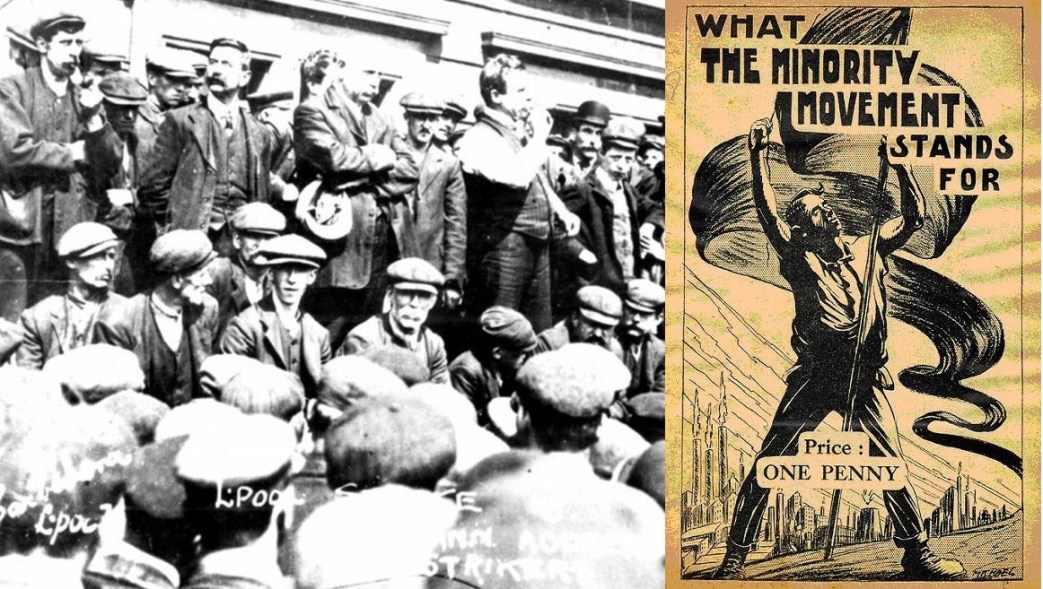

Tom Mann on the background to Britain’s version of the T.U.E.L., the National Minority Movement affiliated to the Red International of Labor Unions.

‘Roots of the British Minority Movement’ by Tom Mann from Workers Monthly. Vol. 4 No. 2. December, 1924.

THE minority movement in Great Britain is not so new as many seem to think. Special activity has been shown recently, and considerable changes are taking place in the trade union movement as a result of these activities of the revolutionary minorities. The beginning is to be found, however, many years in the past.

In the year 1910, fourteen years ago, the present writer, then as now a member of the Amalgamated Engineers, was identified with kindred spirits who associated together to form an Industrial Syndicalist League. This was done because the trade union movement was badly organized numerically and objectively, and increasing reliance was being placed upon parliamentary action. The League issued a monthly pamphlet—“The Industrial Syndicalist,” the first of which appeared in July, 1910.

I have said reliance was placed on parliament; it is necessary to say also that among the more militant of the workers increasing dissatisfaction with the results of parliamentary effort was expressed, as no rise in the standard of life took place and the associations in connection with the parliamentary institutions had a detrimental effect on the characters of the workmen members returned to parliament. In short, neither by political nor by industrial action was any real militancy shown. The term syndicalist was used to popularize the industrial movement on the lines As the French at that time were attaching less importance to legislation and increasing importance to industrial organization, so in England there were those who felt the necessity for similar action.

We were not anti-Parliament, but indifferent to it, holding that the first essential was a revolutionary objective, and solidarity on the industrial field to achieve this. We were entirely opposed to the starting of new unions, contending that rank and file activity of the right kind and right amount would make the unions what they ought to be. In setting forth the aims of the I.S.L. (Industrial Syndicalist League) we put the matter thus in the first number of the magazine:

“But what will have to be the essential condition for the success of such a movement? That it will be avowedly and clearly revolutionary in aim and method. Revolutionary in aim, because it will be out for the abolition of the wages system and for securing to the workers the full fruits of their labor, thereby seeking to change the system of society from capitalist to socialist. Revolutionary in method, because it will refuse to enter into any long agreements with the masters, whether with legal or state backing, or merely voluntarily; and because it will seize every chance of fighting for the general betterment—gaining ground and never losing any. Does this mean that we should become anti-political? Certainly not. Let the politicians do as much as they can, and the chances are that once there is an economic fighting force in the country, ready to back them up by action, they will actually be able to do what now would be hopeless for them to attempt to do…Those who are asleep had better wake up or they’ll be kicked out of the way. Those who say it can’t be done are hereby invited to stand out of the way and look on while it is being done.”

A vigorous campaign was carried on thruout the country and on November 26 of that same year was held the First Conference on Industrial Syndicalism. This conference was held in the Coal Exchange, Manchester, and was attended by 198 delegates. The conference was presided over by Albert A. Purcell of the Furnishing Trades, the same Mr. Purcell who presided over the recent Trades Union Congress at Hull, and who is chairman of the General Council of the Trade Union Congress and member of Parliament for Coventry. One of the resolutions carried at that conference will show the motive; it was as follows:

“That, whereas the sectionalism that characterizes the trade union movement of today is utterly incapable of effectively fighting the capitalist class and securing the economic freedom of the workers, this conference declares that the time is now ripe for the industrial organization of all workers on the basis of class—not trade or craft—and that we hereby agree to propagate the principles of syndicalism thruout the British Isles, with a view to merging all existing unions into one compact organization for each industry, all laborers of every industry in the same organization as the skilled workers.”

Such was the effect of this movement that early in the following year a general restlessness began to manifest itself among many sections of workers. Special attention was given to transport workers, and in June, 1911, began the great strike of sailors and firemen at all British ports, and which soon included all other sections of workers connected with water transportation: dockers, lightermen, carters, warehouse workers, and ultimately the railwaymen. Considerable demands were made and obtained, an enormous impetus was given to industrial organization, a million members were added to the trade union movement, and sectionalism was effectively checked, though certainly not destroyed. But in connection with railway employees, the three unions, known as the Amalgamated Society of Railway Men, the General Railway Workers Union, and the Signalmen and Pointsmen, dropped their individual existence and merged into one organization, since that time known as the N.U.R., or National Union of Railwaymen.

In the period that has elapsed since the special activities described, there has been the world war and its tragedies and lessons. In Great Britain we still have eleven hundred trade unions, and those of us who have been identified with the Red International of Labor Unions have in season and out kept up the agitation for amalgamation, for one hundred per cent organization in the unions, and for industrial solidarity over the whole industrial field.

Owing to the fact that many syndicalists of the continent hesitated and, in some cases, refused to make common cause with the Red International, we in Britain ceased to use the term syndicalist to describe ourselves. The achievements of the Russian revolution, the establishment of the Soviets, the formation of the Red International, were in our judgment all vitally essential to insure the success of the world revolution. Becoming identified with the R.I.L.U. and keeping up a propagandist campaign among the unions and trade councils we aimed at encouraging the men in any locality to take the initiative and to formulate plans of campaign. With the South Wales Miners who had passed through various phases of agitation and organization, the term that they made most frequent use of to describe themselves was the Minority Movement. In the space of a year this term became general in the coal fields, and increasingly so in other industrial districts.

So it came about when we were organizing a National Congress the greater part of our members and sympathizers were already known as connected with the Revolutionary Minority Movement. So this is now the accepted term and there is a big program of work to be achieved. This Conference has already been reported. (See The Labor Herald, October, 1924.) Included in the work of the Minority Movement are systematic visits to trade union branches to give brief explanatory addresses, to take an active part in the work of the unions, to act as delegate from the union branch to the Trades Council, to vigorously urge on and to actually help in bringing about amalgamation of unions in the same industry, to advocate and demonstrate the necessity for international organization, to explain the class struggle and the international aspect of it, to expose the Second International of reformists and to work assiduously for a united front on the basis of the class war.

Already there is evidence of the good effect of the work done. The Trade Union Congress held one month ago at Hull came substantially nearer to us than any previous Congress ever has. It was a great thing that a resolution was carried authorizing action to be taken by the General Council to take all necessary steps to reorganize the machinery of trade unionism on the basis of real industrial unionism. Already definite action has commenced in this regard. We of the Minority Movement have been very persistent in demanding that powers should be given to the General Council to take action in the name of the whole movement and arrange for national solidarity in the event of big struggles.

Given good tactics there are great opportunities for the Minority Movement to stimulate, and to educate on class conscious lines the great and (again) growing trade union movement. The reception that was given to Comrade Tomski at the Hull Congress, when our Russian comrade rose to give his speech, was very significant. It was by far the most enthusiastic five minutes of the Congress, and now seven have been appointed by the General Council to visit Russia, having accepted the invitation of the Russian Trade Unions. We are traveling fairly rapidly towards the great goal.

The Workers Monthly began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Party publication. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and the Communist Party began publishing The Communist as its theoretical magazine. Editors included Earl Browder and Max Bedacht as the magazine continued the Liberator’s use of graphics and art.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/wm/1924/v4n02-dec-1924.pdf