Ed Falkowski, himself a miner from Shenandoah, Pennsylvania continues his fantastic series on Weimar Germany with a visit to the familiar, and dissimilar, Ruhr village of Bottrop.

‘A German Mining Town’ by Ed Falkowski from New Masses. Vol. 5 No. 6. November, 1929.

I. BOTTROP—RUHR’S HUNKEYTOWN.

Few people ever wanted to come to Bottrop. It’s 80,000 inhabitants represent an accumulation rather than a settlement. Bottrop is a place people “fall into.” A part of the Ruhr coal-pot.

Bottrop, like its sister towns—Gelsenkirchen, Buer, Hamborn—is a “hunkeytown”. Over 80% of its inhabitants are Polish immigrants; 10% represent the Hungarian and Slovakian elements; and only the remainder are descendants of original Germans.

Within fifty years the onetime village blossomed into a huge, unhappy city. This was during the Ruhr’s bigboom period. Thousands of foreigners were induced to part with their landpatches and seek their fortunes in the Ruhr. Peasants dreamed of this region as they dream of America—a place one can pick up sudden wealth.

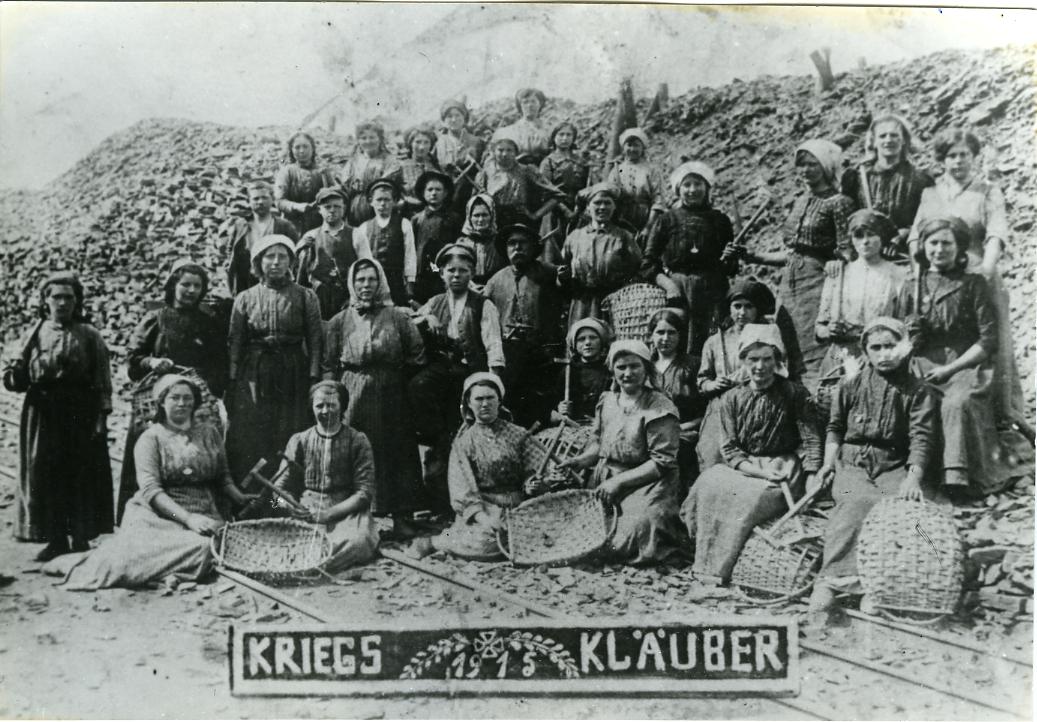

Their disillusionments have printed themselves on their faces. Lean, hollow-cheeked, hot-eyed, the men revolve in eternal circles of shifts, struggling to keep bread on the table. Dirty, underfed kids play on the local ash-banks, lambasting one another with rusty tin cans, or rooting for pieces of unburnt coal.

Mothers, whose wombs turn out offspring with an ominous regularity, fight the daily battle against dirt and hunger’s monotony. These Polish and Hungarian women dream of their homelands with deep regrets. “Everything is so sad here,” they tell you. “And there, everybody, although poor, seemed happy and content.”

But nobody ever leaves Bottrop again, once he has got deeply enough into it.

II. STORY OF AN INCUBATOR.

Bottrop enjoys the dread distinction of being the Ruhr’s first child-incubator. It is, to paraphrase the German expression, “childrich with poor children.”

Everywhere one sees children. Lean, undernourished creatures, turned loose upon the streets and grassplots to spend hours in play. Kids with withered arms and humped backs, and some with faces of idiots. One is amazed by the large swarm of unhappy children who “bless” the table of the miner whose income can no longer include meat on his bill of fare.

Church and officialdom encourage this enormous fertility. On one occasion a group of radical women tried to engage the Schauburg—a local kino—for a public lecture on “sex reform.” The mayor refused permission to hold the lecture on the grounds that “Bottrop’s honor must stay fast.”

Priests advise women that remaining longer than three years without a child becomes a sin.

The government itself encourages the childbirth increase, the parents of a twelfth child receiving a handsome cup and saucer, of genuine Meissen-porcelain, and decorated with the black-red-gold of the republic, from the public welfare minister. The seventeenth child usually enjoys the distinction of having Hindenburg for its godfather.

The happy father’s wages are increased 16 pfennig per day—“child-money.” Not enough to buy a smokable cigar in modern Germany.

The “Work-paper” congratulates the “lucky parents” of a newborn child, and the social-insurance office covers all birth expenses. But the problem of income now assumes magnified dimensions for the poor father. So far as he is concerned, the birth could be listed among the “accidents” in the mining industry. It is merely the outcome of a sexual technique which still awaits its share of “rationalization.”

III. STREETS HAVE MEMORIES.

1920—the Kapp Putch year—singled out two Ruhr cities for bloody distinctions. Hamborn was one of these, Bottrop, the other. The Communists made their stand against the government troops in Wesel, retreating finally until they reached Bottrop where another battle was fought.

The townhall still bears bullet holes from those dramatic days. The big battle however was fought in the “Polish gangway”–a swampy miner-settlement on the northern fringe of the city. The communists fortified themselves behind the walls of Prosper 3, a Rheinischen Stahlwerk mine, while the government troops occupied the slaughterhouse about a kilometer away.

After the communists retreated still further, Bottrop was filled with policemen and a terrific vengeance followed. Hundreds of workers were stood up against the wall and executed. To be suspected of red sympathies was enough to place one in front of the firing line. Miners on their way home from work were dragged in front of the murderous squad and butchered.

The fact that Bottrop is a “hunkeytown,” that the murdered victims were mere polacks and foreigners, inspired the “legal” butchers in their bloody occupation, made them more brutal than usual.

Everybody knows what followed. The republic was “saved,” to the present dissatisfaction of the two extreme social groups—the workers and the capitalists. Germany has become an economic and political rocking-chair, rather wobbly in its entire internal structure. Its freedom celebrations (Constitution-Day) consist usually of police manoeuvres—an ironic comment on the tone of peace and freedom in the Germany of today!

IV. THE DISMAL SWAMP.

The town’s center boasts of its Woolworth, its movie theatre, and its large, modern store. Bottrop has over 200 saloons, and not a library or a decent bookshop.

The business core is surrounded by long streets of monotonous brick houses, smoky and tired, one house looking exactly like another, with strips of black, dusty road between. These are the mine-dwellings, belonging to the coal company. 80% of the land belongs to the Rheinischen Stahlwerk corporation.

These swamps of depressing houses accommodate the miner and his family. A fifth of his income each month pays the rent for the three or four rooms which he enjoys. Frequently this narrows down to one or two, because of the pressure of population growth.

Crudest sanitary conveniences, flies, smoke from the mine, lack of breezes in summer and ungodly cold in winter, give atmosphere to the family’s domestic history.

The pressing poverty inspires much thievery, so that every one lives under eternal lock and key. Cases have been known where pigs were chloroformed and slaughtered in their stalls by thieves, and the flesh hauled away during the night. No one trusts another in these miserable jungles of repeated houses.

Poverty is everyman’s common friend here. Its harsh touches are everywhere evident. Patched clothes, dried breadcrusts, the empty despairs stamped on pale faces, the murders and the suicides reflect its gruesome influences.

Meanwhile the coal production soars to maximum figures. The shakers shake faster; the bore hammers bore deeper; the shafts operate more intensely than before. Engineers have harnessed the miner within their new rationalization schemes.

He works twice as hard as formerly, for about half the wages he previously received, as measured by purchasepower.

Every pay day the miner shakes his head. Payday is always for him a bitter day of reckoning, in his effort to foot living costs. But some day the table will be turned, and payday will be a day of reckoning for his lords. In that day the miner will be the paymaster.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1929/v05n06-nov-1929-New-Masses.pdf