Years before the sit-downs, Flint auto workers were in the vanguard, with the first full-factory strike in the industry as 5,000 Fisher Body plant workers organized by the T.U.U.L.’s Auto Workers Union struck in 1930.

‘Flint Strikes Fire’ by Robert L. Cruden from Labor Defender. Vol. 5 No. 8. August, 1930.

FOR the first time in American auto history all the workers in a single factory have walked out on strike. This happened when 5,000 Fisher Body workers in Flint, Mich., struck against a 50% wage cut and intolerable conditions.

The spirit behind such solidarity soon showed itself in strike activity. Accepting the leadership of the Auto Workers Union they organized mass picket lines which cowed even the police and the factory was closed down. A strike committee of nearly 120 was elected, each department in the plant having representation. A committee for strikers’ relief was formed. The women formed themselves into a “shock brigade” for picketing and parading.

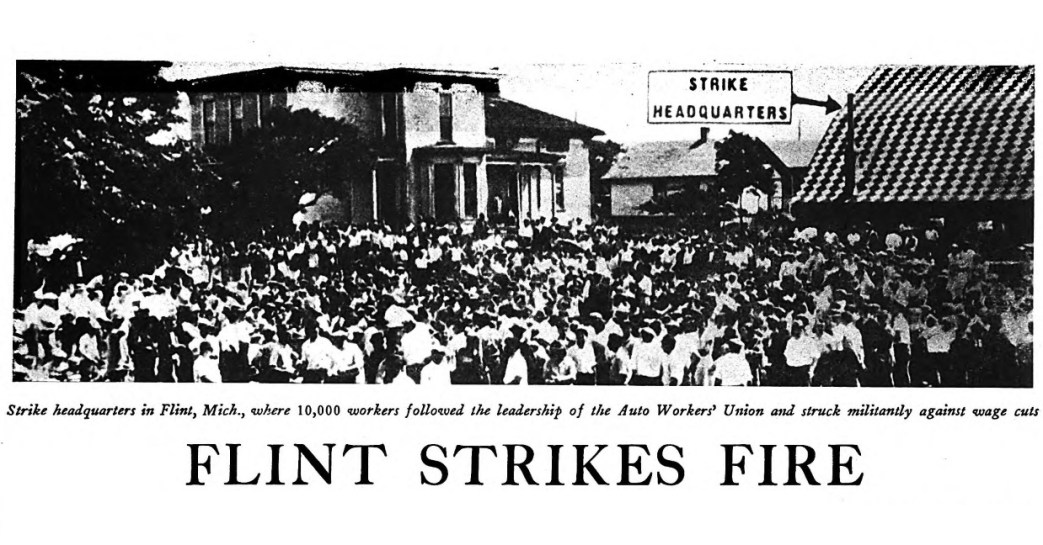

It was this brigade which led 10,000 strikers and their families into the downtown section of Flint in one of the most militant labor demonstrations in this state. After futile attempts to stem the strikers the police gave way and left the streets in possession of the workers. Police were hastily organized to stop the paraders from surrounding other plants but they might as well have tried to stop the sea. 400 girls from the A-C Spark Plug Company joined the strike and Buick sent representatives promising strike aid if the Fisher strikers would hold out.

Flint, General Motors town, was paralyzed. Not only were the strikers gaining support throughout the city but workers in other plants were actually planning to join the strike. Fisher Body officials were wondering whether it wouldn’t be best to surrender to their own strikers rather than have a whole townful of the strikers against them–and then General Motors and the police began their “red scare.”

Denouncing the strike as being due to “Communistic agitators,” the police swooped down on every militant striker and put them in jail without charges, holding them incommunicado. The chief of police told the strikers, “they will receive no more consideration here than Reds do anywhere in the country.”

With this encouragement the cops blackjacked and clubbed picketers. Meetings were smashed with club and gun. Mounted police did their usual “best” by riding down women and children. Without “legal” warrant the strikers’ headquarters were closed by police and strikers refused admittance. Those who protested got clubbed. When several hundred strikers decided to meet anyway they were set upon by squads of city and state police. Many were injured as a result of these fights. The strikers were driven out into the country, all the while harassed by cops. All this was “illegal” on the part of the Flint police–but one striker put it neatly. “We workers ain’t got no rights,” he said.

All this didn’t make the strikers go back to work. It merely stiffened their resistance. It was then that the stool pigeons got in their work. Tipping off the police they had every militant arrested–there are 57 strikers in jail now–and then they engineered a plan whereby “outsiders” were ousted from participation in the strike. A member of the strike executive told me that this was done by the stools on the strike committee holding a meeting of their own and passing this resolution.

The stools then went ahead, with the cooperation of Flint Federation of Labor officials, to form a union for “blue-bellied Yankees” called the Flint Automobile Workers Association. Hailed by the police as “the most hopeful sign since the beginning of the trouble” this union called off mass picketing, came out for only “lawful” activities, and, in the words of one of its officials, aimed to “get the goodwill of the police.”

The ranks of the strikers were thrown into confusion. Their trusted leaders were in jail. They were inexperienced in strike strategy. Their only guide, The Daily Worker, was destroyed as soon as it reached town. A member of the strike committee charged the new “union” officials with this!

In spite of this the rank and file carried on picketing, working under continuous attacks of clubs and horses. National Guardsmen were mobilized. Scabs marched to work under heavy guard. The strike was being broken from the inside.

Among those still out there is no sign of weakening, no moaning about “lost wages.” Their bitterness is now finding its true cause the stool pigeons. No striker with whom I talked but was conscious of the fact that the strike was being betrayed from within. They were angry because they had allowed the reds to be put in jail. “If they were reds, then I’m a red too,” was a common comment.

I did not have to talk of the I.L.D. The strikers already knew the initials. They told me of the activities of the I.L.D. representative and how he had evaded arrest for two weeks. The police got him when he spoke at a picnic of the strikers. The Daily Worker was praised, as was also the Auto Workers Union.

“We may have lost this strike,” a member of the strike executive said, “but we’ve learned our lesson. The cops are on the side of the bosses. So’s the law. We can’t meet. We can’t speak. The reds were right. They were the only fellows who put up a fight with us and stood the gaff. We’ll strike again and we’ll know better. Our only friends are the reds.”

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1930/v05n08-aug-1930-LD.pdf