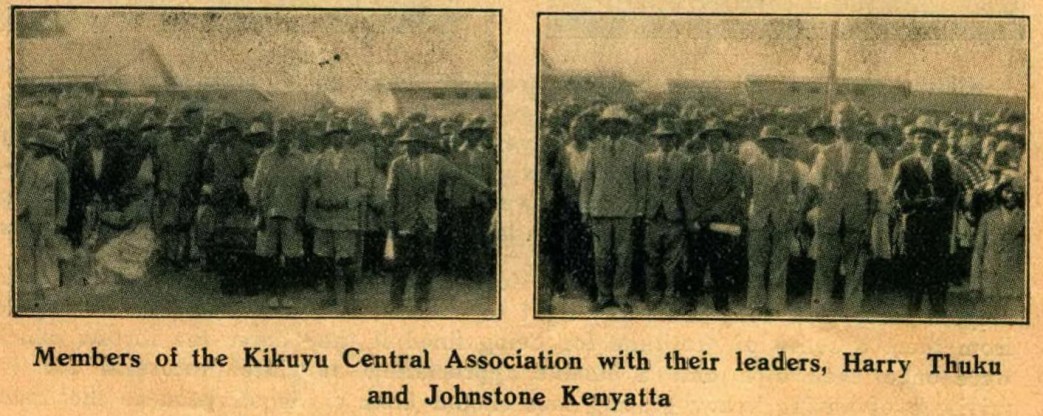

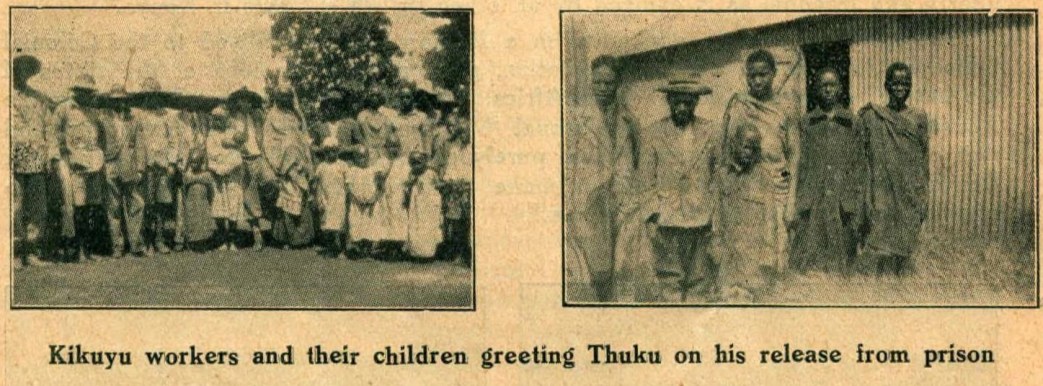

The British Empire’s practice in today’s Kenya and the work of Harry Thuku and the Kikuyu Central Association to redress the seizure of the land and peonization of the population.

‘The Situation Kenya’ by J.E. from The Negro Worker. Vol. 2 No. 8. August 15, 1932.

Kenya is the classical land of British imperialism. In no part of the Empire, with the possible exception of South Africa do we find such outrageous manifestations of imperialist oppression, as in Kenya. The following facts glaringly reveal the terrible conditions under which the natives live.

“The Kenya African must be registered and have his finger prints taken, a duplicate of this certificate being kept at the Government offices. Whenever he wishes to enter a town he must obtain a special permit and he must produce this certificate when applying for employment. This must be endorsed by the master on leaving, and if for any reason, either just or unjust, the master refuses this endorsement, he cannot obtain an engagement elsewhere. These regulations make Kenya Africans strangers in their own land; they subject Africans to a control which is only accorded to criminals in other countries, and which gives rise to constant hardship and resentment. We urge that Africans be accorded the same liberty and freedom as is enjoyed by all other British subjects in Kenya.”

The inclusion of such a demand in a Memorandum submitted to the Colonial Office by the Kikuyu Central Association, gives at once an idea of the status of the native workers in British East Africa. In the debate on the Colonies in the House of Commons, on July 1, Colonel Wedgwood stated: “We cannot pretend that our work (in Kenya) has been purely one of benevolence. The natives in Kenya have got to work; and we make them work. They have to work two months for a master to pay their tax.”

This is merely another way of stating the official policy of British imperialism in East Africa as formulated by Sir Percy Girouard, when he was Governor of Kenya: “Taxation is the only method of compelling the natives to leave their reserves for the purpose of seeking work. Only in this way can the cost of living be increased for the natives. It is on this that the supply of labour and the price of labour depends.”

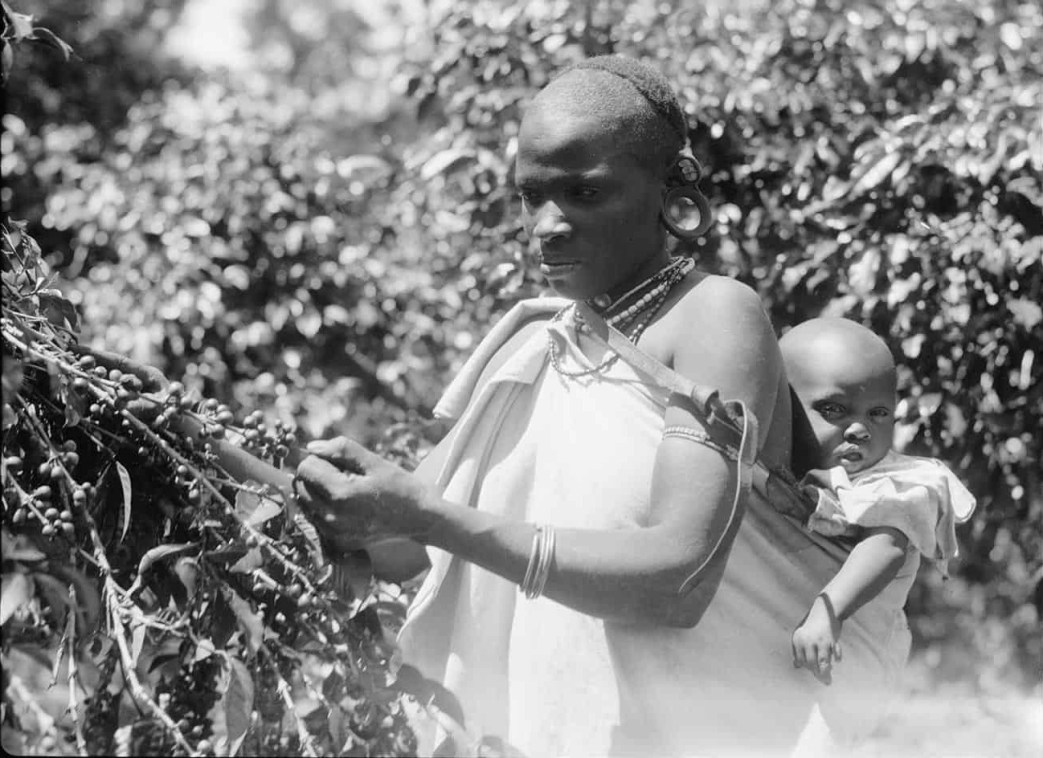

The climate of British East Africa is suitable for white settlement, and the main method of exploiting the country’s resources is by the running of plantations, owned by the whites, and worked by native labour.

It must be remembered that all the land was taken from the natives in the first place by force and they were driven into reserves. By taking land from the native and by imposing a poll-tax on him the British farmers are assured of a supply of cheap labour.

The annexation of land, even that which has been set aside for Native Reserves, still continues.

The Kikuyu Memorandum gives concrete instances of this land robbery. Valuable land at Maragwa-Tana has been taken for the purposes of erecting an electric power station, which is to be a private dividend-paying undertaking, financed by the proprietors of the local Sisal Mills.

“Before the land at Maragwa-Tana was ear-marked as a Water-Power Reserve, there were upon it 280 dwelling huts, 335 storage barns and 195 cattle pens belonging to the Kikuyu. These were all razed to the ground to clear the site. On the stretch of river taken there was a good ford where the Kikuyu crossed to trade with the Wakamba. Now they have to go 20 or 30 miles to another ford. Since this land has been taken many Kikuyu have been arrested and fined heavily (from 250 shillings upwards) for trying to use the ford.”

Thousands of the Kikuyu tribe have thus been rendered homeless, without any sort of redress for the callous expropriation of their lands. Moreover, the land surveys under which the Kikuyu were dispossessed were made in secret and many areas were declared to be Crown land without the knowledge of the owners.

Strange that the white rulers who deem the “n***rs” incapable of any civic responsibility, and deny them any right to control their own lives, should expect from them a sense of gratitude for being fined if they enter the forests which were once their own, and a humble appreciation of white protection for the privilege of paying heavy grazing fees should their cattle stray on to the lands they know should still be theirs!

The missionaries have sanctimoniously played their part in the exploitation of the Kikuyu and other tribes. They took from the natives land for mission sites, money to erect mission schools and to equip them. Then, secretly, they got licenses from the Government giving them sole rights in the property that the natives had provided! Protected from the Government, which incidentally has evaded its responsibility to provide native schools, the mission authorities proceeded to exclude from the classes any native children whose parents objected to the inculcation of western religious beliefs, and even brought prosecutions against those parents who entered the premises or precincts on charges of trespassing, which meant heavy fines and imprisonment with hard labour…for such is the power of the missions!

So close, in fact, is the harmony between the imperialist Government and the religious bodies that one wonders whether a text did not precede the infamous “Northly Land Circular”. This document, issued to native chiefs, after calling upon native authorities (chiefs and headsmen) to use their influence to induce all young men to enter the labour market (virtual slavery on the plantations) stated “that where farms and plantations are situated in the vicinity of a native area, women and children should be encouraged to go out for such labour as they can perform.”

As a result of this “Suffer-little-children-to-come-unto-me” effort, 70,000 women and 150,000 children were assigned to European farms in Kenya.

All rights to freedom of speech, free Press, and liberty to hold meetings are denied the Kenyan Africans. For the Kikuyu people, as for other African tribes, the advent of British colonisation has meant annexation of tribal lands, the imposition of taxes that compel them to hire their labour to the white settlers, and submission to a whole series of Ordinances that are arrived at entirely without any native expression of opinion, which are not even made known to the natives by publication in their own language, but which are enforced with the utmost severity.

The Kikuyu Memorandum to the Colonial Office quotes Criminal Case No. 83/29, heard at Fort Hall, Kenya, when a Kikuyu named Daniel Kangori, a member of the Local Native Council, was arrested with two others for being found conversing in a house after an evening meal. After they were convicted the judge added: “I order accused (1) and (2) to refrain from visiting accused (3).”

Realizing that one of the most potent methods of subjecting their race has been the appointment of puppet chiefs, under the thumb of the British authorities, the Kikuyu demand that the chiefs should be elected by the natives themselves in each district.

Valuable as the Memorandum of the Kikuyu Central Association is for its categorical statement of the natives’ demands, it would be futile to imagine that the presentation of any such document at Whitehall will bring any alleviation. Paper cuts no ice. Only mass political activity of the native toilers, supported by the solidarity of white workers in the “home” country can transform the Dark Africa of imperialist exploitation into an enlightened country of freedom for workers, both black and white.

First called The International Negro Workers’ Review and published in 1928, it was renamed The Negro Worker in 1931. Sponsored by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a part of the Red International of Labor Unions and of the Communist International, its first editor was American Communist James W. Ford and included writers from Africa, the Caribbean, North America, Europe, and South America. Later, Trinidadian George Padmore was editor until his expulsion from the Party in 1934. The Negro Worker ceased publication in 1938. The journal is an important record of Black and Pan-African thought and debate from the 1930s. American writers Claude McKay, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, and others contributed.

Link to full PDF of issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1932-v2n8-aug-15th.pdf