A classic account from the Women’s Trade Union League’s Martha Bensley Bruere of the March 25, 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in which 146 workers died in a conflagration at the New York sweatshop, its doors locked to ‘prevent theft’ and only one fire-escape.

‘The Triangle Fire’ by Martha Bensley Bruere from Life and Labor (W.T.U.L.). Vol. 1 No. 5. May, 1911.

The Triangle Shirt Waist Shop in New York City, which was the scene of the great fire on March 25th, when 143 workers were killed, was also the starting point of the strike of the forty-thousand shirt waist workers in 1909.

The girls struck because they wished to stand together for decent shop conditions, wages on which they could live and reasonable hours, and neither Mr. Harris nor Mr. Blanck, both of whom were members of the Manufacturers’ Association, would allow their workers to unite in any way at all.

It happened that I did picket duty morning and night before that shop and saw the striking girls go up to the strike-breakers and ask timidly:

“Don’t you know there’s a strike by the Triangle”

It was before this Triangle Shop that the girls were clubbed by the police and by the hired thugs who assisted them; and it was in the streets around it that a large number of arrests were made. The girl pickets were dragged to court, but every one from this shop was discharged. The police and the government of the city had banded themselves together to protect the property of Harris and Blanck, the Triangle Shirt Waist firm.

The six hundred girls who worked at the Triangle Shop were beaten in the strike. They had to go back without the recognition of the union and with practically no change in conditions. On the 25th of March it was these same policemen who had clubbed them and beaten them back into submission, who kept the thousands in Washington Square from tramping upon their dead bodies, sent for the ambulances to carry them away, and lifted them one by one into the receiving coffins which the Board of Charities sent down in wagon loads.

I was coming down Fifth Avenue on that Saturday afternoon when a great swirling, billowing cloud of smoke swept like a giant streamer out of Washington Square and down upon the beautiful homes in lower Fifth Avenue. Just as I was turning into the Square two young girls whom I knew to be working in the vicinity came rushing toward me, tears were running from their eyes and they were white and shaking as they caught me by the arm.

“Oh,” shrieked one of them, “they are jumping.”

“Jumping from ten stories up! They are going through the air like bundles of clothes and the firemen can’t stop them and the policemen can’t stop them and nobody can’t help them at all!”

“Fifty of them’s jumped already and just think how many there must be left inside yet”–and the girls started crying afresh and rushed away up Fifth Avenue.

A little old tailor whom I knew came shrieking across the Square, tossing his arms and crying, “Horrible, horrible.” He did not recognize me, nor know where he was; he had gone mad with the sight. The minister of a fashionable church sank limp and white on one of the park benches and covered his face with his hands, unable to face the horror. For four blocks to the east the streets ran ankle deep with the water from the fire engines, and the crowd surged back and forth, breaking in repeated panics as ambulances and automobiles filled with injured and dead rushed through.

The police tried to keep the fire lines. The reserves were called out and formed into a cordon of blue backs against the surging crowd, but the Triangle shop was just on the edge of the quarter where live half a million Italians; the working day was over and thousands of factory workers were pouring into Washington Square on their way home, the mass of workers pressed in and in on the fire lines, and what can policemen do against a whole quarter mad with terror at seeing its sisters and daughters burned before its eyes? Can you quiet a man who thinks that the charred mass over which a merciful blanket has just been thrown, is his newly married wife? Sometimes the mob shrieked that the still forms on the pavement were not dead; sometimes they raged at the firemen because they did not do the impossible, for the extension ladders only reached to the sixth story, while the fire was on the eighth, ninth and tenth–the scaling ladders were useless–the girls jumped so rapidly and so many together that the life nets broke through, and as Battalion Chief Worth said afterward:

“There was no apparatus in the department which could have been of service.” The city government which, through its policemen and detectives had compelled the girls to go back to work at the Triangle Shop, was quite powerless to save their lives.

But why did the girls jump to death? Why did they wait and burn in their workrooms? Why didn’t they leave the building? Said Sadie Bergida:

“We all ran for the Washington Place door. When we tried to open it we found it was locked. The flames were racing up behind us and the room was filled with smoke. We girls struggled desperately to force open the door; there was a snap lock on the inside, however, and it held till Mr. Brown, a machinist, ran up and throwing his body against the door, burst it open. But most of the girls by that time had rushed to the Greene Street door. Of what happened after that I have only a very faint recollection. It seems to me that I tumbled down the stairs to the street.”

Said Tessa Benani:

“My sister Sarah and I worked along side of each other and our cousin Josey worked a little ways off. We ran with about forty other girls to the Washington Place doors and found them locked, and we beat on those iron doors with our bare hands and tried to tear off the big padlock. The girls behind us were screaming and crying. Several of them, as the flames crept up closer, ran into the smoke, and we heard them scream as the flames caught their clothes. One little girl, who worked at the machine opposite me, cried out in Italian, “Good-bye, good-bye.” have not seen her since. My cousin Josey staggered through the mob and made direct for the flames. The next I heard of her was when they brought her body home from the morgue. She had jumped! Half a dozen other girls went into the flames that were eating up the Greene Street side. They all jumped from the windows.”

Tessa and Sarah Benani also escaped when William Brown broke open the door. Around the entrance to the freight elevator which the girls were expected to use was a partition with a narrow door through which the girls could only pass one at a time. Some of the girls did not even know of the existence of the passenger elevator reserved for officials of the firm, which might have saved them. There was a small stairway to the roof by which N. Harris and Blanck and a few of their relatives escaped; but I have been unable to discover that any of the employees even knew of its existence.

There were two reasons why these three natural exits, the doors to the stairway, the elevator, and the roof were obstructed; first, to guard against a sudden exodus of employees in concerted protest; second, to prevent the girls stealing anything. Said Ida Deutchman:

“This is the worst shop I ever worked in. When applying for work you must undergo a half hour examination about union affiliations. When a girl was hired, after working at the machine she would again be asked by the man in charge of the floor if she was a member of the Union. For the five months I worked in the shop I saw women come and go on account of the spy system they have.

“When leaving work they have men at the Greene Street door searching all the girls. We were made to open our pocket-books, and when a girl didn’t do it she was made to come up two or three flights and show that she didn’t have a piece of lace or anything else. A girl could not carry a waist in her pocketbook, and all one could steal was a piece of lace or embroidery worth two to three cents. Leaving work we were treated worse than prisoners.”

After the fire a member of the Women’s Trade Union League consulted a fire expert as to what could be done about locked doors such as these, which are plenty enough in New York. Said he:

“Yes, the doors ought to be open, of course. It’s all right to talk about it. But practically, you know–practically it can’t be done! Why, if you had doors open so that the girls could come and go, they might get away with a lot of stuff. Why, the doors have got to be locked. Haven’t you got to protect the manufacturer?”

And this not a week after the fire! But there is still the question:

“Why didn’t the girls come down the fire escape? There was one, wasn’t there?”

Yes, there was one–just one! According to the official report, if there had been no fright or panic this fire escape would have emptied the building in three hours. The girls were all dead in twenty minutes!

Then again why did not the girls use the fire extinguishers apparatus required by law to be put in buildings of that class?

Said Mr. Harris of the firm on the witness stand:

“I can truthfully say that I never saw a length of hose or stand-pipe in the building.”

An order had gone out to install automatic sprinklers in factories, but the manufacturers had organized to fight it because it meant so great an expenditure.

No! there seems to be no doubt of the reasons which prevented the girls from either using the fire escape or putting out the fire themselves.

Well, the fire is over, the girls are dead, and as I write the procession in honor of the unidentified dead is moving by under my windows. Now what is going to be done about it?

Harris and Blanck, the Triangle Company, have offered to pay one week’s wages to the families of the dead girls–as though it were summer and they were giving them a vacation! Three days after the fire they inserted in the trade papers this notice:

“NOTICE, THE TRIANGLE WAIST CO. beg to notify their customers that they are in good working order. HEADQUARTERS now at 9-11 University Place.”

The day after they were installed in their new quarters, the Building Department of New York City, discovered that 9-11 University Place was not even fire proof and that the firm had already blocked the exit to the one fire escape by two rows of sewing machines, 75 in a row, and that at the same time repairs were begun on the old quarters in the burned building under a permit which called for no improvements or alterations of any conditions existing before the fire. It called for repairs only, which means, it was generally conceded, that the place would be re-opened in the same condition it was in before the fire.

That is what the employers have done. The public has held meetings of protest–many of them. It has passed resolutions and subscribed over $80,000, to be expended through the Red Cross Society and a Citizens’ Committee formed for the purpose.

What have the girls, working through their union, done for themselves? $15,000 was collected by the Ladies’ Waist Makers’ Union, the Forwards and the W.T.U.L. for the relief of the bereft families.

Early on the morning of the day after the fire, a meeting of the Executive Board of the Ladies Waist and Dressmakers’ Union was called, and relief work begun, no one knowing better than the girls who worked in the same trade what it meant to a family when the bread winner brought home no money on Saturday night. The girls themselves contributed, there was a call for funds throughout the unions and relief visitors were sent out within an hour. The Union offered to bury all unclaimed bodies and during the week following the fire the Relief Committee arranged for 21 burials. Not all of those buried were union members, as the Committee drew no line. Beside the burials immediate relief in the shape of cash payments and medical attendance has been given and rent falling due on the first of the month has been paid. The Union has four classes of cases to consider: First, where families were deprived of all support. Second, where the dependent families are in Europe. Third, where partial support of families has been lost. Fourth, where people were injured and have to be helped until they are well. A compensation act was declared unconstitutional a few days before this fire. The community lays the burden on the workers and safeguards the employers. The Executive Board of the Union has also instructed its attorneys to make such an investigation as will place the blame where it belongs with a view to criminal prosecution.

In one case at least the workers themselves have taken the matter of their safety in hand. In a kimono factory a fire inspector recently found boards nailed over the window leading to the only fire escape. He took them off, warned the employer of the danger and went away. As soon as he was out of the building, however, the employer nailed the boards back again. On Monday morning after the fire the girls in that shop who were members of the Union went to the forelady and said:

“See here, we will not work until the boards are taken off of that window; we are afraid to work unless we know we can get to the fire escape.”

The forelady demurred, it did not seem in her province, but the girls would not go to work.

“We will not go to work and we will call a strike unless the boards are taken down,” they said.

Then the forelady went to the boss. “I’ll see about it,” he said, and the forelady went back and told the girls.

“That won’t do,” said they. “We will not wait for him to see about it, either the boards are taken down immediately or we leave the shop,” and they went to the window, took off the boards with their own hands and sat down at their machines.

The Inspector of the Building Department had failed to help them, all the policemen in New York, the Mayor of the City, or the President himself had not helped them. But the girls by the very simple discovery that if they all stood together they could have what they wanted, had helped themselves.

The same thing has happened in Newark, New Jersey. In the great fire there 25 girls were killed and the Hat Trimmers of Newark realized that they might be burned in the same manner. Being thoroughly organized, a committee was appointed from the Union to visit all the factories and interview the employers in regard to windows which were nailed down being opened, obstructions being removed from staircases and fire escapes put in. Each manufacturer was given a certain time to have things put in order, and the girls said that if at the end of that time nothing was done they would strike. At the end of a month these things which the Building and Factory Inspection Departments had failed to do were accomplished by the Hat Trimmers’ Union.

But of course honorable gentlemen and influential boards have met together in great auditoriums and pled with the people. Said the Governor of the State:

“I want to assure you that my co-operation will be extended with a firm belief that a repetition of the Washington Square disaster will be avoided.”

Said a great banker:

“The conditions which led to the Washington Place disaster should never again be allowed to exist in the city.”

A professor from the University pled for a concentrated fire department so that we would know in future where to place the blame.

Said a Jewish Rabbi:

“We demand industrial peace with security for all.”

But how are these things different from what we heard after the Iroquois Theater fire, the Slocum disaster, the Newark fire? Have not the workers been begged before to preserve a judicial attitude? But you can’t impose a judicial attitude on a mother two of whose children have been burned to death before her eyes. Neither can you on seven hundred and fifty thousand people who think their daughters may be burned to death tomorrow.

Said Peter Brady, of the Allied Printing Trades, in answer to the honorable gentlemen and the influential boards:

“We have very little confidence in your Citizens’ Organization. Not so much as in Capitalistic Greed and Political Neglect.”

And Rose Schneidermann of the Cloth Hat and Cap Makers’ Union put it more definitely still when she said last Sunday in the Metropolitan Opera House:

“This is not the first time men and women have been burned to death. The life of men and women is so cheap, property is so sacred, there are so many of us to every job, that it matters little if 143 die.

“Citizens, you have been tried time and again and found wanting. It would be treachery and treason to those burned bodies if I came here to talk fellowship. Too much blood has been spilled!”

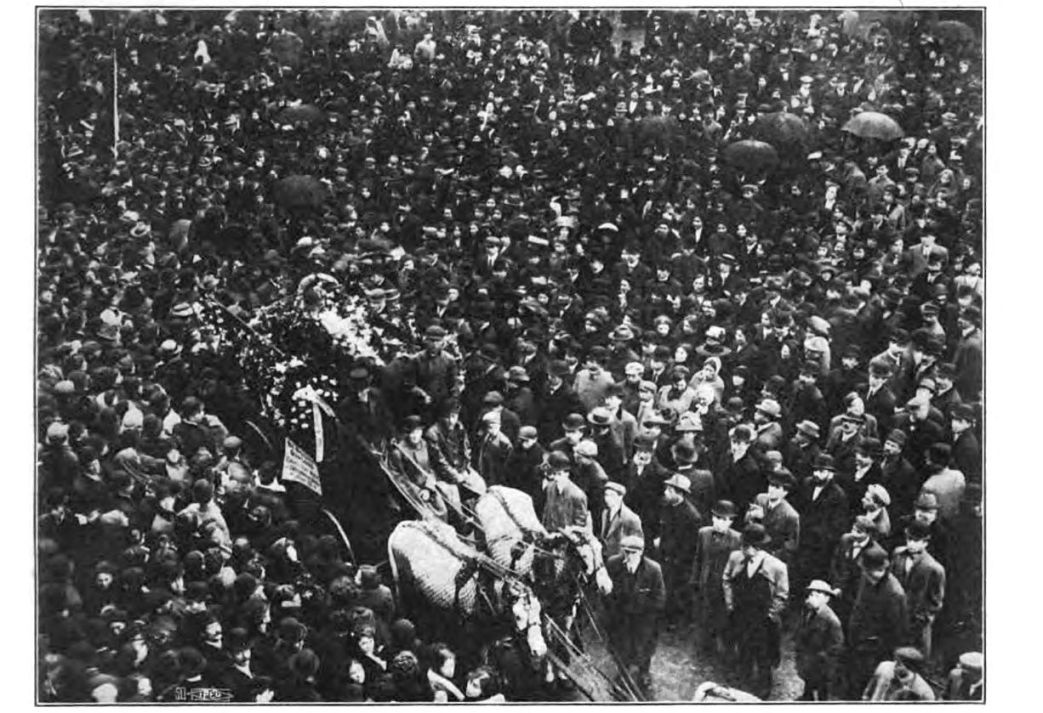

And still as I write the mourning procession moves past in the rain. For two hours they have been going steadily by and the end is not yet in sight. There have been no carriages, no imposing marshals on horseback; just thousands on thousands of working men and women carrying the banners of their trades through the long three mile tramp in the rain. Never have I seen a military pageant or triumphant ovation so impressive; for it is not because one hundred and forty-three workers were killed in the Triangle Shop–not altogether. It is because every year there are fifty thousand working men and women killed in the United States–one hundred and thirty-six a day; almost as many as happened to be killed together on the 25th of March: and because slowly, very slowly, it is dawning on these thousands on thousands that such things do not have to be!

It is four hours later and the last of the procession has just passed.

Life and Labor was the monthly journal of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL). The WTUL was founded by the American Federation of Labor, which it had a contentious relationship with, in 1903. Founded to encourage women to join the A.F. of L. and for the A.F. of L. to take organizing women seriously, along with labor and workplace issues, the WTUL was also instrumental in creating whatever alliance existed between the labor and suffrage movements. Begun near the peak of the WTUL’s influence in 1911, Life and Labor’s first editor was Alice Henry (1857-1943), an Australian-born feminist, journalist, and labor activists who emigrated to the United States in 1906 and became office secretary of the Women’s Trade Union League in Chicago. She later served as the WTUL’s field organizer and director of the education. Henry’s editorship was followed by Stella M. Franklin in 1915, Amy W. Fields in in 1916, and Margaret D. Robins until the closing of the journal in 1921. While never abandoning its early strike support and union organizing, the WTUL increasingly focused on regulation of workplaces and reform of labor law. The League’s close relationship with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America makes ‘Life and Labor’ the essential publication for students of that union, as well as for those interest in labor legislation, garment workers, suffrage, early 20th century immigrant workers, women workers, and many more topics covered and advocated by ‘Life and Labor.’

PDF of issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3859487?urlappend=%3Bseq=151%3Bownerid=9007199256678780-159