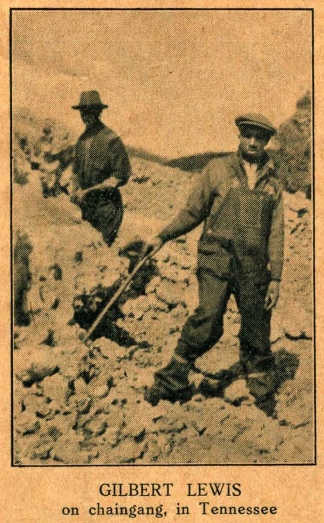

Gilbert Lewis, himself released from prison by an International Labor Defense campaign, on its 4th National Conference. While only active in the Party less than five years, Lewis, born in New Orleans in 1904, quickly became a leading Trade Union Unity League organizer based in Chattanooga, Tennessee where his work organizing unions and share-croppers ran him afoul of the racist powers, and he was constantly harassed and arrested, but continued his work. By 1929, Lewis was writing regularly for the Daily Worker, New Masses, and rose in prominence. Arrested for ‘vagrancy’, Lewis was sentenced to 112 days on a chain gang, and given he was a Black Communist union organizer, a possible death sentence in jail. Released after and International Labor Defense campaign, comrade Lewis left for the Soviet Union in 1931. Diagnosed with T.B. he was sent to Yalta in the Crimea for medical care. There he died on June 1, 1931 at 27 years old. Gilbert Lewis, a Black, working class Communist from New Orleans, share-cropper and labor organizer lies buried in Yalta today.

‘In Action Against Jim-Crow’ by Gilbert Lewis from Labor Defender. Vol. 5 No. 2. February, 1930.

That white workers of America are firmly determined to cast off the imperialist ideology of race prejudice and join hands with their darker brothers in a struggle against their common enemy, the capitalist oppressor, was brought out fully at the Fourth National Convention of the International Labor Defense held in Pittsburgh, December 29, 30, 31, 1929. This fact was demonstrated from time to time as speaker after speaker, from all parts of the country—as far West as Seattle, as far South as Atlanta—took the floor and voiced his or her determination of fighting side by side with the Negro workers in their struggle against jim-crowism, segregation, lynching, etc.—to support their demands for full economic, political and social equality and to strive together for the complete emancipation of the working class.

To say that this convention made labor history is not enough; to say that it struck a new note in race relations is to confuse the issue; and even to say merely that the “convention was united in supporting the demands of Negro equality,” as was stated by the capitalist press, is to minimize the facts. In order that justice may be done to what occurred at this convention it must be clearly and emphatically stated that here was sounded a note of solidarity never before attained at any convention in the history of organized labor in the United States!

Visitors and delegates attending for the first time a convention of an organization based upon the principles of the class struggle, were completely overwhelmed, astounded—found themselves entirely at a loss to give expression to what was taking place. So great, indeed, was the wave of class unity that even old-timers were carried away, swept off their feet. It would seem that these workers, many of them from the bourbon South, hotbed of race prejudice, land of the jim-crow and mob rule, after years of wandering in a jungle of exploitation and oppression had at last discovered the path that would lead to their eventual emancipation.

But the convention was not only one of words but of action as well. The great demonstration at the Monongahela House Hotel will long be remembered as one of the sharpest expressions of solidarity ever witnessed in Pittsburgh, or any other town. Of this demonstration even the capitalist press whose business it is to conceal expression of solidarity from the workers, was forced to declare: “The demonstration was one of the most unusual ever staged here.”

And what of the Negro workers: What was their reaction to this expression of solidarity? They were there, some thirty of them. They had come from all parts of the country: North, East, South, West They had come with the express purpose of voicing their willingness, nay, their eagerness, to fight side by side, to the very death, with their white brothers for emancipation. And this is what they did. They took the floor, one after the other, and in fiery passionate words made it known far and wide that they had no illusions as to the source from which their oppression came. They made it clear that the propaganda of the capitalist that the “poor white” was the Negro’s natural enemy would fall on deaf ears. They knew that their emancipation lies in linking themselves with their fellow white workers for a complete overthrow of the capitalist system. They said as much.

They were connected with no political party, most of them. Just workers from the shops and factories. But they understood the class struggle. It was significant that none of them interpreted the action of the white delegates in fighting the hotel as a favor being bestowed upon the Negroes. They understood it for exactly what it was—part and parcel of the class Struggle, an act of solidarity.

It is also encouraging to see that they are rapidly getting over their illusion about the various political parties. It is no good telling these workers that Lincoln freed them and that the Republican party is therefore their party. They know that they are in a state of wage slavery today almost equivalent to chattel slavery. They know that the Republican party is a jim-crow party, the party which shoots down workers in Haiti and Nicaragua. Don’t mention the Democratic party to them. They know that it is the party that exploits, oppresses and even lynches Negroes in the South. Neither have they any concern with the yellow, equally jim-crow Socialist party.

But when you mention the Communist Party, then it is a different story. They know it is the only party capable of leading the struggles of the workers and driving them to complete emancipation from the toils of the imperialist oppressors. They know that only the program put forth by the Communist Party will succeed in smashing race prejudice.

When you balance the International Labor Defense against the social-fascist Negro nationalist organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Universal Negro Improvement Association of Marcus Garvey, they at once tell you that the I.L.D. is the organization for them. They know that these Negro nationalist organizations will not and cannot make a fight for liberation. The Negroes went from this convention staunch defenders of the I.L.D., the champion of the oppressed Negro masses.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Not only were these among the most successful campaigns by Communists, they were among the most important of the period and the urgency and activity is duly reflected in its pages. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of original issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1930/v05n02-feb-1930-ORIG-LD.pdf