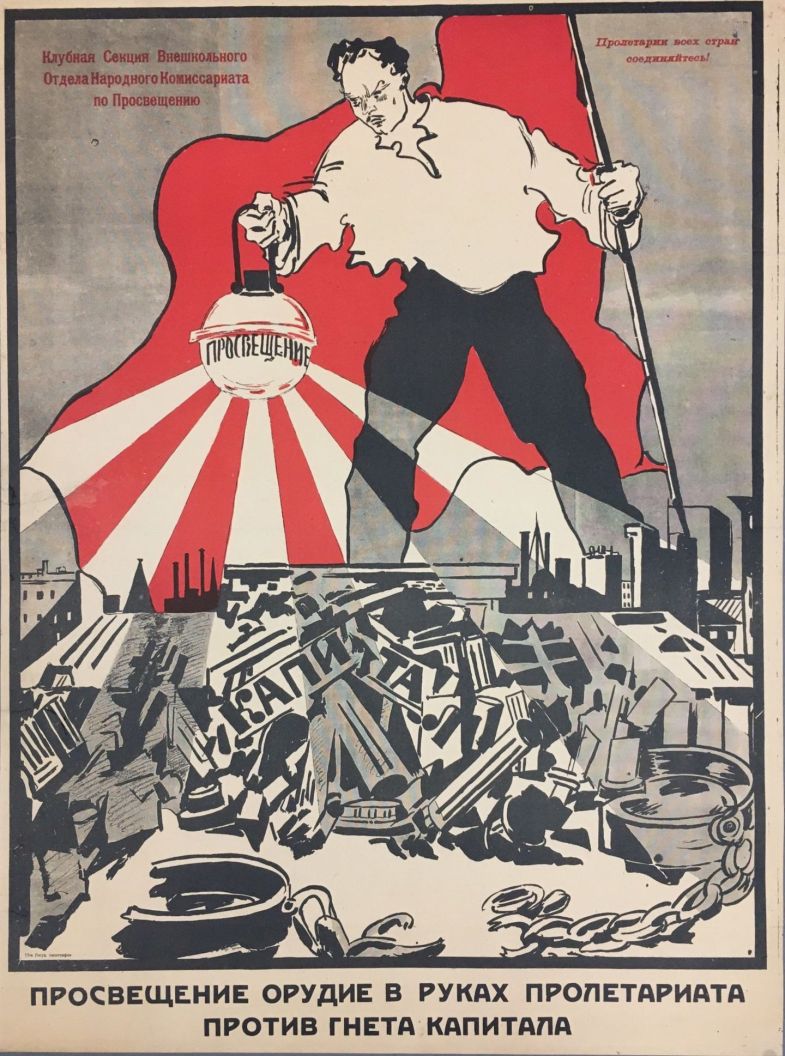

Before the revolution, higher education for Russian workers was unthinkable.

‘XI. Higher Education for Workers’ by Scott Nearing from Education in Soviet Russia. International Publishers, New York. 1926.

XI. HIGHER EDUCATION FOR WORKERS.

Education in western Europe existed, in the early days, for the priests, and for some of the retainers of the nobility. The merchant class received a little school training. Later the sons, and finally the daughters of the upper classes were given educational advantages, but it was not until the opening years of the nineteenth century that education was offered to the masses of the people. Even then they did not receive much education–reading, writing and a little arithmetic and distorted history.

Mass education was provided for two main reasons: first because the introduction of machine production had created a demand for skilled workers that the industries themselves could not meet; second because the workers, as they began to formulate their demands for emancipation, discovered that one of the first requisites for the success of their movement was education. All through the last century, therefore, the trade unions of industrial countries were pressing the demand that more effective educational opportunities should be open to the children of the workers.

In some countries, that were less developed industrially–Russia, for example this education was given grudgingly. Even where the sons and daughters of the workers were permitted to enter the higher schools, they were admitted in such tiny proportions, as compared with the great masses excluded, that for all practical purposes, the masses were excluded.

In other countries the exclusion took a less offensive and a far more practical form. The costs of higher education were heavy. In England, for example, a worker, if he put his whole yearly surplus into the project could not send a son through the higher schools. Gentlemen, who had more money, could send their sons without any trouble. The consequence was that, even up to the present time, the majority of those who go to the English Universities were the sons of the landed aristocracy, the successful merchants and bankers and the more fortunate professional people. This process of selection for the student body of the higher schools was carried on without any great reference to merit. A worker’s son went into the factory because he was the son of a worker, while an earl’s son or a banker’s son went to the university because of the social and economic position occupied by his parents.

Again a practical consideration arose. There were poor boys, bright poor boys,–the sons of clergymen and teachers, who showed great promise. They were given scholarships because the members of the ruling class realized that they needed additional brains to direct public affairs. Occasionally there was some workingman’s son who, by sheer grit and energy and ability, scaled the wall of higher education. Of course such cases were rare, but they showed that there were workingmen’s sons with brains.

By the time higher education was well organized in the United States (late in the last century) this was taken for granted, and the technical schools offered free scholarships and fellowships for the abler among the poor students. This did not equalize the disproportion between the son of a rich man and the son of a worker. worker’s son went to college because he had energy and ability. The rich man’s son went to college because his father had money. Colleges were still filled with the children of the well-to-do, but there was sufficient leeway so that the brainy poor boy or girl could get a higher education.

The circumstances under which this higher education was secured surrounded by the children of the rich, and dominated by their ideals and standards–made it almost inevitable that the children of the poor, if they did get through the higher schools, would come out steeped in the ideology of the ruling classes.

The higher schools were therefore an effective means of persuading the abler among the children of the workers that their wisest move was to become members of the ruling classes, or at least to act as assistants and employes of the ruling class. The higher schools remained under the control of the ruling class, whose members sat upon the boards and committees of the colleges and universities, directed their policy with scrupulous care, and watched over the members of the teaching force, picking them with an eye to their usefulness. Occasionally, despite this care, some liberal or radical slipped in among the members of the teaching body. Where he could be disposed of by promotion and a higher salary, he was handled in that way. Otherwise, if he persisted in his heresies, he was dismissed on one pretext or another.

There were universities in Europe that became the centres of revolutionary activity. For the most part, however, the higher schools were safely conservative, and were wholly in the hands of the established order.

When the Revolution occurred in Russia the universities were generally conservative. There were radical professors here and there, and many radicals among the students, but the bulk of the teachers were safe and sane. In a very real sense, therefore, after the Revolution occurred, the higher schools were still the seat of reaction and of counter-revolution. As lately as 1925 I visited one of the older higher technical schools in which there was not a single Communist on the faculty outside of the departments of social science.

One higher technical school, devoted to agriculture and engineering, had a student body in 1910-11 made up as follows: sons of military and industrial leaders, one-fifth; sons of nobility, one-fifth; sons of the trades-people, one-fifth; sons of ministers, one-fifth; sons of peasants, one-fifth. There were practically no children of the wage- earners in the institution. I secured these figures from a man who had been on the faculty for many years, and who was not a Communist. At the present time the stdent body of this institution is made up almost entirely of the sons and daughters of peasants and workers.

The higher technical school at Stalinov reports that 95 per cent of its student body consists of the children of wage-earners and peasants. Other higher schools report a similar proportion.

Within a few years the higher schools of the Soviet Union have been transformed from centres of capitalist culture into centres of working-class culture, in so far as the make up of the student body is concerned. The teaching body is still largely non-working class in its origin.

Soviet higher education is to-day for the children of peasants and workers just what capitalist higher education, in most capitalist countries, is for the children of manufacturers and bankers. (I talked with one school principal in Germany who told me that in 1925, a child required about 150 marks per year minimum, beside his clothes and keep, to go through a middle school (high school), and about 600 marks per year, minimum, to go through a university. At that time skilled workers in Germany were receiving from 30 marks per week and up, and requiring practically all of it to buy the barest necessaries for the family).

How have the Soviet educators brought about this result? By two simple methods: (1) Where there is a choice between the child of a worker or peasant and the child of a profiteer, the former always has the decision. Places in the Soviet higher schools have been too few to meet the demand. Workers’ children have gone in and the children of business and professional people have stayed out. (2) By making it economically hard for the children of profiteers to go to higher schools, and economically easy for the children of workers and peasants to go to higher schools.

Even in the lower schools, the children of the well-to-do must pay. The children of the workers go to the lower schools free. But in the higher schools, the children of the well-to-do must pay, while the children of workers and peasants get their tuition, board and rooms free, and in many cases have a small monthly stipend beside.

At the inception of this policy, the labor unions gave a great deal of support for workers and for the children of workers, in order that they might get to school. The rabfacs were handled for a time largely on this basis. But at present the policy has been adopted by the governmental authorities and they provide a large share of the support.

Students who are children of the workers and peasants do not receive much for going to the higher schools, but with their tuition and living supplied, their stipend is sufficient to enable them to get through school without calling on their parents for assistance. This is the intent of the policy.

Theoretically the basis of these stipends is the merit of the recipient. He is selected by his union, or by the village Soviet, or by some other labor group, as a promising man; or else he enters school in competition with other aspirants for the educational opportunity. There will be many mistakes made, in this process, and favoritism will be shown, but with the authorities that do the selecting so numerous and so local that they know each applicant personally, there is little chance for the development of a selecting bureaucracy, and there seems to be every likelihood that able students will have a better chance to obtain an education in the Soviet Union than in any other large country of the world. Certainly a student who shows ability under the Soviet system can hardly fail to obtain as much education as he can absorb. Incidentally, that education is developed, under the Soviet system, as thoroughly in the field of music and art as it is in the field of science.

Foreword, I A Dark Educational Past, II The Soviet Educational Structure, III Pre-School Educational Work, IV Social Education—The Labor School, V Professional Schools (High Schools), VI Higher Educational Institutions, a. Higher Technical Schools (Colleges), b. Universities, c. Institutes, VII Experiments With Subject-Matter—The Course of Study, VIII Experiments With Methods of Instruction, IX Organization Among the Pupils, X The Organization of Educational Workers, XI Higher Education For Workers, XII Unifying Education, XIII Socializing Culture.

International Publishers was formed in 1923 for the purpose of translating and disseminating international Marxist texts and headed by Alexander Trachtenberg. It quickly outgrew that mission to be the main book publisher, while Workers Library continued to be the pamphlet publisher of the Communist Party.

PDF of later edition of book: https://archive.org/download/in.ernet.dli.2015.123754/2015.123754.Education-In-Soviet-Russia.pdf