History is not dead, is not inert. It is alive with forces, living roots, which can be summoned today to give us perspective and succor. One of those often called on, especially in times of retreat and isolation, is the germinal French communist Gracchus Babeuf, whose name is itself an invocation of past powers, and the Society of Equals.

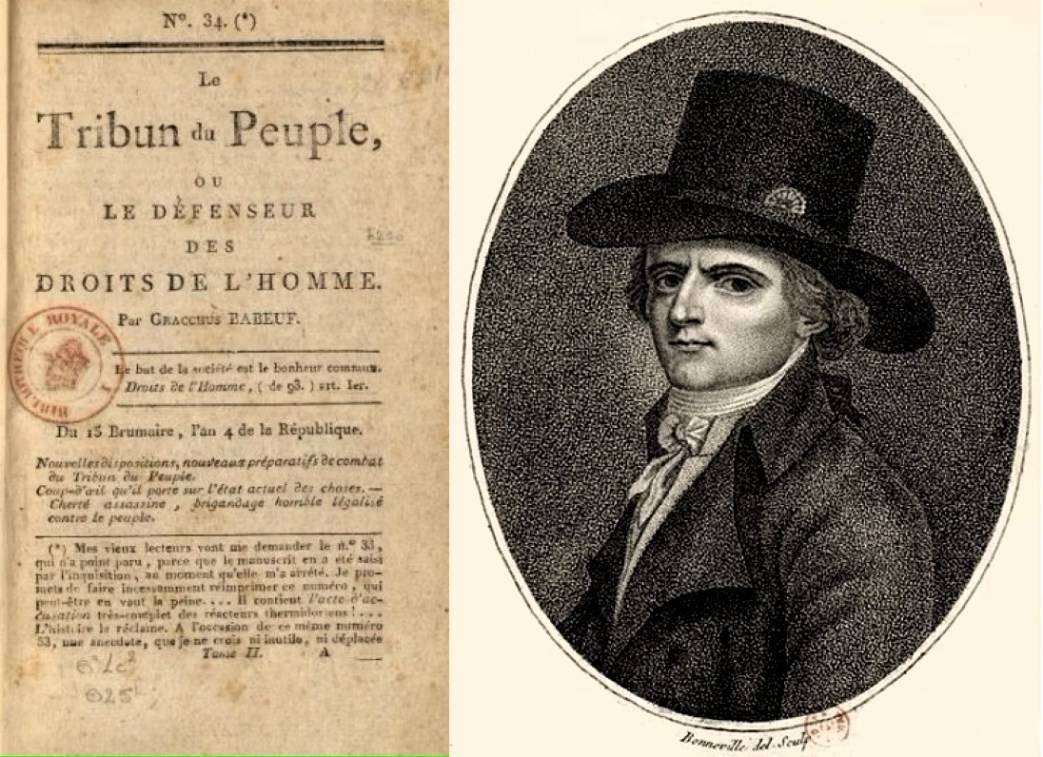

‘Gracchus Babeuf: The Organizer of the Society of Equals’ by Reva Craine from Young Spartacus. Vol. 4 No. 5. November, 1935.

To the casual student, the great French Revolution consists of the capture of the Bastille by the Parisian masses, the arrest and execution of the King, the Reign of Terror, the downfall of Robespierre and finally the coup d’etat of Napoleon Bonaparte. Those who view the Revolution in this light miss the essentials and overlook the basic forces at work in the Revolution, the class forces which impelled it, drove it up to but not beyond certain limits. The Revolution proper ends with the downfall of Robespierre. The reaction of the left wing to this event is rarely evaluated and the small movements, semi-socialistic in character, are never taken account of. Now, on the occasion of the 175th birthday of Gracchus Babeuf, a few words ought to be said about this almost unknown figure and his movement.

Francois Noel Babeuf (who later assumed the name of Roman, Caius Gracchus) was born in St. Quentin, on November 23, 1760. His youth is not of particular interest. His father, a tutor, died when Francois was a young boy and on his death bed, it is related, he urged his son to devote his life to the interests of the poor and oppressed. At the age of fifteen, he entered the service, as a junior clerk, of a land commissioner, who taught him land surveying. He pursued this profession up to and including the early period of the Revolution. During the opening days of the Revolution, he participated little in active political life although previously he was supposed to have prepared several papers on land distribution which contained the germs of communal ownership of land. In 1790, he published a radical journal for which he was arrested and later released. Again, in 1793, he was arrested, condemned to 20 years imprisonment and released soon after.

It was only after the downfall of Robespierre and the establishment of the Thermidorean government that Babeuf began to take an active interest in political affairs. At first, his own position was very confused–one day he attacked the Terror of Robespierre and the next he attacked the new government which was daily rescinding the rights granted in the Constitution of 1793. For his attacks upon the Thermidoreans, he was arrested in 1795 and thrown into jail. Not for the first time did jail serve as a “university,” for here in jail Babeuf met up with some old Jacobins who influenced his mode of thinking and supplied him with whatever revolutionary literature existed at that time. It was here too, that he began to give serious thought to the question of communication of the land and the products of industry.

It must be recalled at this time that the French Revolution was a bourgeois revolution, that is, the old aristocracy was overthrown and replaced by the newly arisen and rapidly growing bourgeoisie, the capitalist class. However, the first battles of the Revolution were fought, not primarily by the bourgeoisie, but by the masses of the people, the Parisian “rabble” who had hoped that victory over the fallen regime would guarantee the realization of the slogans of the Revolution: Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. But once the feudal regime was overthrown, the wealthier section of the bourgeoisie took the power into its own hands by overturning the government of the “terror” of Robespierre and established the government of the Thermidoreans (the overthrow of Robespierre occurred in the month Thermidor according to the calendar used during the revolution) and ruled in the interests of its own class. A new constitution was drawn up, the Constitution of the Year III, (according to the revolutionary calendar) which abolished universal suffrage, reimposed a high property qualification, created two governing chambers and executive body of five known as the Directory. The old democratic principles which had found their expression in the Constitution of 1793 were swept away by a stroke of the pen.

In the meantime, the living conditions of the people grew constantly worse. The sale of confiscated church and feudal land had benefited not the poor peasantry who had been clamoring for the land, but rather the speculators, those with ready cash who were able to buy up most of the land at a very low cost. The government had inflated the currency in order to maintain itself and the heaviest burden naturally fell on to the shoulders of the plebian masses. The price of bread and other necessities rose without bounds. The masses had made supreme sacrifices to achieve the revolution and in return they were rewarded with a new set of rulers representing an enemy class.

It was under these conditions that Babeuf founded his “Societ of the Pantheon,” a political club, whose program consisted of a series of demands calling for the compensation of those who had fought in the Revolution, application of the poor law, alleviation of the living conditions of the masses civil rights, and others of a similar class character. Babeuf, in his paper, “The People’s Tribunal,” denounced individual property-ownership as the principal source of all existing evils. Before long a new order for his arrest was issued and from then on he had to live in hiding. The Society was outlawed. In its place was substituted the Society of the Equals, led by the

“Secret Directory,” an illegal committee of insurrection, which was to prepare the overthrow of the Thermidorians.

The Secret Directory consisted of Babeuf, Debon Buonarroti, Darthe, and others. It aimed to destroy the new Constitution and to achieve political liberty and economic equality through the abolition of private property and the institution of a communist regime. Its manifesto said in part: “The French Revolution is but the precursor of another and a greater and more solemn revolution, and which will be the last!” and further on: “We aim at something more sublime and more equitable–the common good, or the communist of goods. No more individual property in land; the land belongs to no one. We demand, we would have, the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth, fruits which are for everyone!”

“Let disappear, once for all, the revolting distinction of rich and poor, of great and small, of master and valet, of governors and governed!” And finally, in a list of fifteen paragraphs, it summarizes its demands, stating that the new Constitution of the Year III is illegal because it was obtained against the will of the people and by shooting them down. The Secret Directory demands the restoration of the Constitution of 1793.

In addition, the Secret Directory prepared a document describing the new government which was to be established upon the overthrow of the Thermidoreans. The basic principle underlying the new society is the communal ownership of the land and of industry, equality before the law, etc. It goes into great detail describing the new regime, even describing where and how many storehouses should be built to hold the products of the common toil. The whole scheme was utopian because it sought to establish the new society overnight, the moment power was seized. Further, it could not understand the historic role of the new society, its economic and political nature; nor did it understand the basic political and practical problems of the rising proletariat as the new revolutionary class.

It is not particularly original, taken mostly from the works of the French philosopher, Morelly, who had previously advocated such a system. What is new in it however, is its declaration that the establishment of the new society is predicated upon the seizure of political power. from the hands of the ruling class.

The Secret Directory met regularly and discussed in detail the plans for the insurrection. It was decided that on a chosen day, when the masses were thought to have been sufficiently aroused by the agitation of revolutionists, banners would be distributed to the revolutionary agents and that in the name of the Insurrectionary Committee of the Secret Directory, a proclamation should be issued threatening the death of anyone carrying out an order of the usurpatory government:” Babeuf and his friends were to head the movement. Finally, after lengthy discussion, a manifesto calling for the general rising was prepared. It was entitled: “Act of Insurrection.”

But it was just at this moment, when everything was prepared for action, that the plan was betrayed, as so many other conspiratorial movements isolated from the mass es, by a government agent, Grisel, who had managed to work his way up to the Secret Directory. On May 10, 1796, the government swooped down upon the Secret Directory and arrested a large number. Ваbeuf and the others were put to trial lasted from February to May, 1797. The behavior of Babeuf and his comrades is a model of how revolutionists conduct themselves in the clutches of the enemy class. Babeuf and Darthe, especially, utilized their trials to make long, well prepared speeches to the public which was allowed to attend the hearings, explaining the program of their movement and urging the masses to resist every reactionary move of the government. Finally, a year after their arrest, Darthe and Babeuf were sentenced to the guillotine. As they were being led from the courtroom, they attempted to commit suicide by stabbing themselves. They did not succeed, and on the following day both, badly wounded, were carried to the guillotine and put to death.

Young Spartacus was first published by the National Youth Committee, Communist League of America (Opposition), in New York City. A semi-monthly from 1931 until the end of 1935. The Spartacus Youth Clubs and then the Spartacus Youth League would be organized and publish Young Spartacus before the movement entered the Socialist Party and Young People’s Socialist League in 1936’s ‘French Turn.” For must of its run, as with its parent organization, Young Spartacus was aimed at supporters and the milieu of the Communist Party and the Young Communist League of which it viewed itself as an opposition. Editors included Manny Garrett, Martin Abern, Max Shactman, Joseph Carter, and George Ray.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/youngspart/YS1935/nov1935.pdf