One things is a constant in capitalist society; its police are thugs and bullies. Here, an enraged Ralph Chaplin tells how a brutal riot of Chicago cops against the unemployed was portrayed as a ‘riot’ of the unemployed. Could have been written today.

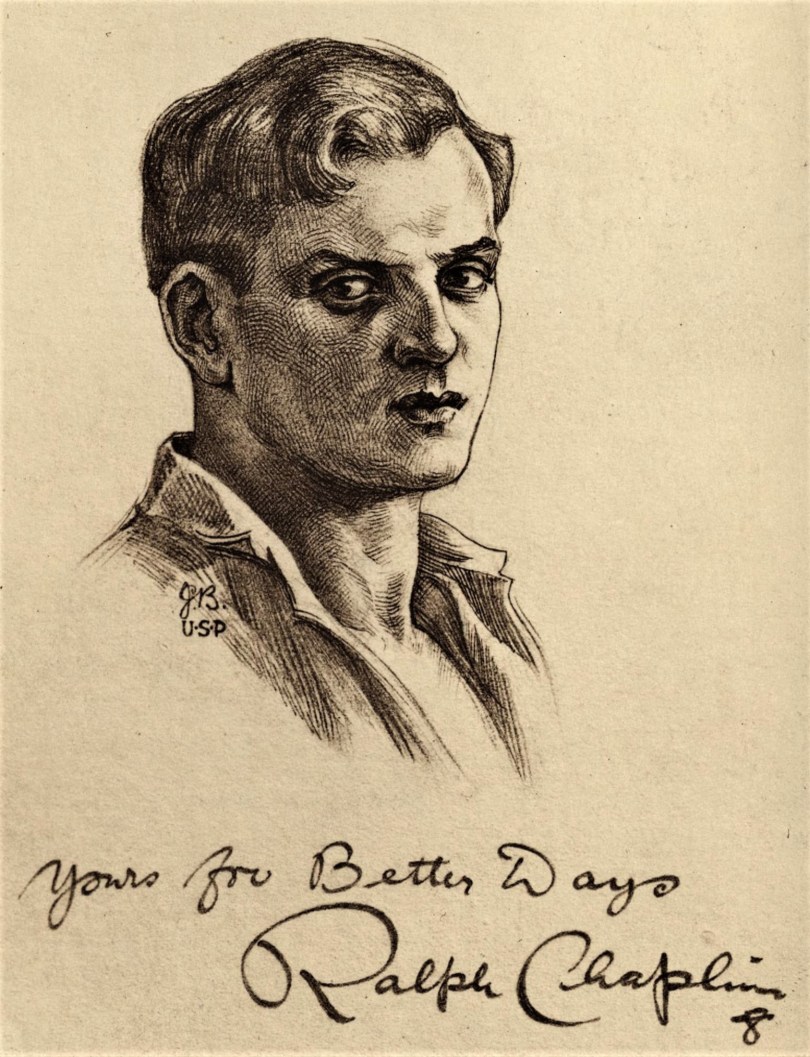

‘A ‘Hunger Riot’ in Chicago by Ralph Chaplin from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 9. March, 1915.

Sunday January 17, witnessed an heroic attempt on the part of the notorious Chicago police force to solve the “unemployment problem.” Strange as it may seem, the police are the only ones who have a clear and forcible answer to the question “what is to be done with the unemployed?’ Their answer is unmistakably clear—and forcible. “Society” was too busy at the autoshow or the wheat pit to have time to bother with such trifles as unemployment and hunger. The preachers were too busy praying, the politicians grafting, the reformers talking; and most of the radicals were too busy settling the war or devising ingenious formulas for future class fights, to have time to listen to the clamoring of jobless crowds of homeless, hungry men.

So the unemployed themselves decided to get together and command a little attention. This they did; and they got attention—from the police. You see the police force in Chicago is “in bad” with the “respectable” element of the city. It seems that instead of protecting “property” they have been surreptitiously sabotaging the same, and dividing the spoils amongst themselves. Consequently they were more than anxious to prove to the tax-paying community the inestimable value of the police system to the existing order of things. And thereby hangs a tale.

From what has occurred it is very evident that these uniformed bruisers of the master class desired and planned to start a “riot” and then get the credit for crushing it. In other words the “riot” would be merely the means to an end—a glorious victory for the lawful slug-shot and club and pistol. And then…some big-jawed, gorilla-framed troglodyte in uniform could have posed as a heroic defender of “Law and Order.” And the prostituted “Truth rapers” of the newspapers, eager to do with their scribbling pencils any dirty work left undone by the cossack’s club, would have convinced the world with their unholy chorus of acclamation. But this dainty bit of mediaeval conspiracy was too “raw” to be “put over” even in Chicago.

Sunday the 17th was one of Chicago’s typical winter days—a heavy, grey sky and a biting wind that went ravening through the dismal streets and around the tall buildings and the bleak and deserted factories. Bowen hall, at the Hull House, was the objective point, and from all the byways and alleys of the labor ghettoes came the crowds of hungry and jobless to the unemployed meeting. Through the bitter cold they came—men of all descriptions and all nations—all but the “barrel-house stiffs,” and these were too busy hugging the comforts of the big stove and the saw-dust box to trouble about such a needless and disagreeable thing as work. Through the icy streets they came in hundreds, and past them hurried smug Respectability, cuddled into its overcoat or motoring carelessly along in the plush-padded, rose-scented luxury of the Limousine. It was a polyglot crowd that crammed the big hall, and one really representative of Chicago’s unemployed; Slavic and Latin laborers, wintering migratories and white-collared “stiffs,” still proud and dreading the plunge into the yawning depths beneath them. Here and there too, were the red, beefy faces of the “gum-shoe” thugs, watching the jobless crowd with cat-like care, and waiting uneasily for the signal to spring the plot that was to cover them with “glory”—the plot that was to punish men for the crime of being hungry.

The meeting was orderly—even apathetic. The audience seemed pitiably glad to find a little warmth for their blue faces and stiff fingers. Back of the speakers’ platform was a big black banner with the word HUNGER on it in white letters. Throughout the hall were pasteboard placards bearing such inscriptions as: “We want WORK; not Charity,” “Why starve in the midst of plenty,” “Hunger knows no law,” etc. The speeches were made almost without exception by members of the unemployed—many of them by men from the audience. The general drift of these “speeches” was a denunciation of the crumby “flop-houses,” bread-lines, soup kitchens, Mission “dog kennels” and the like. It was asserted that organized charity in Chicago is admittedly inadequate, and that, even if this were not the case, soup is no substitute for employment and the right to earn a decent living. The most radical speaker was Mrs. Parsons and the most radical thing she said was this: “The only property working men possess is their own bodies, and they should guard and protect these bodies at least as jealously as the masterclass guards and protects their possessions.” She also said that “as long as the capitalists can throw their cast-off rags and a few crusts of bread at the working-class in the name of ‘Charity,’ just so long will they have an easy and cheap solution for the problem of unemployment.” As a whole the speaking was far from fiery, and the audience was anything but boisterous.

A young Russian by name of Barron, after stating that Kansas had produced grain enough for the United States, closed the meeting with the pointed remark, “I am a baker and I am expected to starve because I cannot get work baking the bread you people need and cannot buy.” He then went on to ask the crowd if they were content to slink out of sight and suffer privation and hunger without a protest and to accept charity rags for their backs and charity soup for their bellies deluding themselves all the while with the idea that such things were the equivalent of labor and the right to live like men. A short time after this the audience voted unanimously to parade and to show to the smug and respectable the rags and suffering they never care to see or think about.

And so they streamed from the hall down into the cold street again, with the black Hunger banner in the lead. But the invisible minions of the “law” had passed their signals. The sluggers were already clutching their “billies,” the squads of detectives and mounted police were in their places, and the ambulance was waiting around the corner for the finish of the work the strong-arm degenerates of Capitalism were about to do!

Down the street started the parade with a few men and valiant girls and women grouped about the black banner in the lead. There was no shouting, no cheering or undue excitement,—nothing that even remotely resembled the starting of a riot. Just pinched faces—blue with the cold, tightly buttoned rags and, if anything, indifference—they might just as well parade as not, having nothing else to do. And that parade would have been quiet and undemonstrative to the end. That crowd hardly had the spirit to protest—let alone fight! They went forward into the police trap like lambs to the slaughter.

The procession had scarcely turned the corner onto the main street when, without a word of warning, a gang of plainclothes thugs set upon them with leaden “billies,” smashing blindly—right and left, through the crowd. The purpose of the attack by these murderous gutterrats seemed to be to cut the parade in two —to cut off the head, so to speak. These were followed by other burly red-faced, well-dressed brutes, who rushed everyone in sight, sprawling the hungry men in all directions with their fists. Still others followed, with drawn revolvers, firing over the heads of the crowd in order to drive it back into the street from which it was emerging. And that sight I shall never forget; the bestial faces of those low-browed sluggers—distorted with the blood lust, the smashing of fists into faces blue and pinched with cold, and the sickening crash of dripping slugshots on the heads of defenseless men, the. spurt of blood over hands and clothing and pavement stones. Is this the only answer, I wondered, of the Powers that be to workingmen who question why they should go jobless and cold and hungry in the midst of plenty?

But even this unexpected attack from the cowardly ex-second story men of the plain clothes force did not stop the parade. It swelled up around them and over them leaving them somewhat the worse for wear. And the determined paraders rejoined the tattered hunger banner at the head of the procession and marched for almost a mile, many of them singing all the way in spite of torn clothing and bloody faces. Finally a goodly reinforcement of uniformed police met, manhandled and pinched as many as possible, and the mounted Cossacks clattered down the streets and sidewalks driving the paraders pell-mell before them. Soon the affair was all over save for the lying in the newspapers.

Two weeks later, after attorney Cunnea had proved to Judge Gimmel of the criminal court that police interference in an orderly parade was unconstitutional, another unemployed parade was attempted—successfully. This time a procession over a mile long and with a Hunger banner in the lead, wended through the cold and drizzle and slush for about five miles under the towering sky-scrapers, past the swell hotels and theaters in the heart of the city and through the streets and boulevards, returning at length to the hall from whence they had started. And the paid skull-crackers of the police force, who had predicted ‘riot’ were chagrined and disappointed—nothing happened to give them a chance to exercise their talents—nothing but the singing of revolutionary songs; and coppers are not usually talented vocally. Besides, they could not have sung had they so desired; it’s against the regulations to do anything as harmless as singing while on “duty.”

As it is up to the working class to solve the ‘problem’ of unemployment, any efforts along that line are deserving of encouragement. No intelligent person claims that parading is a panacea for unemployment. But the instinct of solidarity that actuates a body of workers to go after something they want and get ît is a good thing—even if they only get the right to parade the streets and startle respectability from its indifference and smug complacency. The solidarity of the protest parade is apt to be a foretaste of the solidarity of the shop. Thousands of unemployed have been made rebels for life by the lessons this one bitter winter has taught them. They will be rebels on the job, too, when they find jobs. The parade is a good thing when nothing BETTER can be done. When masterless slaves decide to get together and show their condition to the public—when they meet together, discuss their miseries together, march together and sing together, they are tasting solidarity. And such action may help to jolt their brothers on the job into some kind of mass action in behalf of the working class as a whole. Solidarity spells emancipation. “Better any kind of action than inert theory.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n09-mar-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf