An interesting article on a number of levels, beginning with the fact that W.E.B. Du Bois’ Crisis published it. Dissident Communist, and veteran leader of the Passaic strike, Albert Weisbord with a sharply antagonistic ‘left’ critique of the Communist Party’s positions and practice in organizing Black workers. The ‘Negro Chamber of Labor’ was a Communist League of Struggle project in New Jersey spearheaded by Frank Griffin, a Black former member of the Communist Party expelled with Weisbord in 1930.

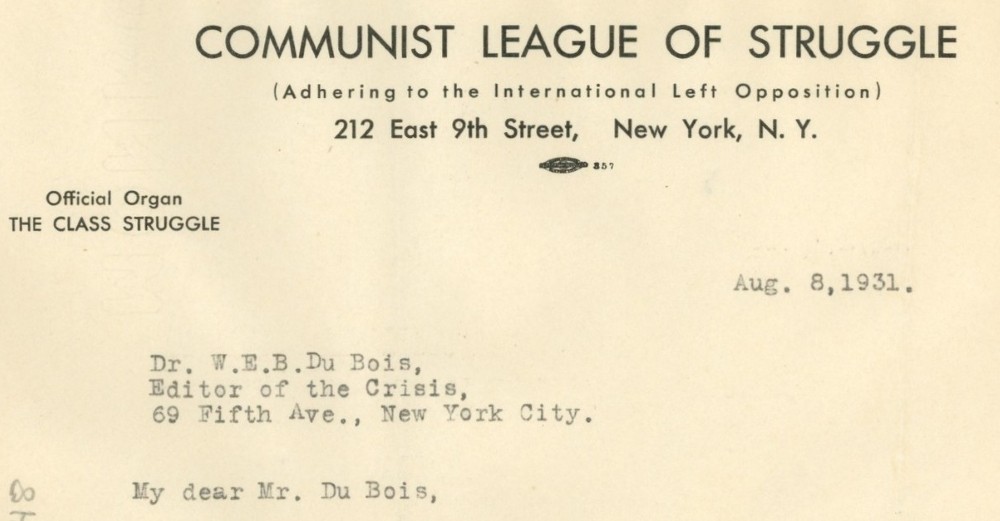

‘A Negro Chamber of Labor’ by Albert Weisbord from The Crisis. Vol. 41 No. 7. July, 1934.

Mr. Weisbord will be remembered as the sagacious leader of the Passaic strike of 1926. His analysis of the problem of lynching is novel in that he finds a place for it in the class struggle. His condemnation of the radical Negro “prima donnas” ought to be read with interest.

AN interesting experiment is being made in Paterson, New Jersey.

In that city there is being organized a Negro Chamber of Labor. Paterson is like the typical industrial city of this country. The several thousand Negroes in the city are totally unorganized. Outside of the poolrooms and churches, there are virtually no places where the Negro workers can turn.

Of course, in Paterson, there are racially mixed organizations which stand for equality and which take in Negroes into their organizations. However, the fact remains, that only a tiny, almost infinitesimal, proportion of the Negro people are in such inter-racial organizations. Such organizations can train the vanguard of the Negro masses, but the average colored worker is not, and, under present circumstances, cannot be drawn into them. Supplemental to the black/white organizations already existing and supporting them, there must be established Negro organizations where the most backward Negro worker can feel at home and realize that here, at last, is a place where he can bring all his troubles and find sympathetic support.

As a matter of fact, in many instances, this type of radical organization, far from developing a vanguard among the Negroes, has really set back the organization of the colored workers. How many intelligent Negroes has the Communist Party spoiled, for example? The advanced Negro worker, once brought into the Party is soon separated from the rest of the Negro people whom he once knew. He becomes isolated and estranged from his own race, where in most cases he can do the most effective work.

Concurrently, these inter-racial organizations are so immature themselves, are so fond of “shows” and “pageants” and “demonstrations,” that they have used the few Negroes who have entered their ranks as exhibits and show pieces. Like Voodoo witch doctors who put on masks to impress their tribe members and enemies, the Communist leaders dance around and around with the few Negroes in their organization as their own “black masks.”

Most of the Negroes brought into such inter-racial organizations soon realize their role. The majority leave in disgust. A minority become reconciled to their servile status, they enter into the clique leadership and become part of the apparatus. They take on the cynicism of the white bureaucracy. Or they strut around like prima donnas. Do any of them really undertake serious work among the Negro masses? How many of them?

And yet, sooner or later, mass organization of the Negro exploited and oppressed toilers must be attempted. In the same proportion as Labor realizes itself and its own importance, must the Negro come into his own and take his proper place in the very forefront of Labor. In the United States, especially, the Negro represents the very heart of the Labor question. Precisely because the United States was the “freest” country in the world, for this very reason was it forced to become the country of the most developed slavery. This was so, because here, instead of the peasant turning into a proletarian, as in Europe, there was the opportunity for the worker to turn into a small property holder and to work for himself. If, in America, all classes, relative to Europe, were moved up a notch—up and back, if you please —if in this country the worker turned into an entrepreneur or farmer or mechanic, who was there to create the profit for the capitalist? The answer was obviously the Negro, the slave. Labor had to be chained physically before it could be exploited in the factories and fields of capitalism as profit-making labor.

In the literal sense of the term the Negro has symbolized simple, unskilled, labor, the bases of all labor in this country. And now when all labor has become unskilled, when unskilled labor is the backbone and the mainstay of all the struggles of the oppressed, can the Negro fail to take his place there, in the very vanguard of the struggle? Let us say plainly that, here in America, THE NEGRO IS LABOR AND LABOR IS THE NEGRO. That is why the Negro question is in reality the very heart of the Labor question. And he who does not understand the Negro question can not begin to understand labor in the United States.

In many respects the Negro worker is far in advance of his white brother. Is there any Negro who believes that there is “democracy” in the United States, that all men are treated as equal, that there are no “classes,” that everyone has an equal chance to become President, etc.? All the silly illusions which still exist among such large sections of the white workers have absolutely no place among the Negroes. In this land of “equal opportunity,” every Negro knows that somewhere there is a social “line” which one can cross only if he means to fight to a finish. No one can tell a Negro that rich and poor are the same and that all can become rich. Close to the bitter realities of life, the Negro toiler in many respects is far superior in political and social knowledge, than the white worker who seems so far superior to him in technical and general information. Bringing, as he will, this rich knowledge to the ranks of the working class generally, the Negro, for this reason also, will be in the very vanguard of the working class.

The present period must bring with it the real organization of the Negro masses. More and more the old liberal individualism is disappearing and collectivism is taking its place. And the Negro masses will not be forever in the rear. Up to now, the various Negro organizations that exist have not been able to fill the bill adequately. The Urban League is more of a charity organization, or at best a mutual-aid society; the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People does not pay sufficient attention to the material interests of the Negro workers and does not believe that the leadership of the movement must be in the hands of the Negro proletariat and toiler, and that this is the class destined to change the world. The League of Struggle for Negro Rights has shifted the whole question to a demand for “land and liberty” showing that it is a mere “democratic” organization, rather than a proletarian one. Besides, the League of Struggle for Negro Rights is only a Communist Party affiliate; its whole purpose is to be one of the Negro “masks” with which the Party leaders can dance around and pretend to make an impression. As Stalinism has killed everything it touches, so must it kill the League of Struggle for Negro Rights as an effective labor or revolutionary organization.

Here, then, are ample reasons why the organization of the Negro Chamber of Labor is opportune and fulfills an historic need. Under the blows of the Roosevelt Administration which have rendered the lot of the Negro much worse relatively than before, such an organization has become an imperative necessity. The N.R.A. has carefully excluded from any of its provisions those occupations where Negro labor predominates. The majority of the Negro workers work as agricultural laborers or as domestics. Precisely these industries have been left untouched, so far as hours and minimum wages are concerned. Similarly, the A.A.A. has enormously deepened the crisis for the Negro sharecropper and tenant, rendering his life unbearably miserable. The present situation provides the immediate political and economic prerequisites for a mass organization of the type of the Negro Chamber of Labor.

The aim of the Negro Chamber of Labor is to be the militant trade-union center where all the Negro workers will be able to turn for help. Are Negro houseworkers and chauffeurs slaving away terribly long hours for practically nothing? Then the Negro Chamber of Labor will begin to organize these men and women and fight for their interests. Are Negro building trades workers discriminated against by the white trade unions? Then the Negro Chamber of Labor will fight to get them into these unions and to break down the color line. Are the Negro workers in the various factories doing the hardest work and getting the lowest pay? Is the Negro being discriminated against in unemployment relief? Then the Negro Chamber of Labor will see to it that these abuses stop.

Far from being a Jim-Crow organization, the Negro Chamber of Labor will see that the greatest possible solidarity between white and black sections of the working class becomes a tremendous reality. The best way to stop Jim Crowism is to organize the power of the Negro masses, to make that power felt and appreciated. Any swinishness on the part of the white workers can then soon be broken. Let us have no fear that the Negro masses will choose to become segregated and isolated from the great body of white proletarians.

An important task of the Negro Chamber of Labor must be the building of an inter-racial physical defense organization for the smashing of the lynching of Negroes and poor white toilers. What is wrong about lynching is not the act of lynching itself but the reactionary direction which lynching generally takes. Lynching is too old and important an American custom for us to scold at it like fishwives. We must use the direct street action of the masses for our own purposes. We must hail, for example, the action of the poor farmers in Lemars, Iowa, who recently threw a rope around the neck of a judge and threatened to lynch him if he permitted further foreclosures of their farms. It would have been a great demonstration had there been Negro farmers in the crowd. Certainly the Negro Chamber of Labor must not have any illusions that the Federal government is capable or willing to stop the lynching of Labor in the black skin. Labor itself will have to do this job, and can do this job only by direct physical action.

There is one further point about the Negro Chamber of Labor. It will be a place where Negroes can assume full charge and responsibility of important posts and work. In all the inter-racial organizations the Negro, of necessity, has been a minority and, willy-nilly, his opportunities have been limited in regard to leadership and responsibility for execution of policy. The Negro Chamber of Labor means to change all this. It will be a place where the Negro himself can step forward, develop his own genius and contribute his own experience in his own way, to the general labor and revolutionary movement. Whether the Negro will have his own republic in the Southland or not, is for him to say and for the white workers to support his choice no matter what it may be, but at least there can be one place established where the Negro, here and today, can declare, this is his own—truly his own— and where he can decide his leadership and his methods.

Let the Negro worker raise his head high. His day is coming.

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_1934-07_41_7/sim_crisis_1934-07_41_7.pdf