw the rail coiling around him in a spiral like a big snake. He gave just one yell and then there was spurts of smoke as it closed around him. It didn’t leave much of him, either.”

Some say that an average of 25 men are killed in the Gary steel works every month and three times that many are more or less seriously burned or otherwise injured. These figures may be exaggerated; I do not know. The Steel Trust maintains its own hospital inside the plant and as soon as a man is hurt he is hurried there and the outside world never hears of the case. If a man is killed, the coroner records the death under “accidental deaths” and lets it go at that. Formerly the Steel Trust did not report the deaths in its works even to the police. Nowadays the usual official reports are made, but, of course, they mean nothing and never go any further. No squeamish or timid man is wanted by the Steel Trust. Outside its gate at Gary it has posted this ominous sign:

“Unless you are willing to avoid injury to yourself and fellow workmen do not ask for employment.”

But when one leaves the steel works gate Gary is not a bad town to look upon, as most industrial towns go. Its principal street leads directly to the entrance of the plant and is named after the favorite thoroughfare of its founders, “Broadway.” Like the original, it is brilliantly lighted by night and is richly lined with boozoriums and ginmills.

There are only a few of these in the main business section, but toward the south end, in the working class district, the street is lined with solid blocks of them. At first glance one would think there is a straight mile of them, not interspersed with other stores, but continuous with saloons.

Yes, the Gary workingman drinks and he drinks heavily. The liquor problem is one we are going to know more about when it has been studied scientifically under Socialism. At present the average Gary workingman is trying to solve the problem by drinking it down and out of sight. We may watch him gulp his poison with sorrow, but we can’t blame him.

If we were all in his place we would doubtless do it, too. Confined all day or all night in a man-made hell, his body exposed for hours to intense and blistering heat, his lungs covered with a coating of fine steel dust with which the air is laden, what wonder that there is set up within him a desperate craving for drink? If there were no other factors, the long monotonous hours he toils would naturally drive him to the warmth and light and seeming good-fellowship with which the saloon abounds.

But as elsewhere, not far from these garish saloons is their inevitable accompaniment—desperate, miserable poverty. The fester known as the slum is already noticeable in Gary, though the town is but five years old.

The slum has begun in Gary with the “shack.” This is a long low hut made of boards driven into the sandy ground and covered with tin and tar paper. The structure is not as high as a man and one must stoop to enter the doorway.

Gary already has hundreds of these shacks. They are inhabited mostly by the unskilled foreign workers, who crowd themselves in at the rate of 15 or more persons to a shack. Such dwellings, or rather pig-sties, are cheap, and the foreign worker is forced to put up with them if he would save any money to send back home. The Steel Trust has built about 700 “model” dwellings in Gary, but these are not for the laborer. They are for foremen and other highly paid employes.

Such is Gary. And now what’s the answer to this industrial hell, this “model” town of brilliant lights–and blackened smokestacks, this don’t-give-a-damn indifference to life and health, this brutal, overwork and cruel under pay?

Curiously enough I found the answer written on the archway of the railroad bridge that crosses the short plaza leading to the steel works gate. On the white concrete wall some wanderer had scrawled in letters two feet high the one word—Socialism.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v12n06-dec-1911-ISR-gog-Corn.pdf