Lenin finds a gold mine in a new collection of letters of Marx, Engels, and others to Friedrich Sorge, their comrade in New Jersey. Lenin follows and comments on the correspondence, relating it to Russia’s then reality, covering the labor movement in the U.S. and Europe, as well as Marx and Engels’ fight against opportunists in the German party.

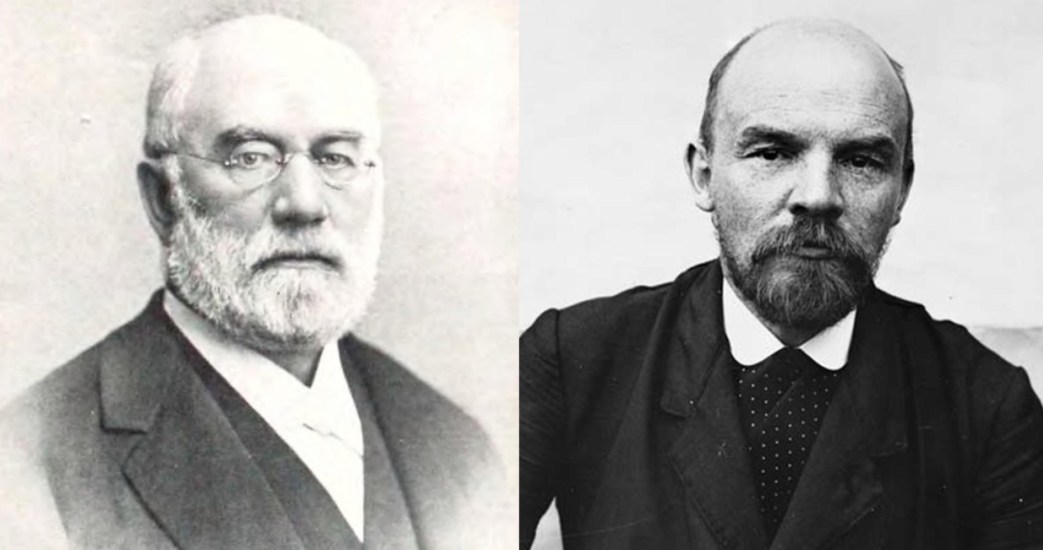

‘Preface: Letters to Friedrich Sorge’ (1907) by V.I. Lenin from Selected Workers, Vol. 11. International Publishers, New York. 1929.

THE collection of letters by Marx, Engels, Dietzgen, Becker and other leaders of the international labour movement of the past century here presented to the Russian public is a needed addition to our advanced Marxist literature.

We will not dwell in detail here on the importance of these letters for the history of Socialism and for a comprehensive treatment of the activities of Marx and Engels. This aspect of the matter requires no explanation. We shall only note that an understanding of the published letters necessitates an acquaintance with the principal works on the history of the International (see Jaeckh, The International, Russian translation in the Znaniye edition), on the history of the German and American labour movements (see Fr. Mehring, History of German Social-Democracy, and Morris Hillquit, History of Socialism in America), etc.

Neither do we intend here to attempt a general outline of the contents of this correspondence or to express an opinion about the importance of the various historical periods to which it relates. Mehring has done this extremely well in his article, Der Sorgesche Briefwechsel (Neue Zeit, 25, Jahrg., No. 1 und 2),1 which will probably be appended by the publisher to the present translation or will be issued as a separate Russian publication.

The lessons which the militant proletariat must draw from an acquaintance with the intimate sides of Marx’s and Engels’ activities over the course of nearly thirty years (1867-1895) are of particular interest to Russian Socialists in the present revolutionary period. It is, therefore, not surprising that the first attempts made in our Social-Democratic literature to acquaint the readers with Marx’s and Engels’ letters to Sorge were also linked up with the “burning” issues of Social-Democratic tactics in the Russian revolution (Plekhanov’s Sevremennaya Zhizn and the Menshevik Otkliki). And it is to an appreciation of those passages in the published correspondence which are specially important from the point of view of the present tasks of the workers’ party in Russia that we intend to draw the attention of our readers.

Marx and Engels deal most frequently in their letters with the burning questions of the British, American and German labour movements. This is natural, because they were Germans who at that time lived in England and corresponded with their American comrade. Marx expressed himself much more frequently and in much greater detail on the French labour movement, end particularly on the Paris Commune, in the letters he wrote to the German Social-Democrat, Kugelmann.2

It is highly instructive to compare what Marx and Engels said of the British, American and German labour movements. The comparison acquires all the greater importance when we remember that Germany on the one hand, and England and. America on the other, represent different stages of capitalist development and different forms of domination of the bourgeoisie as a class over the entire political life of these countries. From the scientific standpoint, what we observe here is a sample of materialist dialectics, of the ability to bring out and stress the various points and various sides of the question in accordance with the specific peculiarities of varying political and economic conditions. From the standpoint of the practical policy and tactics of the workers’ party, what we see here is a sample of the way in which the creators of the Communist Manifesto defined the tasks of the fighting proletariat in accordance with the varying stages of the national labour movement in various countries.

What Marx and Engels most of all criticise in British and American Socialism is its isolation from the labour movement. The burden of all their numerous comments on the Social-Democratic Federation in England and on the American Socialists is the accusation that they have reduced Marxism to a dogma, to a “rigid (starre) orthodoxy,” that they consider it “a credo and not a guide to action,”3 that they are incapable of adapting themselves to the labour movement marching side by side with them, which, although helpless theoretically, is a living and powerful mass movement.

“Had we from 1864 to 1873 insisted on working together only with those who openly adopted our platform,” Engels exclaims in his letter of January 27, 1887, “where should we be to-day?”4

And in an earlier letter (December 28, 1886), in reference to the influence of the ideas of Henry George on the American working class, he writes:

“A million or two of workingmen’s votes next November for a bone fide workingmen’s party is worth infinitely more at present than a hundred thousand votes for a doctrinally perfect platform.”5

These are very interesting passages. There are Social-Democrats in our country who hastened to make use of them in defence of the idea of a “labour congress” or something in the nature of Larin’s “broad labour party.” Why not in defence of a “Left bloc” we would ask these precipitate “utilisers” of Engels. The letters from which the quotations are taken relate to a time when the American workers voted at the elections for Henry George. Mrs. Wischnewetzky—an American woman who married a Russian and who translated Engels’ works—asked him, as may be seen from Engels’ reply, to make a thorough criticism of Henry George. Engels writes (December 28, 1886) that the time has not yet come for that, for it is necessary that the workers’ party begin to organise itself, even if on a not entirely pure programme. Later on the workers would themselves come to understand what is amiss, “would learn from their own mistakes,” but “anything that might delay or prevent that national consolidation of the workingmen’s party—no matter what platform—I should consider a great mistake…”6

Engels, of course, perfectly understood and frequently pointed out the utter absurdity and reactionary character of the ideas of Henry George from the Socialist standpoint. In the Sorge correspondence there is a most interesting letter from Karl Marx dated June 30, 1881, in which he characterises Henry George as an ideologist of the radical bourgeoisie. “Theoretically, the man [Henry George] is utterly backward (total arriére),” wrote Marx. Yet Engels was not afraid to join with this Socialist reactionary in the elections, provided there were people who could warn the masses of “the consequences of their own mistakes” (Engels, in the letter dated November 29, 1886).

Regarding the Knights of Labour, an organisation of American workers existing at that time, Engels wrote in the same letter:

“The weakest [literally: rottenest, faulste] side of the K. of L. was their political neutrality…The first great step of importance for every country newly entering into the movement is always the organisation of the workers as an independent political party, no matter how, so long as it is a distinct workers’ party.”7

It is obvious that absolutely nothing in defence of a leap from Social-Democracy to a non-party labour congress, etc., can be deduced from this. But whoever wants to escape Engels’ accusation of degrading Marxism to a “dogma,” “orthodoxy,” “sectarianism.” etc., must conclude from this that a joint election campaign with radical “social-reactionaries” is sometimes permissible.

But what is more interesting, of course, is to dwell not so much on these American-Russian parallels (we had to refer to them so as to answer our opponents), as on the fundamental features of the British and American labour movement. These features are: the absence of any at all big, nation-wide, democratic problems facing the proletariat; the complete subjection of the proletariat to bourgeois politics; the sectarian isolation of groups, handfuls of Socialists from the proletariat; not the slightest success of the Socialists at the elections among the working masses, etc. Whoever forgets these fundamental conditions and sets out to draw broad conclusions from “American-Russian parallels,” displays extreme superficiality.

Engels lays so much stress on the economic organisations of the workers in such conditions because he is dealing with the most firmly established democratic systems, which confront the proletariat with purely Socialist tasks.

Engels stresses the importance of an independent workers’ party, even though with a bad programme, because he is dealing with countries where hitherto there had not been even a hint of political independence of the workers, where, in politics, the workers most of all dragged, and still drag, after the bourgeoisie.

It would be ridiculing Marx’s historical method to attempt to apply the conclusions drawn from such arguments to countries or historical situations where the proletariat had formed its party before the bourgeois liberals had formed theirs, where the tradition of voting for bourgeois politicians is absolutely unknown to the proletariat, and where the next immediate tasks are not Socialist but bourgeois-democratic.

Our idea will become even clearer to the reader if we compare the opinions of Engels on the British and American movements with his opinions on the German movement.

Such opinions, and extremely interesting ones at that, also abound in the published correspondence. And what runs like a red thread through all these opinions is something quite different, namely, a warning against the “Right wing” of the workers’ party, a merciless (sometimes—as with Marx in 1877-79—a furious) war upon opportunism in Social-Democracy.

Let us first corroborate this by quotations from the letters, and then proceed to a judgment of this phenomenon.

First of all, we must here note the opinions expressed by Marx on Hochberg and Co. Fr. Mehring, in his article Der Sorgesche Briefwechsel, attempts to tone down Marx’s attacks, as well as Engels’ later attacks on the opportunists—and, in our opinion, rather overdoes the attempt. As regards Hochberg and Co. in particular, Mehring insists on his view that Marx’s judgment of Lassalle and the Lassalleans was incorrect. But, we repeat, what interests us here is not an historical judgment of whether Marx’s attacks on particular Socialists were correct or exaggerated, but Marx’s judgment in principle on definite currents in Socialism in general.

While complaining about the compromises of the German Social-Democrats with the Lassalleans and with Duhring (letter of October 19, 1877), Marx also condemns the compromise “with the whole gang of half-mature students and super-wise doctors” (“doctor” in German is a scientific degree corresponding to our “candidate” or “university graduate, class I”), who want to give Socialism a “higher idealistic” orientation, that is to say, to replace its materialistic basis (which demands serious objective study from anyone who tries to use it) by modern mythology, with its goddesses of Justice, Freedom, Equality and Fraternity. One of the representatives of this tendency is the publisher of the journal Zukunft, Dr. Hochberg, who “bought himself in” to the Party—with ‘the noblest’ intentions, I assume, but I do not give a damn for ‘intentions.’ Anything more miserable than the programme of his Zukunft has seldom seen the light of day with more ‘modest’ ‘presumption.’”8

In another letter, written almost two years later (September 19, 1879), Marx rebuts the gossip that Engels and he were behind J. Most, and he gives Sorge a detailed account of his attitude towards the opportunists in the German Social-Democratic Party. The Zukunft was run by Hochberg, Schramm and Ed. Bernstein. Marx and Engels refused to have anything to do with such a publication, and when the question was raised of establishing a new Party organ with the participation of this same Hochberg and with his financial assistance, Marx and Engels first demanded the acceptance of their nominee, Hirsch, as responsible editor to exercise control over this “mixture of doctors, students and professorial Socialists” and then directly addressed a circular letter to Bebel, Liebknecht and other leaders of the Social-Democratic Party, warning them that they would openly combat “such a vulgarisation (Verluderung—an even stronger word in German) of theory and Party,” unless the tendency of Hochberg, Schramm and Bernstein changed.

This was the period in the German Social-Democratic Party which Mehring described in his History as “a year of confusion”(Ein Jahr der Verwirrung). After the Anti-Socialist Law, the Party did not at once find the right path, first succumbing to the anarchism of Most and the opportunism of Hochberg and Co.

“These people,” Marx writes of the latter, “nonentities in theory and useless in practice, want to draw the teeth of Socialism (which they have corrected in accordance with the university recipes) and particularly of the Social-Democratic Party, to enlighten the workers, or, as they put it, to imbue them with ‘elements of education’ from their confused half-knowledge. and above all to make the Party respectable in the eyes of the petty bourgeoisie. They are just wretched counter-revolutionary windbags.”

The result of Marx’s “furious” attack was that the opportunists retreated and—effaced themselves. In a letter of November 19, 1879. Marx announces that Hochberg has been removed from the editorial committee and that all the influential leaders of the Party—Bebel, Liebknecht, Bracke, etc.—have repudiated his ideas. The Social-Democratic Party organ, the Social-Democrat, began to appear under the editorship of Vollmar, who at that time belonged to the revolutionary wing of the Party. A year later (November 5, 1880), Marx relates that he and Engels constantly fought the “miserable” way in which the Social-Democrat was conducted and often expressed their opinion sharply (wobei’s oft scharf hergeht). Liebknecht visited Marx in 1880 and promised that there would be an “improvement” in all respects.

Peace was restored, and the war never came out into the open. Hochberg retired, and Bernstein became a revolutionary Social-Democrat—at least until the death of Engels in 1895.

On June 20, 1882, Engels writes to Sorge and speaks of this struggle as already a thing of the past:

“In general, things in Germany are going splendidly. It is true that the literary gentlemen in the Party tried to cause a reactionary swing, but they failed ignominiously. The abuse to which the Social-Democratic workers are being everywhere subjected has made them everywhere more revolutionary than they were three years ago….These gentlemen [the Party literary people] wanted at all costs to beg for the repeal of the Anti-Socialist Law by mildness and meekness, fawning and humility, because it had summarily deprived them of their literary earnings, As soon as the law is repealed…the split will apparently become an open one, and the Vierecks and Hochbergs will form a separate Right wing, where they can he treated with from time to time until they definitely come a cropper. We announced this immediately after the passage of the Anti-Socialist Law, when Hochberg and Schramm published in the Jahrbuch what was under the circumstances a most infamous judgment of the work of the Party and demanded more cultivated [jebildetes instead of gebildetes. Engels is alluding to the Berlin as the German literary people], refined and elegant behaviour of the Party.”

This forecast of a Bernsteiniad made in 1882 was strikingly confirmed in 1898 and subsequent years.

And since then, and particularly after Marx’s death, Engels, it may be said without exaggeration, was untiring in his efforts to straighten out what the German opportunists had distorted.

The end of 1884. The “petty-bourgeois prejudices” of the German Social-Democratic Reichstag deputies, who voted for the steamship subsidy (Dampfersubvention, see Mehring’s History) are condemned. Engels informs Sorge that he has to correspond a great deal on this subject (letter of December 31, 1884).

1885. Giving his opinion of the whole business of the Dampjfersubvention, Engels writes (June 3) that “it almost came to a split.” The “philistinism” of the Social-Democratic deputies was “colossal.” “A petty-bourgeois Socialist fraction is inevitable in a country like Germany,” Engels says.

1887. Engels replies to Sorge, who had written that the Party was disgracing itself by electing such deputies as Viereck (a Social-Democrat of the Hochberg type). There is nothing to be done—Engels excuses himself—the workers’ party cannot find good deputies for the Reichstag.

“The gentlemen of the Right wing know that they are being tolerated only because of the Anti-Socialist Law, and that they will be thrown out of the Party the very day the Party secures freedom of action again.”

And, in general, it is preferable that “the Party be better than its parliamentary heroes, than the other way round” (March 3. 1887). Liebknecht is a conciliator—Engels complains—he always glosses over differences by phrases. But when it comes to a split, he will be with us at the decisive moment.

1889. Two International Social-Democratic Congresses in Paris. The opportunists (headed by the French possibilists) split away from the revolutionary Social-Democrats. Engels (he was then sixty-eight years old) flings himself into the fight like a young man. A number of letters (from January 12 to July 20, 1889) are devoted to the fight against the opportunists. Not only they, but also the Germans—Liebknecht, Bebel and others—are flagellated for their conciliationism.

The possibilists have sold themselves to the government, writes Engels on January 12, 1889. And he accuses the members of the British Social-Democratic Federation of having allied themselves with the possibilists.

“The writing and running about in connection with this damned congress leave me no time for anything else.” (May 11, 1889.) The possibilists are busy, but our people are asleep, Engels writes angrily. Now even Auer and Schippel are demanding that we attend the possibilist congress. But this “at last” opened Liebknecht’s eyes. Engels, together with Bernstein, writes pamphlets (signed by Bernstein—Engels calls them “our pamphlets”) against the opportunists.

“With the exception of the S.D.F., the possibilists have not a single Socialist organisation on their side in the whole of Europe. [June 8, 1889.] They are, consequently, falling back on the non-Socialist trade unions [let the advocates of a broad labour party, of a labour congress, etc. in our country take note!]. From America they will get one Knight of Labour.”

The opponent is the same as in the fight against the Bakunists:

“Only with this difference that the banner of the anarchists has been replaced by the banner of the possibilists. There is the same selling of principles to the bourgeoisie for concessions in retail, namely, for well-paid jobs for the leaders (on the town councils, labour exchanges, etc.).”

Brousse (the leader of the possibilists) and Hyndman (the leader of the S.D.F., which had united with the possibilists) attack “authoritarian Marxism” and want to form the “nucleus of a new International.”

“You can have no idea of the naiveté of the Germans. It has cost me tremendous effort to explain even to Bebel what it really all means.” (June 8, 1889.)

And when the two congresses met, when the revolutionary Social-Democrats numerically exceeded the possibilists (united with the trade unionists, the S.D.F., a section of the Austrians, etc.), Engels was jubilant (July 17, 1889). He was glad that the conciliatory plans and proposals of Liebknecht and others had failed (July 20, 1889).

“It serves our sentimental conciliatory brethren right, that for all their amicableness, they received a good kick in their tenderest spot. This will cure them for some time.”

…Mehring was right when he said (Der Sorgesche Briefwechsel) that Marx and Engels had not much of an idea of “good manners.”

“If they did not think long over every blow they dealt, neither did they whimper over every blow they received. ‘If you think that your pinpricks can pierce my old, well-tanned and thick hide, you are mistaken,” Engels once wrote.”

And the imperviousness they had themselves acquired they attributed to others as well, says Mehring of Marx and Engels.

1893. The flagellation of the “Fabians,” which suggests itself—when passing judgment on the Bernsteinists (for was it not with the “Fabians” in England that Bernstein “reared” his opportunism?).

“The Fabians are an ambitious group here in London who have understanding enough to realise the inevitability of the social revolution, but who could not possibly entrust this gigantic task to the rough proletariat alone and are therefore kind enough to set themselves at the head. Fear of the revolution is their fundamental principle. They are the ‘educated’ par excellence. Their Socialism is municipal Socialism; not the nation but the municipality is to become the owner of the means of production, at any rate for the time being. This Socialism of theirs is then represented as an extreme but inevitable consequence of bourgeois Liberalism, and hence follow their tactics of not decisively opposing the Liberals as adversaries but of pushing them on towards Socialist conclusions and therefore of intriguing with them, of permeating Liberalism with Socialism, of not putting up Socialist candidates against the Liberals, but of fastening them on to the Liberals, forcing them upon them, or deceiving them into taking them. That in the course of this process they are either lied to and deceived themselves or else betray Social. ism, they do not of course realise.

“With great industry they have produced amid all sorts of rubbish some good propagandist writings as well, in fact the beet of the kind which the English have produced, But as soon as they get on to their specific tactics of hushing up the class struggle it all turns putrid. Hence too their fanatical hatred of Marx and all of us—because of the class struggle.

“These people have of course many bourgeois followers and therefore money…”9

A CLASSICAL JUDGMENT OF THE OPPORTUNISM OF THE INTELLECTUALS IN SOCIAL-DEMOCRACY

1894, The Peasant Question.

“On the Continent,” Engels writes on November 10, 1894, “success is developing the appetite for more success, and catching the peasant, in the literal sense of the word, is becoming the fashion, First the French in Nantes declare through Lafargue not only…that it is not our business to hasten…the ruin of the small peasant which capitalism is seeing to for us, but they also add that we must directly protect the small peasant against taxation, usurers and landlords. But we cannot co-operate in this, first because it is stupid and second because it is impossible. Next, however, Vollmar comes along in Frankfort, and wants to bribe the peasantry as a whole, though the peasant he has to do with in Upper Bavaria is not the debt-laden poor peasant of the Rhineland but the middle and even the big peasant, who exploits his men and women farm servants and sells cattle and grain in masses, And that cannot be done without giving up the whole principle.”10

1894, December 4.

“…The Bavarians, who have become very, very opportunistic and have almost turned into an ordinary people’s party (that is to say, the majority of leaders and many of those who have recently joined the Party), voted in the Bavarian Diet for the budget as a whole; and Vollmar in particular has started an agitation among the peasants with the object of winning the Upper Bavarian big peasants—people who own 25 to 80 acres of land (10 to 30 hectares) and who therefore cannot manage without wage labourers—instead of winning their farm hands.”

We thus see that for more than ten years Marx and Engels systematically and unswervingly fought opportunism in the German Social-Democratic Party and attacked intellectual philistinism and petty-bourgeoisdom in Socialism. This is an extremely important fact. The general public knows that German Social-Democracy is regarded as a model of Marxist proletarian policy and tactics, but it does not know what a constant war the founders of Marxism had to wage against the “Right wing” (Engels’ expression) of that party. And it is no accident that soon after Engels’ death this war turned from a concealed war into an open war. This was an inevitable result of the decades of historical development of German Social-Democracy.

And now we very clearly perceive the two lines of Engels’ (and Marx’s) recommendations, directions, corrections, threats and exhortations. They most insistently called upon the British and American Socialists to merge with the labour movement and to eradicate the narrow and hidebound sectarian spirit from their organisations. They most insistently taught the German Social-Democrats to be ware of succumbing to philistinism, to “parliamentary idiotism” (Marx’s expression in the letter of September 19, 1879), to petty bourgeois intellectual opportunism.

Is it not characteristic that our Social-Democratic gossips have noisily proclaimed the recommendations of the first kind and have kept their mouths shut, have remained silent over the recommendations of the second kind? Is not such one-sidedness in appraising Marx’s and Engels’ letters the best indication, in a sense, of our, Russian Social-Democratic…”one-sidedness”?

At the present moment, when the international labour movement is displaying symptoms of profound ferment and wavering, when extremes of opportunism, “parliamentary idiotism” and philistine reformism have evoked opposite extremes of revolutionary syndicalism, the general line of Marx’s and Engels’ “amendments” to British and American Socialism and German Socialism acquires exceptional importance.

In countries where there are no Social-Democratic workers’ parties, no Social-Democratic members of parliament, no systematic and consistent Social-Democratic policy either at elections or in the press, etc. Marx and Engels taught that the Socialists must at all costs rid themselves of narrow sectarianism and join with the labour movement so as to shake up the proletariat politically, for in the last third of the nineteenth century the proletariat displayed almost no political independence either in England or America. In these countries—where bourgeois-democratic historical tasks were almost entirely absent—the political arena was wholly filled by the triumphant and self-complacent bourgeoisie, which in the art of deceiving, corrupting and bribing the workers has no equal anywhere in the world.

To think that these recommendations of Marx and Engels. to the British and American labour movement can be simply and directly applied to Russian conditions is to use Marxism not in order to comprehend its method, not in order to study the concrete historical peculiarities of the labour movement in definite countries, but in order to settle petty factional, intellectual accounts.

On the other hand, in a country where the bourgeois-democratic revolution was still incomplete, where “military despotism, embellished with parliamentary forms” (Marx’s expression in his Critique of the Gotha Programme) prevailed, and still prevails, where the proletariat had long ago been drawn into politics and was pursuing a Social-Democratic policy, what Marx and Engels feared most of all in such a country was parliamentary vulgarisation and philistine compromising of the tasks and scope of the labour movement.

It is all the more our duty to emphasise and advance this side of Marxism in the period of the bourgeois-democratic revolution in Russia because in our country a large, “brilliant” and rich bourgeois-liberal press is vociferously trumpeting to the proletariat the “exemplary” loyalty, the parliamentary legalism, the modesty and moderation of the neighbouring German labour movement.

This mercenary lie of the bourgeois betrayers of the Russian revolution is not due to accident or to the personal depravity of certain past or future ministers in the Cadet11 camp. It is due to the profound economic interests of the Russian liberal landlords and liberal bourgeois. And in combating this lie, this “making the masses stupid” (Massenverdummung—Engels’ expression in his letter of November 29, 1886), the letters of Marx and Engels should serve as an indispensable weapon for all Russian Socialists.

The mercenary lie of the bourgeois liberals holds up to the people the exemplary “modesty” of the German Social-Democrats. The leaders of these Social-Democrats, the founders of the theory of Marxism, tell us:

“The revolutionary language and action of the French has made the whining of the Vierecks and Co, [the opportunist Social-Democrats in the German Reichstag Social-Democratic fraction] sound quite feeble (the reference is to the formation of a labour party in the French Chamber and to the Decazeville strike, which split the French Radicals from the French proletariat], and only Liebknecht and Bebel spoke in the last debate…and both of them spoke well. We can with this debate once more show ourselves in decent society, which was by no means the case with all of them. In general it is a good thing that the leadership of the Germans [of the international social movement], particularly after they sent so many philistines to the Reichstag (which, it is true, was unavoidable), has become rather disputable. in Germany everything becomes philistine in peaceful times; and therefore the sting of French competition is absolutely necessary.” (Letter of April 29, 1886.)

Such are the lessons which must be drawn most firmly of all by the R.S.D.L.P.,12 which is ideologically dominated by the influence of German Social-Democracy.

These lessons are taught us not by any particular passage in the correspondence of the greatest men of the nineteenth century, but by the whole spirit and substance of their comradely and frank criticism of the international experience of the proletariat, a criticism which shunned diplomacy and petty considerations.

How far all the letters of Marx and Engels were indeed imbued with this spirit may also be seen from the following passages which it is true are, relatively speaking, of a particular nature, but which on the other hand are highly characteristic.

In 1889 a young, fresh movement of untrained and unskilled labourers (gas workers, dockers, etc.) began in England, a movement marked by a new and revolutionary spirit. Engels was delighted with it. He refers exultingly to the part played by Tussy, Marx’s daughter, who agitated among these workers.

“…The most repulsive thing here.” he says, writing from London on December 7, 1889, “is the bourgeois ‘respectability’ which has grown deep into the bones of the workers. The division of society into a scale of innumerable degrees, each recognised without question, each with its own pride but also with its native respect for its ‘betters’ and ‘superiors,’ is so old and firmly established that the bourgeois still find it pretty easy to get their bait accepted. I am not at all sure, for instance, that John Burns is not secretly prouder of hie popularity with Cardinal Manning, the Lord Mayor and the bourgeoisie in general than of his popularity with his own class. And Champion—an ex-Lieutenant—has intrigued for years with bourgeois and especially with conservative elements, preached Socialism at the parsons’ Church Congress, etc. Even Tom Mann, whom I regard as the finest of them all, is fond of mentioning that he will be lunching with the Lord Mayor. If one compares this with the French, one can see what a revolution is good for after all.”13

Comment is superfluous. Another example. In 1891 there was danger of a European war. Engels corresponded on the subject with Bebel, and they agreed that in the event of Russia attacking Germany, the German Socialists must desperately fight the Russians and any allies of the Russians.

“If Germany is crushed, then we shall be too, while in the most favourable case the struggle will be such a violent one that Germany will only be able to hold on by revolutionary means, so that very possibly we shall be forced to come into power and play the part of 1793.” (Letter of October 24, 1891.)14

Let this be noted by those opportunists who cried from the housetops that “Jacobin” prospects for the Russian workers’ party in 1905 were un-Social-Democratic! Engels squarely suggests to Bebel the possibility of the Social-Democrats having to participate in a provisional government.

Holding such views on the tasks of Social-Democratic workers’ parties it is quite natural that Marx and Engels should have the most fervent faith in the Russian revolution and its great world significance. We see this ardent expectation of a revolution in Russia in this correspondence over a period of nearly twenty years.

Here is Marx’s letter of September 27, 1877, He is quite enthusiastic over the Eastern crisis:

“Russia has long been standing on the threshold of an upheaval, all the elements of it are prepared…The gallant Turks have hastened the explosion by years with the thrashing they have inflicted…The upheaval will begin secundum artem [according to the rules of the art] with some playing at constitutionalism and then there will be a fine row (et il y aura un beau tapage). If Mother Nature is not particularly unfavourable towards us we shall still live to see the fun!”15 (Marx was then sixty-one years old.)

Mother Nature did not—and could not very well—permit Marx to live “to see the fun.” But he foretold the “playing at constitutionalism,” and it is as though his words were written yesterday in relation to the First and Second Russian Dumas. And we know that the warning to the people against “playing at constitutionalism” was the “living soul” of the tactics of boycott so detested by the liberals and opportunists…

Here is Marx’s letter of November 5, 1880. He is delighted with the success of Capital in Russia, and takes the part of the Naredovoltsi against the newly-arisen group of Chernoperedeltsi. Marx correctly perceives the anarchistic elements in the latter’s views. Not knowing and having then no opportunity of knowing the future evolution of the Chernoperedeltsi-Narodniki into Social-Democrats, Marx attacks the Chernoperedeltsi with all his trenchant sarcasm:

“These gentlemen are against all political-revolutionary action. Russia is to make a somersault into the anarchist-communist-atheist millennium! Meanwhile, they are preparing for this leap with the most tedious doctrinairism, whose so-called principles are being hawked about the street ever since the late Bakunin.”

We can gather from this how Marx would have judged the significance for Russia of 1905 and the following years of the “political-revolutionary action” of Social-Democracy.16 Here is a letter by Engels dated April 6, 1887:

“On the other hand, it seems as if a crisis is impending in Russia. The recent attentats rather upset the apple-cart…”

A letter of April 9, 1887, says the same thing…

“The army is full of discontented, conspiring officers. [Engels at that time was influenced by the revolutionary struggle of the Narodnaya Volya party; he set his hopes on the officers, and did not yet see the revolutionary Russian soldiers and sailors, who manifested themselves so magnificently eighteen years later…] I do not think things will last another year; and once it breaks out (losgeht) in Russia, then hurrah!”

A letter of April 23, 1887:

“In Germany there is persecution [of Socialists] after persecution. It looks as if Bismarck wants to have everything ready, so that the moment the revolution breaks out in Russia, which is now only a question of months, Germany could immediately follow her example (losgeschlagen werden).”

The months proved to be very, very long ones. Doubtless, philistines will be found who, knitting their brows and wrinkling their foreheads, will sternly condemn Engels’ “revolutionism,” or will indulgently laugh at the old utopias of the old revolutionary exile.

Yes, Marx and Engels erred much and often in determining the proximity of revolution, in their hopes in the victory of revolution (e.g., in 1848 in Germany), in their faith in the imminence of a German “republic” (“to die for the republic,” wrote Engels of that period, recalling his sentiments as a participant in the military campaign for an imperial constitution in 1848-49). They erred in 1871 when they were engaged in “raising revolt in Southern France, for which” they (Becker writes “we,” referring to himself and his nearest friends: letter No. 14, of July 21, 1871) “did, sacrificed and risked all that was humanly possible…” The same letter says:

“If we had had more means in March and April we would have roused the whole of Southern France and would have saved the Commune in Paris.”

But such errors—the errors of the giants of revolutionary thought who tried to raise and did raise the proletariat of the whole world above the level of petty, commonplace and trifling tasks—are a thousand times more noble and magnificent and historically more valuable and true than the puerile wisdom of official liberalism, which sings, shouts, appeals and exhorts about the vanity of revolutionary vanities, the futility of the revolutionary struggle and the charms of counter-revolutionary “constitutional” fantasies…

The Russian working class will win its freedom and give a fillip to Europe by its revolutionary action, full though it may be of mistakes—and let the philistines pride themselves on the infallibility of their revolutionary inaction.

April 6, 1907

Notes

1. The Sorge Correspondence,” Neue Zeit, 25th year, Nos. 1 and 2. Trans.

2. See Letters of Karl Marx to Dr. Kugelmann, translation edited by N. Lenin, with a foreword by the editor, St. Petersburg, 1907.

3. Marx-Engels Selected Correspondence, p. 450. Trans.

4. Ibid., p, 455. Trans.

5. Ibid, p. 454. Trans.

6. Ibid., pp. 453-54. Trans.

7. Ibid, p. 450. Trans.

8. Ibid., p. 350. Trans.

9. Ibid., pp. 505-06. Trans.

10. Ibid, p. 525. Trans.

11. Constitutional-Democrats. Ed.

12. Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party. Trans.

13. Ibid., p. 461. Trans.

14. bid., p. 494. Trans.

15. Ibid., p. 48. Trans.

16. By the way, if my memory does not deceive me, Plekhanov or V.I. Zasulich told me in 1900-03 about the existence of a letter of Engels to Plekhanov on Our Differences and on the character of the impending revolution in Russia. It would be interesting to know precisely—is there such a letter, does it still exist, and is it not time to publish it? Lenin.

PDF of Selected Works: https://archive.org/download/selected-works-vol.-11/Selected%20Works%20-%20Vol.%2011.pdf

PDF of Sorge Correspondence (in Russian): https://archive.org/download/pisma_i_f_bekkera_i_ditcgena__f_engelsa_k_marksa_i_dr_k_f_a_zorge_i_dr./pisma_I_F_Bekkera_I_Ditcgena__F_E%60ngelsa_K_Marksa_i_dr_k_F_A_Zorge_i_dr..pdf