Nearing looks at the unions of teachers and school workers.

‘X. The Organization of Educational Workers’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

X. THE ORGANIZATION OF EDUCATIONAL WORKERS.

Experiments with student organization probably constitutes one of the most important contributions of the Soviet educational system. Of almost equal interest are the experiments that are now being made with the organization of education workers in the Soviet Union.

Educational workers, like all other workers in the Soviet Union are organized into trade unions. Unlike the teachers’ trade unions elsewhere, however, these unions include all workers in educational institutions. This is the principle of industrial unionism applied to the educational field.

Older trade unions were organized by crafts: carpenters in one union, bricklayers in a second and stone-masons in a third. This form of organization exists in most of the great industrial centres of the world at the present time, and it was the logical product of a stage in the development in industrial society when each craft was organized by itself. Business consolidations have replaced the old craft organization of industry. Since the Russian unions were all organized in the period since 1905, they never went through the stage of craft organization, but started on an industrial basis when the Revolution cleared the ground for them in 1917. There were 23 unions organized in all, and one of them was the union of education workers.

According to the industrial principle, an entire plant or productive unit must be organized together. If it is producing coal, all of the workers in and about the plant belong to the miners’ organization. If it is a steel plant, all of the workers belong to the metallists. That same principle has been applied to education, and with a few minor exceptions, all workers in educational institutions belong to the Education Workers’ Union.

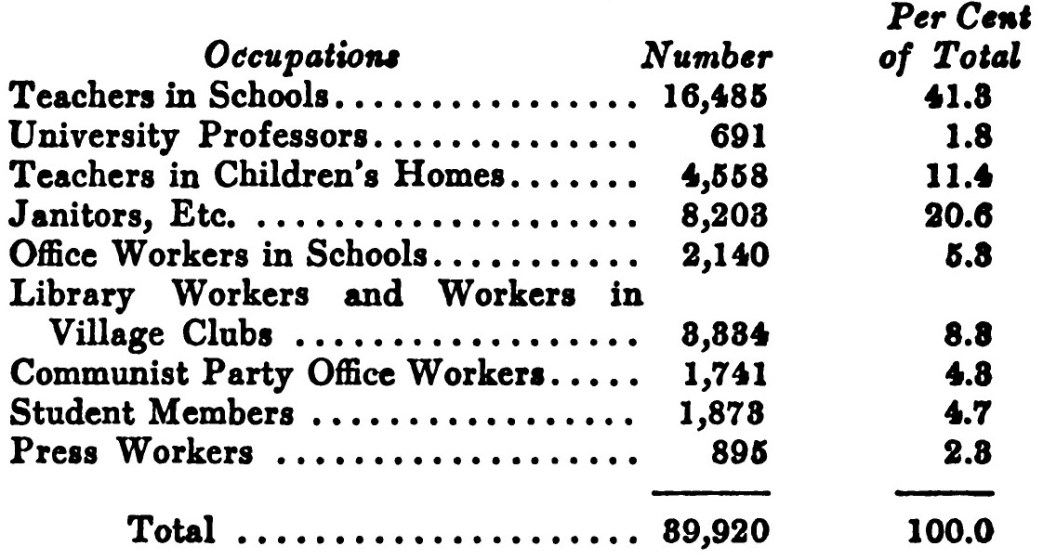

Here are the figures showing the composition of a typical section of the Education Workers’ Union. They cover the North Caucasus Region, and are for September, 1925. In this entire region all but about 1.5 per cent of the education workers were in the union. Most of the non-unionized element was in the villages:

Only a little more than half of the North Caucasus Education Workers were teachers. The remainder of the union members were occupied in and about educational institutions, but not in a teaching capacity. All of the members of the union were a part of the personnel of the educational system.

Soviet education workers were variously organized. In the Ukraine, for example, where there were 101,363 members in the union on January 1, 1925, there were four series of organizations: the smallest was the village; the next was the raion, which corresponds roughly to an American township; the third division was the okrug, which resembles an American county, and the final organization was that of the Ukrainian Republic. The same type of organization existed all over the Soviet Union.

Where there were less than ten education workers in a village, they were expected to elect a secretary. Where there were more than ten, they elected a committee of three. The secretaries of the smaller groups and the committees of the larger groups were responsible for the establishment and maintenance of culture centres in their local communities.

Each village group elected delegates who formed the members of the raion group. The raion groups elected delegates who formed the members of the okrug group. The okrug groups elected delegates who formed the Education Workers’ Congress of the Ukrainian Republic. This congress, meeting once a year, elected delegates to the Education Workers’ Congress of the Soviet Union. Practically the organization was strong in the larger centres, and was weak in the villages, unless there happened to be one or more strong teachers in charge of the local schools. Theoretically the organization was very complete.

Officers of the Ukrainian Education Workers’ Union had some interesting figures regarding their 101,363 members. Of this total, 60.6 per cent were teachers in the elementary schools; 8.6 per cent were teachers in professional schools; 5.1 per cent were teachers of political education. Technical workers in the schools–janitors, clerks, etc., made up 18.3 per cent of the entire union membership.

For the Soviet Union the number of educational workers who were in the union on April 1, 1925 was 583,811. On the same date in 1923 the union had 383,645 members, and in 1924, 516,818 members. About four-fifths of these members were men. Elementary teachers were 45 per cent of the total membership for the Soviet Union. Teachers in professional schools were 2.8 per cent; in higher technical schools and universities, 4.8 per cent; and in pre-school classes, schools for backward children and other educational institutions, 6.1 per cent. Administrative and technical workers in the schools were 23.4 per cent of the total.

The Education Workers’ Union had two main functions: to protect its members through their collective agreements, and to raise their professional and cultural standards; (2) to raise the cultural level of their communities by raising standards of education and improving social organization.

The union signed a collective agreement with whatever department paid the salaries of the educational workers. The workers in an institution under the control of the local educational authorities in Baku signed an agreement with these local authorities. Workers in national museums signed an agreement with the department of the Soviet Union Government that handled museums. In all of these agreements provisions were made for the wages, the conditions of employment and the handling of grievances. All such collective agreements made locally were subject to review by the central committee of the Soviet Educational Workers’ Union. While they were not uniform in detail, they followed out the same general principles.

Education workers maintained a club in each of the chief centres. These clubs, like the clubs maintained by the other labor unions, housed the cultural work and the social activities of the union. The building occupied by the Education Workers’ Club at Kharkov was formerly the house of one of the rich merchants of the city. During the Revolution this house was taken over by the city, and in July, 1925, it was placed at the disposal of the union. The union spent about ten thousand rubles in repairing and refitting the house, for which they do not pay any rent. It was fully equipped for club purposes when I visited the city.

The club was in charge of a committee of the local union. This committee selected a manager who spent all of his time at the club and was paid for his work. In the main lecture hall, which seated perhaps three hundred, there was a lecture every evening except Saturday, which was reserved for social events. The night that I visited the club a professor from the University was delivering a lecture in a course on pedagogy. Various subjects were handled on different nights. An attempt was made, in planning the program, to keep all of the work definitely educational.

In another room there was a special library for the janitors and care-takers of the schools. A committee of technical workers was meeting in this room. The main library of the club, devoted largely to education, contained 11,000 volumes. There was a reading room in connection with this library where the leading educational papers were on file. The Young Communist Group of the Educational Workers’ Union was meeting in another room. Still other rooms were occupied by class and committee meetings. There was a dining room and a large social room.

At the Rostov education workers’ club they varied this program by having one evening a month devoted to “question and answer.” On this evening the members of the union executive committee all sat on the platform, and the members of the union held the floor and asked questions. It was generally the liveliest meeting of the month.

In all of the clubs that I visited there were excellent wall newspapers, written (or typed) for the most part by the younger members of the organization. It is worth while noting that a great deal of the educational work of the Soviet Union was being carried on by people under 25, and much of it by people under 20.

The Rostov Club had 2,015 members. The dues were less than 25 cents per month, varying with the salary.

Such plants were very expensive to keep up. Their existence was made possible by the “culture funds” that were at the disposal of the unions. In the North Caucasus, the collective agreement required the school authorities to pay into the union treasury, for cultural purposes, one per cent of the amount of the total salary budget. The union was of course bound to use these funds for culture work.

The Education Workers’ Union did not control the appointment of teachers nor did it determine the course of study, but it generally had its representatives on the committees that were carrying on this work. In this respect, the education workers are in the same position as the other workers in the Soviet Union. Nowhere do they control production. But everywhere they have a voice in determining the conditions under which the workers carry on productive activity, and everywhere they have a veto over the hiring and the discharge of workers.

In the case of the education workers, as elsewhere, the practical method of protecting themselves was the insertion in the collective agreement of a clause providing that in the filling of positions the school authorities should give union teachers the preference over non-union teachers. So long as the union can provide competent union members, it can virtually control the labor market.

In the smaller communities the teachers were expected to be the leaders of local cultural and social activity. They were to occupy the position of “the central public figure in the village” and were to become “the close advisers and helpers of the peasants.” When this result has been achieved, science and the school will dominate village life. “This will not merely be the victory of the teachers over the priests, but the victory of the Communists over the stagnation, backwardness and prejudices of the village.” This means that the teacher will be the cultural leader of the rural masses.

Soviet educational organization and Soviet pedagogy all are aimed in this direction. Practically, the teachers are expected to carry out the plan by taking an active part in the organization of village-houses, reading-rooms, libraries, entertainments, lecture courses, and the like. The rural teacher thus becomes far more than an instructor of children. He is a general adviser and organizer of the social and cultural side of village life.

Through such methods the Soviet authorities expect to break down the wall of backwardness that surrounds the village. The older generation is being taught to read and write. The younger folks are being taught, in the schools and in the community, to organize life on a new basis. As these plans mature, the Education Workers’ Union will play a larger and larger part in the rural cultural life of the Soviet Union.

As yet it is too early to judge what effect this widespread organization of the education workers will have upon the education workers themselves. There is no country in the world where teachers, for example, are as completely organized as they are in the Soviet Union. As students in the normal schools and teachers’ colleges they are student members of the union. They secure their positions in educational institutions because of their union membership. All of them are united, locally and nationally, and they are expected, as members of the union, to work out certain very important cultural activities in the communities where they teach.

Furthermore, as in no other country in the world, the workers in educational fields other than the schools, are brought together in the same organization. Press workers, workers in libraries and museums, and workers in technical research are all members of the same educational body. They meet and function together as a part of the educational machine.

Again, through the industrial union principle, all of the workers in educational institutions, whether they teach or wash floors, are a part of the same general occupational field, and therefore belong in the same union. This establishes a sense of solidarity in the ranks of all those who are connected with educational work, no matter what may be the capacity in which they function.

Years must pass before it is apparent just what effects such drastic departures from the academic tradition of “professional standing” will have upon the tone of the work done by Soviet educators. Certainly, if there is anything in the principle of organization, it will have a rare opportunity to show itself among the education workers of the Soviet Union. They are thoroughly organized themselves, and they are an organic part of the society in which they are carrying on their activity.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf