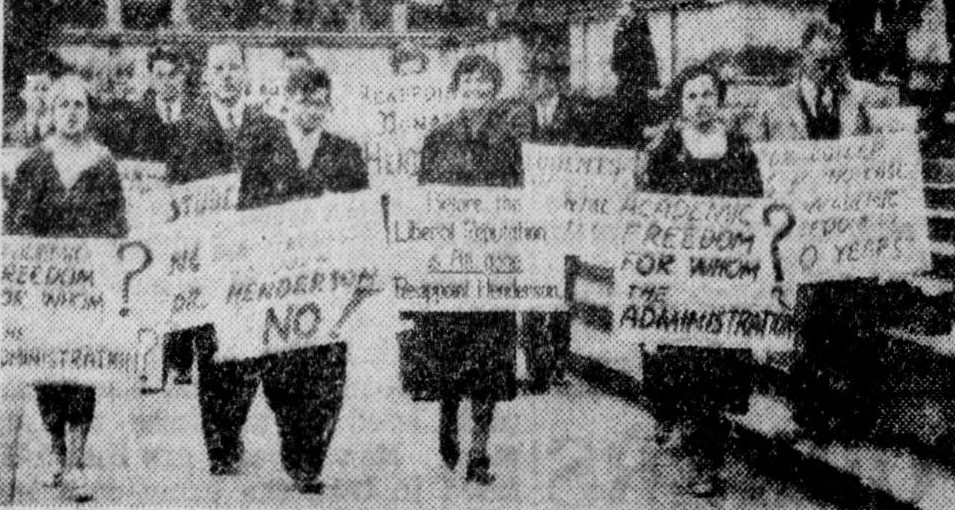

As part of the larger suppression of a growing campus radicalism in the early 1930s, left wing teachers were a target for dismissal. Donald Henderson was an economic instructor at Columbia University and National Student League leader fired for his political activity leading to mass demonstrations and student strikes.

‘The Case of Donald Henderson’ by Jerome David from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 2 No. 7. May, 1933.

“STUDENTS are only incidental” to the University, President Nicholas Murray Butler blandly informed a delegation from the Joint Committee for the Reinstatement of Donald Henderson. And yet these “incidentals” to the normal business of the university: trustee meetings, million dollar drives, the harmless interplay of ideals in the vacuum of the lecture hall—have in the past few weeks attempted to take a decisive hand in the management of university affairs. An angry student protest against the shameful dismissal of Donald Henderson is rapidly becoming nation-wide. And the volume of this protest has forced the Columbia Administration to bring forward one irrelevancy after another in a fruitless attempt to justify its action.

Columbia University has descended to the shameful level of defending the dismissal of Donald Henderson on the grounds that he is “an incompetent teacher.” President Butler has added the canard that he was allowed to keep his post thus far only because of “pity.” Thus the founder and organizer of the National Student League, the leader of the Kentucky delegation, an organizer of the Chicago Anti-War Congress, a fighter for academic freedom in every place where student expression is stifled,—in short, a man who has done more than any other to build a militant American student movement, and who has had a greater influence on student opinion than any other instructor in the country, is being removed on the grounds that he is unable to teach, unable to stir the student mind to thought and action. One would think that the Columbia authorities would have seen at once the absurdity of this line of defense, but the university finds itself in a difficult position where cogent defenses are not easy to find.

“No issue of academic freedom is involved,” President Butler assured the student delegation. “I have been here fifty years and I have never seen a case of suppression of academic freedom.” The memory of a university president who lauded the Kaiser before America’s entrance into the War, became an intolerant patriot who ferretted out German influences on the Campus after War was declared, in order to reemerge with the turn in the tide of world opinion as one of the leading doves of international peace, must be conveniently short; and the remembrance of Dana, Robinson, and other professors hounded off the campus during wartime appears to have left him. The enlightened President does not “care a rap what you do. You can turn handsprings on 116th Street. Anybody’s views on any subject have nothing to do with his appointment or re-appointment, as long as he behaves like a gentleman and does his work.” This is in a certain sense true. The crime of Don Henderson is not that he has “entertained” radical ideas, for this is permissible; his offense is that he has fought for them, and has sought to put them into practice. Instead of talking, Henderson acted; instead of limiting himself to the classroom, he carried the classroom out into the world. He roused the American students from an alarming apathy and awakened an unexpected intelligence. For this he is expelled.

The liberalism of Columbia University which considers that “a university exists for the pursuit of truth. Students are only incidental” is a tolerance of ideas only when they are disrupted from practical life and rendered ineffectual. ‘This is the meaning of that sonorous and Delphic phrase which rolled off the President’s lips last week. An Economics Department whose members endorse the right of American labor to union organization, and the principle of the minimum wage, but when scandalously low wages are paid to the employees of Columbia, and an attempt at union organization is viciously attacked by the University, piously avert their heads and do nothing,—presents an example of that form of academic freedom which Columbia finds such a convenient and harmless ornament.

The University has erected three lines of defense.

1. Donald Henderson’s appointment was not permanent. The University as usual buries its head under an irrelevancy. It is contended that the University follows a policy of keeping instructors only two years unless they obtain a Ph.D. degree or a promotion. But of the 50 instructors at Columbia without doctors’ degrees, 33 have served four years or more.

2. The University claims that Henderson was given two years to complete his Ph.D., and was engaged on that understanding. As against this contention, we have the advice of Professor Tugwell, then head of the Economics Department, who told Henderson to take five years for his doctorate if necessary.

3. The final charge of the Administration that Donald Henderson was a poor teacher is nothing more than a wretched slander.

We quote from the statement of the Columbia Joint Committee for the reappointment of Donald Henderson:

“’Poor teacher.’ This is the most contemptible charge of all, unsupported by facts. Prof. McCrea says, “Henderson has failed consistently to apply himself seriously and diligently to his duties as instructor and to maintain the standards of teaching required by the department.” Consider this in the light of signed statements by former students who are neither personal friends of Henderson or associated with his political activities, including honor students, football players and others: “I will always be glad to say that Mr. Henderson was easily one of my best teachers during my freshman year at Columbia.”—Michael Demshar. “—As capable an instructor as any under whom I have worked at Columbia with but few exceptions.”— Frank J. McGovern. “If every teacher in Columbia College had as stimulating a personality and as critical a mind as Mr. Henderson has, the level of the faculty would be raised very considerably.”— C.J.O. Hanser. The students of the Junior Seminar in economics voted unanimously and on their own initiative that Henderson has shown himself a competent instructor and “his analysis of economic theory has been illuminating and intellectually stimulating.” It should be added that the administration’s charge concerning Mr. Henderson’s lack of diligent application to duties, even if it were supported (which it is not) sounds very strange in view of the well known presence of full professors in the “Little Cabinet” in Washington who make occasional flying trips to the campus and who are still drawing full salaries from the University. Washington-Columbia “Brain Trust” has not even received an official leave of absence from the University.”

The true reasons for Henderson’s dismissal are obvious. He made use of the right of freedom of speech and action, which a Columbia instructor supposedly possesses, for purposes inacceptable to the rulers of the university. He defended the principle of academic freedom wherever it was violated, not by means of issuing statements, but by fighting the issue side by side with the students. He fought for a revolutionary alliance of workers and students against the interests of the capitalist system. This, to the millionaire rulers of Morningside Heights was unforgivable. A brief study of the personnel of the Board of Trustees shows that it is composed almost exclusively of corporation directors, representing the three largest banks in the nation, the steel and telephone trusts, and the leading corporations in almost every important industry. How could such a group be expected to tolerate a communist?

No. Henderson was not dismissed because of poor teaching. He was removed because he taught the contraband doctrine of Marxism-Leninism. Because he agitated inside and outside the classroom, and agitated too persuasively and too well. He practiced too closely that unity of thought and action preached by Columbia’s patron philosopher, John Dewey. He followed the advice also of President Butler who urged Columbia men to participate more actively in community life. He was fired because he used welded theory and practice, not to help Wall Street regain its profits, but to expose the bankruptcy of the trustees of Columbia University, and the system they represent, because he showed the way to struggle against their system, and joined in the struggle.

The unity of theory and practice, typified by the actions of the little clique of Columbia teachers, who form the Roosevelt “kitchen cabinet,” who are known as the “President’s brains,” is thoroughly approved of, and brings only credit to the University. The absences of Tugwell, Moley, and consorts, who fly back and forth between Washington and New York in piddling little attempts to help keep the capitalist system going a little while longer, are not brought to the attention of the Administration to be used against them. The revolutionary activity of Henderson—that of course is a different matter.

Donald Henderson has done more for students in one year than Columbia University has ever accomplished in its whole history. As Executive Secretary of the National Students League he fought for the reinstatement of Reed Harris, for the rights of students to enter Kentucky, for unity of students with workers and in every way carried out the principles advocated by President Butler. Instead of talking he acted, instead of limiting himself to the classroom, he carried the classroom out into the world. He roused the American students from an alarming apathy and awakened an unexpected intelligence. For this he is expelled. He is a leader, and the Board of Trustees is afraid of a leader. He fights with skilled weapons against their clumsy bludgeon—ignorance. His reinstatement is necessary to us. We must fight now as a unit more fiercely than in the past and more pressingly. We know our weapons—let us use them!

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of original issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1933-05_2_7/student-review_1933-05_2_7.pdf