Sen Katayama wrote for the ISR fot most of its existence. Here, on the strike wave and growth of the workers movement in the early 1910s. With some great photos.

‘The Old and the New in Japan’ by Sen Katayama from International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 9. March, 1913.

FIFTY odd years Japan has awakened from its semi-barbaric slumbering satisfaction with the old feudal system. It has passed through two big wars in ten years, while draining national resources by military expansion, heavy taxation and directly through labor exploitation prevalent all over the country. There have been growing up formidable capitalist classes that are squeezing the workers’ blood by unbounded exploitation and the high handed protective system of industry and commerce. The protective tariff, that was legalized a year ago last July, gave the capitalists free hands in charging monopolistic prices on manufactured goods up to that time supplied by the foreign market cheap. Consequently the working class is suffering more acutely than ever before on account of low wages.

The cost of living has been increasing steadily for the last two decades but wages have not, so the losers always have been the wage earners.

We do not lack an Astor in Tokyo. Such being the case, some rich capitalist owns a pet dog that costs him 10,000 yen ($5,000), and Mitsubishi owns some thirty hunting dogs each dog costing to feed 80 to 100 yen a month. This means wages of 150 to 200 days of a day laborer just at present.

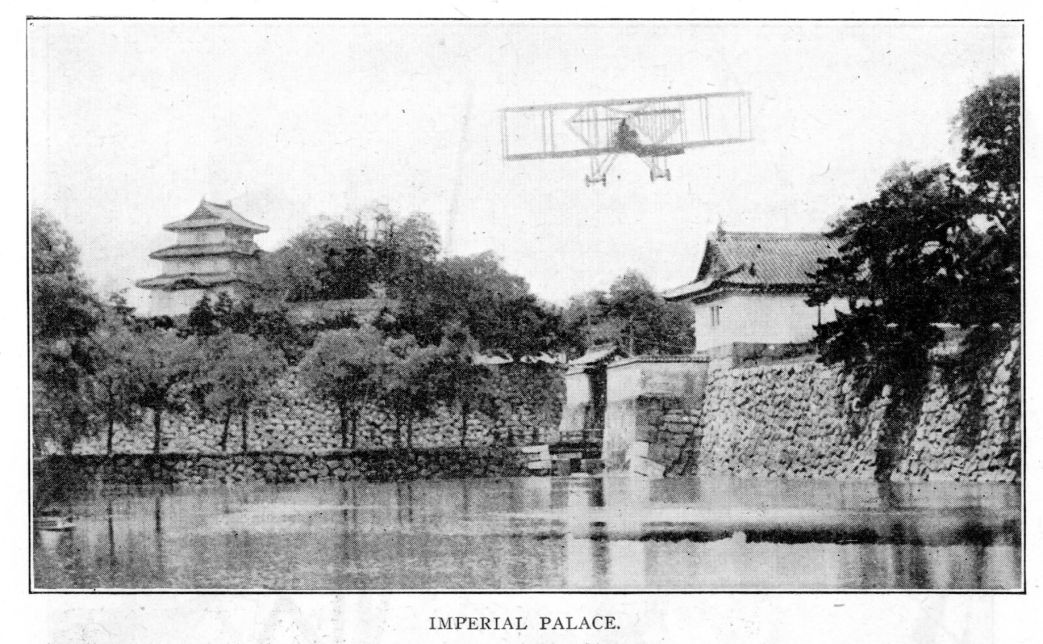

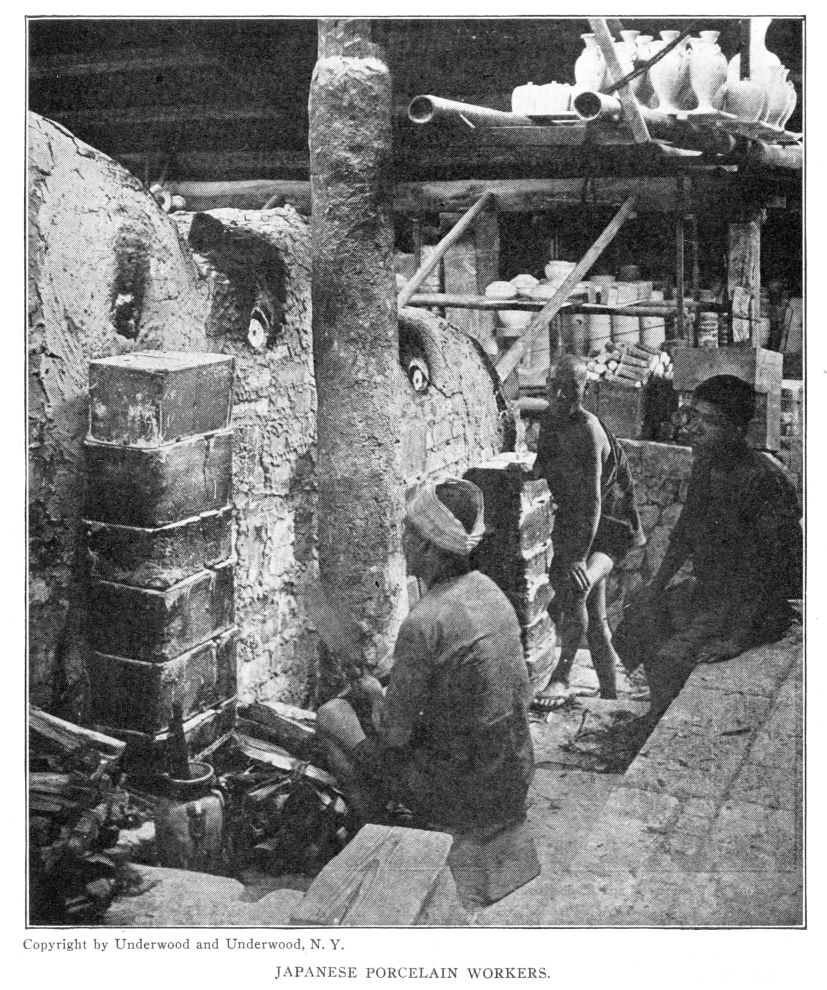

While many workers unable to pay car fare walk along the rough or muddy roads, by their side there goes an American or French made automobile that costs 5,000 to 7,000 or 10,000 yen. The rich are paying 100 yen an ounce for Hoobigan’s perfume, but many poor children of workers go to school without breakfast. We watch areoplanes or balloons flying over the sky across the city of Tokyo, while the poor can not ride in trains, but must walk on rough country roads with coarse straw sandals, and carry burdens on their backs or shoulders. Most modern machines are imported or home made for use in industry and commerce and often next door to them the most primitive tools are used to conduct the business or industry. A few pictures will convey the idea of things in Japan to your readers.

Although old Japan is passing away pretty rapidly, yet you can see many feudal relics surviving everywhere in Japan. Side by side of the most advanced ideas of the western world are old Japanese customs long unused and forgotten elsewhere.

Harikari or suicide was taken up by Count Nogi, the so-called hero of Port Arthur at the time of the late Russo-Japan war. Nogi sacrificed over twenty-five thousand soldiers in order to take Port Arthur; now this stern old soldier killed himself at the death of the late emperor, and this act has been praised by the people as divine Many thousands of persons are making the pilgrimages to the self-destroyer’s grave.

It is impossible to read the signs of the present moment, but this much is certain, scientific knowledge has been steadily applied to every sphere of life more and more and in consequence the old order of society will be bound to pass away whether conservatives like it or not.

Just now we have no freedom of speech or association; everybody is talking or writing differently from what really they think or know. Most people become hypocrites or philistines for the time being. But this state of things will not continue indefinitely. It will change sooner or later; and I have a bright hope in the near future. Intelligent men fear the present status and are attempting to remedy conditions by halfway measures or charitable undertakings, but the social reforms of bourgeois men will never succeed in helping the working class. Capitalism itself will drive the workers to Socialism. There is nothing else that can help them.

THE LABOR MOVEMENT IN 1912.

The year just passed has been an eventful one in the Japanese labor movement. It began with the great strike of the street railway workers in Tokio that threw the whole city into confusion upon the greatest national holiday, when everybody wanted to ride in the cars. I have already reported this strike for the Review, which was a great victory for the men, coming as it did just when their labor-power was most needed.

On January 14 the sailors on carrier boats from Yokohama to Tokio struck for higher wages. Owing to police interference and brutality, their efforts resulted in utter failure.

March 28 saw the strike of the Yugen dyers, whose wages with their employers is based upon the price of rice. They demanded a wage increase to equal the rise in the price of this staple article of food. The heavy hand of Authority again crushed out the rebellion and the workers returned with a promise of a future rise.

During March came also the strike of 30,000 navy yard employes. The last Diet voted them a sick and accident benefit, so they desired to distribute among those who had paid in to their own mutual aid society the funds in their treasury. They demanded also a wage increase.

Policemen and gendarmes were sent to arrest all strikers. They succeeded in arresting some thousand men, it is claimed, and repressive measures were so severe that the men knew they were beaten.

The sailors’ strike was more successful. They possessed some measure of organization and demanded increased wages. On April 22 over 80 per cent of the sailors and firemen struck at Yokohama and the companies acceded to most of their demand Strikes are a new thing in Japan and the past year has seen many of them. But the rule has been defeat through lack of education and organization and through police interference.

Up till very recently the Japanese have been an obedient people. They have toiled long, without questioning their hard lot. But times are changing very rapidly. Large bodies of workers are being drawn together by new methods of industry. They are coming to feel a common bond. Class consciousness is being born of the very conditions of Capitalism itself.

In quoting from the February number of the Century Magazine, we find new information on industrial and political Japan:

“The (Tokio) strikers received an increase and went back to work. Several of the leaders were severely punished on the ground that they put the public of Tokio to serious inconvenience, hence had committed a crime against society. The men punished were regarded as martyrs by their fellow workers…and since then there has been a marked and unusual hesitancy on the part of those in authority in dealing with such cases in a summary or harsh manner.

“As yet the Japanese laboring men have not acquired sufficient boldness to strike for an avowed purpose, but by concerted action they fail to report for duty. When asked why they do not appear they plead physical ailments and thus escape legal action. They accomplish the desired end, however, and the result is the same.

“At first and up to a recent date, the government dealt with strikers and labor agitators as criminals, and punished them as such. But as the disturbances increase, it has become apparent that this method is not practical.

“The price of rice per bushel has increased from 72 cents in 1892 to $2.12 in 1911. Western ideas and the increasing cost of living are bringing about a state of restlessness and dissatisfaction potent with serious possibilities.”

From Comrade Rea Now Touring Japan

To those of us who are accustomed to liberty for carrying on a regular system of socialist propaganda and union agitation, the attitude of the Japanese authorities toward these movements comes as a distinct surprise. This is especially true because only a few years ago the emperor is supposed to have granted his subjects a constitution granting them at least a few personal liberties.

Within the past month I have visited many comrades in Tokio. From what I could gather, the heart of the little propaganda movement lies in this, the capital city, where a few faithful Socialists gather occasionally to exchange views and plan for further carrying on the great work.

As they are not allowed to meet as a political body, these functions are always more or less of a social character. Tea and cakes are served, cigarettes are lighted and a pleasant time is enjoyed by all. Speeches are made by different comrades and all things possible are done to continue the work.

Upon the evening I attended one of these gatherings, a Japanese comrade, carrying a child strapped to his back (the national way for carrying the children), told us how he had just been discharged from his job because it had become known that he was a Socialist. The employer of this man informed him that he never employed Socialists. He was an experienced shoemaker and earned 42 yen, or 21 cents, a day.

As soon as a man is known to belong to the movement he begins to receive, what he naturally believes to be, more than his share of attention from the police.

During my visit the police were doubly vigilant. When I left home in the morning with a comrade, to visit various places of interest in Tokio, we found them waiting for us outside the door. They stayed with us all day; took the car when we did and were more than attentive. Comrade Sakai, with whom I was visiting, introduced me to some of them. I feel sure many were disgusted with their jobs, but they have to obey those higher up.

Nearly every Socialist I met had served time in prison. Comrade Sakai has served several terms—two years on one occasion. Comrade Katayama has not long been free, having been sentenced to a term for advocating the cause of the striking street car employes in Tokio. Another comrade recently died in prison while serving a two-year sentence for writing a pamphlet exposing the horrible conditions of the Japanese peasantry.

Out of a population of 50,000,000 in Japan, only 1,500,000 possess the ballot. There are as yet no such things as either industrial or political freedom in Japan.

But every year brings home students who are teaching the message of Socialism, and every day brings greater hardships to the workers in Japan. And with the great organizing power of modern industry and the misery of the people the seeds of revolution are bound to grow with ever-increasing speed.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n09-mar-1913-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf