As Nearing notes, no difference was more dramatic between U.S. and the new Soviet schools than student autonomy and self-organization.

‘IX. Organization Among the Pupils’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

IX. ORGANIZATION AMONG THE PUPILS.

Soviet schools are doing important experimental work with subject-matter and method. Probably the most tangible product, to date, of the new program, is the organization of pupils in the schools. Before the Revolution organizations among the pupils were ordinarily forbidden by the state. Today they form an essential part of the educational system. It is through the student organizations that the pupils in the various school grades are learning how to live and work together.

The experimentation with subject matter is confined, largely, to the elementary schools. New methods of instruction have been applied generally in the elementary schools, and to a degree in the higher schools. But the organization of students existed, in some form, in every school that I visited.

Student organizations in the Soviet Union are four chief kinds: (1) Organizations that are designed primarily to carry on student activity, such as sport and publications, to maintain the discipline of the student body, and to give the students a share in the administration of the schools. (2) Organizations of pupils to control and to help direct academic work. (3) The economic organization of pupils, either in co-operatives or in trade unions. (4) Political organization of pupils, either in Pioneer groups or in Young Communist groups. All of these organizations are being built up with the assistance of the school authorities, who are experimenting to discover how far children are able to go in the direction of social activity.

Something has already been said about these different forms of student organization in the chapters dealing with the different grades of schools. Here it is possible only to make a survey of the tendency and to give some indication of the theory that underlies this branch of Soviet educational activity.

No school that I visited in the Soviet Union was without its student body organization or organizations. In the one or two room village schools, this organization was quite rudimentary–a mere gesture. In the larger village schools it was well under way. In some of the city schools, it had reached an advanced stage of development.

There was no single form of student organization. The plan was general. Its application differed with the differing needs of each locality. Its more important variants were:

1. In the degree to which each class was organized.

2. In the relation between class organization and the organization of the pupils in the entire school.

3. In the closeness with which teachers were expected to watch and to supervise student organization and activity.

4. In the relation between student organization and the actual work of administering the school.

5. Of course the extent and complexity of student organization varied directly with the age and advancement of the pupils. It was negligible in the early elementary grades. In the higher schools it was a determining factor.

6. In the proportion of student representatives to teachers on the various committees and governing boards.

Class organization was more prevalent in lower schools than in higher schools. In the elementary grades, most of the students were organized, first by classes and then as a school. In the higher schools, on the contrary, the trade union group and not the class was the unit of organization. Students were organized first in their student unions and then as a school.

The simplest form of class organization consisted in the election of a secretary or of a small executive committee, to take the roll, to keep order, and to tidy up the room. The next stage involved the appointment or the election of a number of sub-committees, each with a special task to perform. A still more complicated form of class organization consisted of the division of each class into a number of sub-groups of six or eight or ten pupils, and the joint work of these sub-groups. This last plan I saw worked out in one of the schools in the Donetz Coal Basin.

Children of eight to ten years were divided into groups of six. A class of 30 children would thus contain five groups. From 11 to 15 years, the pupils were grouped in tens. Among the younger pupils, each group of six selected a leader, and these leaders made up the class executive committee. Among the older pupils, however, each group selected three of their number: (1) was a member of the class executive committee; (2) was a member of the class culture committee; (3) was a member of the class sanitary committee. This method provided three committees of three members, but all elected in small groups.

Generally the student executive committee was charged with the handling of discipline and with the supervision of class affairs. The culture committee secured and distributed reading matter and was responsible for the publication of a wall newspaper, when one existed. The sanitary committee was sometimes charged with the duty of keeping the room clean, sometimes with the duty of seeing that the pupils kept clean, and sometimes with both tasks. In this Donetz Basin school, the sanitary committee was expected to keep both school room and pupils in sanitary repair.

Student organization throughout an entire school ordinarily involved either the calling of the whole student body together, and the election of executive officers; the election of delegates, from each class, to a delegate body charged with the duty of selecting an executive, or the election, by each class, of a member or members who, in the aggregate would make up the school executive organization. The elections were usually held quite frequently to give the pupils a chance to modify their decisions.

Once constituted, the executive committee divided itself into a number of sub-committees and very frequently drafted other students qualified to serve on these sub-committees. The committees most generally met with dealt with sanitation; with the supplying of the economic needs of the students; with culture the school wall newspaper, the reading-room, the library; with the portion of school work to be done by the students; with the management of the student club and club-rooms. Occasionally there were other committees appointed, particularly in the higher schools where there were special needs. Either the class executive committee or the executive committee of the whole school dealt with discipline.

Control of these student committees and subcommittees was ordinarily in the hands of the students. Occasionally teachers were appointed to supervise committee work, but this was exceptional. In all cases, the school administration kept in touch with the student activities in the same sense that they kept in touch with the progress that the students made in any of the problems that they were studying. Self-government is a part of the course of study, and as such it comes under the observation of the school authorities.

I talked with one boy who was a member of the student executive committee in a factory school. The entire student body, in that school, met and selected an executive of twelve members. The executive appointed: a sanitary committee that had charge of personal, school and home hygiene; an industrial committee that supervised the conditions under which the students worked in the factory; an editor for the wall newspaper of the school, and a committee on the conditions of student life. Some of these sub-committee members were members of the executive and some were not.

“What would you do if a boy smoked in class while the teacher was away?” I asked.

“That is against the rules of the school,” the lad replied.

“He would be told by the class monitor to behave himself.”

“Suppose he refused to stop smoking when he was told to?”

“Then the case would go to the student executive committee.”

“But suppose he still smoked in class?”

My informant seemed a bit put out. “We never have such a case,” he said, “but I suppose that if we did we would take the matter up with the Pioneers, if he belonged to them, or to the Young Communists, if he belonged to them. We might also take it up with the Factory Committee. We certainly would not let the matter pass. There is no such thing as a school without discipline.”

Interestingly enough, this lad never even suggested the possibility of beating up the delinquent. His whole method of discipline consisted in bringing social pressure to bear on the offender.

This system of organized social disapprobation is relied upon quite generally by the students. It seems to be wonderfully effective. So far as I could learn, physical punishment is quite rare. I did not find a single case where it was used or even suggested, although the student leaders with whom I talked all declared their chief problem to be that of discipline.

School boards or committees are divided into two general classes: school committees or councils, having general control over the affairs of a school, and consisting of a relatively large number of representatives from teachers, students, technical workers, parents, trade unions, and political organizations. The second class consists of small school executive boards, usually from five to seven members. The general school committee meets rarely–once a month or once in three months. The executive board meets frequently. In every school that I saw, the students were represented both on the general committee and on the executive committee.

Technical workers (janitors, clerks, and helpers about the schools) were almost always represented on the general committee and rarely on the executive committee. Trade union representatives were almost always on the general committees and almost never on the smaller executive committee. Parents were frequently represented on the general committee, but seldom on the executive committee. Political representatives (Communists, Young Communists) were almost invariably on the general committee and almost never on the executive committee.

Literally, therefore, there was not a single school that I visited in the Soviet Union in which the students did not take part in the management and administration of the institution. Practically always it was a minor part. In the lower schools it was probably more or less formal in a great many instances, depending, of course, on the personalities at the head of school and of student affairs. But in person, if not in influence, students were always on the governing boards.

Student participation in the direct control of academic work was largely confined to the higher schools. The elementary teacher was expected, at all stages in the development of the work, to talk over the plans with the children. In the lower grades, particularly, the range of choice left to the children must be quite small. The formal organization of student participation in the control of academic work began in the factory schools and in the later years of the other professional or high schools, when the students are 15, 16 or 17 years of age. In the higher technical schools some form of the subject commission was in very general use a series of committees, one for each chief division of academic work, on which faculty members and students (usually in the proportion of two or three to one) determined the character of academic work and supervised its execution. In all of the higher schools that I visited, the students played an active role in the control of academic work.

Economic organization of students existed from the lowest grades. There the organization took the form of tiny co-operatives established by the students, with the aid of the teachers, for the purchase of the supplies that the children needed. In the professional and higher technical schools the students have organized co-operatives for many different purposes. They have also quite generally organized trade union groups, which are made the basic unit for student organization in the higher technical schools.

Student members of trade unions usually pay one per cent of their income as dues. In the case of many students in the higher technical schools, a part or all of this income is provided by the union,–still the principle of dues payment is established. Students have joined the union, and are working and thinking in terms of trade union activities before they leave school.

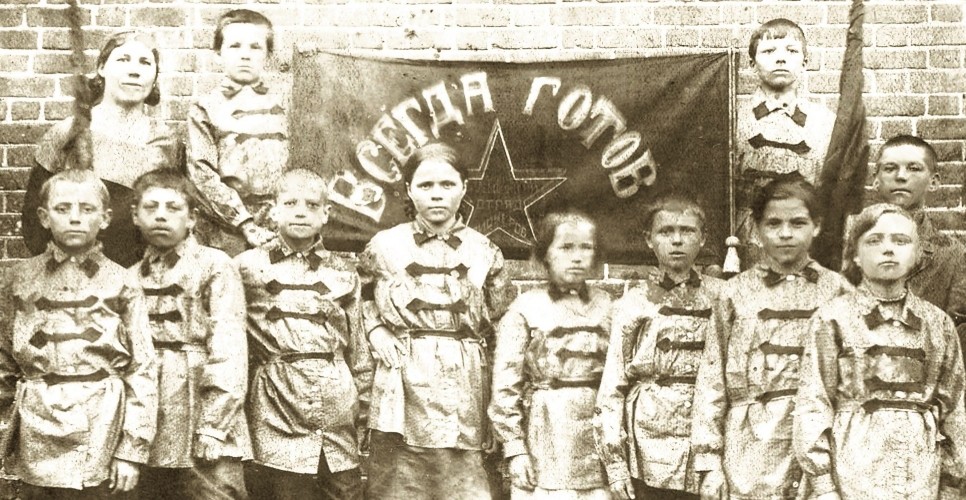

Many of the students in the Soviet schools are organized politically. A few of them are members of the Communist Party. Among the older students, a large number belong to the Young Communist organization. Younger students are organized into Pioneer groups. While the Pioneers is not in any sense a political organization, it is under the direct control of the Communists and Young Communists.

The organizations of Pioneers are not unlike the Scouts in their emphasis on clean living, exercise, out of door activities, social obligations. There the likeness ends. The chief object of the Pioneers is political and social education. The leaders of the Pioneers are seeking to develop a revolutionary spirit in their charges, and to train boys and girls who will play a part in building a Communist society.

Educators in the Soviet Union are studying student organization just as they study any other problem in pedagogy. Zaloojny, Director of Pedagogical Research in the Kharkov Department of Education, described the experimental and research work that they were doing in this field:

“Child study has been shifted from the child as an individual, to the child as a member of a social group,” he said. “This necessitates a complete change in the approach to the child problem.

“Under our system of pedagogical research, a normal child is one who is successful in group life. Any child who functions well in a group we classify as normal. All other children we classify and treat as abnormal.

“The normal child is therefore studied under the general heading of ‘social psychology’ or the psychology of social beings, acting in groups. The other children are studied under the heading of individual psychology, or, as we are now calling it, ‘reflexology.’ This corresponds with the field that you describe as ‘physiological psychology.’”

Zaloojny then took me to one of the pedagogical laboratories in which reflexology was being studied. There were four of these laboratories in the Ukraine. A few of the experiments were being made with animals. Most of them were carried on with some group of sub-normal children–feeble-minded, deaf-mutes, blind, and other children who were “incapable of normal group life.” The experiments consisted in stimulation with light, with sounds of various kinds, with food and with electricity. The effects on the actions and on the secretions were noted and tabulated.

The real work of pedagogical research in the Ukraine is not being done in these reflexology laboratories, but in the study of child associations. A detailed investigation is being made of the associations which children form in their games, their school classes, etc. Teachers are expected to stimulate and direct the desire for group organization in the same sense that they are expected to stimulate and direct the child’s interest in science.

When I was in Kharkov a questionnaire had been distributed, and about 800 children’s groups were under observation. As a result of their study, to date, they had slightly modified MacDougall’s classification (there point of departure) and were working with the following five forms of child collectives:

1. Brief collectives, organized usually before school age, and for the purpose of play. Of very short duration.

2. Self-organized collectives, more or less permanent. Usually organized to carry out a project of common interest to the group,–to build a house, make a raft.

3. Temporary collectives, but, for the period of their duration, developing a system of social machinery,— the club or meeting, with its officers and rules of procedure.

4. A permanently organized simple collective, having in view some specific purpose. A literary society.

5. A permanent complex organization for general social purposes. A student social club or fraternity.

The questionnaire called for the study of four sets of facts regarding each of these collectives:

1. The social background of the children; homes from which they come; school life; general social experience.

2. Situation under which the organization arose.

3. Stimulus that brought it into being:

a. Stimulus from inside the group of children.

b. Stimulus from outside the group.

4. Reactions (results) of the operations of the collective. Duration; reactions on the group life; development of other collectives.

“Have you found any standardized type of organization among the school children?” I asked.

“Not as yet,” Zaloojny replied. “That is just the point we are trying to settle. We want to find out whether there is not some form of organization that is peculiarly suited to the needs of each group of children. As we discover the most workable types, we shall try to have them adopted.”

“Will these forms of organization be adopted voluntarily by the children in all of the elementary schools?”

“By some groups, yes, of course. They already have their types of organization with which they are experimenting. Among the more backward children, and especially in the smaller villages, the organizations, will, of necessity, be introduced and encouraged by the teachers.”

One fact had already been generally observed: the children tended to make their organizations more complex and elaborate than the needs of the piece of work in hand required. Some of the children had learned this by experience and were going back to simpler forms. In the future, such mistakes could be avoided by pointing out the results of past experience to the children. The general idea underlying this effort to establish organizations among the school children was stated by Krupskaya in her message to the Young Pioneers:

“Normal children, living under normal conditions, seek to organize themselves…A definite objective, a collective life are the essential conditions for the development of children.” (From a multigraphed copy distributed by the Education Workers’ Union of the Soviet Union.)

The educational principles behind student organization were thus stated by the Scientific Pedagogical Section of the Russian Republic State Council of Education:

“1. The bourgeoisie places before the school, as objective: raising a citizen who is docile, and little disposed to change the essential forms of the established order. This object determines the character of the work and the internal structure of the school…

“In such a school the instructor plays the part of an absolute master over the class and over the students. system of punishments and other devices are added,–among them rewards, that are aimed to assist the instructor to reach the desired end. The children are at his mercy. He may double the tasks; he may send children from the class; in him the children see the enemy that must be fought. They struggle against his rules, violate them deliberately, form groups for this purpose. The teacher is the representative of state power, and in fighting against him, the pupils are fighting against the orders of the state. Such a struggle unifies large groups of students, weakens the prestige of the authorities, interferes with the realization of the educational objective, arouses a spirit of discontent, intensifies the hostility.

“The introduction of student autonomy in such a school has for its object the elimination of the struggle between teachers and students, to raise the prestige of the teacher, to place upon the children themselves the duty of surveillance, the execution of the teacher’s decisions, which is merely a means of subjugating the pupils to the teacher.

“2. In countries where bourgeois democratic republics are solidly established–America, Switzerland–one frequently finds in the schools an autonomy of another type. All at once or gradually, there is introduced into the school a constitution like that of the bourgeois democratic republic, with all of its attributes: elections, courts, even prisons (see, for example, the George Junior Republic in America). Pupils, particularly adolescents, enjoy a certain liberty of action under this constitution. Such student autonomy has for its object to raise citizens devoted to the bourgeois republic.

“3. The difference which exists between the objects that we propose for the school and those that the bourgeois state proposes, exercise a decisive influence on the form and the object of student autonomy.

“4. The object of our school is this: to raise a useful member of human society, joyous, vigorous and able to work, alive with social instincts, accustomed to organized activity, understanding his place in nature and in society, knowing how to relate himself to the march of events, a firm defender of the ideals of the working class, an able constructor of communist society.

“5. In our schools, self-government is not a means of governing the students more readily, neither is it a practical method for studying the workings of the constitution. It is a means by which the pupils may learn to live and to work intelligently.

“6. The richer the content of student life, the more thorough will be the student autonomy. Collective work is, par excellence, the great organizing force. Self-government cannot develop well, and take on the most rational and most helpful forms except in a school where collective work represents the vital nerve of the whole student life.

“9. Under its developed forms student self-government must include the union of educational groups and social activity which in effect embraces the economic, recreational and artistic work of the students, as well as student mutual aid. The students must in all cases be represented on school committees.

“10. The whole work of self-government must be handled by the pupils in co-operation with the teachers. The duty of the teacher consists in actively contributing to student autonomy. However, he will leave the scholars completely independent and will try not to let his authority weigh upon them.” (From a multigraphed copy of the official order, distributed by the Education Workers’ Union of the Soviet Union.)

Judging by what I saw in the schools, I should say that this general principle of student self-government was being carried out with reasonable fidelity by the local educational authorities. It is an educational principle of the highest importance, introduced for the first time on a large scale in a public educational system. Students are to be taught to work in groups, not so that the teacher will have an easier time, but in order that the students may have the social education that comes with group activity. Among all of the experiments that the Soviet educators are carrying on, this promises to constitute the most drastic departure from the educational system that exists in other countries.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf