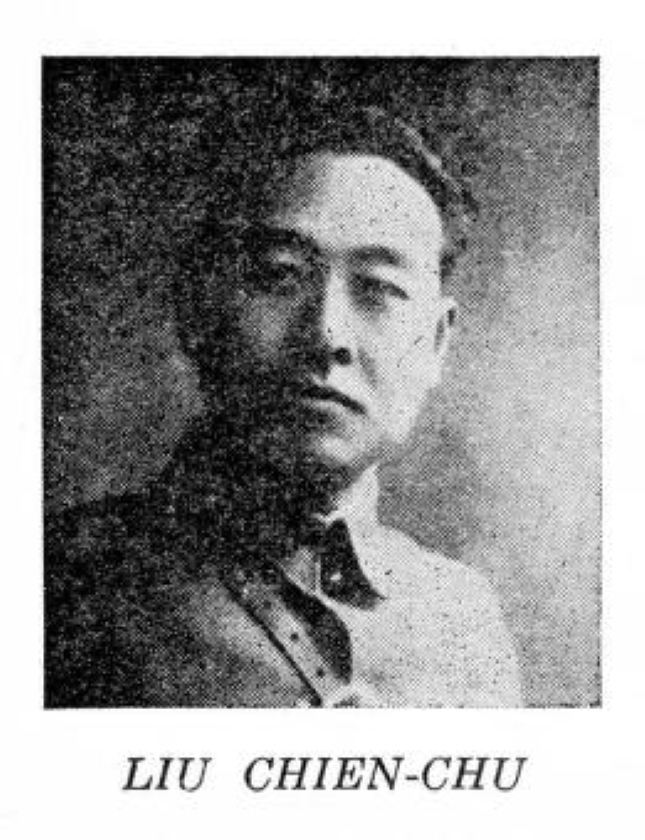

‘The Death of Liu Chien-chu’ by the Left Writers League of China from New Masses. Vol. 7 No. 3. August, 1931.

Liu Chien-chu, one of the most capable of Chinese Communist-peasant organizers, was born in Ping-tu District, Shantung Province, in 1896, of a peasant family. He was able to get an education through the missionaries and throughout his early life was a Christian. He attended the missionary Middle School in Tsinan but, because of poverty, could not go to a university. For a time he became a soldier. Because of a thesis which he wrote, he won a scholarship in Yenching University, near Peking, President Stuart offering him either money or a scholarship. He studied and graduated from Yenching after thr6e years. His subject was history.

When the May 30th, 1925, massacre took place in Shanghai he became an important members of the Federation of Student Unions of Peking, and was President of the Yenching University Students’ Union. Graduating in 1926, he was recommended by President Stuart to become a teacher of Chinese in the Christian Middle School in Chenkiang, Kiangsu Province, where he taught for one year. Despite this good position and the request of students to remain, he went to Canton, thinking he might become active in the revolutionary government there. For six months he taught in the Middle School of Lingnan University, then called the Canton Christian College, but left this because he had become a Communist and could no longer remain in a Christian institution. Requested by his students to remain, he refused, telling them frankly his viewpoint.

From Canton he went to Wuhan and joined the Political Bureau of the Eleventh Army, where he worked for five months. The Communist Party and the Kuomintang still cooperating, he was sent by the Peasant Department of the Kuomintang to Honan as a peasant organizer. When the Kuomintang and the Communist Party split and the white terror began, Liu, with other Communists, escaped. From that time on down to May, 1929, he worked with the peasants fighting and organizing peasant unions. In May, 1929, he was captured in Shantung Province, his native place, and given a secret trial before the militarists there. The chief witness against him was a former friend, a Kuomintang member, who offered him a high position if he would betray his comrades and Party and become a member of the Kuomintang. Liu’s reply was a speech in which he uncompromisingly stated his convictions as a Communist. Pending a decision in his case, he was tortured to make him betray his comrades. He was put in a wooden cage about three feet high in which he could never stand up or lie down, and about his ankles were 20 lb. shackles. His hands were shackled and attached by chains to his ankle shackles. He was permitted to leave the cage once a day to go to the toilet. After months of this torture, in which he nearly died, he was finally released, still uncompromising in his convictions, and was sentenced to eight years imprisonment. He was put in the Tsinan First “Model” Prison, in a cell with six other men, all Communists. He, like they, was always shackled with the 20 lb. iron bands and with wrist bands attached by chains to his feet. The cell was dark and damp and the prisoners were permitted to leave their cell for ten minutes each day to go to the toilet.

Books sent to them were severely censored and nothing of a political nature could be had. The New Masses of New York got by because it was in the English language. The only kind of social novel to get by was Upton Sinclair’s Love’s Pilgrimage , and this because of its title. Liu spent the last days of his life translating this book into Chinese, but death interrupted that.

The manner of his death is important — it was due to the rivalry between two militarists. Chiang Kai-shek, the chief Nanking militarist, tried to force Han Fu-chu, military governor of Shantung Province, to take his troops and go to Kiangsi for the “Red Suppression” Campaign. Han Fu-chu knew this was a move to dispossess him in favour of a Chiang Kai-shek general. So he replied that he was so busy suppressing the Communists in Shantung that he could not go to Kiangsi. He had no proof, so he presented proof. His first “proof” came on the Sunday morning of April 5th when he took out 22 political prisoners from Tsinan prison and shot them to death. All had already been sentenced to long years of imprisonment. Among the victims was Liu Chien-chu, who had served some two years of his term. After this, the foreign and Chinese press carried a few lines saying that Han Fu-chu had executed 22 bandits recently captured in Shantung.

Liu Chien-chu was one of the most capable of Chinese revolutionary leaders. He was a North Chinese with the nature of the North Chinese. He studied slowly and seriously and fundamentally, was slow to reach a decision, but once convinced, nothing could move him. Communism was a part of his life and thought. He was not only a man who studied much, but be was cool in judgment, a marvellous organizer of great influence among his own class — the peasants. He lived with them, organized them fought with them in uprisings against the reaction and the white terror. At any moment he could have betrayed and won high position with the Nanking Government. But he did not. He, one of the most capable of Chinese revolutionary leaders, remained faithful to his convictions and to the revolution — faithful through torture and into death.

Shanghai, China LEFT WRITERS LEAGUE OF CHINA

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1931/v07n03-aug-1931-New-Masses.pdf